On June 2, 2015, the day the Summary Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was released, Liberal Party of Canada leader Justin Trudeau hailed the report as “the truth of what happened [in the Indian Residential School system]”, and vowed that a Liberal government would take “immediate action” to implement every one of the TRC’s recommendations.

While Mr. Trudeau or his advisors could hardly have studied the 94 recommendations and supporting material in the 382-page Report in such short order, they presumably accepted its central assertion that what happened in the residential school system was “cultural genocide”. They are not alone is this belief. Distinguished Canadians such as Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin and former prime minister Paul Martin have publicly endorsed it. Even former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, although he refrained from using the term in his 2008 Parliamentary statement of apology to former IRS students, acknowledged the IRS tried to “kill the Indian in the child”. If it’s true that Canada conspired to do this, surely that is cultural genocide.

It is an indisputable historical fact according to the TRC. Hence its recommendations calling for legal, political, and economic restitution for aboriginal cultural genocide. All are based on the assumption – asserted on the first page of the report – that the schools systematically engaged in “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group” by banning language use, forbidding spiritual practices, and disrupting traditional family life “to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.”

The origin of the cultural genocide allegation is the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RRCAP), which led to the establishment of the TRC, and it has been repeated many times since, though rarely with as much authority as in the TRC Report. But that doesn’t necessarily make it true, and in our view there is little credible empirical evidence to support the charge – let alone the conviction – of cultural genocide.

500 years of shared history

The first government-mandated IRS opened in 1876, or 342 years after Jacques Cartier landed in what is now Canada. As the RRCAP and TRC Report both obliquely acknowledge, this long period of culture contact and colonization saw considerable aboriginal cultural transformation, consisting of both losses and gains: a steady decline in traditional livelihood strategies like subsistence hunting, gathering, and trapping; the abandonment of Palaeolithic technology; the adoption of Christianity; a growing reliance on European trade goods in exchange for the skins of fur-bearing animals and buffalo hides; and a slow but steady demand for and dependence on government assistance as the fur-trade declined and the buffalo were decimated by aboriginals and settlers alike.

Although reliance on aid from the federal government and its related sequalae may be an unfortunate but unintended result of nearly 500 years of culture contact for too many indigenous people, the historical record reveals that aboriginals willingly abandoned many of their traditional beliefs and practices for Western technology, medicine, foodstuffs, religion, and languages from first contact to the present.

A much longer and more consequential period of culture contact preceded the European one. The aboriginal peopling of the New World began over 15,000 years ago and involved one settler group pushing out, assimilating, enslaving, or massacring other settler groups, actions that resulted in the evolution of pristine state societies like the conquest-driven Aztecs of Mexico and the imperialistic Inca of Peru.

Though it did not always lead to the formation of new states, culture-changing tribal and chiefdom warfare were chronic from coast to coast in Canada long before European contact. To be sure, organized fighting between aboriginal Prairie people escalated with the capture and domestication of wild horses originally brought to the New World by the Spaniards. This led to the rise of warrior societies which competed for wealth and prestige gained from stealing horses, killing enemies, and abducting women.

Many of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, such as the Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian, were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders. War captives passed on their bonded status to their offspring. Some tribes in British Columbia continued to segregate and ostracize the descendants of slaves into the 1970s.

The origins of ‘cultural genocide’

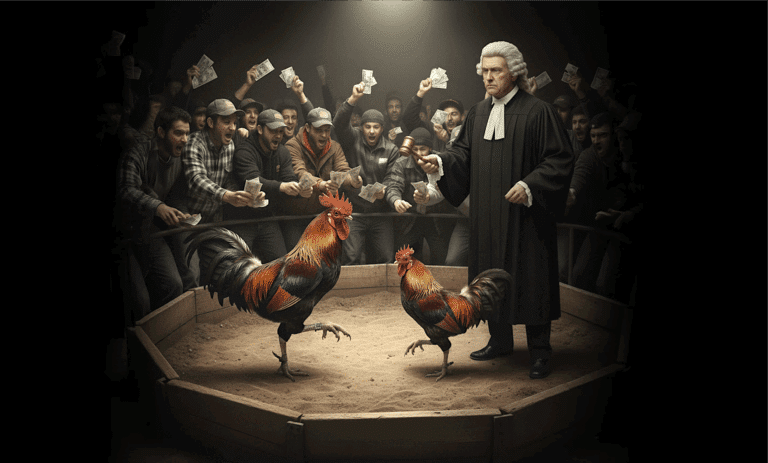

Only in the post-colonial era has the most benign form of conflict-based interaction between alien people – what social scientists have long called acculturation and assimilation – been reinvented as “cultural genocide”. The term was coined in 1944 by Polish-American law professor Raphael Lemkin, who lost dozens of relatives in the Holocaust and later helped the United Nations formulate its legal definitions of actual genocide – the physical extermination of a people.

In recent years the phrase cultural genocide has been used to describe U.S. treatment of its native peoples, Russian treatment of Jews, Israeli treatment of Palestinians, and Communist China’s treatment of Tibetans. With this year’s endorsements by numerous prominent Canadians and the TRC Report, it has achieved widespread currency in Canada: a July Angus Reid poll found that 70 percent of Canadians agreed that cultural genocide described the IRS experience, although most respondents admitted they knew little about the Report or the issue.

To challenge the validity of the nomenclature is not to deny the harsh physical and heinous sexual abuse that sometimes occurred at these often poorly run, maintained, and underfunded schools. These facts are undeniably true, but they do not add up to cultural genocide, partly because the term itself has no legal definition.

Indeed, the concept is so elastic that it could easily be stretched to include the schoolchildren of non-European immigrants to Canada who were required by law to be “Canadianized” in state-mandated public schools whether they or their parents favour this assimilation or not. The label was deliberately excluded from the five grounds listed in the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which says nothing about the loss of culture – the beliefs, values, and ideas that distinguish groups of people from each other; rather, it talks only about the destruction of a “national, ethnical, racial, or religious group” of people using various physical means. Thus it was inaccurate for the TRC to assert that involuntary attendance at residential schools is covered by the Convention.

The Convention does recognize in Article 2(e) that genocide can involve “forcibly transferring children from one group to another group”. This might apply, for example, when Boko Haram jihadists in Nigeria kidnap hundreds of Christian schoolgirls, force them to accept Islam, and marry them off to their fighters. But in our view, this is manifestly not in the same league as Canadian aboriginal children temporarily attending boarding schools to obtain a Western education.

The demand for residential schools

The government-sponsored IRS operated between 1876 and 1996, and mass attendance was in effect only between 1920 and 1948. According to historian J. R. Miller (a strong critic of the IRS), no more than one-third of aboriginal children born during the 120-year history of residential schools actually attended them. Moreover, the compensatory payments issued to residential school alumni via the $1.6 billion Common Experience Payment shows that these students attended for an average of just four years. The TRC Report itself says that truancy rates were “epidemic” at some schools. The record also shows that during the IRS’s last decades, most aboriginal children attended band-controlled day schools or integrated off-reserve public schools.

The cultural genocide charge is further undermined by the fact that the provision of a Western education was often requested by aboriginals and entrenched in six of the seven numbered treaties negotiated in Western Canada. Treaty Six, for example, which extends across the central portions of Alberta and Saskatchewan, was signed in 1876, the same year the IRS were established. At the request of the aboriginal treaty signatories, it promised that, “Her Majesty [Queen Victoria] agrees to maintain schools for instruction in such reserves hereby made as to Her Government of the Dominion of Canada may seem advisable, whenever the Indians of the reserve shall desire it.”

Residential schools were subsequently established on the well-founded and altruistic notion that what remained of aboriginal beliefs and lifestyles in 1876, together with the various social and economic pathologies that were supplanting them, were incompatible with a rapidly developing and modernizing country. The Federal government, along with several Christian denominations, saw their duty as helping indigenous people adapt to this reality.

As is well-documented, Christianity flourished in aboriginal communities across Canada from first contact onwards. Thus, generations of Christian aboriginal parents willingly sent their children to the church-operated residential schools to obtain an education, often alongside European classmates – the sons and daughters of missionaries, Hudson Bay Company personnel, and Indian Affairs employees – another fact the TRC Report chose to ignore. As late as the 1940s and 1950s, when the Indian Act was being amended, many bands and native organizations asked for the schools to remain open. In the 1960s, well after most of IRS had already been closed, several bands lobbied the Department of Indian Affairs to keep some of the remaining schools operating.

The cultural genocide charge is also rooted in weak social science. The legacy of the IRS – “the significant educational, income, health, and social disparities between Aboriginal people and other Canadians,” the negative effects of poor, abusive, or absent parenting, and high incarceration rates – has been found to be no greater among those who attended IRS than those who did not.

In developed countries like Canada, these disparities can be better explained as the product of widespread multi-generational welfare dependency, which social science research has firmly linked to feelings of marginality, helplessness, apathy, fatalism, and a lack of future orientation.

The role of the IRS in trying to mitigate many of these negative consequences is supported in the Report itself which states that during the 1950s and 1960s, up to 50 percent of IRS students were orphans or the offspring of “broken homes.” To us, this looks like an effort by the Federal government and the churches to save both the Indian and the child.

Let multiculturalism reign

Moreover, the cultural genocide thesis ignores the indisputable fact that human beings can assimilate characteristics of two or more cultures, including unrelated languages. The TRC Report implies that cultural learning and retention are zero-sum games, ignoring the abundant evidence of the human capacity for “biculturation.” The truth of this is clearly seen in the diversity of Canadian society, where people from a vast array of cultures have successfully integrated into the multicultural mainstream, while retaining many of their native languages, beliefs, and cultural practices. The TRC Report grudgingly (and perhaps inadvertently) acknowledges that this is as true for aboriginal Canadians as it is for millions of other Canadians when it states that, “Aboriginal cultures and peoples have been badly damaged, [but] they continue to exist. Aboriginal people have refused to surrender their identity.”

This may be the truest statement in the Report, and perhaps the most hopeful one, for it acknowledges that as hard as the IRS may have tried to absorb its students into mainstream culture (i.e., “to kill the Indian in the child”), these efforts failed. The statement also transcends the bitter and hyperbolic narrative of genocide and entitlement, and points to a future where a proud and confident people are recognized – and recognize themselves – as full and equal citizens of Canada, instead of its eternal victims.