Mark Twain is supposed to have said, “Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.” Similarly, it seems nearly everyone in Alberta complains about the federal government’s equalization policy, but no one ever does anything about it. The conventional wisdom is that trying to change equalization would be incredibly difficult if not completely futile – “political science fiction” or an “expensive piece of theatre”. But we can do something about it. When the advocates of equalization got it written into Canada’s constitution in 1982, they didn’t realize their victory also created levers for reform – if we will only lean on them.

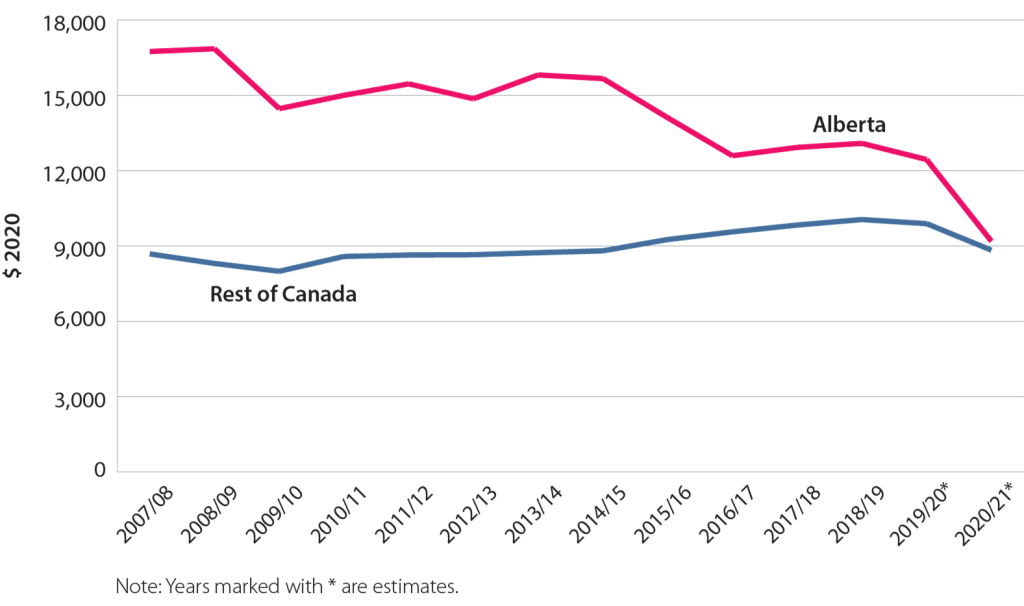

Equalization is headed for a major revision one way or another. Economic events since 2015 have been reducing the differences in fiscal capacity (i.e., taxing power) between Alberta and the rest of Canada almost to insignificance, as shown in Figure 1. This means the rationale for the program is becoming ever-more dubious. Nonetheless – or perhaps consequently – Ottawa will come under intense political pressure from the equalization-receiving provinces to keep the equalization money flowing in their direction. Now is the time for Alberta, which has been uniquely disadvantaged by equalization, to get out in front of the coming revision. It is critical that the province do so.

The alleged purpose of equalization, which began in 1957, was formulated in the 1982 constitutional amendments: “Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.” The concept is that Canada’s poorer provinces shouldn’t be expected to function only by imposing a crushingly high tax burden on their residents. Enforced inter-provincial sharing (routed via the federal treasury) was thus baked into Canada’s overhauled constitution.

All money distributed through equalization comes from general federal revenues – personal and corporate income taxes, GST, and all other taxes, supplemented in most years by borrowing. Ottawa has consulted the provinces from time to time about the formula for distributing revenue, but the federal cabinet makes the final decision. The distribution formula – which grew very complicated over time and today is understood intimately by very few – has been changed many times but is always based on a calculation of “fiscal capacity,” i.e., how much revenue a province can be expected to raise from its own sources.

In fiscal 2020, Ottawa divided equalization payments of $20.3 billion among five provinces: Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Manitoba. Quebec was by far the biggest recipient, receiving $13.3 billion, even though other provinces got more per capita because of their smaller populations. British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Newfoundland have also been recipients at various times.

But not Alberta. This has been the case ever since government revenues from non-renewable resource production (mainly oil and natural gas) were entered into the fiscal capacity equation. This greatly inflated Alberta’s alleged fiscal capacity, even though non-renewable resource production is impermanent and, economists have pointed out, the associated public royalties represent a one-time drawdown of a province’s capital stock rather than taxation of ongoing economic activity.

About 18 percent of federal tax revenue is collected from taxpayers in Alberta, a province with approximately 12 percent of the country’s population. Thus in fiscal 2020, Albertans contributed about $3.7 billion to equalization, of which about $2.4 billion went to the provincial government of Quebec.

We should applaud Quebec for balancing its budget and building up a savings account, as Alberta once did. But la belle province didn’t accomplish this all on its own; Quebec clearly had help. Should Alberta be compelled to transfer so much money to Quebec when its own economy is in disarray?

Given the stated purpose of the equalization program, one would expect that Quebec badly needs the money, and allocates its annual equalization payments towards immediate government services. A little-known fact, however, is that Quebec has been using some of its equalization receipts to build a provincial savings and investment account, its so-called Generations Fund. It now has a book value of about $11.5 billion, as shown in Figure 2.

Within five years – maybe even sooner – the value of the Generations Fund is projected to overtake Alberta’s Heritage Savings Trust Fund, which had a book value of $17.3 billion at year-end 2020. We should applaud Quebec for balancing its budget and building up a savings account, as Alberta once did. But la belle province didn’t accomplish this all on its own; Quebec clearly had help.

Should Alberta be compelled to transfer so much money to Quebec and other provinces at a time when its own economy is in such disarray? The large majority of Albertans would certainly answer a firm “No.” And it is the official policy of the province’s UCP government to seek a better deal on equalization.

The clearest pathway to accomplish this is by taking advantage of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the Quebec Secession Reference . As its name implies, that case in 1998 was primarily about the legalities of a particular province separating from Canada. But on page 69 of its ruling, the Court also went out of its way to discuss constitutional amendment in general:

“The Constitution Act, 1982 gives expression to this principle [democratic discussion], by conferring a right to initiate constitutional change on each participant in Confederation [the provinces]. In our view, the existence of this right imposes a corresponding duty on the participants in Confederation to engage in constitutional discussions in order to acknowledge and address democratic expressions of a desire for change in other provinces. This duty is inherent in the democratic principle which is a fundamental predicate of our system of governance.”

What this means in simple language is that if a province requested that other governments discuss a constitutional amendment, they would be required to come to the table. Despite some public commentary to the contrary, the Supreme Court’s statement is clear-cut, as any reader can see.

Such a request would come through a resolution of the reform-seeking province’s Legislative Assembly. In Alberta, provincial law requires that a proposed constitutional amendment first be approved in a provincial referendum. During the provincial election campaign of 2019, UCP Leader Jason Kenney promised to hold a referendum on equalization “if there’s no major progress on market-opening pipelines.” That referendum would be held on October 18, 2021, in conjunction with municipal elections. At this point, it’s arguable whether such “major” progress has been made; indeed, the state of play regarding oil or natural gas export pipelines is shifting almost from month to month.

In May 2020 the Fair Deal Panel appointed by Premier Kenney recommended that, “If Alberta holds a referendum on abolishing equalization, it should use a very clear and simple question along the lines of: ‘Do you support the removal of Section 36 – establishing the principle of equalization – from the Constitution Act, 1982?’” The Government of Alberta responded in June 2020: “Further work will be done to analyse what an appropriate question would be for an eventual referendum on equalization. This referendum could be held in conjunction with the 2021 municipal elections.”

It would be surprising if such a referendum did not produce a “Yes” vote for constitutional discussions of equalization. Albertans have always known that equalization worked to their disadvantage, but many of us were willing to bear the burden when we were flush with oil and natural gas revenues. Now that times are much tougher, it seems likely that most of us will want to demand a better deal.

Following such a referendum result, the next step would be to obtain a resolution of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta requesting discussions with Ottawa and the other provinces. Other governments might ignore Alberta’s referendum, but they would have to respond to a resolution of the province’s Legislative Assembly.

One can’t predict what might come out of these inter-governmental constitutional discussions. It’s admittedly hard to envision a quick agreement to repeal s. 36, but perhaps consensus could be forged to amend it in a way more favourable to Alberta’s interests. But even if a constitutional consensus could not be reached, these meetings would still create an important opportunity for Alberta to make a political statement about the unfairness of equalization.

For, even without a constitutional amendment, the steady convergence in provincial fiscal capacity means the program will have to be changed through some combination of federal legislation and order-in-council. Alberta can simply no longer afford to be the paymaster of Confederation. By entering the discussions with a well-thought-out agenda for change, Alberta would be better enabled to defend its long-term interests.

There is also another way to do something about equalization: a reference to the Alberta Court of Appeal, asking for a declaratory judgment that equalization as it now exists violates s. 36. It states:

- (1) Without altering the legislative authority of Parliament or of the provincial legislatures, or the rights of any of them with respect to the exercise of their legislative authority, Parliament and the legislatures, together with the government of Canada and the provincial governments, are committed to

- (a) promoting equal opportunities for the well-being of Canadians;

- (b) furthering economic development to reduce disparity in opportunities; and

- (c) providing essential public services of reasonable quality to all Canadians.

(2) Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.

Some legal authorities have argued that s. 36 does not require any particular legislation or indeed any legislation at all because it is a statement of commitment, not a legislative text. Be that as it may, as part of the constitution s. 36 may be used as a criterion for judging the adequacy of existing Canadian legislation and its administrative implementation. The Alberta Court of Appeal, and ultimately the Supreme Court of Canada, could be asked to rule on whether the equalization program, which is based on federal legislation, conforms to the new standards entrenched in the constitution in 1982. The Court could not create a new equalization policy; but, based on many recent precedents, it might order Parliament to pass better legislation, as it has done in other important cases.

The reference strategy is not a brand-new idea. The Saskatchewan government in late 2007 launched a reference case before the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal over the treatment of non-renewable natural resource revenues in the equalization program. The argument was to be that recent federal changes to the program violated s. 36. The case was withdrawn in 2008, however, when the provincial government changed hands.

The key criteria in s. 36 against which equalization can be judged are: furthering economic development, providing equal opportunities, providing essential public services of reasonable quality, and providing reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.

The lack of definitions and criteria in Canada’s equalization policy leads one to conclude that the real purpose of the program in practice is simply to redistribute income from taxpayers in all of Canada to certain favoured provincial governments.

Several features of the current approach to equalization arguably make it unconstitutional. It is supposed to help provinces achieve the goals stated above. But these key terms are not defined in the federal legislation. Without definitions, there are no operational criteria for judging whether services are essential, or of reasonable quality, or reasonably comparable between provinces, or help the various provinces provide equal opportunities to their residents. Thus, there is also no way to know whether equalization is achieving its constitutional purpose. The lack of definitions and criteria also leads one to the conclusion that the real purpose of the program in practice is simply to redistribute income from taxpayers in all of Canada to certain favoured provincial governments.

Equalization has, indeed, been politicized from the beginning because all decisions were put in the hands of Parliament (in practice, the federal cabinet). Making cabinet the locus of decision-making was bound to turn equalization into a political forum for battles over redistribution rather than an impartial, politically neutral program for the adequate funding of essential services throughout the nation. In contrast, Australia has a politically independent Commonwealth Grants Commission to make decisions about that country’s equalization program.

Also contrary to Australia, Canada’s equalization program looks only at provincial fiscal capacity and not at the cost of providing government services. These services, which depend mainly on salaried employees (plus buildings and facilities to house and support them), are usually more costly in metropolitan areas than in smaller cities or rural areas. The highest per-capita equalization payments go to Atlantic Canada, which has no major cities except Halifax.

One should not assume these provinces need a certain level of equalization revenue simply because their fiscal capacity is smaller. They might have lower average expenses that would partially compensate for their lower fiscal capacity. Any fair equalization system should include this criterion so it could be determined whether some provinces could achieve comparable services with lower per-capita equalization payments.

Fiscal capacity was originally defined strictly in terms of provincial tax base. But royalties from non-renewable resources have been included at various times under different formulas. This tends to raise estimates of fiscal capacity for Alberta, thereby ensuring it will be a perennial donor rather than a recipient province. But revenues from renewable resources, above all hydroelectric power, which are permanent and therefore more indicative of a province’s genuine fiscal capacity, have never been treated the same way.

The structuring of Quebec’s electricity-producing sector through Hydro-Québec protects large amounts of revenue from being counted in that province’s fiscal capacity. As a Crown corporation, Hydro-Québec does not pay taxes, and it is able to reduce costs for Quebec individuals and corporations by manipulating electricity rates. Thus, Quebec is made to look poorer than it really is. This treatment of renewable resources is no accident; it stems from the political pressure that Quebec has been able to exert.

Badly designed government programs always lead to unintended and undesired consequences because of the incentives they create. For one thing, equalization creates bizarre incentives for provinces to raise tax rates because doing so lowers their incremental fiscal capacity as defined in the program, thereby entitling them to larger transfers. Higher taxes contravene the goal of “reasonably comparable levels of taxation” and they work against the goal of “furthering economic development” because higher taxes depress economic activity. It is a truism of economics that the more you tax something, the less you get of it.

Recipient provinces also tend to avoid the development of non-renewable natural resources because the royalties would raise their fiscal capacity, thereby reducing the size of their equalization transfers. Recent examples from the oil and natural gas industry include the prohibitions on hydraulic fracturing and production in Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. When provinces do promote the development of non-renewable natural resources, as Newfoundland has done, they get into vicious fights with Ottawa over the equalization program’s clawback provisions.

By contrast, recipient provinces have incentives to engage in the development of renewable natural resources, which does not increase their recognized fiscal capacity. This has included Quebec at all times and Newfoundland recently, with its disastrous Muskrat Falls project, which has been termed the “biggest economic mistake” in the province’s history. This distortion of economic incentives interferes with the s. 36 goals of “furthering economic development” and “promoting equal opportunities.”

Public sectors in recipient provinces tend to swell in scale, exceeding those of donor provinces. The combination of higher tax rates and equalization payments funds more and larger government programs. Research by economists has established that, from the point of view of fostering economic growth, the optimum size of the public sector is about 25 percent of gross domestic product.

All Canadian jurisdictions are well above that level, and the recipient provinces are the furthest above it. Not surprisingly, their economic growth is chronically sluggish. Thus, the hypertrophy of the public sector works against the goal of “furthering economic development.” (The current converging of fiscal capacities among provinces is due to the decline of the oil and natural gas industry in Alberta and Saskatchewan, not to any burst of growth in the recipient provinces.)

Paradoxically, recipient provinces often have a higher level of public services than donor provinces. The examples of cheap daycare and university tuition in Quebec, as well as the proliferation of universities in the Maritime provinces, are well known. But it is not just a matter of anecdotal evidence. Over a wide range of indicators in the field of education, recipient provinces commonly enjoy a higher standard of provision than donor provinces. These results put the lie to the goal of “reasonably comparable levels of public services.”

Even as equalization is becoming more expensive, the gaps in fiscal capacity among the provinces are declining, leading to the paradoxical outcome that more money must be spent on equalization even as the program’s original justification – differential provincial fiscal capacity – is diminishing.

In 2009, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper introduced the “GDP growth rate rule” to set an upper bound to the year-over-year increase in the total sum of equalization payments. But because of subsequent changes in the fiscal capacity of various provinces, payments soon burst through the intended ceiling, which has now become a floor, causing equalization to be more expensive than it otherwise would be. Moreover, even as equalization is becoming more expensive, the gaps in fiscal capacity among the provinces are declining, leading to the paradoxical outcome that more money must be spent on equalization even as the program’s original justification – differential provincial fiscal capacity – is diminishing.

There is an even more perverse consequence for Alberta and Saskatchewan: the fiscal capacity of these two provinces, and only these two provinces, has declined since 2015. Yet, because they receive no benefit from equalization while the program’s total cost keeps growing, they have to pay ever more to support recipient provinces whose relative fiscal capacity has been increasing.

This combination of obvious design flaws and highly damaging unintended consequences can be used by Alberta – plus any other equalization-paying provinces that wish to join in – to mount a persuasive argument that equalization in practice does not live up to the goals enunciated in s. 36 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and is therefore unconstitutional. Whether by constitutional discussions or by action in the courts, or perhaps by both, it is time to tackle equalization to make it work better for Alberta and all of Canada.

Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary and a former campaign manager for conservative political parties.