As a student at university, I participated in many informal discussions and ad-hoc weekend seminars with my classmates, brilliant young men who were fascinated by the language and theory of Marxist political philosophy. We were, of course, amateur souls, caught up in a state of parvenu ostentation and captivated by ideas. I had some trouble keeping up with them for they were a precocious group, convinced that they were the future architects of an ideal world in which all social and economic inequalities would be erased. They spent semester-hours poring over the most obscure and incendiary writings of their intellectual heroes: “Gracchus” Babeuf, Rousseau, Hegel, Marx, Engels, Althusser, Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse and a host of others.

One student had produced a map of Hegel’s tenebrous Phenomenology of Spirit, which resembled a topographical sketch by an early explorer of the New World wilderness. He was fond of quoting and explicating Hegel’s maxim from the Phenomenology: “Absolute substance is the unity of the different self-related and self-existent self-consciousnesses in the perfect freedom and independence of their opposition as component elements of that substance: Ego that is ‘we,’ a plurality of Egos, and ‘we’ that is a single Ego.” Translation: the unity of a redeemed humanity was assured. Only later did I think to ask whether Hegel had actual evidence that any of this might unfold.

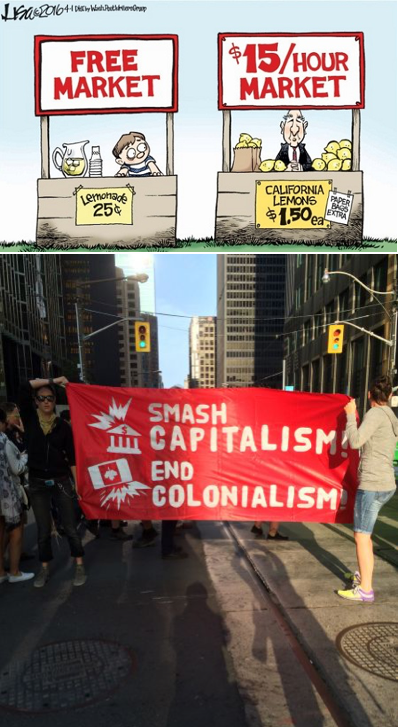

Another came equipped with a Monopoly set to illustrate the capitalist exploitation of property relations and rent management, showing how Boardwalk and Park Place would inevitably swallow Mediterranean Avenue and Baltic Avenue, and how monopolists control railroads and utilities while avoiding Income Tax Space and Luxury Tax Space, all to the detriment of the poor. Obviously he’d never met my friend who routinely won Monopoly by starting with small amounts of cash invested in the cheapest properties.

Another argued that Immanuel Kant’s three ground-breaking Critiques served as a precursor to Marxist doctrine, cooperative socialism, peaceful harmony as an ultimate historical resolution of competitive interests, and as a warning against capitalist individualism. Kant, he said, proposed “an inner instantiation of the realm of ends,” a phrase I never forgot and which I later discovered he had pilfered from Hermann Cohen. Still another was at pains to justify Herbert Marcuse’s oxymoronic program of “repressive tolerance” wherein freedom depends upon repressing others, particularly conservatives and free marketers, and which applied to anyone outside our little group who insisted on the rights of the sovereign individual and private enterprise.

My classmates all denounced the greed, oppressiveness and “cash nexus” of the capitalist profiteer and all were supported by their prosperous parents, who paid their tuition fees and provided them with every comfort of life, including lodging, pocket money, cars and the books they treasured. The luxury of theory trumped the grit of reality. In later years, they ceased preaching communist doctrine and joined the upper middle class, becoming teachers, lawyers, media moguls and businessmen – apart from one who became a union executive and professional agitator after inheriting a fortune, akin to Anderson Cooper at CNN. We might say they received an exemption from fate, or eventually came to their right minds.

But considering our culture’s plethora of leftist thinkers, fellow travellers and public intellectuals, my juvenile comrades were exceptions to the rule. For leftist intellectuals are an evolving phylum in the West that has broken out of its core academic habitat and is everywhere to be found, in politics, in technoland, in journalism, in the digital media and even among the anointed class.

The question asks itself: Why are so many intellectuals adherents of the left? How can so many presumably brainy people, university graduates with alphabets trailing after their names, writers with style and erudition, or professional historians with faculty sinecures, regard themselves as Marxists, socialists, progressivists, Wokesters, consumed by phalansterian passions? How can the favoured individual credibly lobby for the featureless collective, a posture if not unethical then plainly inconsistent?

The question I’m broaching pertains to ‘intellectuals’ qualified by scare quotes, and principally to people smart enough to know better who have worshipped and continue to sacrifice at the altar of ‘the god that failed.’

There are disparate modalities, of course. The rubric “intellectual” covers many categories of thought and sentiment and many gradients of quality, both left and right. There are the “greats,” the provocative originals like those mentioned above who established the lexicon and consolidated the patterns of political, economic and philosophic thought that gave us the cavalry of the left – the lesser writers as well as people like my classmates, able through their station in life to do more than mere foot-soldiers. Many such leftists are merely epigones and discursive mediocrities, party hacks and minor hangers-on – intellectuals in name only, colporteurs of the trade.

Others, like Noam Chomsky, Terry Eagleton, Christopher Hitchens and Eric Hobsbawm, to cite only a few iridescent figures, are influential but secondary lights in the leftist pantheon, however prominent. And many brilliant intellectuals (to use the term in its original designation) such as Alain Finkielkraut, Joshua Muravchik, Richard Ellis, Gertrude Himmelfarb and Dinesh D’Souza, to name just five prominent thinkers on the right, are eloquent critics of so monumentally failed and destructive an ideology.

There is obviously more than one cause for so glaring a mental dereliction as socialism or communism: the “red diaper” syndrome (being born to committed leftists); the suffering at the hands of fascist dictators (Cf. the Frankfurt School that fled Nazi Germany); distressing experience in the competitive milieu of free-market capitalism; simple complacence; the temptation of belonging to a crowd of one’s peers; being in the vanguard of remaking the world; and so on. The question I’m broaching, however, pertains to “intellectuals” qualified by scare quotes, and principally to people smart enough to know better who have worshipped and continue to sacrifice at the altar of “the god that failed.”

I have long thought about this paradox, at least since reading Julien Benda’s La trahison des clercs (The Treason of the Intellectuals), which laments the politicization and self-indulgent crassness of intellectual life in Benda’s time. What he says of morality, that its “criterion resides in disinterestedness” (i.e., that it must be accepted as objective or it is both selfish and useless), is equally true for him of honest scholarship and intelligent commentary, attributes lacking in the “clerics” of his day. Paul Johnson’s Intellectuals and Thomas Sowell’s Intellectuals and Society are valuable elaborations of Benda’s argument concerning the pride, fallibility and bad faith of the breed. I now believe that the solution to the enigma is not as perplexing as it first appeared.

The mind is potentially omniphagous or magpie-like, prone to devouring many strange and inedible things. This is certainly true of the major thinkers of the left endowed with the free-floating mental energy of a mind working overtime, always whirring and darting this way and that, but devoid of practical good sense.

A mind of a certain idealistic and unregulated stamp may not be satisfied with customary fare, obvious realities and common-sense insights. It seeks complexities, theoretical intricacies. It is addicted to labyrinthine speculations. It cannot believe that the answers to major social questions are readily forthcoming or, with patient effort and sensible application, may be discernible. It does not acknowledge limits or the margins of possibility in the radical project of restructuring humanity and reinventing society from the ground up. In a nutshell, it lacks humility.

Minds of this nature will find conservative studies of social and cultural phenomena undistinguished and boring. Where is the cerebral excitation they relish, say, in the works of Hegel or Marx or Lukács to be found in the judicious productions of Burke or de Tocqueville or Scruton? There are anomalies. For example, writing in Current Affairs, author Nathan J. Robinson, whose books include Why You Should Be A Socialist and Responding to the Right and who describes himself as a “libertarian socialist,” admits: “Personally I spend more time reading conservatives these days than reading leftists, because I am trying to understand how their arguments work and why their rhetoric is persuasive.”

The essay in question, however, Literature of the Left, reads like a love letter to the library of the larboard. “The political left,” Robinson tells us, “has produced countless classic works of analysis, memoir, and fiction,” and proceeds to lavish unstinting praise on as many as he can. His thesis does not strike me as particularly cogent. Minds without pragmatic heft or common sense, without modesty regarding facts, cannot survive minus the adulation of uncritical scholiasts and certainly without the solace and nutriment of theory. As Hannah Arendt said in The Last Interview about German intellectuals when Hitler came to power: “I still think that it belongs to the essence of being intellectual that one fabricates ideas about everything….Today I would say that they were trapped by their own ideas.”

The leftist mind tends to be fixated on the teasing multiplexity of wiredrawn hypotheses and dialectical hijinks – tchotchkes, as my Russian grandma would say – that issue in a utopian terminus that never was and never can be. For the leftist theoretician, the world does not exist wholly in its own right.

In this way, “intellectuals” differ from conservative thinkers and writers who tend to be preoccupied with the world as object rather than the world as alibi, that is, as material for the egocentric and unmediated intellect. Hegel again, from System of Ethical Life and First Philosophy of Spirit, a volume that is almost unreadable: “Knowledge of the Idea of the absolute ethical order depends entirely on the establishment of perfect adequacy between intuition and concept, because the Idea itself is the identity of the two.” In other words, the ethic of the high left, such as it is, has to do with fidelity to the concept rather than, as Benda believed, with disinterested and sober inquiry into the thing itself.

Of course, conservative minds are no strangers to conceptual athleticism and vigorous thinking, as any acquaintance with F. A. Hayek or Richard Weaver, to take just two illustrations of exacting but accessible conservative writers, can attest. But the difference is cavernous. According to Julius Evola in his opulent Men Among The Ruins, a traditionalist manifesto, leftists are not intellectuals in the authentic meaning of the word – that is, as impartial thinkers, minds rooted in transitives rather than absolutes, in things as they might be rather than in things as they must be – any more than genuine conservatives are “reactionaries” in the negative implication the word has acquired. The genuine conservative is not, as leftists claim, a defender of “a particular economic class.” For conservative minds are essentially grounded in the facts of human nature, the history of the feasible and the wisdom of tradition.

“Conservative spirit,” Evola writes, “and traditional spirit are one and the same thing.” They form the very crux of humanism. The leftist mind, on the other hand, tends to be fixated on the teasing multiplexity of wiredrawn hypotheses and dialectical hijinks – tchotchkes, as my Russian grandma who fled the Soviets would say – that issue in a utopian terminus that never was and never can be. For the leftist theoretician, the world does not exist wholly in its own right. It is to a great extent an excuse for untrammelled speculation and experimentation (the lessons of which are never, alas, learned).

Perhaps this is why the term “intellectuals” has acquired its pejorative sense. It signifies a species of mind divorced from common experience and committed to cerebral excess and unsponsored reverie in the absence of demotic foundations and plain reason. For all its differential subtlety and sometimes neural glitter, it is bound to get things wrong. As Sowell writes in Intellectuals and Society, “Karl Marx’s Capital was a classic example of an intellectually masterful elaboration of a fundamental misconception.” And as Johnson warns, “Intellectuals create climates of opinion and prevailing orthodoxies” which for all their allure can generate “destructive courses of action.”

Intellectuals, as Johnson and Sowell deploy the word, habitually forget that “people matter more than concepts.” One thinks of Hegel’s brocard from the Preface to the Phenomenology: “Everything depends on grasping and expressing the ultimate truth not as Substance but as Subject.”Clearly, for Sowell and Johnson, intellectuals are men and women of the left, more concerned with “subject” than with “substance.”

Broadly speaking, then, the leftist mind is in love primarily with its own operations; the humanist mind focuses on the world of real people as they are. The first in its quest for reasons will add another layer of fugitive supposition to the surface of its manipulations; the second sees what reasonable changes are possible in the actual world. For the first, the world is a pretext to sustain its own unmoored redactions, however inventive; for the second, the world is the text itself, to be read and faithfully understood.

The Spider and the Bee

The antithesis between left and right, “intellectual” and humanist, speculator and classicist, rationalist and conservative, is probably perennial. Benda, for example, contrasts the power-mad sophist Callicles in Plato’s Gorgias with Socrates as seeker of truth. It’s an old distinction, sometimes expressed as a literary trope that goes back principally to Plato’s Ion and Horace’s Odes (IV, 2), predicated on the difference between the spider and the bee, the repugnant and the admirable.

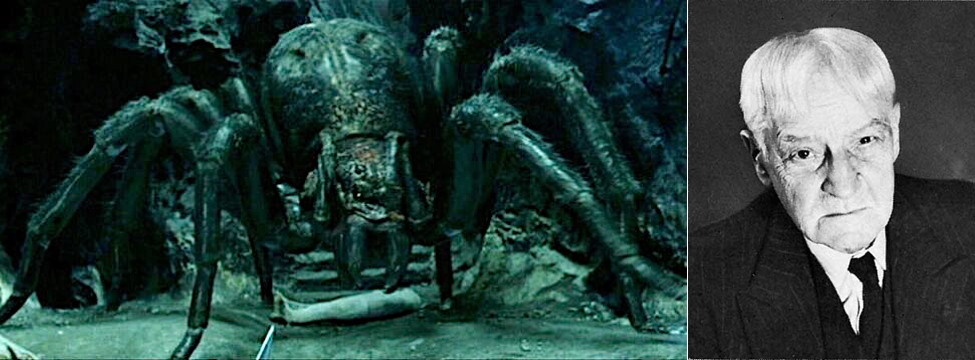

For centuries the spider has stood in allegorically for the egocentric intellectual theoretician in literature and poetry, often set in opposition to the busy and benignly productive bee, which makes its sweet honey available to all. Depicted at left, the fearsome Shelob from the movie version of Lord of the Rings. French philosopher and novelist Julian Benda (at right) argued that the antagonism between the intellectual and the humanist – the spider and the bee – is perennial.

The motif, of course, is not really fair to the spider, a fascinating creature with its own unique and exquisite emanations, but it is a convenient target for revulsion as opposed to the beneficent bee. (The horror inspired by Shelob the giant spider in the film version of Lord of the Rings is an illustration of this primal reaction.) In any event, the bee has stood metonymically for the faculties of imagination, inspired wisdom, diligent work and magnanimity since its earliest appearance in the mythological record. The bee had been gathering pollen in the philosophical and humanist garden long enough to turn him into a reputable Ancient himself, a prototype of the conservative disposition.

The notion is fully developed in Jonathan Swift’s magisterial The Battle of The Books, in which he pits the bee against the spider, the “Ancient” (conservative) against the “Modern” (rationalist). Swift contrasts the spider “drawing and spinning out all from itself” – an involuted mode in which technique becomes its own ultimate datum – to the “sweetly foraging bee” which secretes honey and wax as a gift to mankind. One thinks, too, of Swift’s precursor Francis Bacon who in his Apothegms New and Old wrote that, “The Rationalists are like to spiders; they spin all out of their own bowels. But the bee…hath a middle faculty, gathering from abroad, but digesting that which is gathered by his own virtue.”

Swift’s use of the bee figure soon became part of the melitic tradition and was taken up a century later by that belated Ancient and stalwart conservative Matthew Arnold in Culture and Anarchy where “sweetness and light,” the honey of useful knowledge, are made the definitive qualities of cultural perfection, “a perfection in which the characters of beauty and intelligence are both present.”

The symbol has cultural warrant in the social and political dimensions, distinguishing two basic types of intellectual affinity. The conservative, the traditionalist, the humanist testifies to the importance of historical continuity, the custodial preservation of the best the past has to offer, and apian curiosity coupled with humility before the canvas of human experience, represented allegorically by the image of the bee. The conservative tends to work a lot harder, too, and in foraging and building to look after his own needs, delivers to humankind the products, edifices and inventions that advance civilization. The rationalist, the lover of baroque distinctions and abstruse conjectures, the purveyor of conceptual excesses, is like the metaphorical spider which feeds on ephemerae and engenders on itself, diminished precisely by its strident and arachnoid egoism.

In brief, conservatives are committed to intelligence, leftists to intellect, the right to judgment, the left to theory. One recalls the old philosophical joke about a Continental rationalist replying to the practical argument of a British empiricist, saying: ‘Very interesting, but does it work in theory?’

On the philosophical plane, it’s a converse summed up in the figure of empirical thinker John Locke, who restricted the mental apparatus to the perception and ordering of particulars available to the senses as a prerequisite for judgment. The contrary predisposal is represented by the rationalist thinker René Descartes, who stressed the intuitive infallibility of the singular mind. Descartes with his reticulated vortices, his locating of the soul in the pineal gland and his cruel indifference to the suffering of animals whom he considered automata, was a particular bogeyof Swift’s, who castigated the rationalist philosopher as a chief exemplar of the modern lunatic fringe. In contemporary political terms, Locke would have voted right. Descartes would have voted left.

As Locke understood, judgment is of the essence, the faculty that examines the social and political realm in its actual constitution, with an emphasis on what it permits within its constraints and with a view to its gradual improvement. This is the basis of sound conservative thought. Mere speculative assumptions imposed by desire and “unhinged” intellectual constructions would produce only fantasies doomed to dissolute irrelevance and social mayhem. In Liberating Judgment, a compelling study of Locke’s political philosophy, Douglas John Casson shows how the debasement or circumventing of intelligent judgment of practical affairs leads to cognitive dereliction, disorder and conflict. It is also a harbinger of economic collapse, a form of “coin clipping,” a major scandal of Locke’s era.

With respect to judgment, Sowell’s formulation is analogous and merits consideration. He discriminates between intellect and intelligence: “Intelligence minus judgment equals intellect.” Smarts without judgment gives us the “intellectual,” the leftist intelligentsia, mind not solidly anchored in reality, a cobwebby instrument which Swift described, for all its occasional grandiosity, as “a lazy contemplation of four inches round,” disconnected from both the human and natural world.

In The Problem With Socialism, Thomas DiLorenzo vividly points out that socialism produces “environmental nightmares,” despoiling the natural world in ways that even raw, unregulated capitalism could not envisage. Regarding the Soviet Union, for example, “Between 1920 and 1960, the Black Sea coastline shrank by half…and the Aral Sea [became] a salt marsh.” The Caspian Sea was also devastated. “The concentration of oil in the Volga River was so great [that passengers were forbidden] to toss cigarettes overboard for fear that the river might catch fire,” DiLorenzo writes. It is also common knowledge that sunken and scuttled Russian subs are leaking radiation into the Baltic Sea. The natural world fares no better in China, which “has followed Russia down a path of environmental destruction.” Venezuela is an unmitigated disaster. As for the human world, the casualty count in deaths and suffering in these countries does not bear considering.

In brief, conservatives are committed to intelligence, leftists to intellect, the right to judgment, the left to theory. One recalls the old philosophical joke about a Continental rationalist replying to the practical argument of a British empiricist, saying: “Very interesting, but does it work in theory?” The bee and the spider are continually at war in the cultural arena they inhabit, the one productive in the world, the other spinning round its own centre, putting Descartes before the horse. In a sense, we are witnessing a battle of the books between those who champion the practical value of work and those who argue the labour theory of value. Admittedly, these are sweeping generalizations, but however we account for them, the differences are palpable.

David Solway’s most recent volume of poetry, The Herb Garden, appeared in 2018 with Guernica Editions. His manifesto, Reflections on Music, Poetry & Politics, was released by Shomron Press in 2016. He has produced two CDs of original songs: Blood Guitar and Other Tales (2014) and Partial to Cain (2019) on which he is accompanied by his pianist wife Janice Fiamengo. His latest book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London.