The 21st century is often described as a time of uncertainty, upheaval, chaos and doom. Elites even have a term for the interlocking problems they think we face. They call it “polycrisis” – a word coined in the 1990s by French sociologist Edgar Morin. That word has become notorious in recent years thanks to overuse by the former Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab, and his fellow Davos Men. There’s no question the world has problems, but terminology and jargon often do more to obscure reality than to illuminate it. The “polycrisis” people don’t seem to know that human life has always been beset by war, disease, disaster and an ever-changing climate. Those problems have not become so unique and multifaceted that we need new terminology to describe them.

But there is one problem that seems entirely new. This is a decline in fertility nearly everywhere in the world over the past century. Practically speaking, this means an ever-larger proportion of seniors until a given population begins to shrink as deaths outpace births. If a population is to hold steady, births must slightly surpass deaths, and so the fertility rate must be about 2.1 children for each woman – the so-called “replacement” fertility rate. If the population is to grow, it must surpass that rate so that births significantly outpace deaths for years.

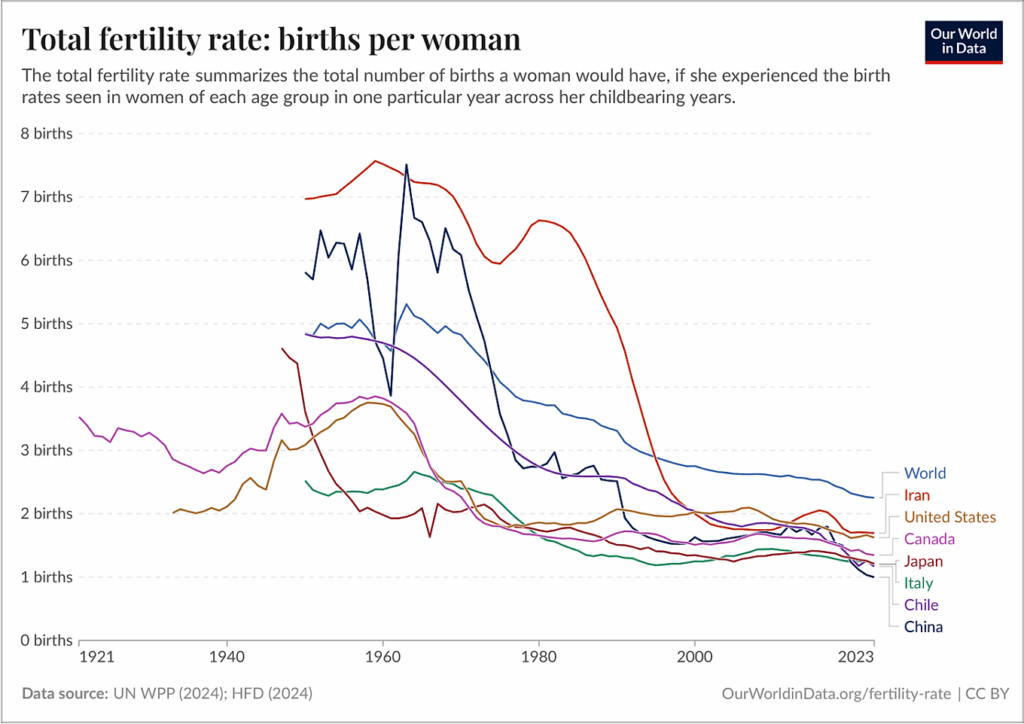

This is now the case in fewer and fewer places. Even replacement-level fertility is increasingly rare. Birth rates have sagged or plunged not only in relatively well-known cases like Italy, which went from 3.3 births per woman in 1920 to 1.24 a century later, or Japan (5.2 in 1920; 1.33 in 2020), both of which became developed and largely secular countries during this period, but in less-developed and until recently devout countries such as Chile (which has plunged from 5.9 births per woman to 1.54 over that century) and Iran (from 7 in 1920 – and still well over 6 in the mid-80s – to a below-replacement 1.71 in 2020).

A recent study in The Lancet expects that by 2100, 97 percent of countries will be shrinking. Only Western and Eastern sub-Saharan Africa will have birth rates above replacement levels, though births will be falling in those regions also. In the industrialized West, births have fallen further in some places than in others, but all countries are now below replacement levels (except Israel, which was at 2.9 in 2020), while populations that continue to grow do so mostly if not entirely because of immigration. Deaths have long been outpacing births in China, Japan and some Western countries like Italy.

Demographers have accordingly begun to speak of “peak humanity” and “peak child”: a looming maximum from which the human population will begin to decline – and rapidly. Impending population decline is not mere theory or exaggerated prognostication: humanity has already passed a moment, believed to have occurred sometime in 2022, when the number of children in the world below 5 years old stopped growing.

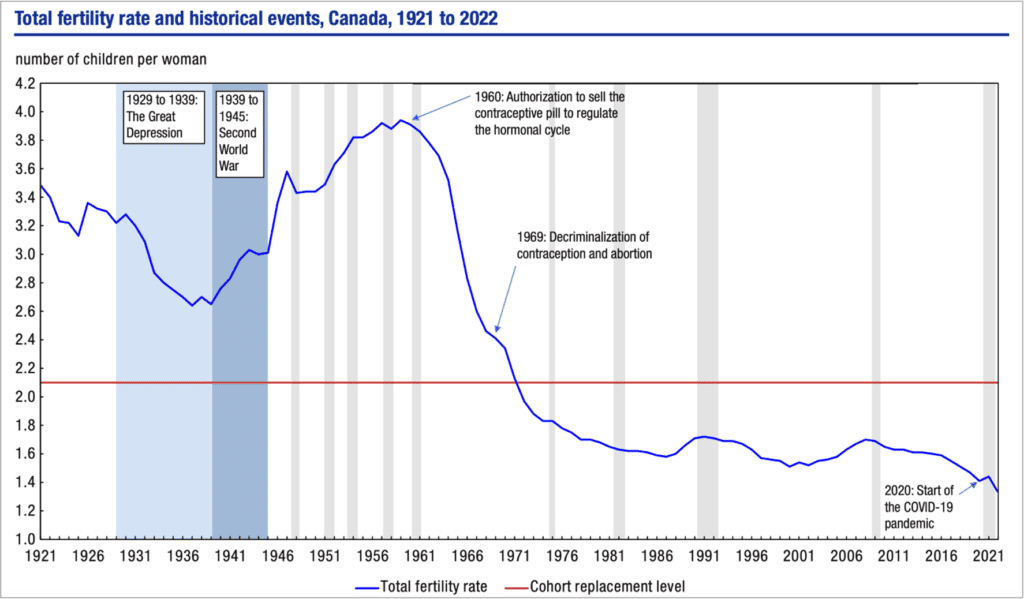

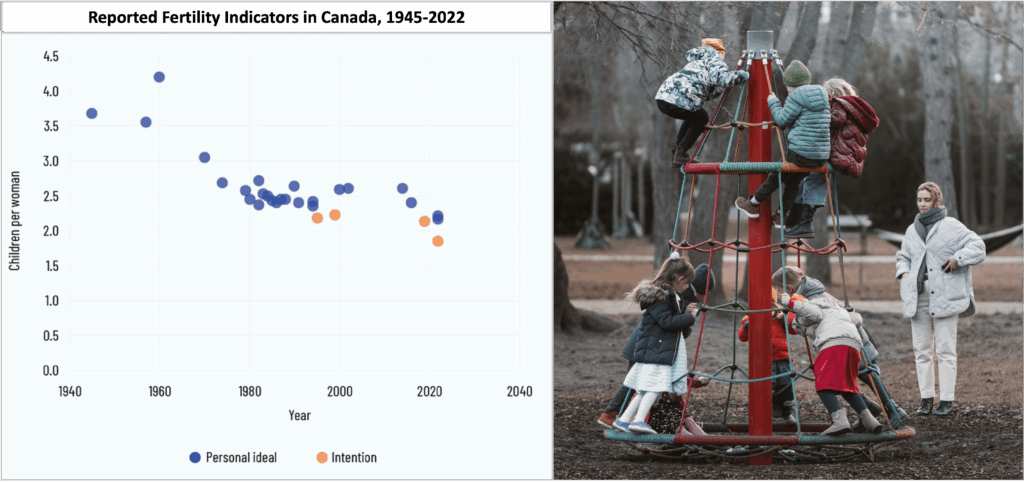

Canada is no exception to this trend. Our fertility rate peaked in 1959 at 3.94 children per woman and reached an historic low of 1.26 in 2023. Today it seems astounding even to contemplate that, within living memory for millions of Canadians, the average Canadian woman delivered nearly four children. Today our fertility rate is not only below replacement but below the most recent OECD average of 1.5, and all signs point to further decline.

It seems to me that falling fertility is a problem that Canada, Western countries and the world at large have simply failed to solve. Instead, we papered over it, so to speak, over the course of the later 20th century, and delayed without avoiding an inevitable reckoning. I shall explain why I believe this is a problem; but first I want to address the opposite perspective since it has been dominant for a long time.

The Malthusian Misfire

Many continue to argue that falling fertility is not only not a problem but also a much-needed corrective. In their minds, overpopulation is the problem. They believe that the same quantity of resources available as before, shared among a smaller population, would mean a more prosperous and richer society. Something like this is advocated by the Population Institute Canada, a think-tank based in Ottawa. It favours lowering the world’s population to a level “enabling decent living standards for all and environmental sustainability at home and abroad.”

Malthus seemed to regard the world’s resources as an essentially fixed stock, like a large but nonetheless limited pie; as ever-more mouths crowded around the table, the slice available to each individual guest could only shrink. He also seemed to think humans had no real ability to solve problems or improve their material well-being.

The institute recommends that Canada’s population “be stabilized to sustainable levels” and “should be balanced between birth & death rates, immigration & emigration, and that couples be encouraged to have small families.” (Given Canada’s current birth rate, the term “small” family would seem to imply no children at all.) That is a seemingly well-intentioned outlook. It is, nevertheless, wrong, and it is important to explain why it is wrong if we are to grasp the nature of the problem before us.

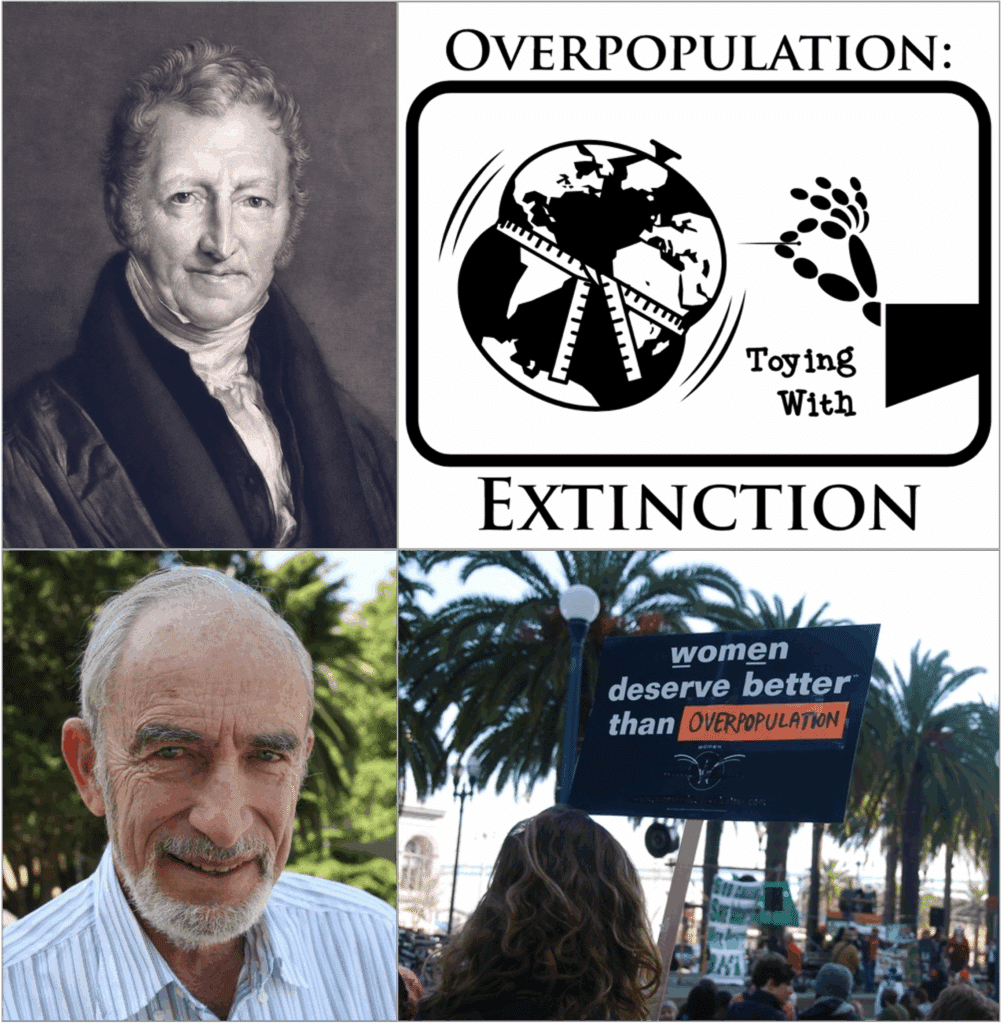

This point of view is essentially a by-product of several old, interconnected errors and false assumptions which, for some reason, refuse to die. The mistakes famously began with English clergyman and political economist Thomas Robert Malthus. His 1798 book An Essay on the Principle of Population warned that “the power of population” was “so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race.”

Malthus seemed to regard the world’s resources as an essentially fixed stock, like a large but nonetheless limited pie; as ever-more mouths crowded around the table, the slice available to each individual guest could only shrink. He also seemed to think humans had no real ability to solve problems or improve their material well-being – and this despite Malthus living in the midst of the Enlightenment and on the very cusp of the Industrial Revolution.

In our own time, many have pursued the same mode of thought, and American biologist Paul Ehrlich is the most notorious of them. His 1968 book The Population Bomb predicted the imminent and inevitable starvation of hundreds of millions of people in the 1970s. Nothing persuaded him to change his mind. Even four decades after the bomb had failed to go off, Ehrlich was still insisting there was only a 10 percent chance of avoiding the total collapse of human civilization on account of famine.

And while the destruction of humanity kept failing to occur, the destruction caused by Malthus and his followers has proved enormous, because their thinking triggered or influenced a vast number of wrongheaded, damaging and outright evil policies.

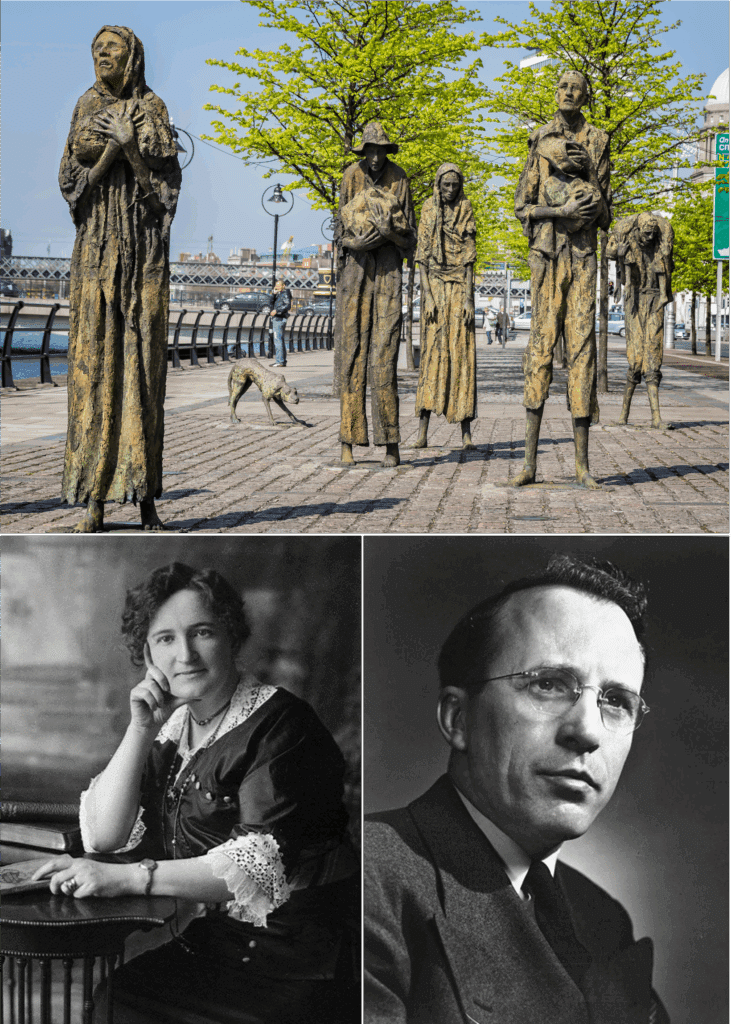

To take just a few examples, Malthusianism was the pretext for diminishing food doles to the poor in 19th-century England, so as to stop them from reproducing. It was the justification for letting the Irish Potato Famine kill off what was deemed the “surplus” population. Forcible sterilization of “imbeciles”, alcoholics and others in the early 20th century found their impetus with Malthus also. Long-revered Canadian suffragette and MLA Nellie McClung notably implemented such a eugenicist policy in Alberta. Tommy Douglas, founder of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation that later became the NDP, advocated sterilizing and segregating people of “sub-normal” intelligence in order to prevent them from reproducing and wasting scarce resources. He advocated this in his 1933 Master’s thesis The Problem of the Subnormal Family, a view which he seems later to have abandoned, albeit without any explicit, public repudiation.

Finally and most horribly, the Nazi obsession with expansion into Eastern Europe and the extermination of its inhabitants appeared to have a pseudo-scientific justification in a fear of scarcity and unchecked population growth. Hitler ominously declared this in Mein Kampf. To paraphrase libertarian economist Bryan Caplan, Malthus told Hitler how many millions should die, and eugenics told him who should die. The awful association with the Nazis was enough to discredit eugenics, thankfully – but not Malthus for some reason.

So, to repeat: Malthus was wrong. Nothing like his predictions has ever come true. The pie turned out not to be fixed in size; it grew – dramatically. Ehrlich has also repeatedly been proven wrong. The story of the second half of the 20th century is in fact one of diminishing poverty and rising prosperity – alongside astonishing growth in global population from only 1.6 billion at the dawn of the century to 6.2 billion at the close of the millennium. The world of the mid-20th century had about 2.5 billion people in it, and it was much poorer than we all are now. Arable land is no longer the primary source of wealth, but we are now able to farm more efficiently and more productively than ever before. As populations have risen, so have the resources needed to feed them and so has the general level of prosperity. And it was all thanks to human ingenuity and commerce. More human beings accordingly mean more resources available, not fewer.

But for all that, a paradoxical thing has occurred in recent decades. Human fertility is now highest where food is least plentiful, and – contrary to Malthusian expectation – the best-fed countries in the world now have the fewest babies. For this reason alone, falling fertility and shrinking populations should be cause for alarm. In my opinion – and the evidence suggests I’m right about this – not only is a small population not “necessary” for prosperity, it is actually the enemy of prosperity. Today, it is not hard to foresee Western societies getting older, smaller and sclerotic, sinking back into poverty and increasingly petty politics. And, in many places, it seems that this regression is already well advanced.

The Real Demographic Time-Bomb – And its Fake Solution

Here in Canada, I can illustrate the problem with a single example at the centre of our self-image. In the 1960s Canada embraced the principles and practice of the welfare state – a multi-billion-dollar system of government programs that transfer money and services to Canadians in order to address various needs or demands. This was the origin of a host of federal, provincial and municipal programs including social assistance (welfare), the Canada Child Tax Benefit, Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, Unemployment Insurance, the Canada and Quebec pension plans, Workmen’s Compensation, social housing, heavily subsidized and ever-more widely available post-secondary education, myriad other social services, and publicly-funded provincial health insurance plans.

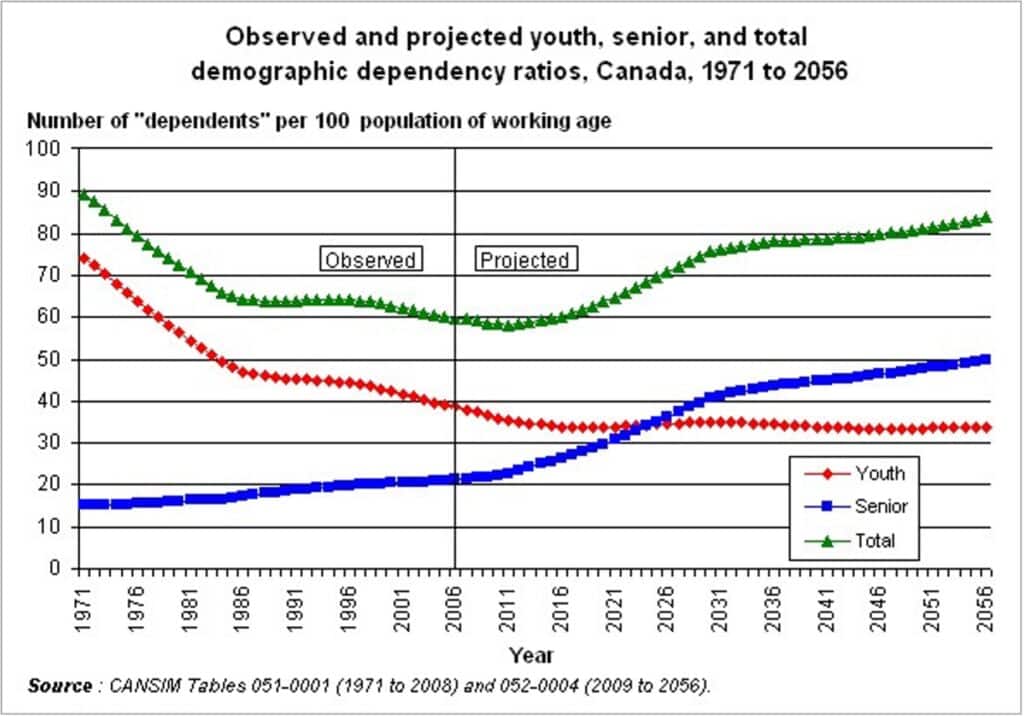

Money for these transfers and services came through taxing the working-age population. As long as the population of younger workers greatly outnumbered those in need of transfers and services, the welfare state seemed destined for success. I am referring to the so-called dependency ratio, which Statistics Canada defines as “the ratio of the combined youth population (0 to 19 years) and senior population (65 or older) to the working-age population (20 to 64 years).”

The dependency ratio is normally expressed as the number of non-contributors per 100 workers. The senior element of it is most telling. In 1971, for instance, for every 100 workers there were 15 seniors; there were 21 in 2006; and projections suggest that by 2056 there will be 50 seniors for every 100 workers. (At the same time, the benefits paid out have generally grown ever-more generous.) In brief, combined with those aged 0-19, this will mean that nearly as many people will be receiving the benefit of the welfare state as will be paying into it on a net basis.

As humanity continued to multiply elsewhere, immigration came to the rescue. If the Canadian population would not grow on its own or at least hold steady, working-age people could be brought in from abroad to increase the number of taxable workers.

Ironically, the Canadian welfare state was instituted at precisely the wrong time, since our fertility rate peaked in 1959 and began steadily to decline. Right from the beginning, then, it was foreseeable that the dependency ratio would become increasingly unfavourable, as our overall population and the number of taxable workers aged, failed to replace themselves and ultimately decreased. It would have taken little foresight to tell that the welfare state would become increasingly unaffordable and mutate from an asset into a liability. As life-expectancies grew, so would the demands on health care, pensions and other social services, and these would become increasingly difficult to pay for.

But that problem was easily solved – or so it seemed. As humanity continued to multiply elsewhere, immigration came to the rescue. If the Canadian population would not grow on its own or at least hold steady, working-age people could be brought in from abroad to increase the number of taxable workers. This remains one of the principal justifications for immigration advertised by the Government of Canada itself.

It was also one of the main reasons for the huge increase in immigration numbers that we saw in the Justin Trudeau years, when the number of permanent residents added each year rose steadily from 2015 onwards until it peaked at about 465,000 in 2023 (along with hundreds of thousands of additional temporary foreign workers and international students). At this point, nearly 100 percent of Canada’s population growth was due to international migration – a phenomenon well analyzed in an earlier instalment of this series by Patrick Keeney.

The “immigration solution” has long been portrayed as an all-purpose remedy, and it seemed to work remarkably well. The Canadian points system was, in theory and often in practice, blind to all characteristics but age, skills, education and language ability. Recruiting the “best and brightest”, many insisted, promoted economic growth, corrected an unfavourable dependency ratio and kept the population growing – as well as contributing to innovation, strengthening institutions and organizations, and enriching Canada’s culture. Best of all, it seemed to do so without public expenditure on training and education, and filled labour shortages along the way. So we have been told over and over – right up to the present moment.

What does a falling fertility rate mean for the future of Canada’s welfare state?

Canada’s welfare state was built on the faulty assumption that the population would keep growing, but the Canada birth rate has collapsed to just 1.26 children per average woman. This raises the spectre of population decline, worsening the problem of insufficient workers to fund rising demands from the growing population of seniors. This imbalance will make programs like pensions, healthcare and Old Age Security increasingly unaffordable, forcing governments into tough choices: raise taxes, slash services, or go deeper into debt.

The Flaws in Mass Immigration

But in more recent days, those claims have become increasingly misleading for two main reasons. First, the welfare state continued to expand through the 20th and into the 21st century, and immigration alone could not sustain it. The result was an enormous amount of borrowing as governments took on ever-more debt to remain solvent. Canada’s public debt may not be as high as that of Japan or France, but it has been rising at an alarming rate and is now at nearly $1.3 trillion for the federal level alone – and twice that when counting provincial and municipal debt, i.e., closing in on 100 percent of GDP.

Second, immigration has lately stopped serving the national interest. Since the Trudeau government’s huge increase in immigration intake, only half the number of new immigrants could ostensibly have contributed much to the economy. The proportion of skilled immigrants shrank to about 50 percent of the total by 2022, and concurrently there was a huge rise in non-permanent, low-skill, low-wage immigration in the form of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and the International Mobility Program (IMP).

In any case, the economic justification for record-high immigration is founded on an erroneous presupposition. This was the idea that large numbers of immigrants would help to pay for the maintenance of our welfare state and social services without also putting a strain on them. But this simply could not be true of family-class sponsorship and the so-called Parents and Grandparents Program, which allow dependent children and elderly adults to join citizens and permanent residents in Canada from abroad. In 2024, these streams welcomed 114,000 persons – none of whom would have made any economic contribution, but rather the opposite.

Moreover, rates of poverty among recent immigrants are higher than those among the established population, and incomes tend to be lower. In 2021, 14 percent of immigrants who had arrived within the past decade lived in poverty, whereas only 6 percent of persons born in Canada did, and 34 percent of all non-permanent residents lived below the poverty line. Moreover, enormous numbers of low-wage, low-skill workers brought in through the TFWP and IMP suppress wages and price Canadians out of the market.

Such facts suggest that immigrants are now more likely to use the Canadian welfare state than the established population – especially among those who contribute to it the least. When we also factor in settlement costs, language training and other such services, the supposed economic gain from immigration seems questionable. And the effects of ultra-cheap foreign labour have included underinvestment in the Canadian workforce and structural underemployment for some of them. Finally, bringing in working-age immigrants does not improve an unfavourable dependency ratio if we also allow and encourage them to bring their parents and grandparents with them.

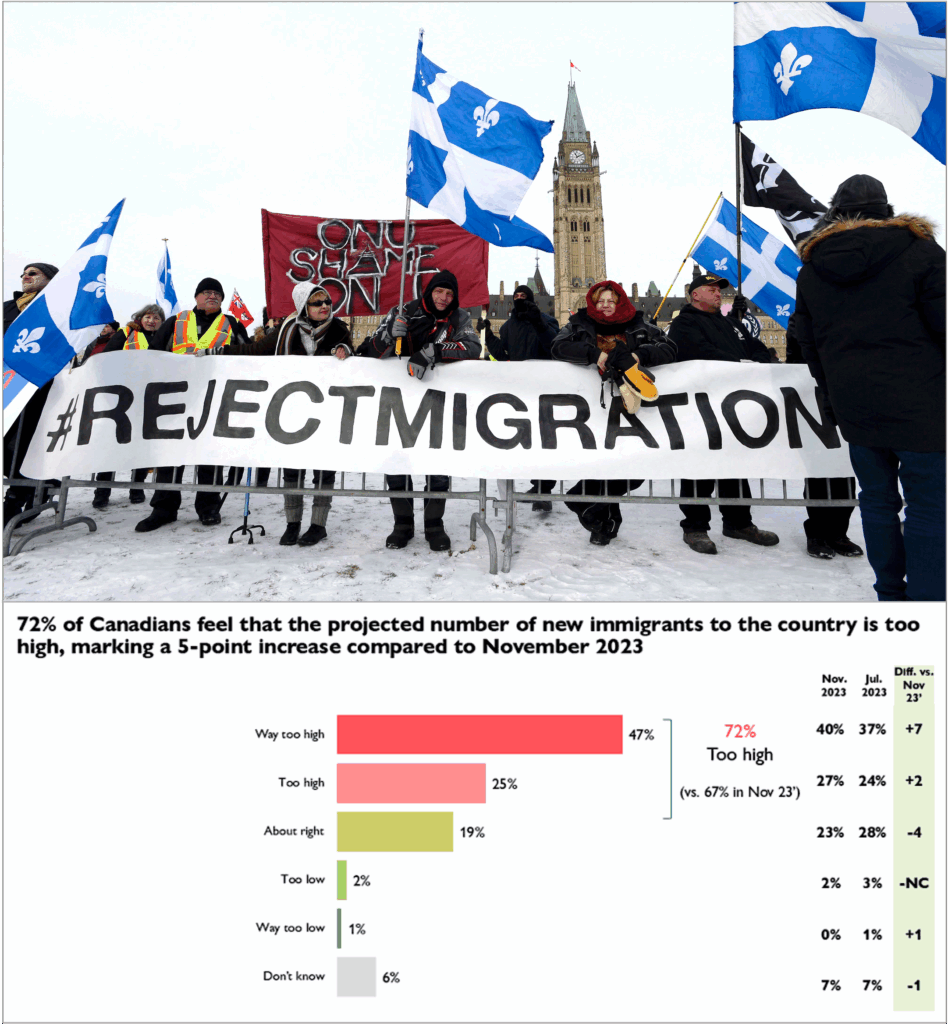

The main political consequence of these effects is that Canada’s old pro-immigration consensus has been shattered. Recent polling suggests that more than half of Canadians believe not only that intake numbers are too high (an opinion held by 72 percent), but that immigration itself harms the country. The old consensus may not recover even if the Mark Carney government lowers overall numbers as promised.

But even if it returned, Canada would still face a problem. In a world of collapsing fertility, there will still be young and well-educated people abroad. But there will not be a large surplus of them seeking their fortunes in other countries. And if Canada continues its evident declines not only in economic performance but social cohesion, public safety, infrastructure quality and government functioning – a slide that immigrant populations have noticed and conveyed back to their country of origin – the very people we might want to bring will be more likely to shun Canada.

The point must be emphasized: the moment when most of the world slides below population replacement levels is rapidly approaching, and Canada cannot therefore expect to have access to a large surplus population of economic immigrants indefinitely.

Moreover, in a world of more seniors and fewer births, the sort of people whom we have needed to prop up our welfare state are exactly those that their native countries are likely to try to retain. There will be a surplus population, however, wherever comparatively high fertility persists a little longer: sub-Saharan Africa. But unless general levels of education and skills training increase significantly there, countries in that region will produce very few desirable immigrants.

Facing The Fertility Factor

The point must be emphasized: the moment when most of the world slides below population replacement levels is rapidly approaching, and Canada cannot therefore expect to have access to a large surplus population of economic immigrants indefinitely. This is an inevitable consequence of the “peak humanity” and “peak child” phenomena mentioned above – and the implications for Canada will be profound.

Immigration will soon cease to be an all-purpose solution, if it hasn’t already. Unless we are willing to accept an ever-lower standard of living, growth and productivity will have to come from investment in the economy and in hiring and training Canadians. Businesses will have to get used to investing much more in skills-training and paying higher wages than they have. Artificial intelligence and automation will increase efficiency and productivity – but algorithms and robots don’t pay taxes and don’t buy things. Technology will not rescue us from a diminishing tax base or improve the dependency ratio, trends that are only worsening.

Why is mass immigration no longer a sustainable solution to Canada’s demographic crisis?

Immigration once propped up Canada’s workforce, but that strategy is faltering. Canada’s population continues to age, increasing the “dependency ratio” of service users to taxpaying workers. Global fertility is collapsing, reducing the supply of young, skilled immigrants. At the same time, more immigrants arrive needing support than in the past, while other policy shifts favour low-wage, less-skilled labour. Canada cannot depend on an international surplus of skilled workers that is rapidly shrinking. In the coming era of population collapse, every country will compete to retain its own talent.

For an idea of what this strain will look like, start with the following facts. Expenditures on Old Age Security (OAS) totalled about $46 billion in 2020; by 2035 the government expects that to more than double to $94 billion. Likewise, pension payouts by the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) are forecast to increase from $49 billion in 2019 to $188 billion by 2050. Increases in health-care spending have long outpaced overall economic growth, and total health-care spending could approach 15 percent of GDP by 2035. Factor in growing fiscal strain amidst substantial increases to defence spending and rising interest payments on the public debt, and you have the makings of a financial and political no-win situation of alarming proportions.

Raising taxes on Millennials and Gen-Zs to pay for the Boomers’ retirement will be a growing temptation. As will doubling-down on low-wage, low-skill immigration. Either will exacerbate the generational tensions revealed in the last election and further destabilize political and social life. But governments will struggle to resist either possibility when faced with an aging electorate averse to any change to the welfare state on which they depend. Cutting elements of OAS, the CPP or health care may also be tempting, but doing so would create other political problems. Sooner or later, provincial governments will almost certainly have to open their health insurance programs to more private-sector competition in order to take some pressure off the public system.

Other possible remedies are only slightly less fraught politically. Policies for keeping seniors productive in the workforce for longer would help somewhat, but would probably not be popular. Japan for instance updated its Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons in 2021 in order to support workers up to age 70. Measures include incentives for delaying retirement, adjusting pension calculations and expanding part-time worker coverage.

Canada would probably also benefit from raising the age of retirement and eligibility for OAS and the CPP from 65 to 70. This has often been considered and should be implemented, though it raises an awkward conundrum. The sooner the retirement age is raised, the more beneficial the effect will be; but resistance will be proportional to the speed of the change. Such measures will lighten the burden a little in the short term, and buy time, but not eliminate it.

So far the discussion has left much to be desired. A report published by the Canadian Senate in 2006 bore the provocative title The Demographic Time Bomb – but offered suggestions only for mitigating the effect of an inevitable population implosion. Similarly, Darryl Bricker and John Ibbitson’s 2019 book Empty Planet concluded that little could be done about a universal collapse in fertility because no one could be asked to have more children – but, they hoped, Canada would still be able to benefit from immigration.

What’s the most effective path to avoid Canada’s outright population decline?

The key to avoiding a demographic collapse is not government slogans or population targets – it’s empowering families to have the children they already want. Nearly half of Canadian women end up with fewer children than they desired. Fixing this gap means removing obstacles like high housing costs, poor infrastructure and social policies that make family life harder. Prosperity starts at home – literally. Restoring fertility is the only way to improve our long-term dependency ratio and ensure the sustainability of the welfare state.

Fundamentally, Canadians must face the fact that we have constructed a modern welfare state on the presumption that our population would always be growing. But we stopped having children two to three generations ago, and the welfare state now depends upon an input – immigration of productive taxpayers – that is rapidly running out. The only long-term solution is raising our fertility rate. It is high time for a national conversation on this subject.

That last point seems especially doubtful to me, but a more fundamental problem takes shape in the way the fertility question is framed. Bricker and Ibbitson are right on one key point: the idea that there should be more babies because the government or someone else asks for them is entirely wrongheaded. No amount of demanding or trying to inspire a higher birth rate will work. The reason for this is that Canadian mothers are generally having fewer children than they themselves would prefer.

The looming problem of the welfare state is merely a consequence of population collapse, and population growth should be our goal not to serve the welfare state, but for its own sake. More children are a good in and of themselves.

A 2023 study by the think-tank Cardus (discussed in this C2C essay) found that nearly half of Canadian women at the end of their reproductive years had fewer children than they had wanted. This amounted to an average of 0.5 fewer children per woman – a shortfall that would lift Canada close to replacement level. The United Nations Population Fund just published a study entitled The Real Fertility Crisis noting the same phenomenon on an international scale. Neither paper prescribes any specific solutions, but their analysis points to the same thing: public policy should focus on identifying and removing barriers families face to having the number of children they want. That is where the public policy discussion should begin.

Our national interest must include making Canada the most desirable place in which to have and raise children. And every future government should be vigilant against impediments to family-formation and raising a desired number of children. Making housing more abundant and affordable would surely be a good beginning. Better planning must go into making livable communities (not merely atomized dwellings) with infrastructure favouring families and designed to ease commuting. But more fundamentally, policy-makers will need to ask and answer an uncomfortable question: why did we allow barriers to fertility to arise in the first place?

Perhaps the most necessary shift is a change in outlook. The looming problem of the welfare state is merely a consequence of population collapse, and population growth should be our goal not to serve the welfare state, but for its own sake. More children are a good in and of themselves, and our economy and welfare state are meant to serve us – not the other way round. It is high time we took this to heart.

Michael Bonner is a political consultant with Atlas Strategic Advisors, LLC, contributing editor to the Dorchester Review, and author of In Defense of Civilization: How Our Past Can Renew Our Present.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.