It is increasingly obvious that Canada’s federal political institutions in totality – the Governor General, the House of Commons, the Prime Minister’s Office, the Senate, the Supreme Court of Canada, the public service and related government agencies – are perceived by many to be failing Canadians. The Confederation appears morbidly ill, and major surgery may be the only way to save it. This year alone has brought three blatant examples of institutional failure.

First, when polls and other indicators were signalling widespread dissatisfaction with the Liberal minority government, rather than allowing Parliament to reconvene in accordance with Constitutional convention and face a confidence vote following the Christmas break, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau requested that the Governor General – a Trudeau appointee – prorogue Parliament. She acquiesced despite there being no compelling reason for the prorogation, only the convention that the GG normally grants such a request from the Prime Minister. The lack of legitimacy behind Trudeau’s move was underscored by the Liberal Party using the extended prorogation to hold a leadership race and convention, installing Mark Carney as Trudeau’s successor. Following all of this, the Liberals finally called the election most Canadians had wanted for a year or more.

Second, after arranging for clearly partisan purposes that the subsequent Speech from the Throne be read by King Charles III himself, the new government refused to prepare and table a budget, as Parliamentary convention in Canada and the mother country demands, opting instead – again out of pure political calculation – to delay its first budget for a full year. An annual budget is the single most important piece of legislation any democratic government needs to produce. The Liberals’ contemptuous – and unpunishable – disregard for this responsibility is more evidence of institutional failure. Third, a non-confidence motion arising from the May 27 Throne Speech was decided on a voice vote, an egregious abuse of Parliamentary convention enabled by the Liberal-appointed Speaker of the House of Commons.

These are just three recent examples; the reader can no doubt think of many more. Canada’s critical institutions of governance are failing to operate in the best interests of Canadians; they need some serious attention.

Canada’s political institutions were formed to suit a particular time – the mid-1800s – and a particular situation – avoiding the absorption into the United States of four British North American colonies: Upper Canada (Ontario), Lower Canada (Quebec), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Time has marched on and the situation is now dramatically different.

At Confederation, Canada’s four new provinces had a population of about 3.4 million. Today, Canada’s population exceeds 40 million spread across ten provinces and three territories stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic ocean. Why would we expect political institutions designed to govern such a small number of people in less than a handful of jurisdictions in such a limited area in response to a particular geopolitical situation to remain appropriate in such vastly changed circumstances?

At Confederation, travel was by horse and (sometimes) buggy, stagecoach, canoe, (some) railway, and steamship; communication was predominately by handwritten paper letter delivered by stagecoach (with telegraphy just getting started). While all those mechanisms of travel and communication remain possible today, they have clearly become sub-optimal. Why then would we expect political institutions designed in that era to remain optimized for today’s world?

Surely it is time to re-examine Canada’s federal institutions to determine whether they should be changed so as to provide Canadians with better governance. For a conservative, the approach to changing something as far-reaching and powerful as a federal state should be, in the simplest of terms: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it; if it is broke, then fix it but without change for change’s sake; and if it can’t be fixed, then replace it with something properly designed to achieve the objectives.” That is the approach taken below, commencing with examining Canada’s federal institutions as they were originally intended.

Original Design

Canada’s federal governance system as described or implied in the British North America Act, 1867. (Source of graphic: Jim Mason)

Canada’s federal governance system as described or implied in the British North America Act, 1867. (Source of graphic: Jim Mason)The main institutions established for the governance of Canada at the federal level at the time of Confederation were:

- The Crown (personified by the Monarch, who was head of state);

- The Governor General (GG) (or Viceroy, the Crown’s representative in Canada);

- The Privy Council for Canada;

- Parliament, consisting of:

- The Senate and

- The House of Commons (HoC); and

- The Judiciary.

The Crown

At the time of the BNA Act, the monarchy in Britain was well along the transition from being an absolute to a constitutional monarchy, in which most legislative and executive power resides in Parliament and the monarch exercises his/her diminishing influence via persuasion, prestige and historical authority.

The Governor General

The BNA Act clearly envisaged a continuation of the pre-Confederation practise whereby the individual provinces were administered by appointed Governors to administer things in the best interests of the monarch. Post-Confederation there was to be a single such person for all four provinces, the GG, with the same “powers authorities and functions” as previously assigned to the four provincial governors collectively, plus the specific power to appoint any assistants, referred to as Deputies, that may be deemed necessary.

Privy Council for Canada

The Privy Council for Canada was clearly envisaged as a significant entity, comprising people chosen by the GG to provide advice and assistance to the Government of Canada – but not be part of it.

Parliament

The BNA Act clearly intended to adapt the existing two-level legislative structure of the Province of Canada, consisting of the Legislative Assembly (lower house) and the Legislative Council (upper house), into a post-colonial instantiation of Great Britain’s bicameral legislative structure (House of Commons and House of Lords), with a House of Commons and a Senate.

The House of Commons was intended to provide representation based on population, at least concerning apportionment of representatives among the four provinces. While there are no precise population figures from that time, apportionment of the original 185 members corresponds to population estimates.

The Senate

The BNA Act clearly envisaged the Senate as providing equal representation by geographic region (which were of varying sizes and would change over time). There were to be 24 senators for each of Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes, with the Maritimes equally apportioned between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Senators were expected to be mature male citizens of property and were to be appointed for life by the GG, who would fill vacancies as they arose. The GG would also have sole discretion to appoint and relieve the Speaker of the Senate.

The quorum for conducting Senate business was set at 15 (i.e., barely 20 percent of the total) but Parliament was allowed to change this if desired. Passage required a “majority of voices” with a tie being considered a defeat. These provisions permitted bills to be passed by just eight senators – 11 percent of the total.

The House of Commons

The HoC was intended to provide representation based on population, at least concerning apportionment of representatives among the four provinces. While there are no precise population figures from that time, apportionment of the original 185 members corresponds to population estimates. The BNA Act (s. 51) goes into great detail about adjusting representation following each census, using 65 representatives for Quebec as a fixed datum and adjusting the three other provinces in relation to that according to their populations from the census.

Importantly, the documentary and historical record is unclear about how the BNA Act intended federal representation to be apportioned within provinces: by population, by geographical district or with a blend. The Act allows future Parliaments to increase the number of members beyond 185 “provided the proportionate Representation of the Provinces prescribed by this Act is not thereby disturbed.” This suggests that rep-by-pop was to be only to the provincial level, with intra-provincial distribution remaining unspecified.

The Act also specifies that, on the first assembly following an election, a Speaker will be elected from amongst the members to preside over meetings of the HoC, that 20 members, including the Speaker, constitute a quorum for conducting business, that matters are decided by simple majority with the Speaker only voting to break a tie, and that the House can continue for a maximum of five years. Note that only 11 out of 185 members (about 6 percent) were thus sufficient to pass legislation.

The British North America Act of 1867 (top left) was the Dominion of Canada’s blueprint, enunciating political institutions aligned with the mother country’s constitutional monarchy. At top right, an 1867 engraving depicting Governor General Charles Stanley opening the first session of Parliament of the new Dominion of Canada; at bottom left, an 1868 view showing the new Parliament buildings in Ottawa with the partially completed Victoria Tower and newly built East Block; at bottom right, Queen Victoria, who granted royal assent to the BNA Act. (Source of top right and bottom left photos: Library and Archives Canada, retrieved from Senate of Canada)

The British North America Act of 1867 (top left) was the Dominion of Canada’s blueprint, enunciating political institutions aligned with the mother country’s constitutional monarchy. At top right, an 1867 engraving depicting Governor General Charles Stanley opening the first session of Parliament of the new Dominion of Canada; at bottom left, an 1868 view showing the new Parliament buildings in Ottawa with the partially completed Victoria Tower and newly built East Block; at bottom right, Queen Victoria, who granted royal assent to the BNA Act. (Source of top right and bottom left photos: Library and Archives Canada, retrieved from Senate of Canada)The institutions of Prime Minister (PM) and Cabinet – critical in our era – are not specifically mentioned in the BNA Act. They may be inferred from the phrase in the BNA Act’s preamble that Canada have “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom,” which at the time had both. Hence these institutions are shown as dashed in Figure 1. Note also, however, that according to here, “The Cabinet, under the leadership of the Prime Minister, directs the business of the Commons, initiates nearly all public Bills placed before Parliament, and has complete responsibility for the initiation of taxes and the recommendation of expenditures. Following established precedent or convention, it is always responsible to the Commons.”

The Judiciary

The portion of the BNA Act dealing with the judiciary is remarkably short. As with other governance aspects, it preserves the judicial structure existing at the time. This consisted primarily of “the Superior, District, and County Courts in each Province.” The authority to appoint and remove judges was vested in the GG, selecting from the bar (lawyers’ association) of each province.

Current Design

While Canada’s federal governing institutions are notionally the same as at Confederation, their roles, functioning and inter-relationships have changed dramatically, as can be seen Figure 2.

The Crown

The monarchy is fully transitioned to a constitutional one and the monarch has an almost entirely ceremonial role. We saw this recently with King Charles III’s reading of the Throne Speech in Ottawa, which was written by the Carney government and handed to the King to read. Having done so, Charles is expected by all parties to have no further involvement in the country’s affairs.

The Governor General

The GG is almost entirely a figurehead, notionally representing the monarch but in reality simply doing what the PM wants. The monarch’s appointment of the GG is a mere formality, with the PM making the actual selection. While the GG retains some substantive prerogatives, convention has neutered even this power. This was seen most recently when the current GG accepted Trudeau’s request for prorogation, a decision that many constitutional experts considered to be constitutionally unjustifiable (and which some attempted, unsuccessfully, to challenge in court).

The position of GG has become perfunctory and ceremonial, and is often used by Prime Ministers to send political messages. As a byproduct, most of the executive tasks formerly performed by the GG have been subsumed by the Prime Minister, Prime Minister’s Office and Cabinet, so that the Government of Canada’s executive and legislative branches have become intertwined and no longer provide effective checks and balances on each other’s behaviour.

Privy Council for Canada

By convention, the Privy Council for Canada nowadays consists of all living and former cabinet ministers, chief justices and former GGs. Provincial premiers have also sometimes been made members on special occasions, like former Ontario Liberal Premier David Peterson, as have prominent Canadians like retired hockey star Maurice “Rocket” Richard. Even some non-Canadians have been appointed. But far from being an active group providing assistance and advice to the government, the Privy Council is a purely titular sinecure. Its last formal meeting was held in 1981 to give pro forma consent to the marriage of the Prince of Wales – now King Charles – to Lady Diana Spencer.

Parliament

The Senate

The Senate is still structured to provide representation by region. Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes retain their 24 senators each, although the Maritimes now include PEI and the region’s Senators are apportioned 10 to each of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and four to PEI. Since 1915, B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba have been considered the Western Provinces region with 24 Senators, allocated six each – fewer than Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. Since 2015, Newfoundland has had six Senators, and each Territory has one, giving the Senate a total of 105. Representation has clearly become a hodgepodge.

Rather than being elected, Senators are still appointed, but this is done on the “advice” of the PM rather than by the GG in substance; that includes the Speaker. Until 2016, PMs generally appointed members of their own party, making the Senate a partisan chamber like the HoC; Senators, indeed, were members of party caucuses.

In 2016 Trudeau, in what many regarded as political theatre, “expelled” Liberal Senators from the Liberal caucus, claiming he aimed to make the Senate less partisan. Concurrently he formed a supposedly non-partisan committee to shortlist potential Senate candidates, and allowed citizens who met the qualifications for Senator to apply for open positions that the new committee would consider. The “expelled” Senators remain Liberal Party members, however, and the Senatorial screening committee is selected by the PM.

The House of Commons

The HoC has grown considerably since 1867, with currently 343 members, largely due to the creation of new provinces but also from the method of determining the number of seats and their allocation. A number of caveats, exceptions and special provisions distort representation by population.

Quebec is no longer the pivotal reference. Rather, a generic “electoral quotient” is used to determine an initial number of seats for each province based on its population. The electoral quotient is the notional number of people represented by each MP in 1985 (during the 33rd Parliament), adjusted following every second census by multiplying by “the average of the population growth rates of the 10 provinces in the last 10 years.” The new value is then divided into the current population of each province to determine its initial seat allocation.

This initial number is adjusted based on:

- That a province must have at least as many seats in the HoC as it does Senators (the “Senatorial clause”);

- That no province have fewer seats than in 1986 (the “grandfather clause”); and

- That any province over-represented in a previous seat distribution not be under-represented in a current distribution (the “representation clause”).

Such seat adjustments are always additions, so some provinces always have more seats than their population alone would warrant. This means, of course, that all the other provinces have fewer seats than they should have based on their population. The HoC’s Speaker continues to be elected by the MPs at the first meeting following an election and has the same responsibilities. Quorum remains 20 members, making 3 percent of members sufficient to pass a bill.

The Prime Minister has acquired, by accretion cemented by convention, all of the substantive powers originally invested in the Governor General – such as appointing senators and judges – and, indeed, effectively appoints the GG as well.

Definition of the physical extent of the electoral districts, or ridings, within a province is done following the allocation of seats to provinces. This is usually done by minor adjustments to existing boundaries but also incorporates feedback from affected areas. Achieving uniform representation by population across the electoral districts in any province is difficult if not impossible.

Prime Minister and Prime Minister’s Office (PMO)

Although not even mentioned in the BNA Act, the position of PM and the associated institution of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) have become the most powerful and influential entities in Canada’s governance structure.

The PM has acquired, by accretion cemented by convention, all of the substantive powers originally invested in the GG – such as appointing senators and judges – and, indeed, effectively appoints the GG as well. In addition, the PM appoints cabinet ministers, ambassadors and the heads of all the governmental regulatory commissions and government agencies. The PM has the final say on legislation and its content before it is introduced into the HoC and on the content of Orders-in-Council (Cabinet decisions). While the position previously was sometimes described as “the first among equals” with respect to Cabinet, there is little doubt that the PM is far more than this. The PM conducts Canada’s foreign policy.

The PMO came to prominence in the late 1960s under Pierre Trudeau. It has no statutory basis and is staffed by temporary political appointees rather than career civil servants. It is responsible for press and public relations, advises on candidates for appointment to the numerous Order-in-Council appointees (everything from Supreme Court of Canada justices to heads of Crown corporations), makes policy, disciplines Cabinet and caucus, liaises with the PM’s party, and runs the PM’s agenda and schedule, thereby controlling access to the PM, where he goes and what he does, and which matters are brought to his attention.

The PM’s chief of staff – again, a political appointee – is arguably the most powerful official in the Government of Canada, after the PM himself. It could be argued that the PM and PMO together form Canada’s de facto government – but with little oversight and few checks and balances. It has been described as more powerful, as a governing institution, than the U.S. White House.

The Judiciary

The structure of the judiciary is quite different than in 1867. This is illustrated in Figure 3 and is a consequence of Sec 101 of the BNA Act, which states that, “The Parliament of Canada may, notwithstanding anything in this Act, from Time to Time, provide for the Constitution, Maintenance, and Organization of a General Court of Appeal for Canada, and for the Establishment of any additional Courts for the better Administration of the Laws of Canada.” As shown in Figure 2, there is now a set of federal courts and the nation’s ultimate legal authority is the Supreme Court of Canada. The PM (either solely or via Cabinet or the bureaucracy) appoints judges not only to these courts but to the superior courts of the provinces/territories, another indicator of the PM’s immense power in present-day Canada.

Strengths and Weaknesses

In keeping with the conservative approach to change described in the introduction, before embarking on a redesign it is appropriate to examine each institution to identify strengths that should be retained and weaknesses that should be eliminated, as well as opportunities in the current environment that could be exploited and threats that should be avoided.

General Considerations

(i) Separation of powers: The complete separation of the three branches of government, as inherent in the original design, is a decided strength. It enables different groups with different expertise to focus on particular aspects of governance while also enabling each to provide some check and balance on inappropriate behaviour by the others. The integration of the legislative and executive branches in the current structure is a decided weakness that should be reduced or, ideally, avoided.

(ii) Appointments: A single individual (previously the GG, now the PM) selecting executive branch deputies, Senators and judges is a decided weakness that magnifies the consequences of incompetence and poor leadership while increasing the risk of nepotism, cronyism or oligarchy, plus the politicization and ideological capture of all branches of government with an associated loss of checks and balances. This weakness is exacerbated in a country governed by the same political party for long stretches of time.

(iii) Terms of Office: The indeterminate and potentially very long terms of office of the various appointees is a decided weakness since it raises – especially combined with the current manner of appointments – the risk of ideological capture, intellectual stagnation and the further loss of checks and balances.

The Crown

As we recently witnessed in the UK with the death of Queen Elizabeth II, under a constitutional monarchy the head of state changes without incident. Though taken for granted by nearly all Canadians, this is by no means the international norm – even today. Contrast this with last year’s change in Syria, a military coup that culminated an immensely cruel and bloody civil war, with one violent, autocratic head of state replacing another. Throughout history, violence and instability have been the norm for changes of government.

Canada over the last 150+ years has been blessed by the uncommon reality that with a true constitutional monarchy – one founded upon and benefiting from the unshakable legitimacy of 1,000 years of constitutional development in the mother country – governments can be changed peacefully and predictably. There is clearly substantial benefit to having an apolitical and unelected though mostly ceremonial head of state with just enough constitutional authority to check any politician potentially running amok.

Whether such a head of state should remain the British monarch or become entirely local is not obvious, however. Our era has witnessed increasing tension between having Canada maintain these ties with the mother country or becoming a republic-in-all-but-name – possibly even a republic by name.

The Governor General

As the embodiment of the Crown in Canada, the same observations as above apply to the GG. What isn’t in doubt, however, are the profound defects in the current, blatantly political appointment process. The role of GG requires someone of learning, gravitas and impartiality, schooled in the Constitution and parliamentary tradition, independent of political machines, and with an unimpeachable record of integrity so as to instil confidence among the citizenry.

The Privy Council

The Privy Council adds no value and should be discontinued.

Parliament

The Senate

A chamber that provides “sober second thought”, i.e., review of government legislation from a longer-term and less partisan perspective than the legislating chamber, is a decided strength of Canada’s federal political architecture. The unelected status of Senators can bolster this strength since it offers the potential, at least, to avoid partisan politicization. The current manner of selecting Senators and their indeterminate (often very long) terms of office are decided weaknesses as they facilitate rank partisan politicization, ideological capture and intellectual stagnation. This problem is greatly compounded when the same political party holds office for long stretches. Moreover, the Senate’s current composition does nothing to ameliorate the regional imbalances reflected in the HoC.

House of Commons

Citizens understanding where laws actually come from, and voters being satisfied that the representatives they elect are actually in charge of proposing, amending and passing or rejecting new laws, is a critical feature for any democracy. Accordingly, having a primary chamber as the sole source of legislation (subject to review, approval and possible amendment by a second independent chamber) is a decided strength as it provides clear lines of authority and accountability for legislation and its impact.

The accreted power of the Prime Minister’s Office is a decided disadvantage of the current design, being as the occupants are political appointees, with vast powers impinging upon all three branches of government, plus partisan political aspects, and accountable only to the PM.

Having this chamber elected by universal suffrage of qualified voters is a further, critical strength as its workings can be seen to reflect the will of the governed. Some people suggest Canada’s current first-past-the-post electoral system seriously erodes or even negates that strength because the preferences of (potentially large) fractions of the electorate can wind up without representation; that is a complicated and contentious topic, addressed below.

Prime Minister and Prime Minister’s Office

The position of PM, ultimately accountable for the outcomes of government policy decisions and associated legislation, and the opportunity to call said person to account in the House of Commons, are decided advantages of the current Westminster-style design.

The accreted power of the PMO is a decided disadvantage of the current design, being as the occupants are political appointees, with vast and ever-changing powers impinging upon all three branches of government, plus partisan political aspects, and accountable only to the PM, all in an office with no Constitutional legitimacy or statutory constraint.

The Judiciary

Canada’s separate judicial branch is a decided strength of its current governmental architecture. The manner of selecting judges and their open-ended and typically lengthy terms are decided weaknesses as they risk contributing to a politicized, ideologically captured, entrenched and intellectually stagnant judiciary. As has largely happened in Canada.

This is especially damaging in a country lacking significant checks and balances on, nor accountability for, judicial opinions, as is the case in Canada, apart from the potentially powerful but rarely exercised check afforded by the “notwithstanding clause” in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. As a consequence, Canada’s judiciary is increasingly enabled and willing to impose its policy preferences via rulings in which the discovery of law is becoming secondary to its modification and even manufacture at the hands of activist judges.

New Design

The proposed new design for Canada’s federal government retains aspects of the original design that have demonstrated their enduring utility, while introducing changes necessary and, it is hoped, sufficient to:

- Correct defects in the original design that have become apparent over time;

- Overcome political stresses of our current era never contemplated in the system’s original design; and

- Provide robust protection against future distortion.

The proposed new design thus combines familiarity and stability with the minimum required modifications.

Architecture

The proposed overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 4. It has three separate branches with distinct but complementary powers and responsibilities, overseen and constrained but neither controlled nor directed by a head of state.

Head of State

This position attempts to retain the benefits described under “The Crown” above as well as the symbolic and ceremonial roles described in various sections above. Several enhancements are added, including:

- Promulgating, by signature, decisions rendered by the Supreme Court of Canada and regulations issued by the executive branch, each as functions equivalent to that already long exercised with respect to laws passed by the legislative branch and regulations issued by the executive branch; and

- Meeting regularly with leaders of the HofC, Senate, executive branch and judiciary to review matters of interest to each. Such meetings would signal to the five participants and the citizenry that none of them is the Canadian government but that each has a complementary role to ensure that Canada functions properly in the best interests of Canadians.

The new design’s substantial extension of the head of state’s promulgation power is aimed at providing an additional, constitutionally based check and balance (currently missing) on the executive and judicial branches. The head of state’s refusal to sign a law, regulation or court decision shall be subject to being over-ridden via a super-majority vote in the HoC and Senate, with requirements that it reflect strong support among political parties and regions of the country. This mechanism ensures that the people’s representatives in the legislative branch hold ultimate authority and responsibility.

The office of head of state carries a term of five years. The occupant should be demonstrably apolitical or, at least, not obviously ideological. Any prospective occupant’s career should demonstrate an understanding of and commitment to Canada’s Constitution, especially preservation of the individual freedom and equality of each and every Canadian, and the gravitas sufficient to perform the required functions in a manner that instills confidence domestically, reflects positively on Canada internationally, and earns respect generally.

The head of state (and a deputy) shall be chosen from the Senators whose terms are about to expire (see later discussion of the Senate), by the Senators who have been in the Senate since the last Head of State was selected. This natural progression should ensure that the characteristics desired in our head of state are met. Removal (in cases of serious wrongdoing or underperformance) can be effected by a two-thirds majority vote in each house of Parliament, including in the Senate a majority from each region and in the HoC from each official party. Any member in either chamber can move for a vote on removal.

The relationship between the head of state and British monarch is left indeterminate because it is recognized that whether to maintain Canada as a constitutional monarchy or become a republic is a monumental question that would need to be put to a popular vote, at the very least. Importantly, the redesigned head of state and their modified role is applicable in either case.

Legislative Branch

As currently, the legislative branch remains responsible for enacting legislation and, also as currently, shall consist of a House of Commons and a Senate, but with changes to both.

House of Commons

The HoC remains the primary of Canada’s two legislative bodies and gains sole responsibility for initiating legislation. It shall continue to be organized around a governing party (the one with the largest number of elected members), an official opposition (the party with the second-largest number of elected members), and the remaining members.

Election of MPs in the newly designed system occurs on a rep-by-pop basis at the provincial level, as was the case in 1867 and is currently. Within each province, representation is determined using proportional representation, so the current concept of ridings and the associated number of them has been rendered irrelevant.

MPs shall be elected through universal suffrage by appropriately qualified citizens from appropriately qualified candidates. Qualifications to be a candidate and/or voter would be:

- At least 30 years of age;

- Citizen of only Canada (no dual-citizenship) and resident in Canada for at least the last five years; and

- No criminal record.

The age requirement is to ensure that the candidate/voter has reached an age that is at least five years past the full development of the brain’s executive functions in the prefrontal cortex, which is generally accepted not to be complete until approximately age 24. The citizenship and criminal record requirements are self-evident. Only citizens of Canada should be involved in making the laws of Canada or choosing those who will make those laws; those with dual-citizenships arguably have divided loyalties. The residency requirement is to ensure that the person’s citizenship is not simply opportunistic. Criminals should not be involved in making the laws or choosing those who will.

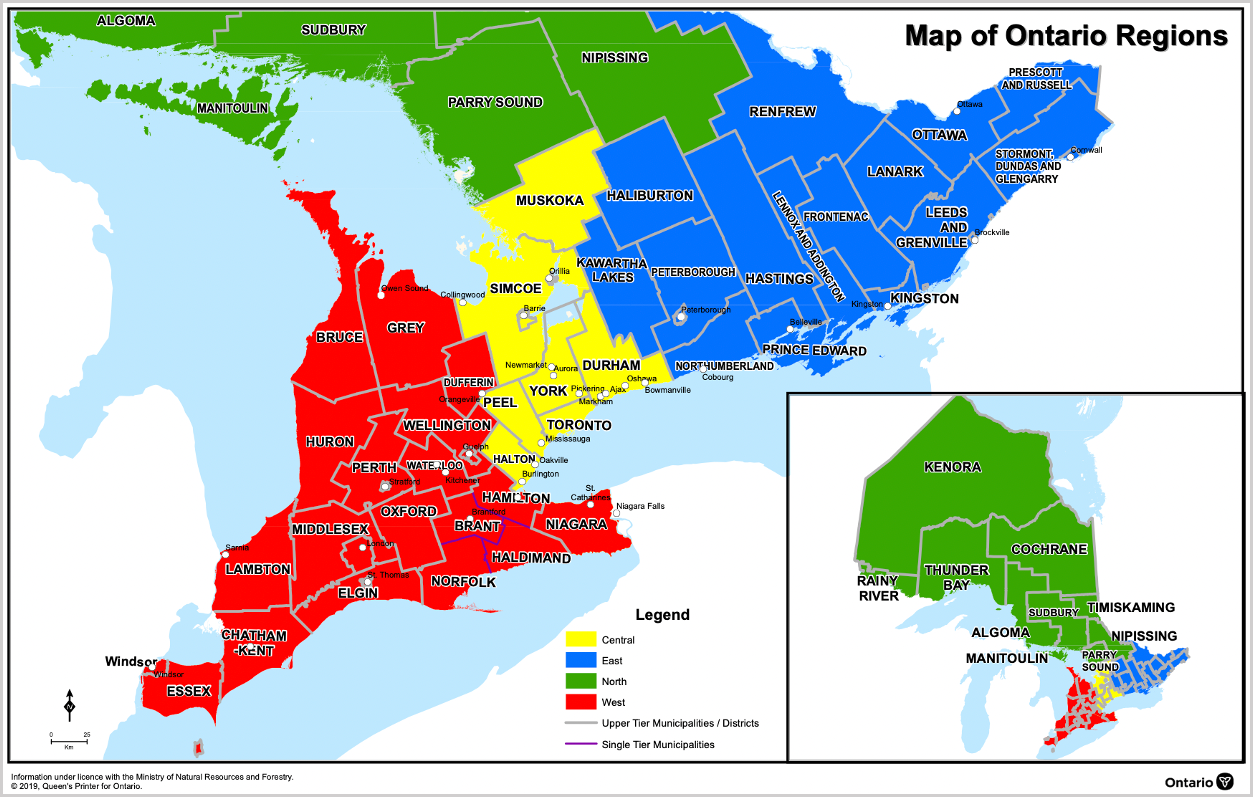

Election of MPs occurs on a rep-by-pop basis at the provincial level, as was the case in 1867 and is currently (more or less). Within each province, however, representation is determined using proportional representation (PR), so the current concept of ridings and the associated number of them has been rendered irrelevant. Instead, a mechanism has been added blending elements of PR with the 1867 system in order to preserve the highly desirable geographical link between residents of a certain area and their Parliamentary representative. Each province’s census divisions (defined by Statistics Canada) are used as the geographical units each to be represented by two MPs, in the manner described below.

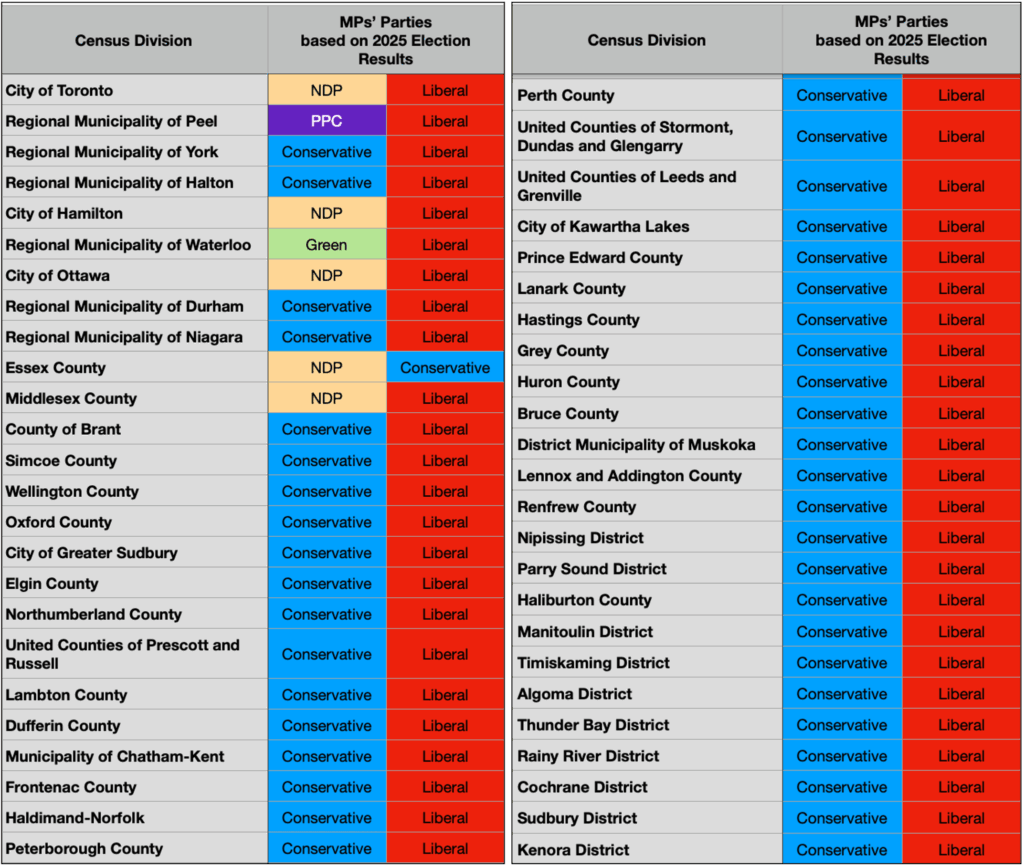

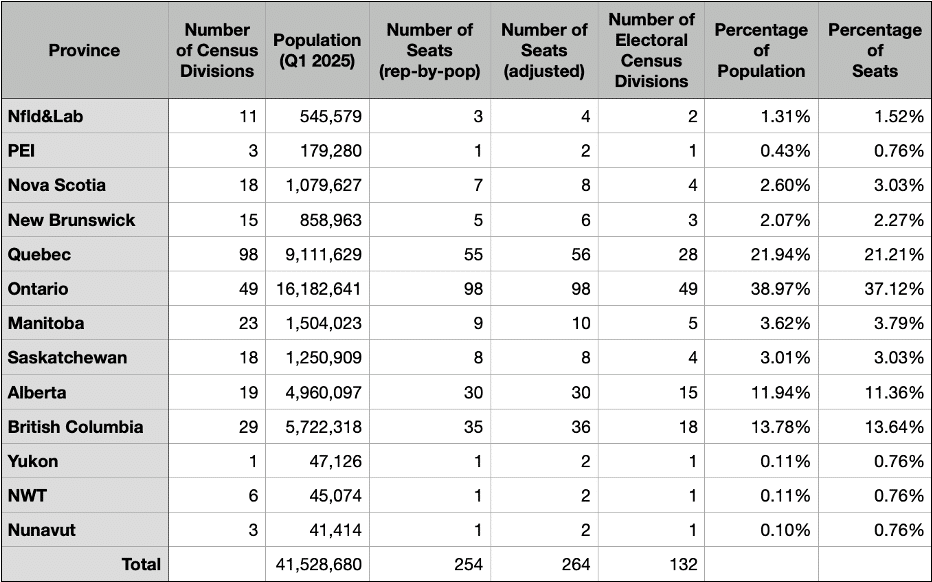

Ontario having the largest population of any province, its population and number of census divisions – 49 – are used to derive each province’s number of MPs, as illustrated in Figure 5. Each division is allocated two MPs, resulting in one representative per approximately 165,000 people. This compares favourably with other English-speaking democracies including about 107,000 per representative in the UK, 183,000 in Australia and 786,000 in the U.S. Scaling Ontario’s allocation by each province’s population results in a total of 254 HoC members, with the allocation for each province shown in Table 1. This calculation will be repeated after every census and representative numbers revised accordingly.

Each census division’s two MPs are selected in the following manner, with Ontario used as a representative example:

- Each party fields candidates in each census division; federal election campaigns unfold as before.

- Voting is conducted and tallied by census division and aggregated to the provincial level to determine the number of seats to be allocated to each party.

- Individual seats are allocated beginning with the party that earned the lowest number, by allocating an MP in the division where it had its highest number (or percentage) of votes.

- The other representative for that division is allocated to the party that obtained the largest number (or percentage) of votes in that division.

- This process is continued until all representative allocations for all but the two most successful parties, after which the remaining divisions each get an MP from each of these two parties.

The outcome for Ontario, using the 2025 federal election’s results, is shown in Table 2.

This approach provides ideologically aligned representation for supporters of each party in the geographical area where they are most prevalent (although not necessarily the largest voting block), while also providing ideologically attuned representation for the voters who constitute that area’s largest ideological block. Additionally, this approach provides every voter with a choice of ideologies either as the channel through which to get help in accessing government services or as the channel of representation in Parliamentary debates and votes. As seen in the table, a division’s two representatives will generally come from both of the two main parties. As in all cases where “customer” choice exists, this can be expected to generate competition between representatives hoping to garner more votes in the next election, improving service and representation.

This approach also better balances urban and rural areas since each census division has the same number of representatives regardless of population or population density. Thus, while large urban areas still have the largest impact on the number of seats accruing to each party, the new allocation method provides urban and rural census divisions with comparable representation and retains the benefit of representation by geographic region that is implicit in the current first-past-the-post system but absent from PR systems without special provisions. The potential for loss of votes to another party already providing representation in any area should help to alleviate the current urban-rural divide.

Two conditions need to be met for these decided advantages to be realized in all provinces: the province’s number of seats must be an even number, and the number of electoral districts must be half the number of seats. As seen in Table 1, these conditions are not present in any other province. Consequently, the new design increases every odd number of seats by one to produce an even number of seats, and transforms Statistics Canada census divisions into new electoral census divisions to form the number required, as shown in Table 3. The resulting minor departure from genuine rep-by-pop and small increase in the overall number of seats are more than offset by the advantages noted above.

Terms and Confidence Votes

The duration of a government between elections is a maximum of four years, as specified in the Elections Act (although the Constitution Act, 1982 specifies five). The PM is barred from demanding prorogation or a snap election, or designating a particular law or measure (including the budget) to represent a confidence vote in the government. Only specific motions of confidence, moved by any party, can cause Parliament to be dissolved and an election triggered. This way a bad budget or other bad legislation can be rejected without causing an election, requiring it only to be amended. Only after making several unsuccessful attempts to amend legislation to satisfy the Opposition (or its own dissident MPs) is a government justified in moving a confidence vote.

Since forming governments by means of formal coalitions between parties – common in countries with PR – or having formal “supply and confidence” agreements between parties – as was the case with the Trudeau government and NDP – are incompatible with this governance model and a perversion of the desires expressed by the electorate, such agreements are prohibited. While there is no way to prevent informal agreements, it is anticipated that voters will punish any parties that engage in such tactics, similar to the NDP in the recent election.

Official Party Status

In order to be an official party in the national Parliament it is only rational that a party must be national in scope. Consequently, a party wishing to gain official status must run candidates in at least 50 percent of the new electoral census divisions in every province (currently, 70 candidates in the 132 divisions), capture at least 5 percent of overall HoC seats, and have seats in at least half of the provinces. This does not preclude purely regionally focused parties from forming, contesting elections, fielding candidates and gaining MPs; it only precludes them from being recognized as an official party in Canada’s Parliament and gaining the nationally funded perquisites that accrue to that recognition.

Prime Minister

The PM shall continue be the leader of the party that gains the most seats in the HoC at any election and retains the current legislative responsibilities, that is, formulation of policies and orchestrating legislation to implement these policies. The notable difference in the redesigned system is that all actions deriving from those policies must be approved via legislation before being taken, except for very limited cases where time is of the essence, in which case, the actions must be subsequently approved by the HoC and Senate within a defined and short period of time.

The PM continues to appoint Cabinet members as deemed necessary to develop policy and the associated legislation. Each Cabinet position shall be resourced appropriately in accordance with a budget approved by Parliament, although it is expected that much of the personnel required can be provided by MPs from the governing party.

Prime Minister’s Office

Given the PMO’s obvious drawbacks, it would be desirable to eliminate it or, at least, make its operations transparent and accountable to Canadians, and constrain its scope of operations. How to do so is not clearly evident, however, and attempts would likely be made to recreate its current functionality through other means, so this matter has been referred for further study.

The Senate

To fulfill its enduringly relevant role as a chamber of “sober second thought” under the new design, providing an independent review of the HofC’s action while minimizing partisanship and ideology, it was concluded that Senators must be: not elected, not appointed, and term-limited.

Accordingly, Canada’s new Senate has equal representation per province, with 10 senators each, and two senators per territory. This is in keeping with the BNA Act’s overall intent and offsets the rep-by-pop imbalance in the HoC, where Quebec and Ontario have 58 percent of the representatives.

Each senator has a term of 10 years, with the longest-serving Senator from each province being replaced every year and from each territory every five years. It is hoped that this will avoid the pitfalls of intellectual stagnation and ideological intransigence that can result from overly long terms, while allowing the insights and wisdom that each Senator brings and develops to be effectively utilized and shared with newer Senators.

Under the new design for the Canadian state, the executive branch is headed by a chief executive officer, assisted by deputies to head each of the government departments and major agencies established by legislation, and includes the associated public service.

Senators are selected at random from the pool of qualified candidates in the province the Senator will represent, the qualifications being identical to those of MP except that the minimum age requirement shall be 40 rather than 30, with an upper age limit of 60. While seemingly a radical proposal, random selection is already used to assemble juries, considered a civic duty. If 12 randomly selected Canadians are considered to have the collective wisdom required to determine someone’s guilt or innocence of a crime and, consequently, to deprive that person of their liberty for potentially the rest of their life, surely 106 randomly selected mature citizens have the collective wisdom to decide the merits of federal legislation. Random selection avoids a Senate composed of individuals operating with externally imposed ideological bias and ensures that all ideological perspectives – indeed, all demographics – present in a province are naturally represented in the Senate.

Because of the much heavier time commitments in being a Senator, including travel and residing away from home, anyone may withdraw their name from the Senate pool. For similar reasons, every Senator shall be adequately compensated, including receiving payments to a retirement investment portfolio of an amount deemed suitable for the significance of the job assignment. The 13 longest-serving senators at any given time form the Senate management team.

Executive Branch

The executive branch is responsible for the effective and efficient execution of the programs and policies established by the legislative branch through legislation, within the budget and the operational limitations and parameters also established by the legislative branch. Under the new design for the Canadian state, the executive branch is headed by a chief executive officer (CEO), assisted by deputies the CEO selects to head each of the government departments and major agencies established by legislation, and includes the associated public service.

The CEO position provides a sensible, coherent combination of the current responsibilities of the President of the Treasury Board, the Minister of Government Transformation, Public Works and Procurement, and the Clerk of the Privy Council. The candidate for CEO is nominated by the PM and subsequently confirmed or rejected by the House of Commons after a painstaking and public questioning by an appropriate House committee. If a candidate CEO is rejected, the PM puts forward another candidate until one is confirmed by the House.

The confirmed CEO will subsequently report to Parliament quarterly on the progress and status of government operations, with a particular focus on the achievement of milestones and adherence to the legislated budgetary plans. Regulations required by and mandated in legislation shall be prepared by the executive branch and presented to the head of state for promulgation as discussed above. The CEO’s term is coincident with that of the government of the PM who appointed him.

The redesigned approach strikes a balance. On the one hand, it ensures that the PM is ultimately responsible and accountable for the execution of government programs in accordance with the policies and legislation the development and enactment of which the PM has also overseen; the CEO is the PM’s “man”. On the other hand, it insulates the execution of these programs from political meddling by the legislative branch and is accountable to and overseen by the totality of the people’s representatives in the HoC.

The Judicial Branch

The overall structure of the judicial branch remains essentially the same but with changes to preclude politicization, ideological capture and intellectual stagnation. The revised Supreme Court of Canada consists of 11 judges, one from each province and one from the three territories combined, each serving a term of 11 years. One judge will be replaced every year in rotation through the provinces and territories. The longest-serving judge is Chief Justice, who is responsible for overseeing the court’s operations. The newest judge acts as assistant to the Chief Justice.

The fundamental requirements for a judge are to know the law and to apply the law, as written in statute and accumulated via precedent, to individual cases, without favour or ideological bias. It is very difficult to assess the degree to which any individual satisfies these requirements until that person has actually been a judge for some time. Consequently, the selection process uses proxies for these traits. The existing proxy for knowing the law is “a barrister or advocate of at least 10 years’ standing at the bar of any province” and is retained.

A proxy for “without favour or ideological bias” does not seem to be specified in the Judges Act, however. Accordingly, judges are to be selected in the following manner. At the lowest level, any lawyer with 10 years’ standing may apply to be a judge and their name will be added to a pool of available judges. Parties to any lawsuit (complainants/prosecution and defendants) will mutually agree on someone from the pool to be the judge for their case. The selected person is paid a judge’s rate for all time incurred during litigation, but does not need to give up their legal practice and returns to it full-time after the case concludes. Pool members who demonstrate while judging that they both know the law and apply it without favour or ideological bias will soon become known to opposing counsel and will be selected frequently, whereas those who have only one or neither attribute will be increasingly ignored. The legal profession will thus self-select from amongst themselves those best-suited to be judges.

While the new system seems more complex than appointing full-time judges, it is no different for any personal-services business in which the professional serves multiple clients. The complexity is more than offset by the immense benefit of developing a pool of judges who are objectively determined, not by a small and potentially politicized cabal but by the full membership of their own profession, to know the law and apply it without favour or ideological bias.

Appeals courts continue to use full-time judges. Each court is filled by drawing randomly from the 10 lawyers who had judged the most cases with none overturned on appeal, a record that affirms the person’s ability to judge without favour or ideological bias. The term of office is 12 years, enabling appeals court judges to gain the experience needed for consideration as a Supreme Court judge.

The Supreme Court of Canada, requiring one new judge per year, will be maintained by selecting, at random, from a list of up to 10 appeals court judges from the appropriate province or the territories. If there are more than 10 such judges, the candidates will be ranked according to the number of cases judged that were not overturned by the Supreme Court. The maximum age of consideration shall be 64 to ensure that the 11-year term can be completed by the mandatory retirement age of 75.

Conclusion

The governance system, institutions and practices envisioned in 1867 and embodied in the BNA Act were designed to achieve a particular set of objectives in a particular geopolitical environment. While they proved overall to be practical, effective and remarkably durable, they are no longer fully suited to today’s political realities, either domestic or international. Moreover, the manner in which the system, the ideas behind it, and the associated practices have evolved has made matters far worse.

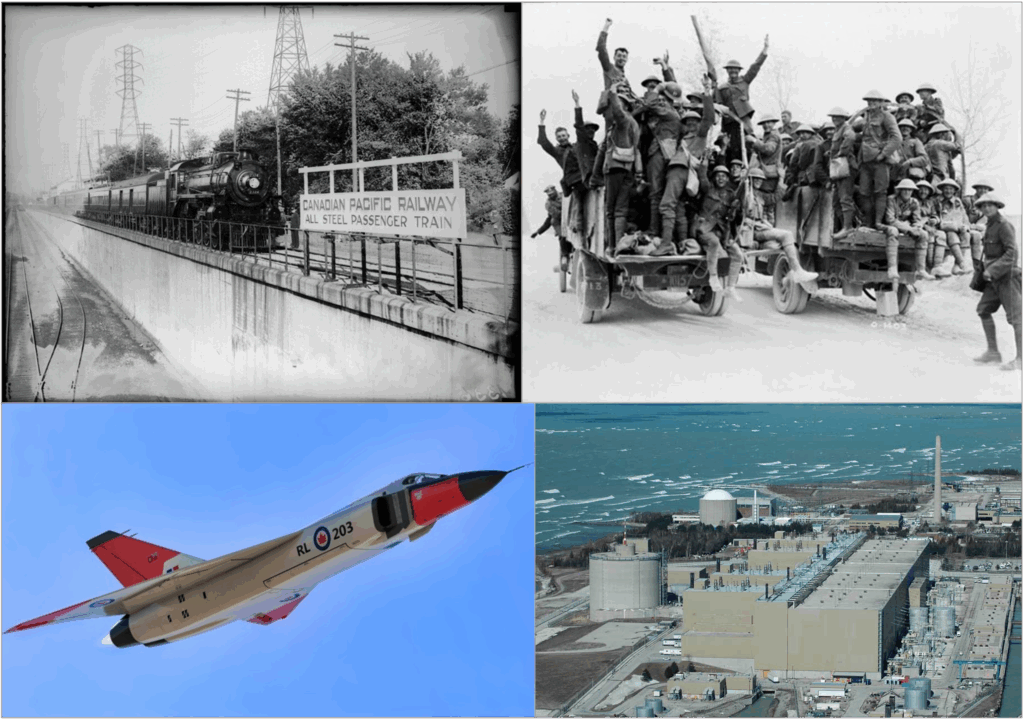

It is earnestly hoped that this new system will prevent further egregious misgovernance and help to reinvigorate Canada to once again be the country whose citizens built the Transcontinental railway, captured Vimy Ridge in the First World War, discovered insulin and built the Avro Arrow jet interceptor.

Consequently, it has proved necessary to re-structure Canada’s national political institutions and design a new governance system, with associated institutions and practices that are not only well-suited to the present political situation, domestic and international, but are robust enough to remain so as Canada’s politics change further over time, and to embody these things in a new Canadian Constitution. This is not a revolutionary act, nor is the impulse underlying it; the purpose and the method are of preservation where possible, repair or redesign where necessary, and restoration of purpose, clarity, order and fairness.

The restructured Government of Canada retains numerous critical aspects of the original system devised at Confederation that have been demonstrated over the last 158 years to be useful, effective and resistant to corruption. It incorporates numerous changes to correct the flaws in the original system that have been clearly exposed over that same time, and to appropriately address the geographic, demographic and “econographic” changes that have concurrently occurred and, as much as possible, to ensure that the federal government’s future operation is always in the best interests of all Canadians. Importantly, it retains almost nothing from the current system, which is such a perversion of the original design as to be the source of most of the current dysfunction and discontent.

It is hoped that the current confluence of Western alienation (increasingly manifesting as separatism), the exposure of Canada’s economic vulnerability by President Donald Trump’s America-first economic policies, the housing affordability crisis stemming largely from the Trudeau era’s ill-considered immigration policies, the severe stress verging on near-collapse of the health care and educational systems due largely to ill-considered federal policies of the same Liberal government, and other problems – all of which can be reasonably argued to be the consequence of the governance system depicted in Figure 2 – will trigger a concerted effort to produce a new design for Canada’s governance system.

It is earnestly hoped that this new structure and system will at once prevent further such egregious misgovernance from occurring and help to reinvigorate and restore Canada to once again be the country whose citizens built the Transcontinental railway, captured Vimy Ridge in the First World War, discovered insulin, built the Avro Arrow jet interceptor, invented a unique nuclear reactor design and developed what was once a world-leading cellphone technology – among many other achievements. The design discussed above is presented as the system to commence this seriously challenging but immensely important and immeasurably valuable undertaking.

Jim Mason holds a BSc in engineering physics and a PhD in experimental nuclear physics. His doctoral research and much of his career involved extensive analysis of “noisy” data to extract useful information, which was then further analyzed to identify meaningful relationships indicative of underlying causes. He is currently retired and living near Lakefield, Ontario.

Source of main image: Anne Richard/Shutterstock.