How often do you hear of parents who take a sick or injured child to a hospital emergency room only to wait for untold hours before admission, treatment or at times even an assessment from overloaded admitting or triage nurses? Think of 16-year-old Finlay van der Werken of Burlington, Ontario, whose heartbroken parents last year had to take him off life support and watch him die after the three of them had spent eight fruitless hours in an emergency room, the boy crying out in pain from sepsis and pneumonia. Closer to home, in a case I know of personally, the severely injured 8-year-old daughter of a carpenter doing some work for us waited in great pain from noon until 11 pm before receiving treatment. She survived, at least.

The crisis in Canada’s health-care system deepens. A May 2025 report from the Foundation for Economic Education entitled Canada’s Ailing National Healthcare is not a Model for America notes that some Canadian emergency rooms “have exceeded 200 percent of their official capacity, forcing patients into hallways and onto floors.” This at least suggests that many workers, doctors and administrators are still trying to serve patients even as the system is buckling. At the same time, the report states, “More than 1.3 million Canadians abandoned emergency room visits due to excessive wait times.” One wonders what ultimately happened to their health. The above report used 2023 data. Since then, Canada’s government health-care monopoly has deteriorated further.

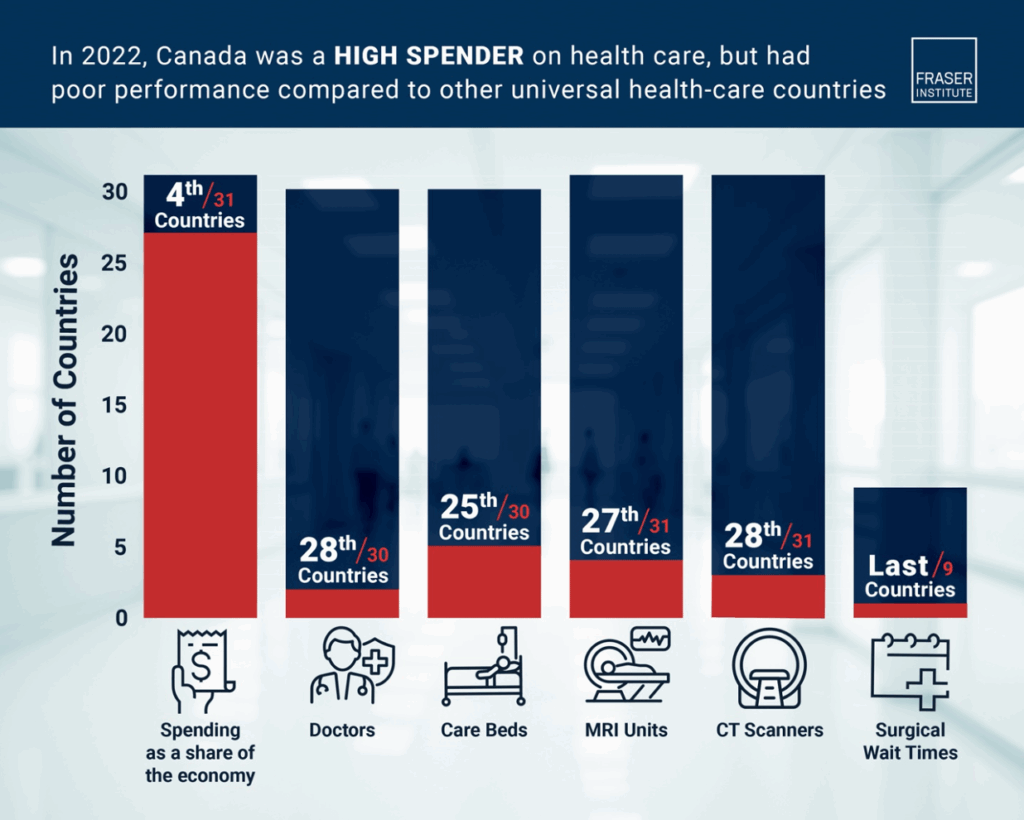

Looking beyond Canada’s problem-plagued emergency rooms, how many families lack a family doctor, mandatory for gaining a referral for tests and specialist care? How many injured workers wait so long for treatment and rehabilitation that their deteriorating skills and mobility make them permanently unable to return to work? A report by the think-tank Second Street (discussed in this National Post article) calculates, using partial data, that “15,474 Canadians died in 2023-24 before receiving diagnostic scans or surgeries.” Because of the large gaps in government responses to Second Street’s Freedom of Information requests, the organization believes the actual nationwide number of deaths-while-waiting is about 28,000 – for just one year. Second Street’s findings are consistent with a 2024 Fraser Institute commentary, by Mackenzie Moir and Bacchus Barua, that references the results of the U.S.-based Commonwealth Fund’s annual health policy survey of 31 high-income countries with universal health care. As of 2022, Canada continued to rank dead-last overall in various metrics on timely access to health-care services.

Today’s problems began, Day explains in his new book, with the 1984 passage of the Canada Health Act in the dying months of the Pierre Trudeau government. ‘But politicians,’ Day notes dryly, ‘didn’t consider how they would fund their plans.’ Sure enough, within a few years, he recalls, ‘funding constraints forced hospitals to reduce operating room hours.’

While running for prime minister, notes Fraser Institute Senior Fellow Nadeem Esmail in a recent commentary, Mark Carney promised to “defend the Canada Health Act and build a health-care system that Canadians can be proud of.” Like so many of Carney’s contradictory, both-sides-of-his-mouth promises, his two objectives cannot be met simultaneously. Canada’s health-care system is broken and crumbling further – and the Canada Health Act shoulders much of the blame. Despite Canada already having one of the world’s most expensive universal health-care systems, Esmail notes, its waiting times to access physicians, diagnostic scans and hospital beds rank as the world’s longest. Simply throwing more money at the problem won’t fix it. Accordingly, as Esmail notes, for Carney to “have any hope of accomplishing the latter [objective], he must break the former.”

How did things get so bad? The abovementioned Commonwealth Fund report notes that all of the countries it surveyed allow or even encourage private-pay access to health care alongside government-funded care. All except one: Canada. That is the key to answering the riddle. And here is a story that helps explain just how we stumbled into our current mess.

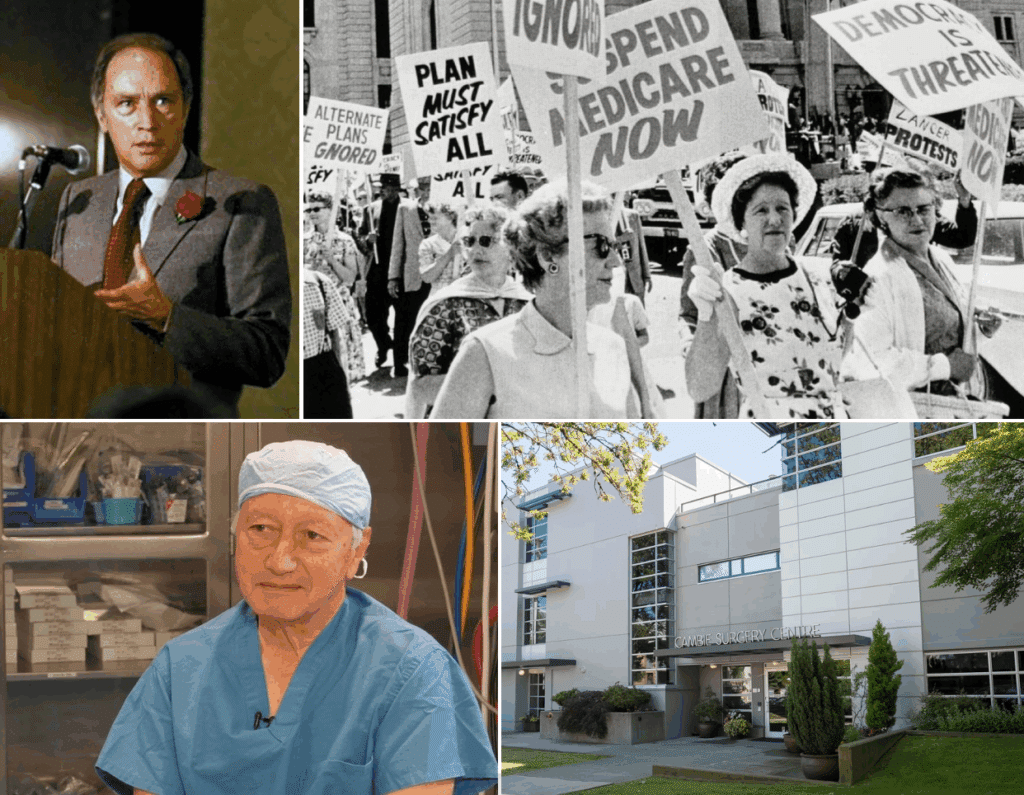

Brian Day is an internationally respected orthopaedic surgeon who as a young Vancouver doctor worked in B.C.’s publicly funded hospital system. Throughout his career Day has demonstrated that he cares passionately about delivering top-quality care to patients and to keep them waiting as briefly as possible. He long ago concluded that accomplishing this consistently would require reforming Canada’s health-care system. Day’s recently published book, My Fight for Canadian Health Care, chronicles his struggle.

How does the debate over private vs public healthcare relate to Canada’s poor performance on access to care?

In the debate over private vs public healthcare, Canada’s position has been clear. The courts continue to uphold restrictions on private care and governments throw more and more money into the public system. Meanwhile, many families lack access to a family doctor, which is mandatory for gaining referrals for tests and specialist care, and hospital wait times get longer, putting patients at risk.

A study of the 31 high-income countries with universal healthcare found Canada ranked dead-last overall in various metrics on timely access to healthcare services. And it was the only country that did not allow or even encourage private-pay access to healthcare alongside government-funded care.

Today’s problems began, he explains, with the 1984 passage of the Canada Health Act in the dying months of the Pierre Trudeau government. “But politicians,” Day notes dryly, “didn’t consider how they would fund their plans.” Sure enough, within a few years, he recalls, “funding constraints forced hospitals to reduce operating room hours. Surgical time allocated to me and my colleagues was progressively cut from twenty to five hours per week, often even less due to emergency cases.” This was a classic case of government rationing access to health care by constraining the system’s ability to get things done.

And so, writes Day, “Together with a small group of friends and supporters, I decided to establish a small private surgical centre.” The Cambie Surgery Centre opened in 1996 – and soon proved that privately delivered health care could both operate more efficiently than government hospitals and directly benefit those same hospitals. “Our procedures encompassed all surgical specialties – and we often did them at 40-50 percent of the [public] cost,” Day writes. “Prior to our opening, many complex procedures were only performed in public hospitals. By transferring them to our centre, public hospital wait times were reduced and capacity was increased.”

For years, Cambie Surgery operated without much government interference, amassing a following of grateful patients who quietly spread the word. Until 2009 – when the B.C. Nurses Union pressured the provincial government to shut down private clinics under the new provincial Medicare Protection Act. Thus began a long, tortuous and costly legal challenge that went from the Provincial Court to the B.C. Court of Appeal. It ruled against Cambie Surgery despite the judge’s acknowledgement, as the book recalls, that “Wait times in considerable measure flow from government rationing of health care.” (C2C explored the Cambie legal case here and here.)

Another comment of the appeal court judge – “I will await the Supreme Court’s decision” – made it clear that he fully expected the case’s ultimate fate to lie with the Supreme Court of Canada, whose mandate is to decide legal matters of “national Interest”. A retired Supreme Court justice who had been advising Day’s challenge even predicted that, “They’ll have to hear the case because very few matters are more important than health care.”

What is the Canada Health Act and what has been its impact since its passage in 1984?

The Canada Health Act, passed in 1984 during the final months of Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government, is the legislation that underpins Canada’s public healthcare system. It demands provinces provide medically-necessary health services to all Canadians without patient charge. However, funding constraints mean governments have effectively had to ration access to healthcare, leaving Canada with a system that is among the world’s most expensive, yet least effective. One organization estimated that the number of Canadians who died in 2023-24 while waiting for diagnostic scans or surgeries was about 28,000.

Astoundingly, on April 6, 2023 the Supreme Court announced it would not hear Cambie’s appeal. The current Prime Minister Trudeau – Justin – had vowed to defend the Canada Health Act; to some, the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the Cambie case suggested that Canada’s top court was no longer independent of government. Cambie Surgery’s days as a private provider of government-insured services were at an end; today it still operates as a provider of uninsured services such as sports medicine.

The overarching problem in Canada’s health-care system is not the specific number of doctors, or the exact level of spending, or the precise number of regulations; it is that the system itself is a dysfunctional government-run bureaucracy, made much worse by the disallowance of private competition.

The evidence not only from the Cambie Surgery Centre but from around the world is clear: access to privately operated health care simultaneously delivers great outcomes for the patients who pay for it and relieves demand pressure on government-run facilities, improving overall health care. Canada’s provinces, which have primary responsibility for health care, should be expanding the role of private health care. This needs to be facilitated through reforms to the Canada Health Act, which carries the federal funding hammer.

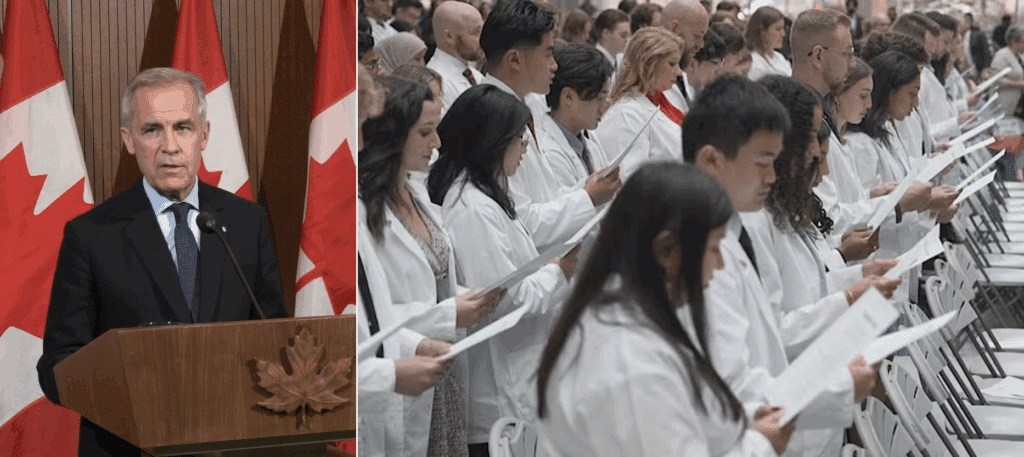

But how does Carney now plan to fix our dangerously dysfunctional health-care system? A Liberal Party election campaign media release entitled “Mark Carney’s Liberals to protect and modernize Canada’s public health care system” promised to “add thousands of new doctors” to the public system, to spend vastly more on health care, and to slash – as if by magic – health-care waiting times. Meanwhile, the same document snidely denigrated private health-care delivery. Its goals are utterly unrealistic.

Has anyone in Canada tried to operate a private clinic offering government-insured services alongside the public system?

Yes, a notable example of a private clinic in Canada was the Cambie Surgery Centre, which opened in Vancouver in 1996. The private centre performed surgical procedures at 40 to 50 percent of the public cost, and by transferring complex procedures to the centre, public hospital wait times were reduced. However, following pressure from the B.C. Nurses Union in 2009, a legal challenge was initiated under the province’s Medicare Protection Act. A B.C. Court of Appeal ruled against Cambie Surgery and in 2023, the Supreme Court of Canada announced it would not hear Cambie’s appeal, ending its ability to operate as a private provider of government-insured services.

Adding more doctors, for example, would require a profound increase in medical school enrollments, something that this recent Globe and Mail article points out would be enormously difficult. It’s also worth noting that enrolment in medical schools was deliberately restricted starting several decades ago in order to limit the supply of new doctors, on the theory that more doctors would provide more care, resulting in higher costs (as Day explains in this C2C article). Another form of rationing.

The overarching problem in Canada’s health-care system is not the specific number of doctors, or the exact level of spending, or the precise number of regulations; it is that the system itself is a dysfunctional government-run bureaucracy, made much worse by the disallowance of private competition. Government-run bureaucracies almost always fail, and usually at a very high cost. There’s no higher cost than the tragic toll taken on millions of ill, injured or dying Canadians.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.