In late July CBC News reported that a Christian singer was to perform that week at the York Redoubt National Historic Site near Halifax. CBC’s Brett Ruskin got us up to speed. “Sean Feucht is a religious leader,” he told host Natasha Fatah. “He ran as a conservative Republican candidate back in 2020 in the State of California and lost. During the Covid-19 pandemic, he spoke out against and went in violation of the mask regulations and the large group gathering regulations. He’s spoken out in support of Donald Trump and against abortion and 2SLGBTQ+ rights.” CBC then played a clip from Larry Stewart, a “local resident” who demanded that Parks Canada cancel Feucht because his “views” are “anathema to the principles of Canada.”

The federal bureaucrats obliged, yanking Feucht’s permit the day before the show, forcing it to relocate. Parks Canada issued a statement claiming this was necessary because of “potential impacts to community members, visitors, concert attendees and event organizers” and “heightened public safety concerns.” It did not provide any evidence, leaving one to reasonably conclude its real “concerns” were the content of Feucht’s speech – those hideous, un-Canadian views of his.

The cancellations then fell like dominoes: Charlottetown, Vaughan, Winnipeg, Moncton, Quebec City, Gatineau and Abbotsford. Ahead of a small concert Feucht planned inside a Montreal church, Montreal Mayor Valerie Plante’s spokesperson told CBC News the featured singer “goes against the values of inclusion, solidarity and respect” and that “hateful and discriminatory speech is not accepted in Montreal.” Though the concert went ahead, the city then slapped the church with a $2,500 fine.

Whether Feucht’s words are offensive, hateful or otherwise depends on your views. As the Vancouver Sun noted in a round-up of his controversial speech, he has called the Black Lives Matter movement “shady” and a “fraud,” said those who support Pride Month have a “demonic agenda seeking to destroy our culture and pervert our children,” and criticized abortion. Most controversially, Feucht posted on X that people protesting a hospital’s decision to end transgender surgeries on kids were “demonic.” He backed this up with a passage from Matthew 18:6: “If anyone causes one of these little ones – those who believe in me – to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.”

As a gay person, I obviously don’t agree with many of Feucht’s opinions. But as a civil rights lawyer and advocate for freedom of speech, these cancellations disturbed me far more than anything I’ve heard Feucht say. By cancelling his shows based on their content – or their possible future content, since they hadn’t even happened yet – the officials in charge violated the rights to free expression of Feucht and thousands of would-be audience members. If governments can halt concerts or other events because they or a number of noisy citizens don’t like the featured participants’ views, do we really have freedom of speech in Canada?

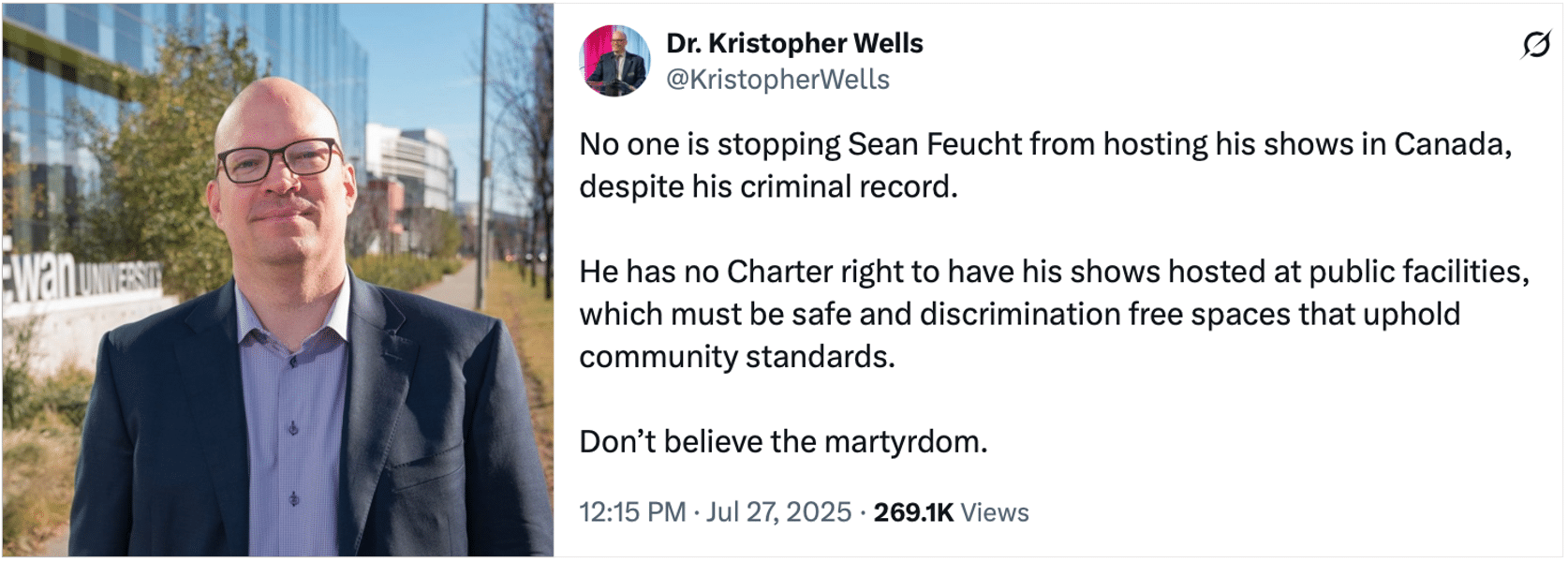

Rationalizing censorship: Senator Kris Wells argues that as an American, Feucht “has no Charter right” to perform in public spaces – thereby ignoring the incontrovertible Charter rights of Canadians who wish to see him perform. (Source of photo: SARAVYC/UBC)

Rationalizing censorship: Senator Kris Wells argues that as an American, Feucht “has no Charter right” to perform in public spaces – thereby ignoring the incontrovertible Charter rights of Canadians who wish to see him perform. (Source of photo: SARAVYC/UBC)The Feucht incident sparked a torrent of ill-informed and misplaced commentary about the limits of freedom of speech. Senator Kristopher Wells (appointed by Justin Trudeau in 2024) claimed Feucht has “no Charter right to have his shows hosted at public facilities, which must be safe and discrimination free spaces that uphold community standards.” Others suggested Feucht has no Charter rights at all because he’s American. That’s not true, but even if it was, what about the Charter rights of those who wanted to see the shows?

While I suspect most of the cancellations were motivated by the authoritarian urge to censor, some may be due to good-faith confusion on the legal limits on freedom of speech in Canada. That confusion is understandable. The leading Supreme Court of Canada decisions on freedom of expression have consistently failed to identify a principled basis for when expression can be limited. This is despite the fact that a relatively straightforward rule was already there for them to cut and paste: it came from solid pre-Charter Canadian jurisprudence and, in turn, the philosophy of John Stuart Mill.

That “golden rule” was that governments should never be allowed to outlaw expression based on the content of the ideas the speaker wants to put forward. They can justifiably limit expression, however, where it takes on harmful forms or threatens imminent physical harm. But this is not the current law in Canada. Despite some recent improvements made via Supreme Court of Canada rulings on Charter cases, it remains unclear what speech can be legally censored in Canada.

Here is where things now stand: utter confusion. Governments across Canada think they can pass all kinds of insidious content-based restrictions by citing the possibility of hateful or discriminatory speech. The courts’ long failure to come up with a principled line on what can be censored and what can’t means that the Feucht cancellations may – or may not – be upheld.

The Development of Free Speech’s “Golden Rule”

English philosopher John Stuart Mill crafted what became Western civilization’s most famous defence of free speech in his 1864 essay On Liberty. Mill argued that no democracy is “completely free” unless its people are entitled to human liberty, which he said consists of three freedoms: the freedom of expression, the freedom to pursue one’s own goals as long as they don’t harm others, and the freedom of assembly. On free speech, Mill offered the oft-cited rationale that, “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.” Silencing that minority opinion not only robs those who agree with the opinion of their rights but also those who disagree and may be “deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth.”

What Mill was trying to illustrate was that suppressing the idea that corn dealers starve the poor would violate the constitutional protection for free speech. Riling up the excited mob right outside the corn dealer’s house, on the other hand, is different; it is an incitement to commit violence.

Less famously, Mill took on the question of what limits on freedom of speech may be justified. “An opinion that corn-dealers are starvers of the poor, or that private property is robbery, ought to be unmolested when simply circulated through the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered orally to an excited mob assembled before the house of the corn-dealer, or when handed about among the same mob in the form of a placard,” Mill wrote. “Acts, of whatever kind, which, without justifiable cause, do harm to others, may be, and in the most important cases absolutely require to be, controlled by the unfavourable sentiments, and, when needful, by the active interference of mankind. The liberty of the individual must be thus far limited.”

What Mill was trying to illustrate was that suppressing the idea that corn dealers starve the poor would violate the constitutional protection for free speech. Although this opinion might eventually lead to harm to the corn dealer, expressing ideas, however controversial, radical or offensive, must be protected so that we can pursue truth. Riling up the excited mob right outside the corn dealer’s house, on the other hand, is different; it is an incitement to commit violence. The mob might burn the house down, smash the windows or beat the corn dealer.

Other forms of legitimately preventable expression include punching someone in the nose or mounting a blockade. In all those cases, the risk of imminent physical consequences can justifiably be prevented by law if necessary because the law is not targeting an idea. The mob might also be so loud that the corn dealer can’t live peacefully in his house. Such a nuisance form of expression can also justifiably be controlled. Laws against nuisance noise levels don’t target the content of the idea, but the form and/or the imminent physical consequences.

In the United States, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes – one of America’s most famous jurists, who authored a number of enduring rulings concerning rights, freedoms and the limits thereof – seemed to read Mill this way too, although not until it was too late for anti-war activists. In 1919, the court heard appeals in three cases that had found First World War dissidents guilty of the Espionage Act’s ban on obstructing the war effort. In Schenck, the court upheld the conviction of socialist Charles Schenck, who had circulated literature that “intimated that conscription was despotism in its worst form, and a monstrous wrong against humanity in the interest of Wall Street’s chosen few.” Writing for a unanimous court, Holmes applied the free speech test that existed at the time, which said that if words created “a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent,” they can be outlawed.

The problem with that standard was it allowed governments to imprison people as long as they labelled the idea dangerous. To do so undermines the very purposes of free speech, among which is providing the opportunity of exchanging truth for error. It’s also very hard to square that test with the clear text of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, which states, “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech.” In the second Espionage Act case, Debs, Holmes for a unanimous court upheld the 10-year prison sentence for Eugene Debs’ crime of speaking out against the war.

Then the court took its summer break – and Holmes changed his opinion on the limits of free speech. In a third Espionage Act case that fall, Abrams, Holmes concluded that a socialist who advocated for munitions workers to join a general strike couldn’t be convicted because there was no “present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress setting a limit to the expression of opinion…” But Holmes’ colleagues outvoted him, 7-2.

His views eventually prevailed, however, when the 1969 Brandenburg decision implicitly affirmed Holmes’ assertion from half a century earlier that the danger to others must be immediate. The Supreme Court ruled that speech can be limited where it is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and is “likely to incite or produce such action.” In the United States, that golden rule was with few exceptions now the supreme law of the land.

What is the “golden rule” for protecting freedom of speech?

The “golden rule” for protecting freedom of speech is the informal name used to describe a principle derived mainly from the philosophy of late-1800s English philosopher John Stuart Mill, which holds that governments should never be permitted to outlaw expression or engage in censorship based on the content of the ideas a speaker wishes to present. Governments can, however, justifiably limit expression when it takes on harmful forms or threatens imminent physical harm.

Legitimately preventable forms of expression include inciting others to commit violence, such as riling up an excited mob outside a person’s house, or creating a nuisance, such as excessive noise. The golden rule principle distinguishes between suppressing an idea itself, which must be protected so that people in a free society can pursue truth, and regulating its form or immediate physical consequences. This principle became the law of the land in the United States with the 1969 Brandenburg case, and was largely accepted in Canadian jurisprudence until the arrival of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, but became muddled in subsequent court cases.

Canada Gets It – For a Time

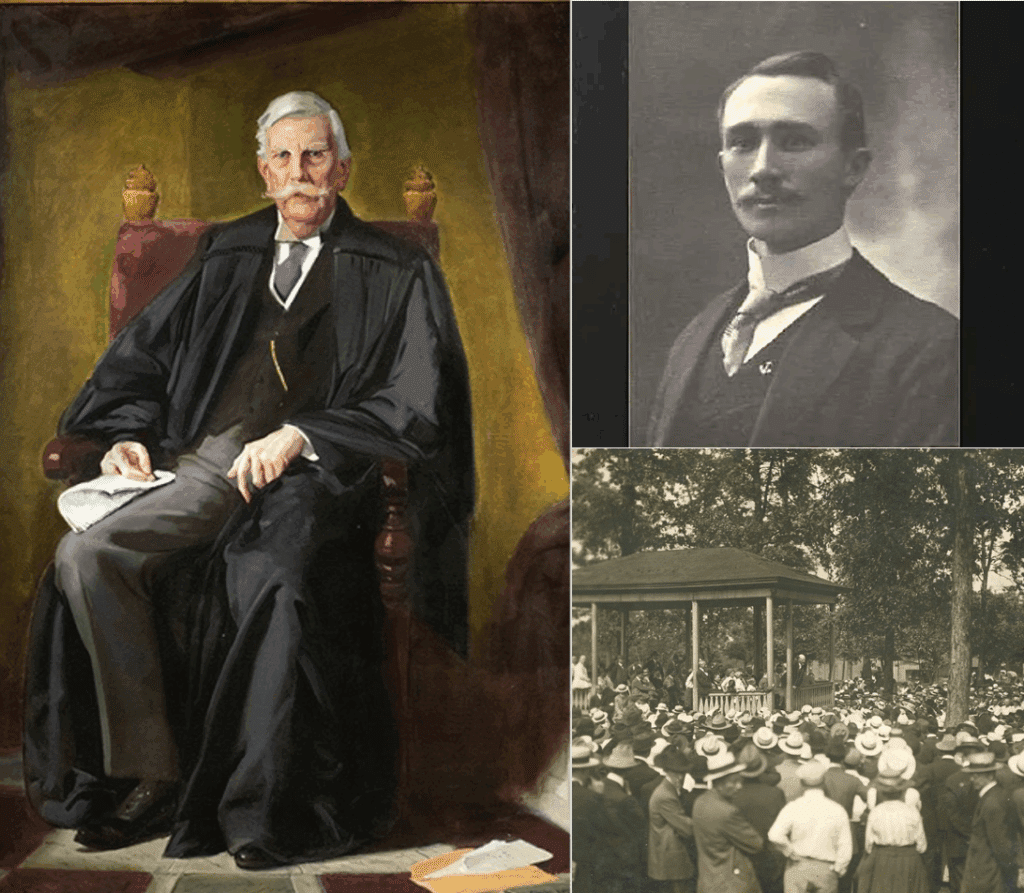

Many of Canada’s 20th century Supreme Court judges also understood that governments mustn’t seek to quash ideas. In the 1938 Reference Re Alberta Statutes, Justice Cannon found that Canada’s Constitution protects a person’s “fundamental right to express freely his untrammelled opinion about government policies and discuss matters of public opinion.” Canada did not have a written bill of rights, but the majority found that when the drafters of the British North America Act (later renamed the Constitution Act, 1867) wrote in the preamble that Canada’s provinces were to have a constitution “similar in principle to the United Kingdom,” that included the UK’s unwritten constitutional protection for free speech. The court accordingly overturned Alberta’s censorious Accurate News and Information Act.

In the 1950 Boucher case, the court went further, protecting the right to discuss “dangerous” ideas in overturning the conviction for seditious libel of a Jehovah’s Witness who had handed out pamphlets entitled “Quebec’s Burning Hate for God and Christ and Freedom is the Shame of Canada.” Justice Ivan Rand wrote that this conviction could not stand in a society where “disagreement in ideas and beliefs…on every conceivable subject…is of the essence of our life.”

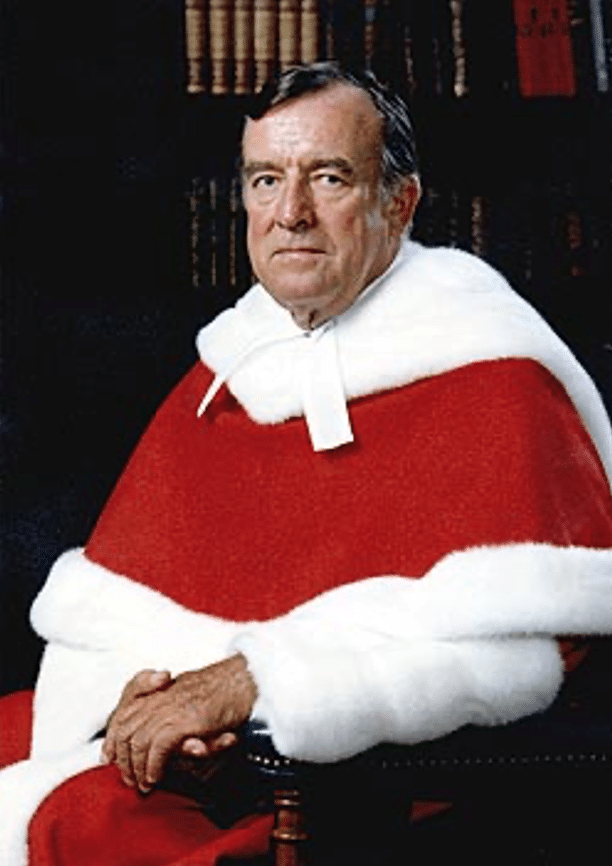

When the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms became part of Canada’s supreme law in 1982, the work of drawing a principled line was mostly done for Chief Justice Brian Dickson’s Supreme Court, which would hear the first Charter cases. The golden rule was now there for the taking and could easily have been relied upon by Canada’s legal establishment ever since.

Three years later in Saumur, Rand articulated the distinction between shutting down ideas and shutting down expression that is harmful in form or has immediate physical consequences, when he overturned a Quebec City bylaw against distributing literature without police permission. The law could not stand, he wrote, because it aimed at regulating “the minds of the users of the streets.”

Then in 1957, the Court issued Switzman, perhaps the high-water mark for free speech in Canada. The court struck down Quebec’s Act to Protect the Province Against Communistic Propaganda, which allowed the government to padlock any property used to discuss communism. Echoing Saumur, Rand wrote that the statute was an attempt to prevent “a poisoning of men’s minds,” to shield people from exposure to “dangerous ideas” and to protect them from their own “thinking propensities.” Rand declared that, “apart from sedition, obscenity and criminal libel,” the “literary, discursive and polemic use[s] of language are, in the broadest sense, free.”

Thus, when the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms became part of Canada’s supreme law in 1982, the work of drawing a principled line was mostly done for Chief Justice Brian Dickson’s Supreme Court, which would hear the first Charter cases. Section 2(b) had constitutionalized Mill’s thesis that “everyone” is entitled to “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication,” subject only, as section 1 of the Charter states, to “such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” The golden rule was now there for the taking and could easily have been relied upon by Canada’s legal establishment ever since.

![Canada’s freedom of speech high-water mark: In Switzman of 1957, Justice Ivan Rand struck down Quebec legislation outlawing “Communistic propaganda,” concluding the province’s intent to protect people from “dangerous ideas” undermined the “discursive and polemic use[s] of language” which “are, in the broadest sense, free.”](https://c2cjournal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Inset6-4-scaled.png)

Canada’s Courts Lose the Plot – and the Long Retreat Begins

But Dickson failed to build on the work before him – a failure that haunts Canada to this day. In the first big post-Charter freedom of expression case, Irwin Toy, the Court in 1989 upheld a Quebec law banning certain advertisements aimed at children. Had Dickson read On Liberty, he would have understood that freedom of expression applies “only to human beings in the maturity of their faculties,” so this was a truly easy case. He could simply have stated that, since young children have no independent legal rights to free expression, the toy company couldn’t use the Charter as a defence.

Instead, Dickson used the case to expound on the limits of freedom of expression. He started off strongly. “Freedom of expression was entrenched in our Constitution,” he wrote, “so as to ensure that everyone can manifest their thoughts, opinions, beliefs, indeed all expressions of the heart and mind, however unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream.” And he seemed at first to recognize the crucial distinction between suppressing ideas and suppressing harmful forms of expression: “While the guarantee of free expression protects all content of expression, certainly violence as a form of expression receives no such protection.”

How did the Supreme Court of Canada’s approach to free expression change after the 1982 adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

Before the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was adopted in 1982, Supreme Court of Canada jurisprudence strongly protected free expression, affirming in cases like the 1957 Switzman decision that the use of language was, in the broadest sense, free.

After 1982, the court under Chief Justice Brian Dickson failed to build on this precedent. The 1989 Irwin Toy decision created a new test that led to ad hoc rulings, and the 1990 Keegstra decision upheld criminal hate speech laws in Canada by finding a Criminal Code provision against willfully promoting hatred to be constitutional. This shift was based partly on the belief that people cannot be trusted to think rationally. The result is a state of legal confusion in Canada, where it remains unclear what speech can be legally censored, amidst a political atmosphere of increasing censorship by government authorities, professional organizations and large corporations.

Then he lost the plot. Although “it might be difficult to characterize certain day-to-day tasks, like parking a car, as having expressive content,” Dickson wrote, he found that such things will still be constitutionally-protected speech as long as they are an attempt to convey meaning. For example, “An unmarried person might, as part of a public protest, park in a zone reserved for spouses of government employees in order to express dissatisfaction or outrage…” But while such a thing is certainly expressive, there’s no reason to believe it is constitutionally protected expression. A law against illegal parking is not targeting an idea or the content of speech; it’s targeting a nuisance form of expression.

This error led Dickson to formulate what become known as the Irwin Toy test, which finds that any attempt to convey meaning, except for expression with a physically violent form, is prima facie protected, as long as the applicant can show that their expression furthers one of three state-sanctioned objectives for freedom of speech: self-government, truth-seeking or self-actualization. But as scholars such as Jamie Cameron have pointed out, practically any expression one can think of furthers one or more of those objectives. The result is that every Charter case gets decided in an ad hoc way.

And since Dickson drew no principled line in Irwin Toy, the Supreme Court became ever-more reliant upon its new “Oakes test”, which had been created in 1986 to determine, per section 1 of the Charter, what limits on our rights and freedoms are “reasonable” in a free and democratic society. While the Oakes decision is a complicated story in itself, in substance it became a green light for censorship because it meant that if the government can satisfy the courts that the targeted speech is subjectively harmful and the government’s objectives and means of suppressing it are somehow “proportional” to the degree of harmfulness, then the government can outlaw the speech. That in turn led to ad hoc and subjective decision-making because it was left to individual judges to decide how harmful or dangerous a particular instance of expression a government wanted to ban might be.

And so it was when the Supreme Court was presented in 1990 with its most important freedom of speech case yet. James Keegstra had taught students in his rural Alberta school that Jews were treacherous, subversive, sadistic and money-loving child-killers. A jury found Keegstra guilty of the offence of willfully promoting hatred (now section 319(2) of the Criminal Code). Keegstra argued that the hate speech law violated the Charter’s section 2(b) guarantee of free expression.

In the Supreme Court’s 4-3 Keegstra decision, Dickson upheld the provision. He concluded that Keegstra’s hateful speech caused two harms: first, “harm to the target group” because it causes them “grave” emotional damage; second, “society at large” by causing racial, ethnic and religious tension that may lead to discrimination and violence. Keegstra had not engaged in any incitement to harm or violence. But Dickson agreed with submissions from the Crown that people cannot be trusted to think rationally, or at least not as rationally as lawmakers and judges. In other words, he drew a straight line from Keegstra’s (obviously awful) views to recipients of those views experiencing or causing measurable harm. Dickson approvingly quoted the 1966 report of the Special Committee on Hate Propaganda, prepared by a group of law professors including Pierre Elliott Trudeau, which had recommended outlawing hate speech because individuals can be persuaded to believe “almost anything”.

In her lengthy dissent with two other justices concurring, Justice Beverley McLachlin came to the correct conclusion: the Criminal Code’s hate speech provision was unconstitutional. Channelling Mill, she pointed out that it “does not merely regulate the form or tone of expression – it strikes directly at its content and at the viewpoints of individuals.” McLachlin wrote that, “an infringement of this seriousness can only be justified by a countervailing state interest of the most compelling nature.” Although she did not adopt the golden rule or explain what kind of “countervailing state interest” is compelling enough to limit expression, she was clear that hateful words alone ought not be outlawed. McLachlin suggested it was irrational to believe that criminalizing hateful speech would stop it. Pre-Nazi Germany, she pointed out, had hate speech laws.

McLachlin was also concerned that the subjectivity of what counts as “hatred” made it so difficult to define that any such prohibition would deter some people from speaking at all. “The combination of overbreadth and criminalization may well lead people desirous of avoiding even the slightest brush with the criminal law to protect themselves in the best way they can – by confining their expression to non-controversial matters,” she wrote. The future Chief Justice’s remarks proved prophetic, for that is precisely the politically correct and, later, woke Canada we ended up in.

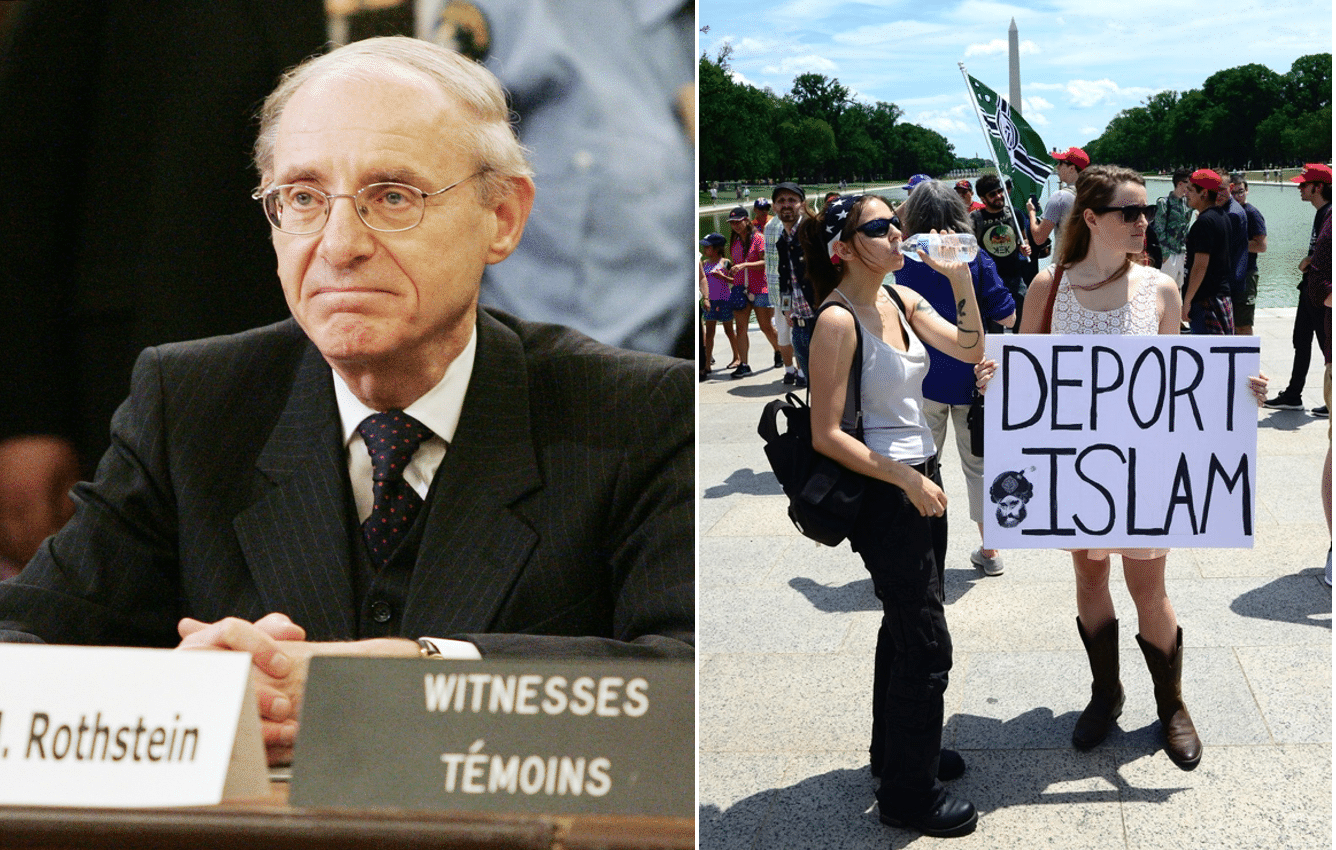

Supreme Court Justice Rothstein appeared to raise the bar – before lowering it back down. He wrote that speech that is merely ‘disdainful’ or ‘repugnant,’ that betrays ‘dislike,’ ‘discredits,’ ‘humiliates,’ ‘offends,’ ‘hurts feelings’ or causes ‘emotional reactions’ in a person or group, without more, cannot be outlawed.

Dickson offered his response to the question of whether “hatred” can be defined without “chilling” too much speech in a second monumental decision released that same day: Taylor. The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal had found neo-Nazi John Taylor guilty of contravening section 13(1) of the Canadian Human Rights Act forbidding communications “likely to expose” members of an identifiable group to “hatred or contempt.” Taylor had a disturbing habit of distributing cards inviting people to call a number where they would hear recorded messages denigrating Jews. This led to a prison sentence. According to Dickson, the words “hatred and contempt” were not so subjective that they would chill legitimate speech. They referred, he wrote, only to “unusually strong and deep felt emotions of detestation, calumny and vilification.” So the law was OK, and so was Taylor’s prison sentence.

Sifting through the Jurisprudential Wreckage

But how can anyone know whether their words count as protected expression that is merely “unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream” (Dickson in Irwin Toy) rather than the things Dickson now described that could land them in jail: “detestation, calumny and vilification”? It was only a matter of time before the courts would be asked to answer that question. In 2013, the Supreme Court revisited that fuzzy definition of hatred in Whatcott. In a 6-0 decision, Justice Marshall Rothstein upheld part of Saskatchewan’s Human Rights Code that banned publication or display of any representation “that exposes or tends to expose to hatred, ridicules, belittles or otherwise affronts the dignity of any person or class of persons on the basis of a prohibited ground.” But the decision didn’t do much to clarify the line between what can and cannot be limited.

Still no clear line of separation: In 2013’s Whatcott, Justice Marshall Rothstein (left) upheld banning “hatred”, understood as “extreme manifestations of the emotion described by the words ‘detestation’ and ‘vilification’,” yet legalized speech that “ridicules, belittles or otherwise affronts the dignity.” (Sources of photos: (left) CP Photo/Fred Chartrand; (right) Stephen D. Melkisethian, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Still no clear line of separation: In 2013’s Whatcott, Justice Marshall Rothstein (left) upheld banning “hatred”, understood as “extreme manifestations of the emotion described by the words ‘detestation’ and ‘vilification’,” yet legalized speech that “ridicules, belittles or otherwise affronts the dignity.” (Sources of photos: (left) CP Photo/Fred Chartrand; (right) Stephen D. Melkisethian, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)Rothstein appeared to raise the bar – before lowering it back down. He wrote that speech that is merely “disdainful” or “repugnant,” that betrays “dislike,” “discredits,” “humiliates,” “offends,” “hurts feelings” or causes “emotional reactions” in a person or group, without more, cannot be outlawed. People are even free to “debate or speak out against the rights or characteristics of vulnerable groups.” In a society that cares about free expression, he explained, hatred can be banished, but the definition must be limited to those “extreme manifestations of the emotion described by the words ‘detestation’ and ‘vilification’.” Rothstein reasoned that “this filters out expression which, while repugnant and offensive, does not incite the level of abhorrence, delegitimization and rejection that risks causing discrimination or other harmful effects.” So he struck down the part of Saskatchewan’s Human Rights Code that banned speech that “ridicules, belittles or otherwise affronts the dignity,” while upholding the part that banned “hatred.”

How do you differentiate between speech that “ridicules” and speech that “vilifies?” How do you know when your speech is “detestation” rather than mere “dislike”? Rothstein said one must look for the “hallmarks of hatred.” These include “blaming [a group’s] members for the current problems in society,” alleging they are a “powerful menace,” saying they are “carrying out secret conspiracies to gain global control,” saying they’re “plotting to destroy western civilization,” suggesting a group’s members are “illegal or unlawful,” labelling them “liars, cheats, criminals and thugs,” a “parasitic race” or “pure evil,” “equat[ing] the targeted group with groups traditionally reviled in society, such as child abusers [or] pedophiles,” or describing a group’s members as “horrible creatures who ought not to be allowed to live” or as “subhuman filth.” Is that all clear for you now?

How can a constitution that protects freedom of expression “so as to ensure that everyone can manifest their thoughts, opinions, beliefs, indeed all expressions of the heart and mind, however unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream” (as Dickson wrote in Irwin Toy) outlaw these kinds of comments? How can we exchange truth for error if we can’t allege without risking severe punishment that an extremist religious group is “plotting to destroy western civilization,” that people who advocate for medically transitioning kids are like “child abusers,” or that people from a certain country are more likely to commit crimes?

Still, Rothstein’s judgment was useful in drawing attention to one major issue: if governments can’t outlaw speech that merely “ridicules, belittles or otherwise affronts the dignity” of a person or group, then how can the many human rights tribunal decisions predicated on policing and punishing exactly that sort of offensive but not hateful speech possibly be constitutional? In 2021, the Supreme Court was forced to consider that conundrum in Ward.

The Human Rights Tribunal of Quebec had ordered comedian Mike Ward to pay $42,000 in personal restitution for telling jokes about a famous disabled teenage singer and his mother. In a 5-4 decision co-authored by Chief Justice Richard Wagner and Justice Suzanne Côté, the Court overturned the tribunal. The majority reiterated that there is no right “not to be offended” in free societies, that freedom of expression protects “unpopular, offensive or repugnant” speech, and that protecting a victim’s “emotional serenity” is not a reason to limit speech. They held that limits on freedom of expression are justified when the speech meets the definition of “hatred” set out in Whatcott or forces people “to argue for their basic humanity or social standing, as a precondition to participating in the deliberative aspects of our democracy.” While this sounds like a higher bar than Rothstein’s, it is still not entirely clear.

What justification was given for cancelling the concerts of American Christian singer Sean Feucht in the summer of 2025?

In late July 2025, Parks Canada cancelled a permit for Christian singer Sean Feucht to perform at the York Redoubt National Historic Site in Nova Scotia. The federal agency rationalized this act of censorship by citing concerns about “potential impacts to community members” and “heightened public safety concerns,” although it provided no evidence for its claims.

Following this, other municipalities also cancelled Feucht’s performances. The spokesperson for Montreal Mayor Valerie Plante, for instance, stated that the singer “goes against the values of inclusion, solidarity and respect” and that “hateful and discriminatory speech is not accepted in Montreal.” Feucht’s controversial views include calling the Black Lives Matter movement a “fraud”, stating that supporters of Pride Month have a “demonic agenda”, and criticizing abortion. At least six of Feucht’s performances were cancelled across Canada, although concerts went ahead in Edmonton, Alberta and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

The Principled – and Available – Alternative

Much of the past four-plus decades of confusion might have been avoided had Canada’s courts stuck to the clear and sensible jurisprudence they had developed in the pre-Charter era. But their lack of a principled line defining when speech can be legally restricted made it easy for organizations across Canada to cancel Feucht. While his concerts were greenlighted in Saskatoon and Edmonton and went ahead before joyous crowds and minimal disturbance from small bands of protesters last Thursday and Friday, respectively, these welcome victories for free speech still underscored the disquietingly arbitrary state of things.

Picture yourself as a mayor whose constituents are demanding you cancel Feucht – or some other controversial person or group. Canada’s top jurists have said free speech exists “so as to ensure that everyone can manifest their thoughts, opinions, beliefs…however unpopular, distasteful or contrary to the mainstream” and that there is no right “not to be offended.” They’ve said that speech that is “repugnant” or that “discredits” or “humiliates” a person or group is protected. The courts have also said alleging that a group is “plotting to destroy western civilization” or comprises “child abusers or pedophiles” are “hallmarks of hatred” – which can be criminalized. Even, presumably, if it’s true. (It is noteworthy that none of the critiques of Feucht that I’ve seen have engaged substantively with his specific views or based their position on whether what he is saying is true.)

What are you to do? The correct answer is to apply the latest test, from Ward, but even that is easier said than done. While Ward is clearly an improvement on previous caselaw, does anyone know exactly what speech will “force certain persons to argue for their basic humanity or social standing,” which would render it unlawful and possibly criminal? Certainly, you’ll find LGBT people who will assert that Feucht’s views betray such “hallmarks of hatred”.

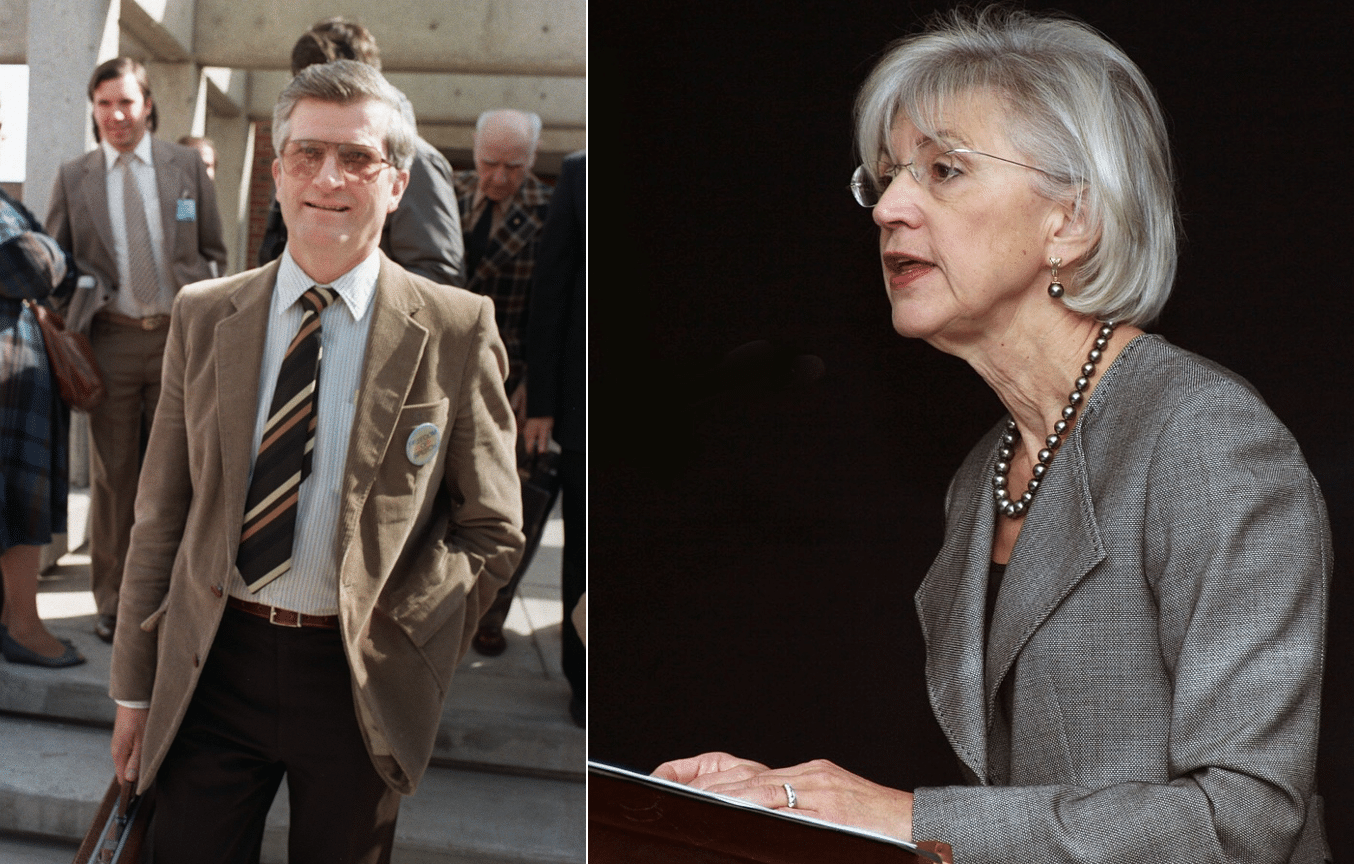

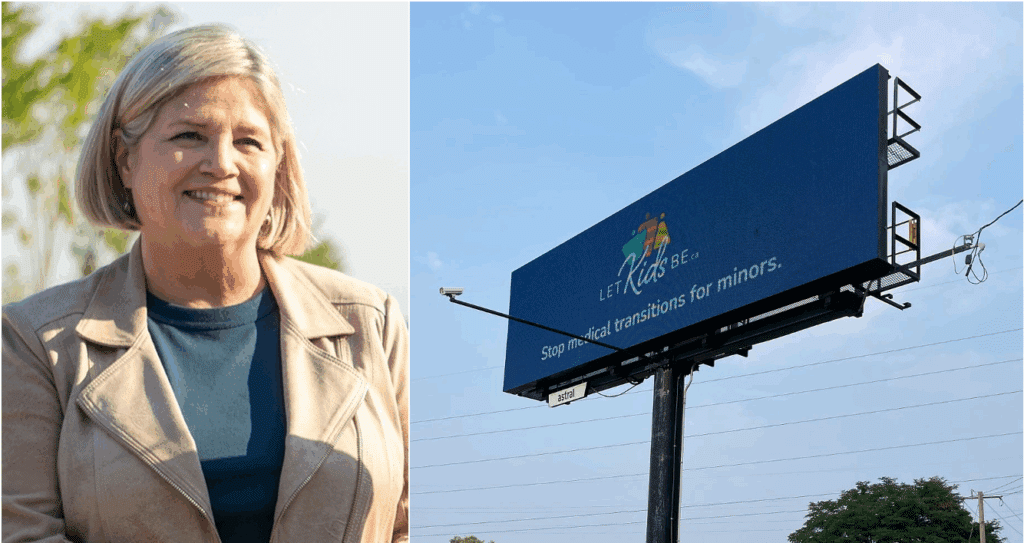

Mainstream opinion as “hate”: In Hamilton, Ontario, Mayor Andrea Horwath ordered removal of a billboard urging an end to sex-change operations for minors, triggering a Charter challenge. (Sources of photos: (left) Joey Coleman, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; (right) Juno News)

Mainstream opinion as “hate”: In Hamilton, Ontario, Mayor Andrea Horwath ordered removal of a billboard urging an end to sex-change operations for minors, triggering a Charter challenge. (Sources of photos: (left) Joey Coleman, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; (right) Juno News)As a free speech lawyer, I doubt most judges would find Feucht’s comments meet the high bar for limiting speech, and almost certainly not for barring him from speaking in advance. And yet one could still see some court somewhere finding that he is engaged in hate speech. His “millstones” comment may come very close. The Supreme Court addressed that type of comment in Whatcott, the previously mentioned Matthew 18:6 being the passage scrawled across a copy of a gay newspaper. Rothstein found that was not hate speech – although some of Whatcott’s other comments were. It took a trip to the Supreme Court to figure that out.

Murray Harbour, P.E.I., tried to remove village Councillor John Robertson for posting a sign in his yard that read: ‘Truth: Mass Grave Hoax. Reconciliation: Redeem Sir John A’s Integrity.’ Meanwhile Whitehorse, Yukon banned ‘microaggressions’ and wearing ‘disrespectful’ messages on buttons and shirts in council meetings.

Even if one is inclined to shrug off the Feucht brouhaha as an odd case that’s best forgotten, Feucht isn’t a unique situation, merely this summer’s most heavily covered one. Municipal officials across Canada seem to have forgotten that free speech exists. Barely two weeks ago, Hamilton Mayor and former Ontario NDP Leader Andrea Horwath ordered a billboard removed that argues against allowing minors to have sex reassignment surgery. Horwath likened to “hate” a widely held, indeed mainstream, opinion and something that happens to be official policy in dozens of U.S. states, many countries around the world and the province of Alberta. The Association for Reformed Political Action, which commissioned the billboard, is mounting a Charter challenge to the removal.

Municipal censorship laws have been flying out of council chambers faster than the civil liberties charity that I work for can respond. In 2023, Calgary passed a bylaw in response to protests against an event known as Drag Queen Story Hour that – rather than creating fines for impeding access, nuisance noise levels or harassment – outlaws any “expression of objection or disapproval towards an idea or action related to” race, gender and other human rights grounds within 100 metres of libraries.

That same year Murray Harbour, P.E.I. tried to remove village Councillor John Robertson for posting a sign in his yard that read: “Truth: Mass Grave Hoax. Reconciliation: Redeem Sir John A’s Integrity.” Meanwhile Whitehorse, Yukon banned “microaggressions” and wearing “disrespectful” messages on buttons and shirts in council meetings, until our organization stepped in. And last month we launched a challenge against the City of Niagara Falls after women were arrested for silently holding signs in council chambers that said “The Women of Ontario Say No.”

Had the Dickson court recognized Mill’s principle – that ideas must never be censored but that preventing harmful forms or imminent physical consequences of speech can be justifiably limited – we wouldn’t need to keep having these fights. And few of us would even know the name Sean Feucht.

Josh Dehaas is Counsel with the Canadian Constitution Foundation and co-host of the Not Reserving Judgment podcast.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.