We have all grown sadly accustomed to the misuse of language, especially legal and military language, to denigrate legitimate political engagement. We see open debate labelled as hate speech, defensive national policies deliberately confused with genocide, political action disparaged in the name of identity-infused human rights. In doing so, we diminish the seriousness of genuine violence, we undermine collective political action, we make a mockery of justice – and we prevent difficult and contentious topics from being debated freely.

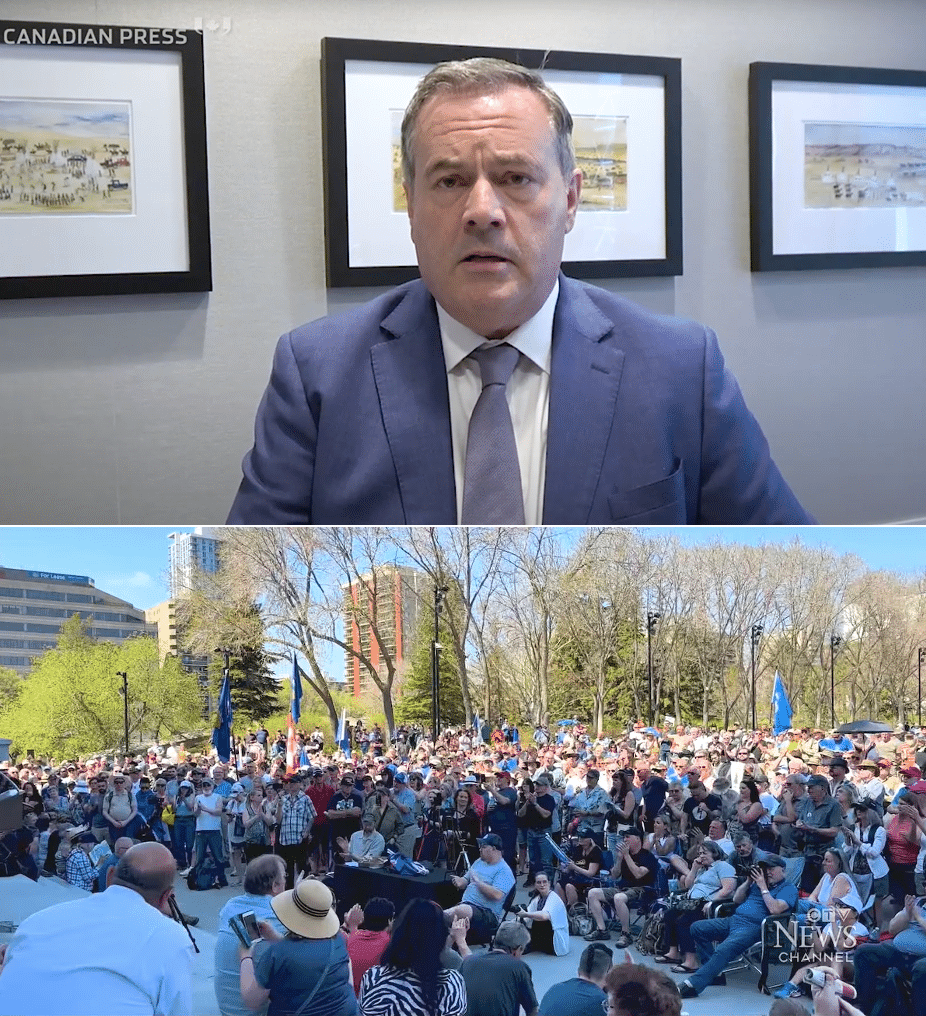

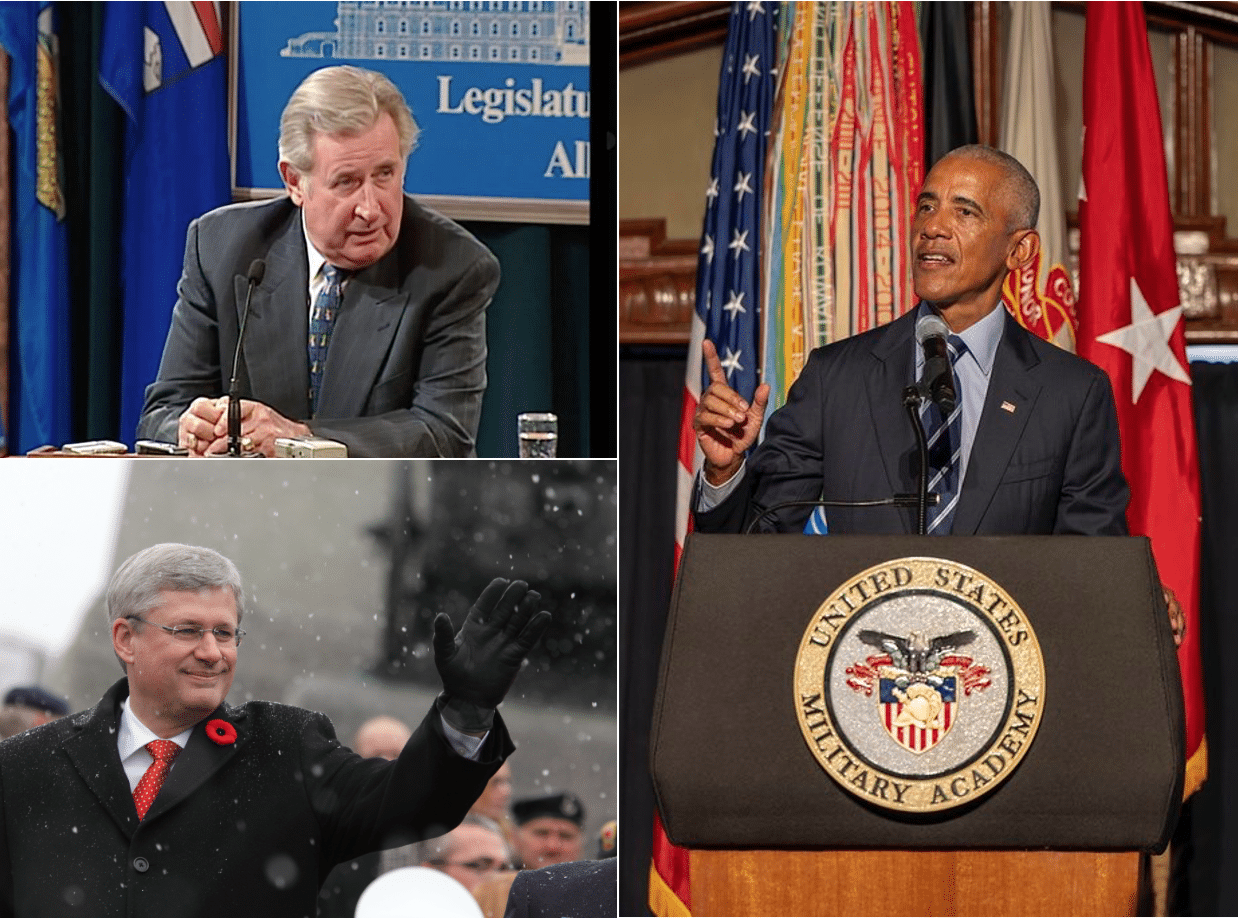

I was reminded of this when former Alberta Premier and Stephen Harper-era federal cabinet minister Jason Kenney once again came out of the corporate woodwork where he is currently earning his living to offer his thoughts on the unspeakable horrors that await Alberta should the province entertain a debate (perhaps even call a referendum) on separating from Canada. Holding forth from the boardroom of Bennett Jones, one of Calgary’s oldest and most storied law firms, Kenney served up an assessment of Alberta’s separatist forces that was equal parts untethered hyperbole and embellished fantasy.

On the one hand, Kenney dismissed Alberta’s separatists as a “perennially angry minority” consisting of “at most a few thousand people.” On the other, he claimed this tiny cabal not only threatens the unity of Canada but is about to tear apart the very fabric of society. Holding a vote on separation, declared Kenney, “would divide families, divide communities, divide friends for no useful purpose.” So “explosive” will be its effects that “marriages will break up over it” and “there will be businesses where partnerships break up.” There will even be “churches and community organizations that break up over this.” The “breaking” and “dividing” of institutions by a few thousand people will be rampant from one end of our 5-million-strong province to the other, “shredding the social fabric of the province [that separatism] purports to champion.” I briefly wondered why Kenney didn’t invoke the Spanish and Greek civil wars to dispel any doubt about what is coming.

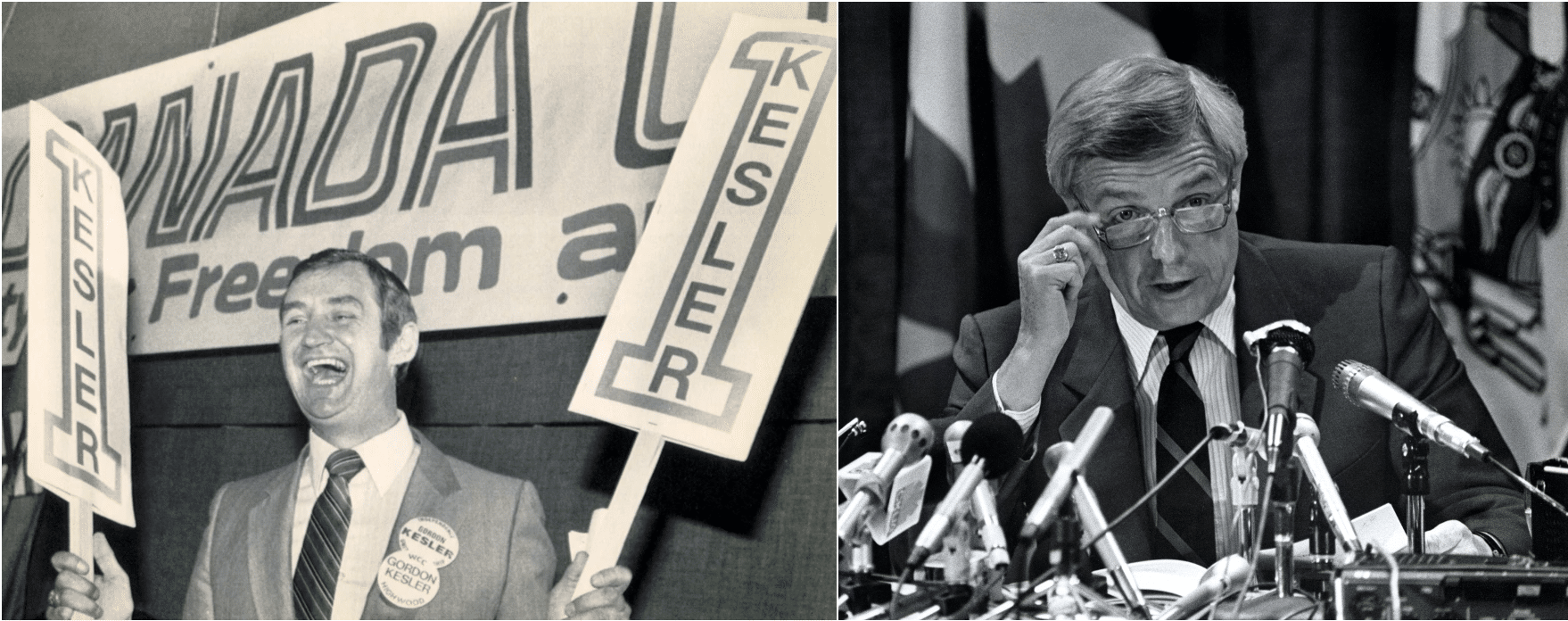

One might wonder how such an insignificant cadre of would-be revolutionaries could achieve such a world-rending impact here in Wild Rose Country. Kenney obligingly shed light on the history of the malcontents. Separation, he intoned, is a 50-year-old “discredited concept” whose acolytes “couldn’t get elected dogcatcher in this province.” Exhibit A in his analysis was Gordon Kesler, an Alberta rodeo rider and oil company scout who concluded that independence was the only way to save Alberta and the other Western provinces from the depredations of Ottawa. In a 1982 byelection, Kesler got himself very much elected to the Alberta Legislature under the Western Canada Concept banner.

Although Kesler soundly lost his seat in the general election held just a few months later, he lost to the Progressive Conservative Party led by Peter Lougheed, an immensely talented politician at the top of his game and the peak of his popularity, who specifically asked Albertans for a mandate to more effectively resist Ottawa. Far from dividing Albertans, the whole episode brought us closer together. Lougheed, coincidentally, long practised law at Bennett Jones, Kenney’s current home, and managed to defeat his opponents without attempting to humiliate every single Albertan who might have entertained similar thoughts to Kesler’s.

Kenney, though, just can’t help himself. He paints those who would now attempt to leave Canada through a democratic vote as followers of Vladimir Putin and (perhaps even worse?) Donald Trump. “[I]f you just follow them on social media,” he claimed, one will quickly see that they cheered on Putin’s attack on Ukraine and Trump’s threat of making Canada the 51st state. I have to admit that I do not scour TikTok for deep insights from Alberta separatists into centuries-old Russian imperial policy. It did occur to me, though, that Putin’s Russia is trying to prevent the independence of a smaller democracy that was once part of the Soviet empire.

Differences of opinion and outlook are innately human. We can’t wish them away or, as Kenney appears fond of attempting, stamp them out. Even seen purely as a political tactic it doesn’t seem very effective, as he should well know. As premier from 2019 until late 2022, Kenney became a divisive figure who couldn’t resist stoking divisions.

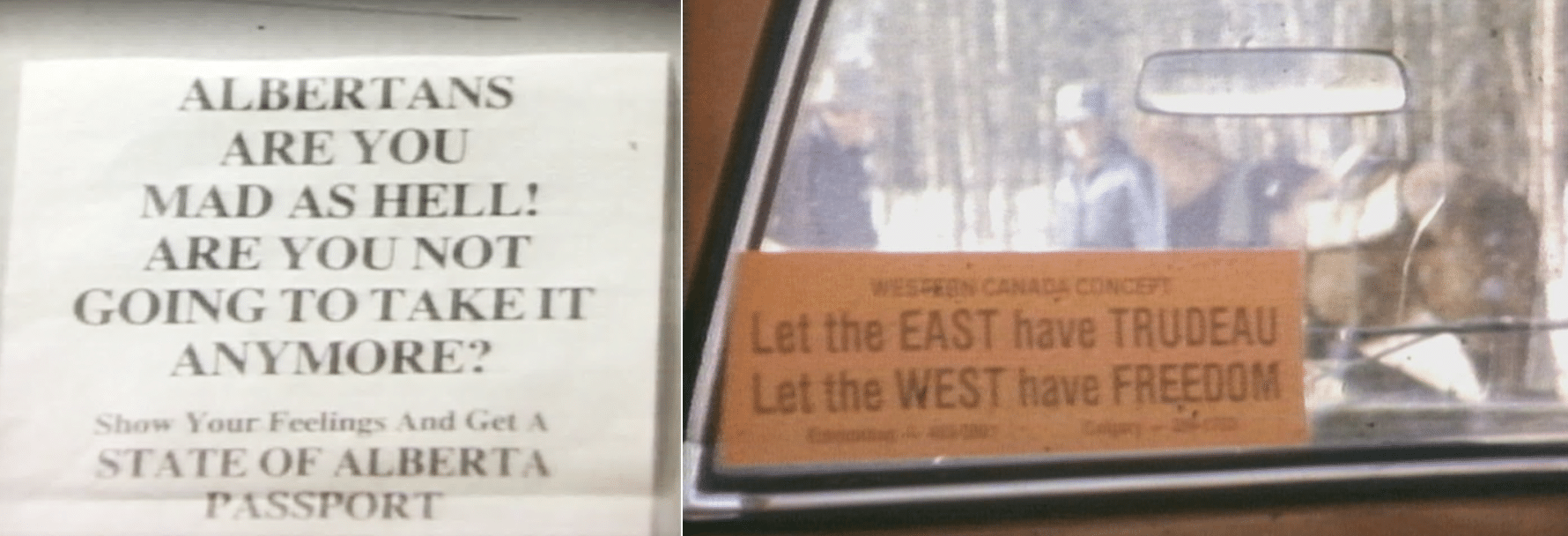

As a born and bred Albertan, I, unlike Kenney, lived in the province when Kesler won his byelection and talk of separation was all the rage. Everyone talked about it, thought about it, argued over its obvious risks and potential benefits, and laughed about it. Yet couples were not running to their divorce lawyers over it, business partners were not at each other’s throats, neighbours were not vandalizing one another’s flowerbeds or letting the air out of each other’s car tires at night, and churches were not excommunicating separatists for political nonconformism. Alberta was not on the precipice of anarchy and societal demise. People were angry at Ottawa and convinced that something needed to be done. That all sounds rather familiar today.

What is former Premier Jason Kenney’s argument against holding a referendum on Alberta separation?

Jason Kenney characterizes supporters of Alberta separatism as a “perennially angry minority” of a few thousand people. He argues that despite these small numbers, a referendum on the issue would be so “explosive” it would shred the province’s social fabric. Holding such a vote would “divide families, divide communities, divide friends for no useful purpose,” he says. Business partnerships and even churches and community organizations would break up. He also portrays those who support leaving Canada through a democratic vote as followers of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump.

So why all this sound and fury, signifying remarkably little? For a – let’s give credit where credit is due – highly successful politician who won multiple elections and served ably as a senior Harper minister and later as premier during a very difficult period, Kenney shows a curious lack of awareness regarding the role of democracy. Democracy isn’t about hiding divisions and preventing difficult issues from being put to the vote. It’s about deciding difficult issues by putting them to a vote, either directly through plebiscites and referenda or indirectly through general elections.

Differences of opinion and outlook are innately human. We can’t wish them away or, as Kenney appears fond of attempting, stamp them out. Even seen purely as a political tactic it doesn’t seem very effective, as he should well know. As premier from 2019 until late 2022, Kenney became a divisive figure who couldn’t resist stoking divisions. He did so repeatedly during the Covid-19 pandemic, alienating one political demographic after another by treating their views and concerns with contempt. His most recent remarks, then, are not a rare and considered intervention at an hour of peril but are of a piece with his propensity to angrily lash out at opponents.

Indeed, I believe the personal element was the main driver. Kenney has made it clear he perceives his toppling as United Conservative Party leader to be the result of a Trumpian-inspired or “MAGA” campaign, which he conflates with Alberta separatism and, in turn, anyone who strenuously opposed the official government narrative on Covid-19, especially mandatory vaccination. Commenting on his removal in May 2022, he said, “I think the energy in the no vote was primarily driven by people angry about vaccines, and I make no apology for promoting safe and effective vaccines that saved lives.” UCP party faithful, however, said their rejection of him had far more to do with his top-down leadership style and habit of “blaming other people for the errors he made.” However small that (alleged) separatist faction may be, it proved potent enough to topple Kenney in his adopted province.

Is separatism a new idea in Alberta politics?

Alberta separatism has a long history in the province, a product of Western alienation and the imbalance in Canada’s political institutions that concentrates power in southern Ontario and Quebec. In a 1982 byelection, Gordon Kesler, a rodeo rider and oil company scout, was elected to the Alberta Legislature representing the Western Canada Concept party, which argued independence was the only way to save Alberta and the other Western provinces from the depredations of Ottawa. Although Kesler lost his seat in the general election a few months later, he was defeated by the Progressive Conservative Party led by Premier Peter Lougheed. Lougheed had specifically campaigned for a mandate to more effectively resist Ottawa.

What especially strikes me about Kenney’s separatist obsession is that he seems to understand as little about Albertans now as he did while premier. Kenney both underestimates and mischaracterizes the long-simmering discontent among Albertans. But Albertans are not fragile dolls unable to engage in serious conversations about the future of their province or their role in Canada. The social fabric will not tear apart under the pressure of discussions, or even a vote, on separation.

Beyond Kenney’s personal disdain, there are legitimate reasons for concern about Canada’s social and political structure, as well as the role provinces play in that structure. Canada’s institutions operate largely on an old colonial model that concentrates power in the original population centres of southern Ontario and Quebec. Unlike the United States with its multiple, geographically dispersed population hubs that include not only the original Northeast but California, Texas, Florida, the Rocky Mountains and the Midwest, and which provide equal representation in the U.S. Senate, Canada’s institutions from Parliament to the Supreme Court are still dominated by the metropolitan conglomeration running from Quebec City to Windsor. This has not, and does not, make for great national cohesion or political participation. Instead, it feeds constant fuel to separatist fires.

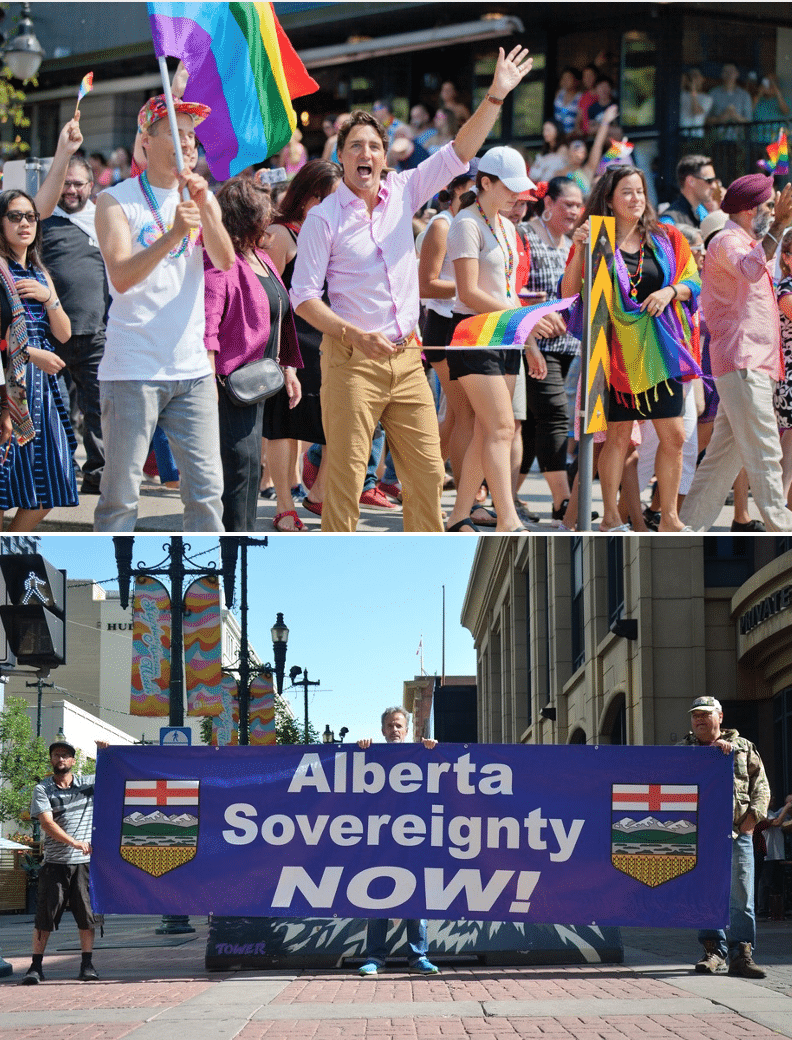

The current threat to Canadian identity does not come merely from our unbalanced institutional arrangements but increasingly from our ideological commitments, especially those of our federal government. Early in his time as Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau declared Canada to be a “post-national” nation. This sort of moniker is consistent with the popularly-designated woke doctrine that eschews the liberal nation-state, democratic procedures and individual freedom in favour of tribalist narratives, identity politics, the Marxist oppressor-oppressed doctrine and disciplinary administrative processes.

The obsession with post-nation-state policies has, in my opinion, initiated the dissolution of the Canadian nation regardless of whether Quebeckers or Albertans actually vote for separation. We are all becoming de facto separatists within a dissolving Canada, a drift that current Prime Minister Mark Carney’s ineffective “elbows up” attitude has done nothing to reverse.

If Jason Kenney were to ask me, and I know he won’t, I would tell him that, as someone with a long Alberta pedigree and as a descendant of both American founders and Volga Germans from Russian Saratov and Ukrainian Odessa, I’m confident Alberta is not so fragile that a referendum on separation will plunge the province into civil war.

Kenney’s panicked musings about Alberta separatists would have us believe that Albertans, “frustrated with how the province is treated,” need only continue the fight for a better deal within the Canadian federation. Kenney pursued just such a policy, and failed signally to deliver. For too many Albertans today, his advice does not reflect the political reality on the ground nor appreciate the worrying trends within Canadian institutions and among our political class.

What are the key structural and ideological factors contributing to discontent in Alberta?

Legitimate concerns about Canada’s political structure fuel Western alienation. The country’s institutions operate on an old colonial model that concentrates power in the population centres of southern Ontario and Quebec. Unlike the United States, which has geographically dispersed population hubs and equal state representation in the U.S. Senate, Canada’s Parliament and Supreme Court are dominated by the metropolitan conglomeration running from Quebec City to Windsor, which hinders national cohesion. As well, the ideological commitment of the federal government to the idea that Canada is a “post-national” state – a kind of woke doctrine that eschews democratic procedures and individual freedom in favour of tribalist narratives and identity politics – has the effect of weakening national identity. Canadians are all, in a sense, becoming de facto separatists within a dissolving Canada.

Kenney often casts himself as a “principled conservative”, associating his views with those of Edmund Burke, the father of modern conservatism, while touting his own ancestry among United Empire Loyalists – those British colonists who rejected the American Revolution and resettled in Canada. He clearly feels we must defend our institutions of ancient origin against the post-national menace. While I agree with Kenney about the threat, it is not clear that a simple conservative return to our celebrated institutions – even if such a thing could be engineered – would overcome our contemporary malaise.

If he were to ask me, and I know he won’t, I would tell him that, as someone with a long Alberta pedigree and as a descendant of both American founders and Volga Germans from Russian Saratov and Ukrainian Odessa, I’m confident Alberta is not so fragile that a referendum on separation will plunge the province into civil war. Indeed, in his recent comments, Kenney mentions his plans to head to Ukraine to do charitable work with the Knights of Malta. In doing so, he will be entering into the theatre of a real war. While war may be the continuation of politics by other means, to quote the German military theorist Carl Von Clausewitz, war is not politics itself – those “other means” define a wholly distinct human occupation.

I would suggest to Kenney that his remarks do not help to restore sanity to Alberta politics. Instead, they muddy the already murky waters of our contemporary political confusion. I would also remind Kenney that his hero – Edmund Burke – was known as much in his day for his sympathies with the American revolutionaries and their creation of an experimental new republic as he was for his contempt towards the French Revolution and its awful Reign of Terror. This reflects the fact that Burke’s conservatism still linked real actions with true words. It would be advisable, perhaps, to keep our own political language here in Alberta within the bounds of the plausible rather than fly off into the fanciful.

Collin May is a lawyer, adjunct lecturer in community health sciences with the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, and the author of a number of articles and reviews on the psychology, social theory and philosophy of cancel culture.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.