It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.

—Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

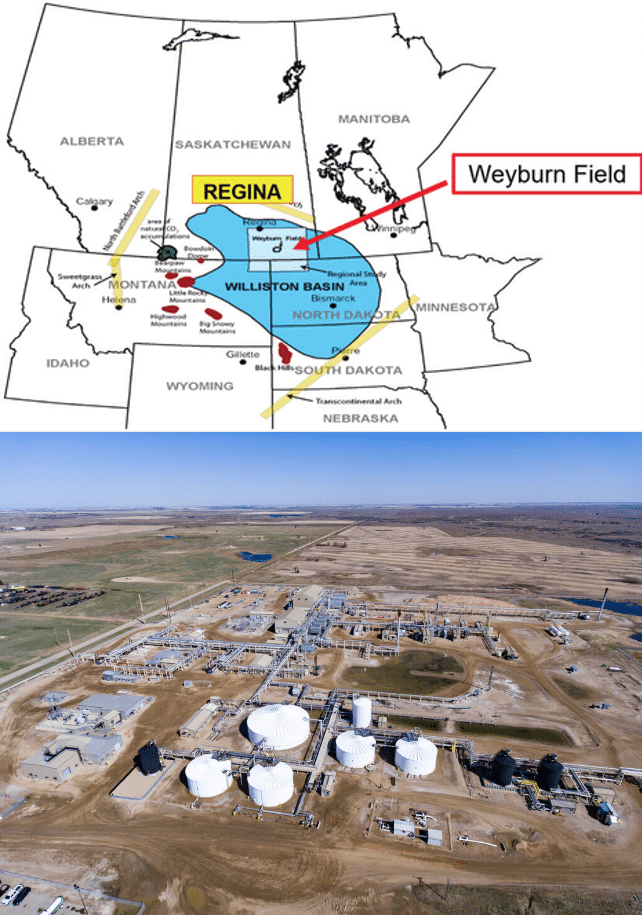

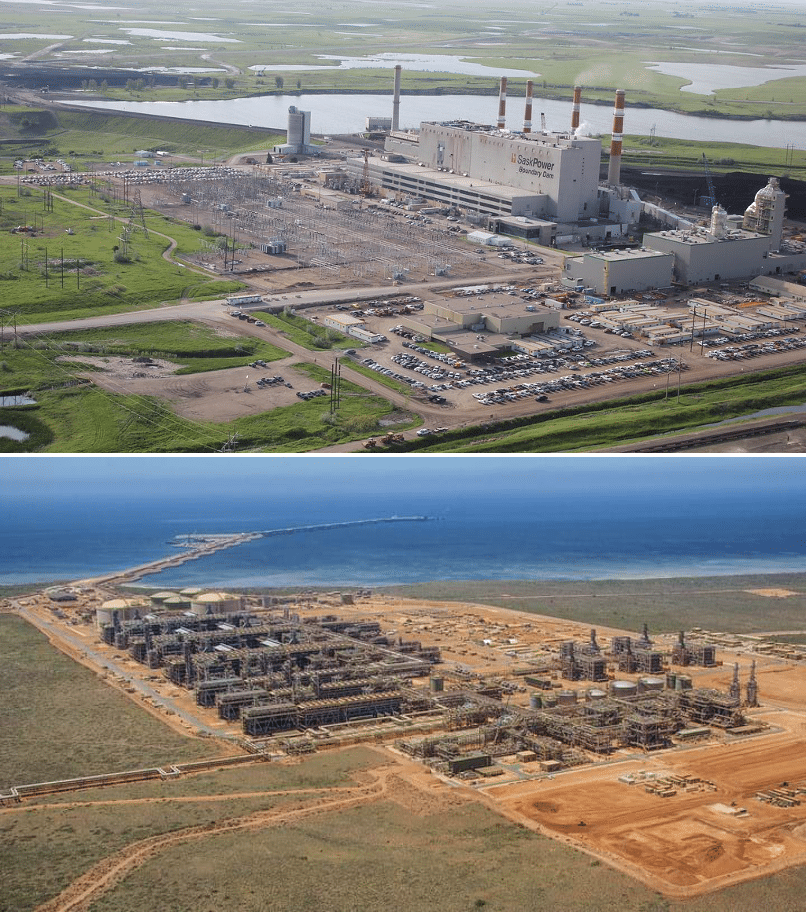

Near the southern Saskatchewan city of Weyburn, the land is flat, the sky vast and the pump-jacks a familiar token of Western Canadian energy-based prosperity. What makes the fields outside town extraordinary, however, is not the crude oil being pumped out of the ground but what is pumped back into it. For more than 25 years, this corner of the Prairies has been the site of one of the world’s longest-running experiments in the capture and underground sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2).

From the coal-fired Great Plains Synfuels Plant near Beulah, North Dakota, a 320-km-long pipeline delivers liquefied CO2 recovered from the plant’s exhaust stream to Weyburn. There, massive pumps force it deep underground and inject it into a largely depleted oil reservoir. The added pressure pushes out additional quantities of the stubbornly situated crude even as the injected CO2 remains trapped in the rock. Since 2000, the Weyburn Carbon Capture, Utilization and Sequestration Project has produced more than 104 million incremental barrels of light, sweet (low-sulphur) oil. While it’s not a huge money-maker, each year it also sequesters underground approximately 1.7 million tonnes of CO2 that would otherwise be vented.

And therein lies the connection to the Government of Canada’s fixation on reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Weyburn and similar projects in Alberta that use CO2 for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) have become showcases for something more ambitious than squeezing the last drop of oil out of a reservoir: the idea that oil itself can be “decarbonized”. That is, by capturing and burying an amount of CO2 equivalent to that generated in the production and processing of oil, the atmosphere ends up no more burdened by that particular greenhouse gas, and the goal of “net zero” becomes seemingly achievable even without scaling back Canada’s oil and natural gas production. Projects such as Weyburn therefore suggest the possibility of overcoming the dilemma of how to sustain Canada’s number-one source of export earnings while meeting national carbon-reduction targets.

Two essential questions arise. The first is whether what’s done at Weyburn can be scaled up sufficiently to decarbonize the approximately 1 million barrels per day of Alberta oil that it would take to satisfy three major interests at play. The province of Alberta is the first of the three interests. Faced as it is with a surging population and Premier Danielle Smith’s ambition to fortify the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund, Alberta’s oil and natural gas production simply must keep growing to generate jobs and the higher energy royalties critical to Smith’s plans to pay down Alberta’s public debt.

A new oil pipeline from Alberta to Prince Rupert, B.C., for example, could enable overall crude output to grow by an impressive 25 percent, increasing Canada’s annual export revenues by as much as $20 billion. Some of the resulting profits could in turn be directed to help finance major new carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. Just days ago, in fact, we learned that Alberta will submit a formal application to the federal Major Projects Office for a new pipeline to carry oil sands bitumen to B.C.’s northwest coast.

This is what Smith has termed the “grand bargain”: Alberta’s oil sands not only escape former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s goal of being “phased out” but, because the associated CO2 is stored rather than vented, continue to grow robustly. The province wins time and political space to keep its most important industry thriving. Federal authorities including their current champion, Prime Minister Mark Carney, can claim substantial progress on GHG emissions. Millions of ordinary Canadians are convinced the country is doing its bit to “fight climate change” without destroying the national economy. And the more radical environmentalists – including the Steven Guilbeault faction in Carney’s Liberal Party – are sidelined. CCS technology thus seemingly offers an all-purpose compromise that might moderate an otherwise fractious national debate over energy and climate policy. It all sounds amazing.

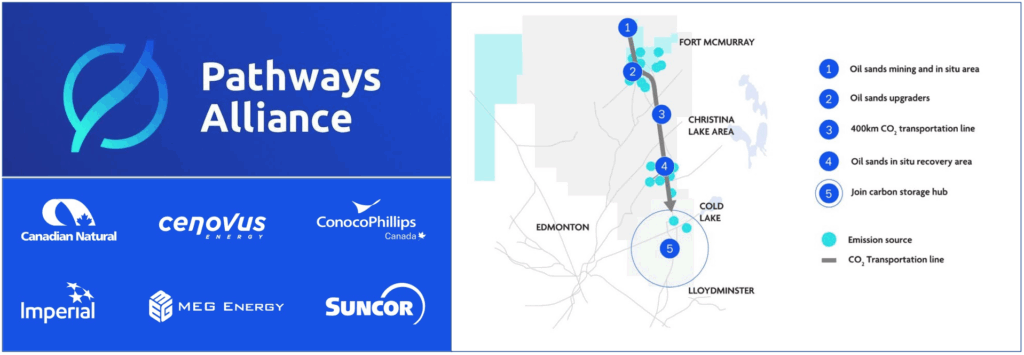

Key to the success of Smith’s grand bargain is the second of the third major interests: the Pathways Alliance CCS network. Pathways, whose six members generate 95 percent of Canada’s oil sands production, regards CCS on a grand scale as furnishing the “social licence” its members need to expand production. A gigantic undertaking with a current estimated cost of $16.5 billion, Pathways differs from the Weyburn model in that it will have no expectation of recovering and selling incremental oil. Forcing CO2 underground will be the sole objective and, hence, the entire project will impose a straight cost on its participants. The hope is that this cost will be worth it if it effectively purchases the right to vastly expand Alberta’s oil sands production.

What is decarbonized oil and how is it produced?

The concept of “decarbonized” oil involves capturing and burying an amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) equal to that generated in the production and processing of oil. The broader goal is to achieve “net zero” emissions without reducing Canada’s oil and natural gas production. This process relies on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology like that in use at the Weyburn Carbon Capture, Utilization and Sequestration Project in Saskatchewan, which sequesters underground approximately 1.7 million tonnes of CO2 every year. It is hoped that such technology could help the Alberta oil sands reduce greenhouse gas emissions on a massive scale.

The Pathways Alliance plan resembles the Weyburn model on a massively enlarged scale. It would reduce GHG emissions by capturing, compressing and transporting “process” CO2 in a liquefied state from up to 20 oil sands facilities in northern Alberta, through a 400-600-km-long pipeline, to a deep injection underground storage hub near Cold Lake, presumably to stay there in perpetuity. Phase 1 would sequester a planned 11 million tonnes of CO2 per year, with Phase 2 envisioned at nearly 40 million tonnes per year – an annual volume equivalent to what Weyburn does in about 23 years. Simple and neat in concept, Pathways faces steep technical challenges to execute.

Start with the process of capturing the CO2, which is a natural byproduct of combustion. (For example, when the simplest hydrocarbon, methane or natural gas (CH4), is combusted with oxygen (O2), the chemical result is water vapour (H2O) and CO2). One option is post-combustion capture, which uses chemical solvents to absorb the CO2 from the exhaust stream at the oil sands plant. Another is pre-combustion capture, whereby fuel is partially oxidized to separate CO2. A third method, oxy-fuel combustion, sees fuel burned in nearly pure oxygen, which reduces pollutants and creates a CO2-rich exhaust stream that is easier to capture. Each such method offers a mix of technical and economic benefits and challenges.

‘The world will more and more require decarbonized barrels and decarbonized forms of energy writ large,’ Pathways Alliance President Dilling predicts. ‘We actually think this can become a competitive advantage for Canadian heavy oil as we provide the most responsibly produced barrel of oil to global markets.’

The next challenge is moving the captured CO2 efficiently. The best way is to compress the gas into a supercritical fluid, which reduces its volume and solves other technical problems. This, however, requires massive, costly and energy-consuming multistage compressors with coolers designed to manage heat from the compression process. The CO2 gas becomes supercritical at approximately 150 times sea-level atmospheric pressure – and in this dense form can be pipelined to the downhole injection sites and onward into deep rock formations sealed by impermeable caprocks.

Western Canada’s energy industry was built on taking risks, committing capital and solving problems, and Pathways’ proponents are bullish that this all can be made to work. “The most important thing we can do in the near term is decarbonize the production of our product here in Canada,” says Pathways Alliance President Kendall Dilling. “That will help us provide that barrel to global markets in the most responsible way possible.” Far from just being a necessary evil, Dilling asserts, CCS could become the international marketing centrepiece for Canada’s oil industry. “The world will more and more require decarbonized barrels and decarbonized forms of energy writ large,” Dilling predicts. “We actually think this can become a competitive advantage for Canadian heavy oil as we provide the most responsibly produced barrel of oil to global markets.”

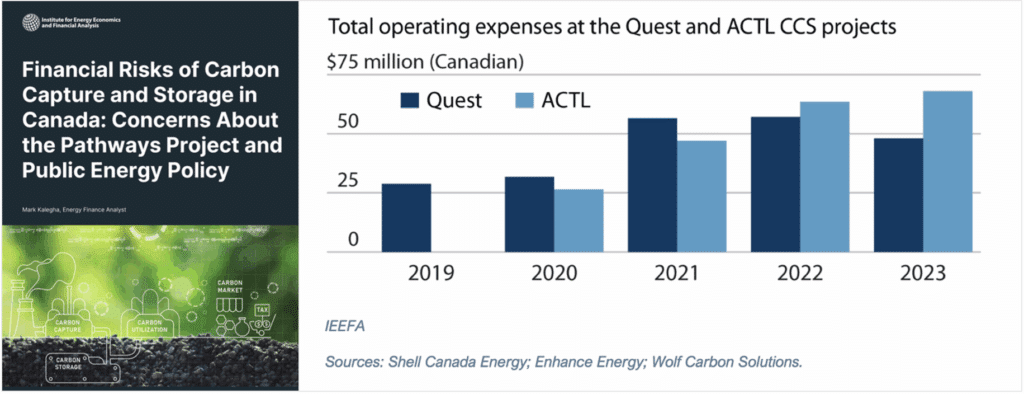

There are serious – and credible – doubters to all of this, however. One is the authoritative Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), which in a January 2025 paper concluded that rising operating costs, uncertain revenues, an oversupplied market for emission credits and stalled efforts to improve large-scale CCS technology could impede the entire plan. Another is widely published energy writer Jennifer Considine, who holds a PhD in economics and is Senior Research Fellow at Scotland’s Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy. “After three decades and billions in subsidies, carbon capture has produced little more than enhanced oil recovery revenues and high-profile failures,” Considine wrote just last month. “Projects like Boundary Dam and Petra Nova illustrate the problem: large losses for taxpayers, modest returns for operators and dependence on oil prices and subsidies.”

To other CCS skeptics, Exhibit A is the chronically underperforming Chevron Gorgon Project in Australia, the world’s largest operational CCS project, which last year captured only 30 percent of its targeted CO2 emissions, incurring a fearsome cost of US$222 per tonne captured. And while the dream of locking CO2 away for millennia may be compelling, the long-term storage of CO2 also comes with significant technological impediments. These include the uncertain geological stability of the injection sites and the need for constant monitoring to ensure the CO2 stays in place.

What is the Pathways Alliance and what are its objectives?

The Pathways Alliance is a coalition of six companies that together account for 95 percent of Canada’s oil sands production. Its plan is to build the capacity to capture, compress and transport CO2 in a liquefied state from up to 20 oil sands facilities in northern Alberta, through a 400-600-km-long pipeline, to a deep injection underground storage hub near Cold Lake, Alberta. Phase 1 would sequester 11 million tonnes of CO2 per year, with Phase 2 envisioned at nearly 40 million tonnes per year.

In return for the industry’s investment in such a large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) network, oil sands producers would gain the “social licence” needed to expand production and the federal government would see itself clear to approving a new oil pipeline for export. Alberta premier Danielle Smith has called this a “grand bargain”, though some say the idea is both unfair and unworkable.

As for the third major interest, the climate-obsessed Carney government, a functional CCS industry is being dangled as a green slip to define Western oil so-produced as “decarbonized”. Carney has hinted that his government would consider approving a new crude oil export pipeline to move the increased oil sands production the Pathways members seek. With Carney having promised through Bill C-5 (dubbed the One Canadian Economy Act) to advance major projects to get Canada’s lagging economy moving, not only Smith but millions of Albertans expect that new oil and natural gas projects will be among them. Indeed, a failure in that regard would be almost certain to re-ignite the flames of Alberta separatism.

And so CCS has come to represent more than geology or engineering. It is a symbol of how Canadian governments and industry are attempting to reconcile two seemingly contradictory imperatives: maintaining prosperity through oil production and demonstrating international good faith on emissions reductions. Many, like Dilling, see Canada as a global leader in CCS technologies, which they define as all measures that directly reduce emissions from heavy industries to help achieve net zero targets. It will need to be. Scalability is not the only serious challenge facing the Pathways Alliance.

The Pathways Alliance has so far spent $1.8 billion on preparatory studies and technology evaluations. This work has led to some estimates that the project would require total commitments of $24 billion before 2030. Such figures are daunting and probably account for the fact that even with announced policy commitments from governments for financial tax credit incentives designed to offset the project costs, substantive financial commitments for co-investment remain conditional and tentative. Aside from the monumental capital costs, there will be the ongoing operating costs for facilities designed to capture, compress, transport and inject the emissions, for which cost estimates and real-world benchmarks vary widely. So it is understandable that the Alliance would argue that tax credits are essential for the project’s economic viability. These issues are clearly material from a regulatory and financial perspective but, apparently, are as yet unquantified.

Even if Pathways’ physical processes ultimately prove workable, then, it’s far from clear that the numbers can be made to do so. As Chevron Inc.’s Gorgon boondoggle demonstrates, the financial burden imposed for huge, at-scale CCS projects like Pathways could be $200 or even $300 per tonne of captured CO2. Such profound doubts about the economic feasibility of large-scale CCS have raised fears that governments may yet find themselves called upon to directly fund these projects. As the IEEFA analysis cited above notes, these “troubling cost implications…[raise] the concern that the Canadian federal government and the province of Alberta may be pressured to make up the likely shortfall.”

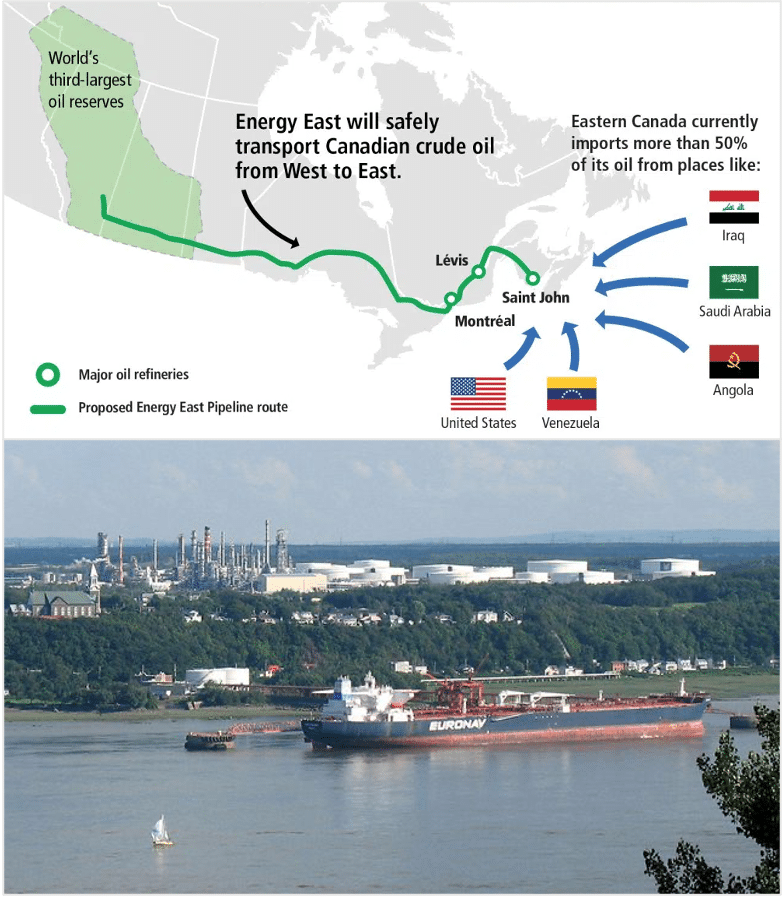

This might cause one to wonder whether Smith’s musings about a “grand bargain” are anything more than a back-of-the-envelope guesstimate conjuring a kind of political unicorn, a federally-approved export pipeline carrying hypothetically decarbonized oil. And this brings us to the second major question, one that stabs at the heart of the economies of Alberta and Saskatchewan: why is it important that Western Canada’s oil be “decarbonized” at all, when that requirement is not imposed upon oil imported to Eastern Canada, much of it from countries whose environmental standards are nowhere near as rigorous as those of Western Canada?

The obligation about to be imposed upon Western Canada’s energy sector to produce and transport ‘decarbonized’ oil will place it under a material – if not ruinous – regulatory and financial handicap in world markets. Meanwhile, Eastern Canadian refiners would be allowed to continue importing oil from the United States and offshore jurisdictions.

The term “decarbonized” is assuredly aimed directly – and solely – at Western Canadian oil production. So too is the federal government’s ongoing commitment to “responsibly produced oil and gas”, defined as a Canadian oil and natural gas emissions cap, the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act, a (now somewhat deferred) Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Mandate, a Clean Fuel Regulation and a Clean Electricity Standard (CES) ostensibly leading to a net-zero electricity grid by 2035 (recently deferred to 2050).

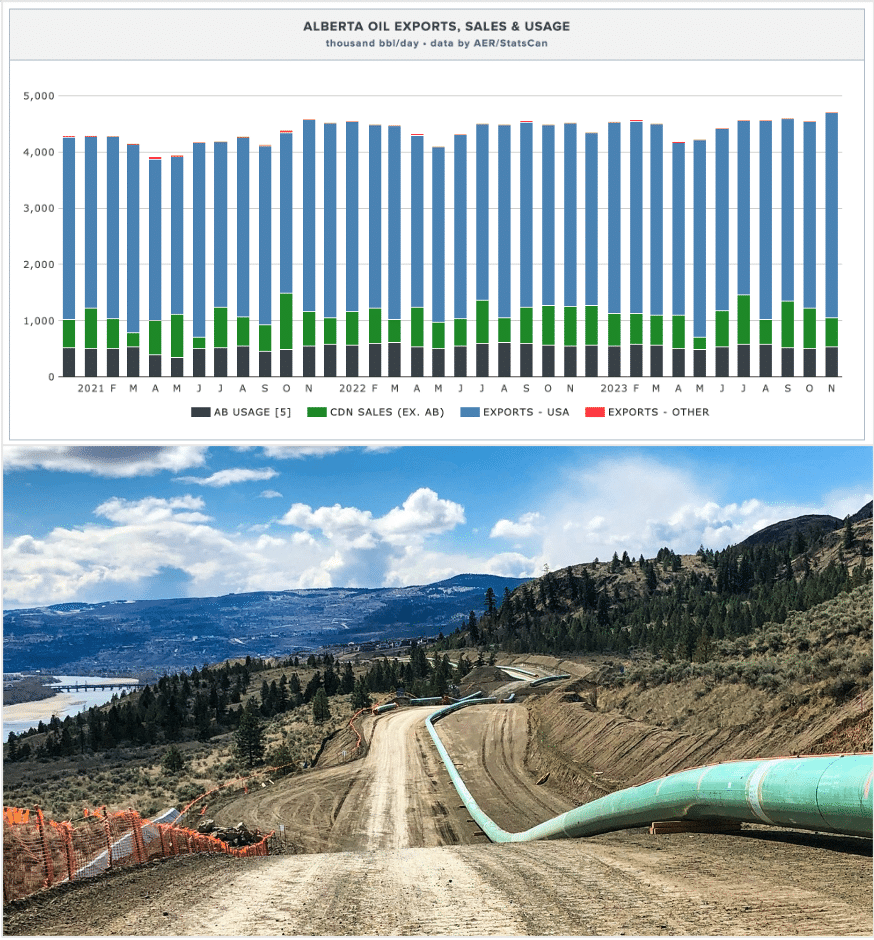

The Alberta oil sands currently generate 58 percent of Canada’s total oil output. Data from December 2023 shows Alberta producing a record 4.53 million barrels per day as major oil export pipelines including Trans Mountain, Keystone and the Enbridge Mainline operate near capacity. Meanwhile, in 2023 Eastern Canada imported on average about 490,000 barrels of crude oil per day by pipeline and sea. The region’s crude oil imports totalled $19.5 billion that year, sourced from the United States (72.4 percent), Nigeria (12.9 percent) and Saudi Arabia (10.7 percent). Since 1988, imports by marine terminals along the St. Lawrence River have exceeded $228 billion, while imports by New Brunswick’s Irving Oil Ltd. refinery totalled $136 billion from 1988 to 2020.

Self-evidently then, the obligation about to be imposed upon Western Canada’s energy sector to produce and transport “decarbonized” oil will place it under a material – if not ruinous – regulatory and financial handicap in world markets. Meanwhile, Eastern Canadian refiners would be allowed to continue importing oil from the United States and offshore jurisdictions, free from any comparable regulatory burden. Can the immense cost of capturing, transporting and storing CO2 be justified by the revenues from oil that is, by definition, largely made of carbon?

Investors appreciate that as with all complex regulatory and policy matters, the devil often lurks in the details. It may be no coincidence that the Canadian energy sector’s own investments have increasingly favoured other jurisdictions. Benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil is currently trading in the range of US$60-65 per barrel, and low-grade oil sands bitumen trades at a substantial discount to that. How much more can Canadians afford to penalize their own oil producers? What might be the consequences if oil prices fall below the current price range? And who will pay the ongoing, unavoidable operating costs for the machinery needed to compress the CO2 and force it into the underground storage formations?

It will not be crude oil markets that pay. It is simply a cost that Canada would impose on itself to reduce operating profits from exported oil (known in oil production economics as the “netback”, the key performance metric of how much profit a company makes per barrel of oil after subtracting all the costs required to bring that oil to market). The consequence of imposing that cost would certainly be a loss of market share not just for Alberta, but for Canada. None of Canada’s international heavy oil supply competitors are imposing such a cost, and no other country is paying it. Can Alberta, much less Canada, afford this?

Carney’s “decarbonized” oil proposition represents a commercial standard that may be difficult if not impossible for Alberta’s hydrocarbon production industry to achieve. It very much remains to be seen whether a concerted effort to bury CO2 to “decarbonize” Western Canadian oil will restore a much-diminished Canadian “can-do” spirit for economic development and encourage much-needed interprovincial teamwork across shared jurisdictions.

The politics of why the Liberal government appears to favour dividing the Canadian economy into two, with one part based on expensive domestic oil and the other on cheaper imports, is beyond the scope of this article. But of this we can be confident: by insisting that Western oil producers bury their CO2 at a still-unknown but surely enormous cost, the nascent “Carney doctrine” would effectively split Canada into two economic development zones – one based upon a “decarbonized” Western Canadian oil production zone and another that allows internationally-imported “fully carbonized” oil to enter Eastern Canada free of penalty.

Why is the Mark Carney government’s decarbonized oil policy unfair to Western Canada?

The policy is unfair because the obligation to produce and transport decarbonized oil will add a huge financial burden to Western Canadian oil production, making it uncompetitive even if the technology proves feasible. At the same time, refiners in Eastern Canada are allowed to import oil from countries like the United States, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia without facing a comparable cost or regulatory burden. In 2023, Eastern Canada imported an average of 490,000 barrels of crude oil per day. Decarbonizing only Western Canadian oil would place Western producers at a material, if not ruinous, financial and regulatory disadvantage in global markets.

By thereby cementing two different oil market realities in Canada, the Carney government’s decarbonization policies would render his vaunted One Canadian Economy Act effectively moot, with a situation that denies Western Canada the chance to generate economic value while still achieving little reduction in global emissions. Canadians need to consider carefully whether the concept of “decarbonized” Western Canadian oil represents a “grand bargain” or yet another example of the “running in place” Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen described in Through the Looking Glass.

A cynic might regard requirements for decarbonized Western Canadian-produced oil to be a mere sophistry whereby the Carney government professes conditional support for another oil pipeline while imposing terms that are impossible to meet. And might wonder whether Danielle Smith is unwittingly leading Alberta taxpayers into a financial trap.

Decarbonization is neither economically viable nor just. One might well ask whether it is even logically coherent to speak of “decarbonizing” a substance whose very utility is based on the fuel value of the carbon in it – something akin to “dehydrating” water. And when, in any case, the consequences of ultimately using that substance will be borne by the consuming country. It’s not even as if regular old “carbonized Canadian oil” is so profitable in the first place; investors can do better across the border in North Dakota’s Bakken play, while low-cost Saudi Arabian oil remains profitable at benchmark prices below Canada’s cost of production.

Thus, decarbonization risks placing impossible conditions on Western oil production while ignoring other sources of carbon emissions from imports into Eastern Canada. Canadian regulations for emissions caps and decarbonized oil will not noticeably reduce the growth of global GHG emissions. Other oil producers will simply meet the demands of the international marketplace that would otherwise have been supplied by Canada. And to cap it all, after the tens if not hundreds of billions in lost capital investment suffered under the previous Trudeau government, these policies undermine the appearance of fair practices within Confederation and indeed, may generate irreconcilable differences among its members.

Taking it all together, a cynic might regard requirements for decarbonized Western Canadian-produced oil to be a mere sophistry whereby the Carney government professes conditional support for another oil pipeline, or perhaps even expanded liquefied natural gas production, while imposing terms that are impossible to meet. And, not to put too fine a point on it, might wonder whether Danielle Smith is unwittingly leading Alberta taxpayers into a financial trap.

Ron Wallace is a former Member of the National Energy Board.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.