In the grand chambers and marble-covered halls of the Supreme Court of Canada a political drama is quietly unfolding. The federal government has launched a powerful attack on the provinces, particularly Quebec. By intervening in a Quebec case, Ottawa has invited the Supreme Court to engage in a judicial power grab, initiating what amounts to a game of “Charter chicken” with the provinces. If the Supreme Court accepts the invitation it will further politicize the court, reduce its credibility and upset the balance of Canada’s federal democracy. Last week, the premiers of five provinces asked Prime Minister Mark Carney personally to stop the attack, but his Justice Minister and Attorney General, Sean Fraser, immediately refused their request.

The case before the Supreme Court is Quebec’s 2019 law (Bill 21) barring certain public servants from wearing overt religious symbols such as crosses, hijabs and turbans at work. Anticipating a constitutional challenge, Quebec invoked Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the so-called “notwithstanding clause”, used to shield legislation and some policies by any province, territory or the federal government from judicial review based on the Charter rights in s. 2 or s. 7 through 15. Invoking the clause allows a government to avoid Charter challenges for up to five years. If a government believes it still needs to, it can renew the clause repeatedly. In theory, enough renewals would effectively nullify the Charter right in question within that area of law, in that jurisdiction.

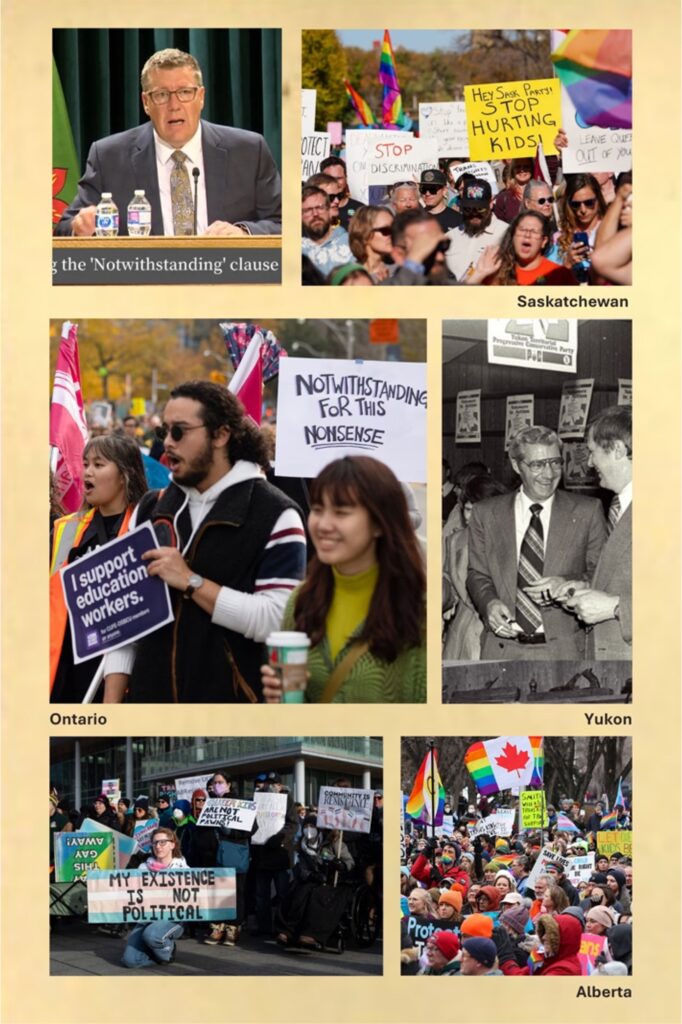

In practice, the use of the notwithstanding clause has been exceedingly rare. In the 43 years since the Charter came into force, Quebec has used it four times, Saskatchewan and Ontario three times each, Alberta and Yukon once each. The federal government has never used it. One of Quebec’s four uses was in 1982, immediately after the Charter was enacted, for an omnibus declaration covering numerous statutes. But it was not renewed. The Province of Quebec was always opposed to the Charter and never signed onto it. Since 1985, Quebec has used s. 33 only three additional times.

Renewals of the notwithstanding clause to protect provincial legislation that may violate the Charter have been rarer still. As stated, Quebec’s omnibus use was not renewed. Nor was its highly contentious 1988 case requiring all public signs to be in French only. When its s. 33 declaration expired, Quebec did not renew it. Five years is a lifetime in politics. Governments fall, priorities shift and compromise often emerges.

Quebec’s two recent uses of the clause in Bill 21, covering the religious symbols in issue in this case, had to be renewed last year because the litigation against it had already been going on for over five years. The Supreme Court recently agreed to hear arguments and rule on the constitutionality of Bill 21. Although it cannot overturn the law itself, some of the dozens of intervenors are urging the Court to prohibit any pre-emptive use of the notwithstanding clause.

On September 17, the Attorney General of Canada filed a memorandum of fact and law or “factum” with the Supreme Court that appears to aim primarily at the recurring use of s. 33. “The prolonged impossibility of exercising a right or freedom would, in practice, be tantamount to denying its very existence,” the factum asserts (page 12). Fraser also weighed in publicly, stating in a news release that, “This case is about more than the immediate issues before the Court. The Supreme Court’s decision will shape how both federal and provincial governments may use the notwithstanding clause for years to come.”

The factum claims to take no position on Quebec’s religious symbols law. But this disclaimer is a political fig leaf. Beneath it lies a strategy to stigmatize and constrain any use of the notwithstanding clause by anyone. The factum says it’s simply trying to help the Supreme Court delineate the constitutional limits of s. 33 in order to protect Charter rights. This implies that the section is vague, that its true meaning awaits judicial revelation and that Ottawa’s advice is necessary to help the court.

But the wording of s. 33 itself is brief, simple and clear: any legislature “can expressly declare” that a law or portion of a law “shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.” The only specified limit is the five-year sunset. The federal factum really invites the Court to amend the Charter through a novel and unjustified interpretation.

The Harm Caused by Excessive Charter Litigation

Also left unstated by Fraser is that some two-thirds of Charter applications fail, and for good reason: they have no valid legal basis. But success in upholding Charter rights is not the primary purpose of many such cases. Charter claims are often used to advance ideological goals through a form of legal harassment that has come to be termed “lawfare”. Lawfare’s purpose is political, using rights litigation to make a political statement or gain publicity.

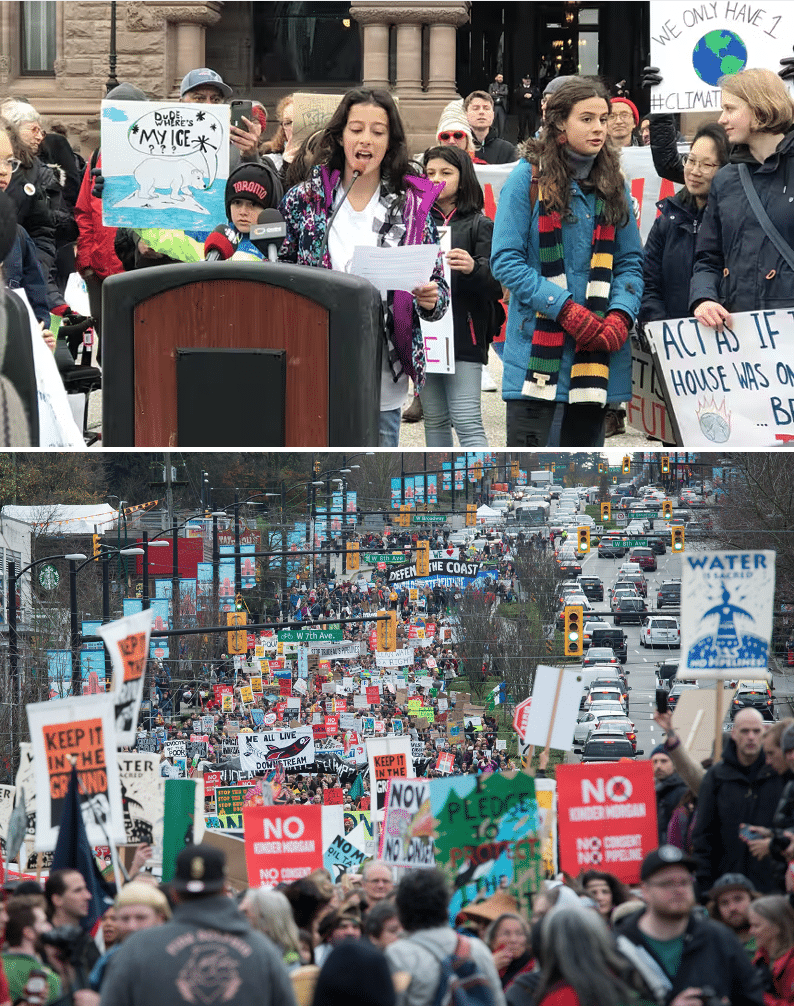

Lawfare isn’t primarily about winning cases. It can be about making laws uncertain for years, or stalling commercial projects until investors run out of money or risk tolerance, as happened with the TransMountain Pipeline expansion. While the process becomes a form of punishment for the litigation’s targets, it becomes a victory for the plaintiffs. Whatever the final court decision, creating years of delay and uncertainty while getting lots of media coverage is victory.

Any Canadian judge can nullify a law for unjustifiably infringing Charter rights, which could not have been done before 1982. Effectively, the Charter created a conditional judicial veto. The veto is conditional because s. 33 allows a province to declare the notwithstanding clause into force, to override (or pre-empt) a judge from using the Charter to strike down a law or policy.

For example, the children’s litigation alleging that the Government of Ontario’s modification of its greenhouse gas reduction targets violates their Charter rights, which I wrote about recently, started almost six years ago. It will probably take three to five more years before final resolution. So the validity of the law they’re challenging remains in limbo for around a decade. S. 33 was included in the Charter to give Canada’s legislatures effective protection against the ravages of Charter-based lawfare.

Who Gets the Last Word in Charter Cases?

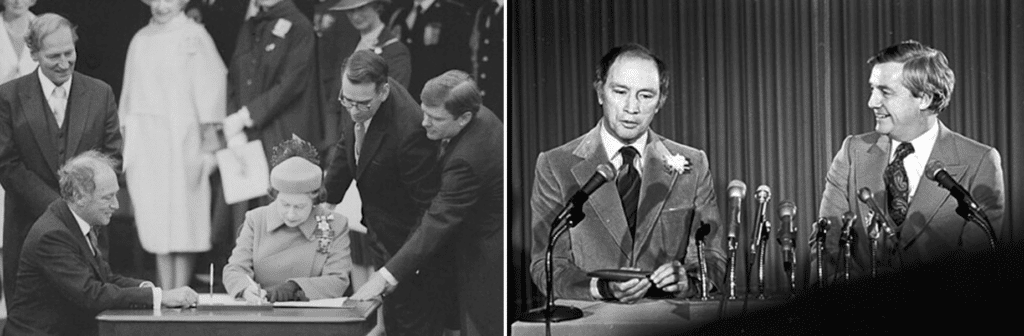

To be fair, Ottawa isn’t entirely wrong in its current argument that the powers given to Parliament and the provinces to enact laws have always been constrained by the Constitution. But which Constitution? Canada’s original Constitution was the British North America Act of 1867, applied through a large, unwritten body of habits and practices (based mostly on British constitutionalism) called “conventions”. Our written Constitution was greatly expanded in 1982 when the Charter came into being after lengthy negotiations between Ottawa and all the provinces, as well as a reference to the Supreme Court.

Since then, any Canadian judge can nullify a law for unjustifiably infringing Charter rights, which could not have been done before 1982. Effectively, the Charter created a conditional judicial veto. The veto is conditional because s. 33 allows a province to declare the notwithstanding clause to override (or pre-empt) a judge from using the Charter to strike down a law. That is the essential Charter balance. Someone must always have the last word; s. 33 gives that to governments, not to the courts. Ottawa is now trying to reverse that through its intervention at the Supreme Court.

I agree with Ottawa that there is a philosophical tension here: legislative supremacy versus constitutional constraint. But there is also a more important real-world tension between the provincial governments and the courts. Everyone makes mistakes, judges as well as elected politicians. But there is a big difference. When politicians get it wrong, they can amend their legislation, not apply it, or allow it to lapse; or voters can throw them out. When the Supreme Court gets it wrong, its mistake remains as a bad precedent, binding the legislatures and lower courts, sometimes for decades. There is no democratic mechanism to correct judicial errors, and there are no consequences for the judges who made them.

What is the notwithstanding clause and why was it included in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, known as the notwithstanding clause, allows a provincial, territorial or federal legislature to pass a law that operates “notwithstanding” individual rights specified in certain sections of the Charter. A law protected by the clause is shielded from Charter challenges under those sections for up to five years; the notwithstanding declaration can, theoretically, be renewed repeatedly for five-year periods, but this has not been the practice.

The notwithstanding clause was included in Canada’s 1982 constitutional compromise to ensure that elected politicians, not appointed judges, would have the final word on certain challenging legal issues. It was intended to serve as a democratic check on judicial power; without the political compromise s. 33 represented, Canada would likely not have amended its Constitution to include the Charter.

Ottawa Invites the Court to Rewrite Section 33

The power of lawmakers is limited by the Charter as applied by judges; the power of judges is effectively unlimited without s. 33. Its very existence is a deterrent to judicial overreach. If the Supreme Court now adds new limits to s. 33 that will create a new imbalance between the lawmakers and the judiciary.

Yes, repeated use of s. 33 could, in future, erode rights. But use of the section is likely to remain rare, and sometimes it is indeed needed when courts discover rights that didn’t exist until last week, creating unintended social and economic consequences. Recall there have been only 12 uses of the notwithstanding clause in nearly 43 years – fewer than one use per legislature in Canada. The courts, by contrast, have issued hundreds of rulings declaring laws or portions of laws constitutionally invalid, requiring that they be amended or stricken entirely.

At its core, the current clash between Ottawa and the provinces is about political philosophy. John Rawls, the distinguished Harvard philosopher, explained that even reasonable people often disagree deeply about the right answer to difficult moral and political questions. The facts are complex, moral concepts are vague, and people weigh competing values differently. Even well-intentioned governments and courts can reach opposite but reasonable conclusions about constitutional issues. Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed, one of the drafters of the Charter, stated the issue in remarkably similar terms.

The Charter’s vague language on rights, especially the s. 7 rights to “life, liberty and security of the person,” is a constitutional Rorschach test, the interpretation of which is in the eye of the beholder. For example, “liberty” to do how much of what, affecting who else, in which way? “Security” against what: unreasonable police searches, or financial security through social assistance payments of a certain standard set by the court?

This open-ended language gives any judge the authority to discover and shape new constitutional rights and, cumulatively, to redefine our moral and social policy. Yet our democratic processes provide no realistic path for correcting judicial rulings on the morality of a law. That is central to why the Charter’s drafters, who were politicians, insisted that s. 33 be included.

The Government of Canada’s current intervention is a rejection of this 1982 compromise, without which there would have been no Charter. The factum wants the Supreme Court justices to rule that they have the last word, even when s. 33 says the opposite. In effect, that is asking the Supreme Court to declare the Constitution itself to be unconstitutional – until the Supreme Court alone amends it.

The federal government apparently believes that the provincial legislatures have been using the section too often, for dubious reasons. The provinces apparently believe that the judges have been striking down laws too often, for dubious reasons. And the Charter’s vagueness encourages frequent rights-focused litigation, which leaves the challenged law in judicial limbo as the case slowly climbs the judicial ladder. Quebec’s secularism or laïcité law in the current case is now six years old, yet the Supreme Court hearings on its constitutionality haven’t even begun.

The federal factum argues that judges should now be able to review laws declared protected by s. 33, and issue a declaration that – notwithstanding the use of the notwithstanding clause – the law unjustifiably infringes Charter rights.

Ottawa’s argument that the judges should give themselves more power over Charter issues is shrewd. The judges, after all, have every incentive to give themselves more power. Self-restraint is a rare virtue. It will take a lot of this virtue for the court to reject Ottawa’s invitation.

The factum and Fraser in his public statements, meanwhile, are couching everything in the language of rights for “Canadians”, presenting themselves as altruistic, motivated only by concern for the Constitution and the welfare of Canadian citizens. But Canadian citizens vote for their provincial governments, too, and a provincial government is far closer to and more representative of the will of its voters than Ottawa. Yet here Ottawa is attempting to sharply curtail the constitutional status and legislative freedom of every province and territory.

What is the constitutional conflict surrounding Quebec’s 2019 law, Bill 21?

The conflict involves both the substance of Bill 21 and Quebec’s use of Section 33, the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, to protect it from judicial review. Passed in 2019, Bill 21 bars certain public servants from wearing overt religious symbols, such as crosses, hijabs and turbans, while at work.

By invoking the notwithstanding clause, Quebec shielded the law from challenges based on rights specified in certain sections of the Charter. A number of groups immediately asked the Supreme Court of Canada to rule on the matter, which it agreed to do only in 2025. In September 2025, the Government of Canada intervened in the case, asking the Supreme Court to establish new limits on the application of the notwithstanding clause. This action created a direct clash between Ottawa and at least half of Canada’s provinces, including Ontario and Quebec. The matter was ongoing in late 2025.

Turning the Supreme Court of Canada into a Political Actor

The factum argues that judges should now be able to review laws declared protected by s. 33, and issue a judicial declaration that – notwithstanding the use of the notwithstanding clause – the law infringes Charter rights. Such a declaration could not strike down the law; it would simply be a moral opinion that the law unjustifiably infringes the Charter.

Although the legal effect of this would be nil, its political effect would be substantial. The media would headline that the province is trying to protect an unconstitutional law. The opposition parties, interested academics and the organizations that litigated the case would gain a new political weapon provided by the court. This would shape public perception and might influence voters in future elections. Knowing that this is what they can expect might well have a deterrent effect on legislatures, further constraining the already rare use of s. 33.

The Government of Canada’s intervention is thus encouraging the Supreme Court to become more of a political actor. Politicizing the judicial branch of the Canadian state in this way would be more damaging to the public respect and credibility of the judges than it would be to any province a court would be criticizing.

Why the Government May Win

The federal government is well-aware that judges have historically disliked any provisions that circumscribe or supersede the jurisdiction of the courts. Now it has provided the Supreme Court’s judges with some suggested new ways to overcome such limits built into the Charter.

Historically, so-called “privative” clauses have sometimes been inserted into statutes to try to keep judges from over-ruling administrative decisions. In a prominent New Brunswick case concerning employment law, the Supreme Court in 2008 held that while a privative clause signals legislative intent to minimize judicial interference, such a clause is not determinative. In other words, courts ultimately decide the limits of their own authority.

But s. 33 is different. It’s not just a clause in a statute; it’s part of the Constitution itself. The Supreme Court can’t declare it invalid. But it could decide to impose Ottawa’s suggested limitations on its use. That would be a breathtaking act of judicial power and would severely upset Canada’s constitutional balance between the legislative and judicial branches.

Some journalists have recognized that the government’s factum is an attempt to get the Supreme Court to amend Canada’s Constitution through the back door. As the Globe and Mail put it in a recent editorial, “One need not enthuse over the notwithstanding clause to see the danger in Ottawa looking to contort the plain meaning of the words in the Constitution in order to avoid the messy work of securing an amendment by winning over the country to its view.” (For the record, amending Canada’s Constitution requires gaining the assent of the federal government plus the legislatures of at least seven provinces representing at least 50 percent of the country’s population. The Supreme Court, interestingly, has no role in this process.)

How does the Government of Canada’s legal intervention in the constitutional challenge to Quebec Bill 21 propose to change the use of the notwithstanding clause?

The Attorney General of Canada’s September 17, 2025 factum intervening in the Quebec Bill 21 case asks the Supreme Court of Canada to impose new limits on provincial legislatures’ use of Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The factum argues that a province’s repeated use of the notwithstanding clause is equivalent to denying the existence of a Charter right and thus constitutes an unauthorized amendment to the Constitution. The factum’s reasoning invites the court to amend the Charter – part of Canada’s constitution – through a new judicial interpretation rather than through the constitutional amendment process, which involves elected legislatures and not the courts.

The government also proposes that judges should be able to issue a declaration stating that a law protected by the clause infringes Charter rights. Although this could not legally strike down the law, it would serve as a powerful political weapon. It would shape public perception and could have a deterrent effect on legislatures, constraining the already rare use of s. 33, which from 1982 through 2025 had only been invoked a total of 12 times across Canada.

Who Should Make the Law?

Beneath all the legal argument lies an age-old question: who should make the law, the people’s elected representatives or the judges appointed to protect the Constitution? In theory, elected governments derive their legitimacy from the voters. But in truth, as Andrew Coyne explains in his new book The Crisis of Canadian Democracy, most MPs and even cabinet members have no real legislative authority. Real decision-making is concentrated in the Prime Minister’s Office, run by unelected staff. The situation is similar in the provincial premiers’ offices.

In addition, Parliament is far from perfectly representative of the people’s will. For example, in the 2021 federal election the Liberal Party under Justin Trudeau won just 32.6 percent of the popular vote but gained 47.3 percent of seats in the House of Commons, enough to continue as a minority government. The Conservative Party won 33.7 percent of the popular vote, more votes than the Liberals, but gained only 35.2 percent of the seats. Altogether, 67.4 percent of voters did not vote for the party that continued to govern the country. As well, the federal riding with the largest population has six times more people than the one with the smallest population, so the principle “representation by population” is not fully achieved. These realities weaken the moral case for legislative supremacy.

On the other hand, Supreme Court justices are effectively appointed by the Prime Minister. The current government has appointed six of the nine Supreme Court justices and elevated a seventh to Chief Justice. While judges owe no loyalty to the party that appointed them, governments rarely pick candidates whose views are inconsistent with their own values. This weakens the case for judicial supremacy.

Don’t Fix What Ain’t Broke

The federal government claims to be concerned that excessive use of s. 33, especially the renewal of the notwithstanding clause to keep certain laws in force, renders some Charter rights unavailable. Such “irreparable impairment of a right or freedom,” the government’s factum states, “would constitute an unauthorized amendment of the Constitution.”

Which Charter rights have been irreparably impaired? The actual evidence of such damage over 43 years is unpersuasive; some would call it entirely absent. And if such a trend was to emerge in future, it would probably be in response to excessive judicial creativity in expanding Charter rights to strike down legislation or government policies. That would create further distrust of the courts and encourage more use of s. 33.

‘Put simply, the federal government’s arguments represent a complete disavowal of the constitutional bargain that brought the Charter into being,’ the letter from five premiers to the prime minister states. ‘These arguments threaten national unity by seeking to undermine the sovereignty of provincial legislatures.’

There is no perfect constitution, no infallible decision-maker, whether politician or judge. Every democratic system has its flaws, its blind spots and its “pick-your-poison” trade-offs. In the end, the real issue isn’t just about religious symbols or even about s. 33. It’s about what kind of democracy Canadians want and who gets to define it. The Supreme Court may decide that despite the clear wording of s. 33 it will have the last word. But if so, the debate won’t end there.

That’s because although the Charter embodies lofty ideals it describes them in language so ambiguous that it is meaningless without interpretation both by politicians and judges. The Charter’s effectiveness and legitimacy depend on mutual respect and restraint between governments and the courts. Federal Justice Minister Fraser’s posture of rights protection in the Quebec Bill 21 case, if adopted by the Court, would be destructive of the Charter’s balance achieved over the past 43 years.

It is no exaggeration to describe Ottawa’s factum as trying to create a constitutional crisis; just last week the premiers of Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia issued an open letter addressed to Carney calling upon him to withdraw the factum. “Put simply, the federal government’s arguments represent a complete disavowal of the constitutional bargain that brought the Charter into being,” the letter states. “These arguments threaten national unity by seeking to undermine the sovereignty of provincial legislatures.”

With Fraser immediately and almost scornfully rebuffing the letter, we can only hope that the Supreme Court will decide to keep on being just an apolitical court by declining the current government’s urging to become robed politicians ruling us from their marble halls.

Andrew Roman is a retired litigation lawyer with extensive experience in environmental, administrative and constitutional law.

Source of main image: AI.