Modern Canada is a dynamic, constantly expanding society, continually creating new wealth, continually increasing its spending on the goods and services Canadians want and need. It is not a lifeboat, whose first mate, pistol at the ready, grimly doles out the ration of hard tack and fresh water. A country that as a matter of public policy bars treatment to the sick in the hour of their need and pain has lost its moorings and drifted into the unnecessary acceptance of a bizarre form of social cruelty.

— Michael Bliss, 1941-2017, Canadian historian and author

The B.C. government recently ordered its ostensibly independent Medical Services Commission to audit Telus Health MyCare to determine whether Telus was engaged in providing “two-tiered” health care by offering virtual and in-person medical consultations through its recently opened care centres.

The commission’s stated mandate is facilitating “reasonable access to quality medical and diagnostic facility services for residents of British Columbia.” That is what Telus says it is attempting to do through its health services, which began operating in 2019. It seems the government’s main objection is that the clinics’ presence is focusing attention on the deficiencies in our public health care system and highlighting the government’s (and commission’s) failure to fulfil their promises to suffering patients. One of the Telus clinics, operating under the name Copeman Healthcare, was audited about 15 years ago (when it was still independent), and that audit found no violations. The new audit appears aimed at distracting the public and media from core issues that have been the subject of daily news reports.

Virtually no-one disputes that Canadians have insufficient access to high-quality health care on a timely basis. One of the main reasons for this is that there are simply not enough doctors and nurses to get the job done. About 30 years ago, Canadian governments – led by B.C. – created the current medical manpower crisis by closing many nursing schools and cutting enrolment in medical schools. They did so on the advice of another government-controlled commission, the 1991 B.C. Royal Commission on Health Care and Costs, headed by Justice Peter Seaton. The commission was tasked with probing the rising cost of health care in the province. It concluded that this was occurring partly due to an overabundance of doctors, and many of its recommendations to governments aimed to reduce the future supply.

Too many doctors were, allegedly, providing too much health care. The objective of restricting the supply of doctors, then, was not to increase the efficiency of how health care was delivered, but to reduce the amount of health care provided.

Commission member Robert Evans had previously written: “A central cause of the [cost] problem was the oversupply of physicians, which tended to generate greater utilization of services…a [hospital] bed built was a bed filled.” The commission’s report and recommendations reflected this supply-reducing mindset. Among its other recommendations were, “State clearly that immigrant physicians do not have a right to practice medicine in B.C.,” and, “Require visa trainees to agree not to stay in Canada when they complete their training.” It is important to understand the reasoning here: too many doctors were, allegedly, providing too much health care. The objective of restricting the supply of doctors, then, was not to increase the efficiency of how health care was delivered, but to reduce the amount of health care provided.

One must admit, it certainly worked.

Governments worsened the gathering crisis by increasingly rationing Canadians’ access to medical services, underpaying health care workers, and creating very poor working conditions. A once excellent health-care system is in crisis and governments are primarily to blame.

According to the IndexMundi statistical data portal, Canada now ranks 69th in the world in the number of doctors per capita. Back in the 1970s, our world ranking varied between fourth and eighth. Our current nursing shortage, however, is not just in absolute numbers. We actually exceed the OECD average in nurses relative to population. More significantly, burnout among practising nurses is a long-standing problem. The workplace in many institutions has become toxic. In 2013, well before the Covid-19 crisis, the CBC reported that nearly 25 per cent of Canadian nurses wouldn’t recommend their hospital and 40 per cent were plagued by burnout.

One shortage that does not afflict Canada’s system is the supply of health care bureaucrats. As this Calgary Herald article (part 1 of a series) notes, “Canada has one healthcare administrator for every 1,415 citizens. Germany: one healthcare administrator for every 15,545.” And Germany’s system, the article adds, is consistently rated better than Canada’s, with more physicians, more nurses, more hospital beds and more diagnostic equipment per capita. The only things Canada has more of are waiting times and “paper-pushers.” We have 14 ministries of health, while France with double the population has one. In this-self propagating system, each minister has deputies, associate deputies and assistant deputies.

Among the biggest problems afflicting Canada’s health care system is not the amount of money we spend but how the funds are allocated. Canadian hospitals typically receive a fixed annual budget. This creates an unhealthy relationship between hospital and patient, because it causes hospitals to perceive patients as undesirable “cost items” who steadily consume the annual funding allocation. Eventually, all those patients use up all the funding and the hospital risks going into deficit.

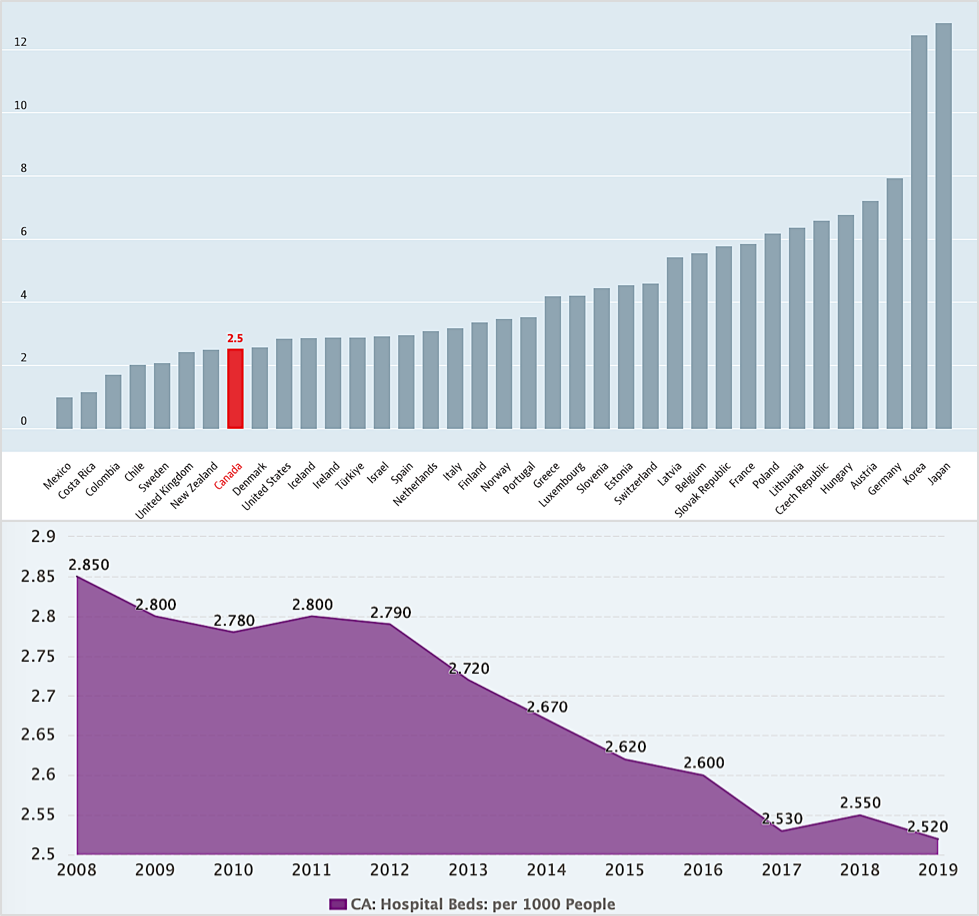

The simplest way to deal with that is to limit the amount of health care the hospital provides, i.e., to delay procedures or refuse admissions. That phenomenon helps to explain those media accounts of brand-new hospitals with entire empty storeys. It also helps explain why Canada has so few ICU beds relative to population, because those beds are especially expensive to equip and operate.

One characteristic of many better-performing OECD countries is that hospitals receive their funds on a per-patient procedure or visit basis. Funding “follows the patient”: the more procedures hospitals perform and the more patients they serve, the more money flows their way. Hospitals then desire and even compete for patients. (In Switzerland, some hospitals actually do billboard advertising along busy freeways.) The opposite happens here in Canada.

The absurdity of having new, fully equipped buildings with hundreds of administrative and support staff, but without nurses, doctors or patients, was the subject of a classic episode in the British comedy series ‘Yes, Minister.’ Making that satirical scene a recurring reality is not funny.

The Covid-19 pandemic could have provided a rare opportunity to revisit the deficiencies in Canada’s health care system and initiate badly needed reforms. Instead, it activated the Canadian instinct to see just about any proposed reforms or innovations in health care as an undercover campaign for “American-style” health care.

Fixed budgets have also decreased the funding available for nurses and doctors, to a level where the visit fee for a family doctor in B.C. is just over $30. The doctor must pay all of their office and staff expenses from their hourly revenue. That has forced many to close their offices. House calls by a general practitioner pay about one-third of the amount that an appliance repair technician receives.

Of course, there are some Canadians who don’t suffer the predictable effects of our dysfunctional system. Politicians endorse their own privileges and enjoy such benefits as tax-funded private insurance for medicines, dentistry, physiotherapy and ambulance services. They could demonstrate their sincerity if they voluntarily declined such two-tier benefits. Most low-income citizens do not enjoy such privileges. Telus Health’s fees, for example, apparently cover annual medical examinations, preventive measures and fitness assessments, none of which is covered by the B.C. government’s medical plan. The simple solution to eliminating those additional fees, and providing access to all, is for government to cover preventive and screening examinations.

Something urgently needs to be done. Millions of patients are suffering and more than 11,000 are dying every year as they wait for health care in Canada. Entrenched ideologies have rationed access and fought all competition. Governments do not carry out performance checks and, thereby, avoid accountability. Instead of attacking independent providers, governments should match their service levels. Telus Health is embarrassing government by exposing its deficiencies.

Like other provinces, however, B.C.’s government is hiding from reality by spending vast public funds on infrastructure and new buildings. Politicians can then attend gala openings as they place self-congratulatory plaques. The absurdity of having new, fully equipped buildings with hundreds of administrative and support staff, but without nurses, doctors or patients, was the subject of a classic episode in the British comedy series Yes, Minister. Making that satirical scene a recurring reality is not funny.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that Canada spent 13.7 per cent of its GDP on health care in 2020. The total amounted to $308 billion by 2021 ($8,019 per Canadian). No other universal health care system in the world reports spending that much. Yet the 2021 Commonwealth Fund ranks Canada near the bottom in access to care, last in caring for low-income groups and last in equity when compared with other developed countries that offer universal care.

Canadian governments have somehow come to believe that if they cannot deliver timely care, no one else should be allowed to do so, and that competition is undesirable because better-performing alternatives expose and highlight the inefficiencies in our state monopoly. Far from actually tackling any of the system’s problems, and worse even than just standing idly by, Canadian governments are actively working to prevent anyone from pursuing innovations that would provide Canadians with better, quicker health care. That is a clear attack on every citizen’s personal autonomy and bodily integrity. As Michael Bliss wrote, this represents an offensive and bizarre form of social cruelty.

Brian Day is an orthopedic surgeon, health researcher and Medical Director at Cambie Surgery Centre, a private hospital in Vancouver, and was president of the Canadian Medical Association in 2007-2008.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.