As the former Auditor-General for Newfoundland and Labrador, Senator Elizabeth Marshall has an eye for financial detail. More importantly, she can spot its absence. At a Senate hearing in early December, Marshall grilled Liberal Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland on her plan, already approved by the House of Commons, to deposit an initial $2 billion in the Canada Growth Fund, a key component of the Justin Trudeau government’s new industrial policy. Marshall’s problem: the Canada Growth Fund doesn’t actually exist.

“There is no legislation that tells us anything about this yet-to-be-created corporation,” Marshall lectured Freeland. “We don’t know anything about the composition of the board [of directors], or even if there will be a board. There is nothing to tell us about the financial controls to be exercised over the $2 billion. And nothing to indicate what the governance structure will be.”

Freeland’s response? “We need to move really, really fast,” she told Marshall, citing U.S. President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which is already handing out US$369 billion in subsidies to American businesses. “Getting this fund in place quickly is more important than ever…given the hundreds of billions of dollars that the U.S. is deploying.” And so, fiddly little details such as creating a proper mandate or governance structure to oversee the disbursement of billions in taxpayers’ money must take a backseat to the urgent need to get the fund up and running. “Canada has to move faster than we have hitherto,” Freeland added.

Welcome to Canada’s new industrial policy – handing out money faster than ever. Who’s feeling lucky?

Canada’s New Industrial Policy

The Canada Growth Fund (CGF) and another yet-to-be-created organization called the Canadian Innovation and Investment Agency (CIIA) lie at the centre of the federal government’s new fixation with industrial policy. Once properly constituted, the CGF is supposed to provide $15 billion in subsidies, equity investments and other support payments to encourage companies to participate in “the green transition” – not only meddling in the market place but also inserting Ottawa’s climate change agenda even deeper into the Canadian economy.

These days everyone from wonkish think-tanks to mainstream business groups are demanding Ottawa adopt a ‘bold industrial strategy.’

The CIIA is meant to boost private-sector spending on research and development by allocating public funds in a similar fashion, but without the carbon-free requirement. (It may instead choose to distribute its money to “businesses with an equity/diversity focus,” as a consultation report advises; this presumably means firms controlled by members of designated minorities.) In her Fall Economic Update, Freeland presented both new organizations as the government’s response to Canada’s need for “a real, robust industrial policy.”

The CGF and CIIA have been seen as evidence the federal government is returning to a more activist role in charting the overall course of the economy and influencing how firms allocate their resources, particularly with respect to R&D. It is a plan with plenty of supporters these days, as everyone from wonkish think-tanks to mainstream business groups are demanding Ottawa adopt a “bold industrial strategy.” Of course, industrial strategy – also known as politicians handing out cheques and other goodies in the name of jobs and economic growth – has never really gone out of style. Canada’s bounty of regional development agencies, global innovation clusters, grant programs and a host of other policies at the federal and provincial level all testify to that.

Yet the two new funds mark a clear shift in emphasis to make “picking winners” the dominant focus. Currently, the main component of federal innovation policy is the longstanding Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) program, which offers $3.6 billion in annual refundable and non-refundable federal tax credits (plus ancillary provincial tax credits) to firms doing research with a commercial focus.

While SR&ED has been criticized for favouring smaller firms while larger firms produce a proportionately greater share of R&D, it is broadly distributed and based on established criteria outside the influence of bureaucrats and politicians. Now the Trudeau government says it’s reviewing SR&ED and shifting its attention to more direct government influence over the economy and its future direction. This means more ad hoc decisions about which specific firms in which favoured sectors will benefit from public largesse. And in ways that put taxpayers at much greater risk.

Among the CGF’s tools will be the authority to take on “contracts for difference.” This means it will guarantee a certain price for various products or commodities, such as hydrogen, in order to ensure a particular project is profitable for a particular firm. It can also arrange “offtake contracts” in which it agrees to purchase all of a firm’s production if it can’t find any actual buyers. All this is meant to “incentivize companies to take risks.” In truth, the financial risks will be transferred to the government and taxpayers will assume all the financial burden when things go wrong.

‘This notion that we need to trust political and bureaucratic expertise in business has always struck me as odd,’ says Boudreaux. ‘These are people who have no demonstrated expertise at discovering profit opportunities.’

As for the CIIA, its job will be to spot innovative R&D opportunities at an early stage and provide them with public funds to reach commercial success. It’s to be based on similar models in other countries, and in particular the Israel Innovation Authority. Of course, to consistently pick winners in this fashion, both organizations will require highly-skilled staff poached from the private sector. “We understand that we need to have actual investment professionals do this work,” Freeland said at the Senate hearing last month.

As Freeland made clear to Marshall, her urgency in rolling out the CGF comes from the Biden Administration’s revival of activist industrial policy. The absurdly-named Inflation Reduction Act not only promises the aforementioned US$369 billion in direct business subsidies meant to stimulate green energy and other climate-related projects, but an additional US$350 billion in federal loan guarantees destined for similar purposes. Such a tidal wave of government money sloshing around the U.S. is already having a huge impact on business and political decisions around the world.

Remembrance of Failures Past

“Industrial policy is certainly enjoying a resurgence,” observes Don Boudreaux, an economist at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia and a senior fellow with the Fraser Institute in Vancouver, B.C. Boudreaux, who has written extensively on industrial policy, sees the current enthusiasm as an echo of the 1970s and early 1980s, when political interest in regulation and government intervention in the economy was equally high. “The left has always supported it, but now we’re seeing the impetus coming from the right as well,” he notes in an interview, pointing to the influence of right-leaning, industrial policy-supporting organizations such as American Compass in the U.S. and Canada.

Boudreaux suggests this revival may be due to a form of collective amnesia. “People seem to have forgotten the disastrous record of these policies in the first place, and the overall failure of central planning,” he says. With the free markets/free trade era that began in the late 1980s now coming to an end, he sees it being replaced by a renewed faith that governments can outthink and outperform markets. But “it’s going to fail,” he predicts. That is because it ignores the reasons why markets work in the first place.

“This notion that we need to trust political and bureaucratic expertise in business has always struck me as odd,” says Boudreaux. “These are people who have no demonstrated expertise at discovering profit opportunities.” Besides, he observes, no one – not even market experts – knows for certain which industries or ideas will prove profitable. The recent collapse of highly-touted cryptocurrency firm FTX and the arrest of founder Sam Bankman-Fried underlines how often “actual investment professionals” (as Freeland puts it) can be made to look foolish by the vagaries of the stock market. But when governments seek to invest in the “industries of the future” it is not their own money they’re risking – it is taxpayers’.

While governments picking winners may be back in fashion, experience demonstrates that the far more likely result is taxpayers backing losers. Boudreaux points to the collapse of sustainable energy firm Solyndra as an example of recent American industrial policy failure. Solyndra produced unusual cylindrical solar panels that were touted as being extremely efficient, capturing the imagination of green investors and credulous politicians. The firm burned through US$535 million in loans guaranteed by the Obama Administration – and then filed for bankruptcy in 2011.

Going a bit farther back in time, the UK prior to the Thatcher Revolution was burdened by a rigid government/union-led industrial strategy that focused on propping up key industries such as automobile and aerospace manufacturing. Evidence of this national fiasco includes such famous nameplates as British Leyland, which was partially-nationalized in 1975 and then sold off in stages at an overall loss, and the futuristic but money-losing supersonic Concorde passenger jet. Europe too is replete with failed government efforts aimed at besting the private sector. One example among many: a joint French-German 2008 effort at creating a “Google-killer” search engine called Quaero. It didn’t work.

All of the above were initially presented as innovative, technologically-advanced ideas merely requiring a bit of public assistance to get off the ground. All earned the attention of generous politicians for their claims to represent “industries of the future.” And all came a cropper, either for business reasons or as a direct result of the deadening hand of government involvement.

Canada’s Gift to Airbus

For Canadians, homegrown evidence of industrial strategy’s futility and costliness can be found in the unhappy tale of Bombardier’s C Series jet. From its inception in the early 2000s, the C Series ticked boxes as fast as government bureaucrats could imagine them. Built to take advantage of a gap in the product lines of Airbus and Boeing, the C Series was an innovative Canadian-designed single-aisle jet that promised a huge reduction in fuel consumption and the quietest ride in the industry. Even better, it was pitched by Canadian business icon Laurent Beaudoin, who had transformed Bombardier from a modest Quebec-based snowmobile manufacturer into a global transportation sector behemoth. From 2012 to 2018 the company was Canada’s biggest spender on R&D by a substantial margin, often doubling its nearest competitor.

All this was seen as unmistakable evidence of industrial policy virtue. Yet Bombardier continually struggled to deliver on its deadlines and the C Series project eventually went far over budget. Befitting its role as a national champion, Bombardier repeatedly looked to government for help. In 2008 the Conservative government of Stephen Harper provided $350 million in loans. Then in 2015 Bombardier received a $1.3 billion equity investment from the Quebec government. In 2017 it received another $372 million loan from Ottawa, courtesy of the Trudeau government.

Despite all its politically-motivated assistance, however, Bombardier was never able to break the commercial jetliner duopoly of Boeing and Airbus. Boeing brought an anti-dumping suit against the C Series in the U.S. in 2017 – arguing the firm’s ample government assistance amounted to an unfair subsidy – and Bombardier was eventually forced into a humiliating deal with Airbus simply to keep the project alive.

Bombardier has since relinquished all control over the plane, which is now known as the Airbus A220. And while Quebec retains a 25 percent ownership stake in the project, the current value of the province’s investment is zero. As for Europe-based Airbus, it considers the A220 a great success, largely because Canada handed it all that taxpayer-subsidized R&D at a huge discount. And any ongoing benefit to the Canadian economy seems tenuous. Airbus retains a production line at Mirabel airport north of Montreal, but also has a much larger A220 manufacturing facility in Mobile, Alabama.

The Forgotten Lessons of Largesse

When it comes to industrial strategy, says Franco Terrazzano, federal director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, “Bombardier is the perfect warning signal. After more than a billion dollars spent, the taxpayer investment is now worthless.” In an interview, Terrazzano points out that any industrial policy using subsidies or preferential loans to insulate private firms from business risk ends up “creating a perverse incentive. It shifts the focus of the business from, ‘How can I deliver the best product to meet market demand?’ to, ‘How can I get the biggest subsidies?’” As for Freeland’s rush to roll out her new industrial policy, he quips, “It sure smells like corporate welfare.”

Brassard says the province made serious mistakes in how it structured its deal with Bombardier in 2015, which ultimately led to the investment’s complete loss in value.

Terrazzano notes that last summer his organization gave Quebec’s government a provincial “Teddy Waste Award” for its profligacy in sinking an additional $360 million into the A220 project in 2022 to keep the remaining Mirabel jobs in place for another eight years. In 2016 the taxpayers’ group also gave Bombardier a satirical “lifetime achievement award,” commemorating Bombardier’s first government handout 50 years earlier. According to the Montreal Economic Institute, Bombardier has received $4 billion in public loans and grants since 1966. Rather than picking winners, industrial strategy more often than not involves politicians picking their friends.

“Quebec made a bad deal” with its Bombardier investment, admits David-Alexandre Brassard in an interview. Brassard is chief economist at CPA Canada (which represents Canada’s chartered professional accountants). Prior to his current job, Brassard worked at Quebec’s Ministère de l’Économie, de l’Innovation et de l’Énergie where he was tasked with evaluating “strategic interventions” of $10 million and above. He says the province made serious mistakes in how it structured its deal with Bombardier in 2015, which ultimately led to the investment being written down to nothing. As such, it highlights the many difficulties that arise when governments try to play in the market.

There are plenty of reasons to worry that Ottawa’s new innovation strategy is fated to repeat the errors of the Bombardier experience. For example, Brassard observes how the CGF’s planning process seems fixated on a “top-down” approach to innovation, in which government officials decide for themselves the most promising sectors and industries and then sprinkle their largesse accordingly.

The experience in Israel (on which, recall, Canada’s new innovation agency is to be modelled), Brassard says, is to allow innovation to percolate up from the bottom, without government setting guideposts or restrictions. This at least allows market participants rather than bureaucrats and politicians to influence the direction of innovation policy. Further, Brassard worries the predictable Canadian preoccupation with imposing regional balance and other political considerations on every government program could get in the CGF’s way as well. “Politicians are not good at figuring out what is innovative and what is not,” he observes. “If they were, they’d be investors.”

Can China Pick Winners?

In addition to poor collective memory and an irrepressible desire to meddle in the economy, another reason behind industrial policy’s sudden reappearance is what Boudreaux calls “the China Scare.” Biden’s massively-inflationary Inflation Reduction Act and assorted other recent policies are meant as a deliberate response to China’s perceived dominance in certain crucial industries, such as electric vehicles (EVs), batteries and computer chips.

Many observers feel this gap is the result of the Chinese government directly encouraging and shaping domestic investment in these strategic areas. If China has gained a step on American ingenuity through state control of the economy, the logic goes, then the U.S. must respond in kind. But, as Boudreaux argues, “There is no reason to believe that Chinese mandarins are any better at picking winners or anticipating the industries of the future than Western bureaucrats.”

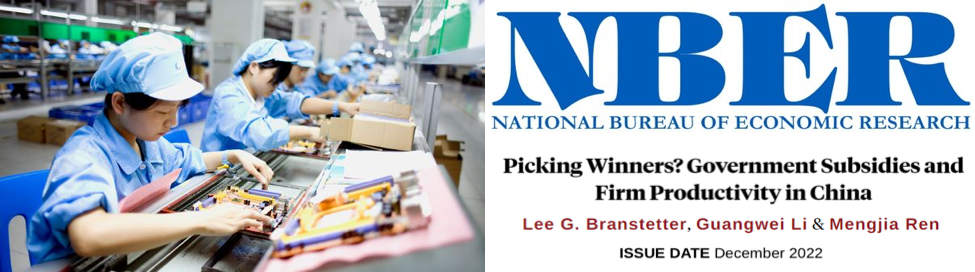

His skepticism is bolstered by a recent paper from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research. The researchers, from Carnegie Mellon and ShanghaiTech universities, report there’s “little evidence that the Chinese government picks winners – if anything the evidence suggests that direct subsidies tend to flow to less productive firms rather than more productive firms.” Between 2007 and 2018, the paper asserts, direct government subsidies in China were “negatively correlated” with productivity. “Even subsidies given out by government in the name of R&D and innovation promotion,” the researchers write, “do not show any statistically significant evidence of positive effects on subsequent firm productivity growth.”

Despite the habitual self-confidence of government officials in their ability to spot promising sectors and businesses, the track record of such activity is abysmal everywhere – from market-based democracies to command-and-control dictatorships. The sudden resurgence of industrial policy in Canada thus results from a doomed daisy chain of faulty reasoning. Freeland claims Canada must spend quickly and aggressively to keep pace with the Americans, who are spending hundreds of billions in an effort to keep up with China, which evidence suggests is not actually outperforming anyone with its own industrial policy.

Even more worrisome, in trying to beat China at its own game, Western economies risk giving up their greatest advantage – the ingenuity and creative destruction inherent to a market-based approach to innovation. As Boudreaux points out, corporate strategies that aim to maximize government largesse are rarely profitable in the long run and tend to attract the wrong skillset. Echoing Terrazzano, he observes: “If you are dependent on government subsidies for your success, then your talents likely lie in public relations and lobbying government for money, rather than searching out private financing or shaving pennies off production costs.” Replacing the relentless search for profit with an equally relentless search for government aid demolishes the foundation for private-sector innovation.

‘To the extent that creating a “green economy” may be a benefit to the environment, it comes at the expense of the economy itself. There is a trade-off that the peddlers of this new industrial policy are ignoring. You can’t have both.’

As for the CGF’s scheme to “incentivize risk-taking,” Boudreaux responds, “What they are really doing is shielding the private sector from actual market risk. When you spend your own money, you spend it more carefully.” And, he points out, when it becomes clear a project is a money-loser, profit-minded entrepreneurs are quick to pull out and move on to the next opportunity. “Politicians have non-monetary reputations to worry about,” Boudreaux notes. “Rather than admit that something is a failure, they are more likely to say the problem is ‘we haven’t spent enough money yet.’” That was certainly the case with Solyndra, British Leyland and Bombardier’s C Series jet – making their eventual failures all the more costly and damaging.

The true scale of loss caused by activist industrial policy is impossible to calculate. Who can tell what potentially ground-breaking private-sector projects or investments might have gone ahead in the absence of the many billions of dollars of distorting government subsidies? The formidable power of this hidden effect is illustrated in Europe-based carmaker Stellantis’ recent decision to shut down a factory in Belvidere, Illinois that produces gasoline-powered Jeep Cherokees. According to the firm, “the increasing cost related to the electrification of the automotive market” pushed it to shutter the 1,350-worker plant (first opened in 1965) so as to throw more corporate resources at EV production. Citing the array of carrots and sticks associated with EVs in the Inflation Reduction Act, the Wall Street Journal noted, “Government industrial policy doesn’t give the company much of a choice.”

If there is one major difference between the current version of industrial policy and those of the past, says Boudreaux, it’s that an entirely new set of objectives and complications has been added. In previous eras, politicians claimed to be using subsidies and other inducements to boost economic growth and create jobs. Now these goals are freighted with the additional and daunting goal of creating a new carbon-free economy – what Freeland calls the “green transition.”

But as Boudreaux asserts, “These two goals are actually constraints on each other. To the extent that creating a ‘green economy’ may be a benefit to the environment, it comes at the expense of the economy itself.” Building a green economy requires tearing down the old carbon-using economy. And that entails enormous costs to the status quo, as those Jeep-plant workers recently discovered. Boudreaux adds, “There is a trade-off that the peddlers of this new industrial policy are ignoring. You can’t have both.”

The sensible alternative to this pattern of uncreative destruction isn’t likely to win much political support these days, he admits. But it’s still worth promoting. “We should give entrepreneurial ability and creativity as wide a scope as possible,” Boudreaux advocates. “That means freeing up markets, encouraging private-sector innovation and allowing people to spend – and lose – their own money by making the investment environment as friendly as possible. Only then, through genuine competition, will we discover what particular industries, sectors or ideas are the ones that will generate the highest returns in the future.”

Sure, sure Freeland might say. But all that takes time. And the credit for success lies elsewhere. For politicians determined to take “urgent” action, nothing satisfies like a quick round of winner-picking. Betting with other people’s money just adds to the thrill.

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior features editor at C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.