There is an obsession infecting our political speech that has become so prevalent it could be called the great narrative of our public life. On the one hand Western leaders, activists, bureaucrats and legacy news media – the entire “elite”, really – revel in hectoring their citizens on the inestimable value of inclusion, acceptance and empathy. At the same time, they spend an inordinate amount of time uncovering and condemning hatred. This dual-sermonizing has come to define much of the past 15 years.

As for what is hateful, the list is endless: patriotism, familial loyalty, religious dedication, merit, virtue, intrinsic beauty, condemnation of criminal malfeasance, intellect, scientific rigour, objectivity, moderation, fairness. All are targets in the great hate turkey-shoot. Even equality, the crown of our modern democratic dispensation, is now deemed heinous and finds itself crushed under a landslide of amorphous “equity”.

Those of us on the receiving end of this campaign have come to see that something is deeply amiss. After more than a decade of woke hectoring, we know in our minds and feel in our guts that this habit of tainting all manner of actions and thoughts with the toxic tincture of hate is itself a form of pathology. We hear the invocation of inclusion but see only the malice of obfuscation.

On top of it, we have come to recognize that most of this comprises duplicitous phrases without any connection to real actions, such phrases as virtue-signalling and sheer chicanery. What phrase is picked appears to depend in part on what Canadian theologian and philosopher Bernard Lonergan called scotosis – meaning intellectual blindness. So when faced with the tangible outcomes of actual hatred – the massacre at Bondi Beach, for instance – our self-appointed schoolmarms revert without missing a beat to their vacuous memes invoking humanity and unity along with their stock phrase: “There’s no room for hate in [insert jurisdiction here].” Having done their oracular duty, these false prophets slink off: words without meaning, speech without consequence.

The obsession with hatred and the flagging as hateful things that common sense and experience have deemed worthwhile suggest it is the accusers whose overriding motivation is hate. Their imputation of hatred in others, it would seem, is mass-projection, a reflection of something dark in their own passions. Given the enormous political force this phenomenon wields, it is incumbent on us to identify its source and who has signed onto it.

The Essence and Imperialism of Hate

A good place to start our journey into hatred is the Roman Catholic Church. My reasons are not to join the voices who over the centuries have condemned Christianity for acts of intolerance and historical injustice, or even those in the liberal camp who profess admiration for the now-commonplace separation of Church and State. Instead, I want to suggest that it is the Church which stands at the intellectual and historical fulcrum of much of our understanding of hate in the West. And that there are two relevant ideas associated with the Church in this regard: essence and empire.

First, though, I want to draw on a statement from the late head of the Roman Church, Pope Francis. Often considered a leading figure from the Church’s progressive wing, even Francis, in the annual speech delivered to diplomatic representatives to the Holy See on January 10, 2022, found himself lamenting a scourge of the left. A “divisive” mindset, he bluntly asserted, has taken hold in many institutions, driven by a movement “that rejects the natural foundations of humanity and the cultural roots that constitute the identity of many peoples.”

Coming to the nub of the matter, the late Pontiff went on to say, “I consider this a form of ideological colonization, one that leaves no room for freedom of expression and is now taking the form of the ‘cancel culture’ invading many circles and public institutions.” [Emphasis added] This is a remarkable statement because, not only does it condemn cancel culture, it provides an intellectual framework for thinking about it. While his speech went on to explore this problem’s implications, we need to unpack the phrases cited above.

Beginning with the notion of the “natural foundations of humanity,” we see two linked ideas at work. The first is what is true by nature. Francis evoked the long history of Catholic theology and its adoption of philosophical categories. To understand what is true by nature traditionally has meant to understand, or attempt to understand, what is universally true and accessible to human reason as opposed to defined by custom or law; in other words, to understand what is essential to each category of thing. What is natural is also universal, having the same essence everywhere regardless of differences of culture, politics and language. Universalism as essence is the second idea linked directly to nature.

In the same breath, Francis invoked the particularity of culture that differentiates the diverse peoples who constitute the universal that is humanity. Here again, Francis harkened back to the long intellectual tradition in which the Catholic Church sought to understand the relationship between what is universal and what is particular, between what is essential by nature and what exists concretely.

Over against this interplay of essential nature and particular cultures, the pope condemned cancel culture as a form of “ideological colonization” that, first and foremost, “leaves no room for freedom of expression.” Here again, there is a lot to think about. The phrase “ideological colonization” is highly evocative. We have come to recognize, following bitter experience during the 20th century, that ideology has a negative connotation implying force, destruction and exclusion. To mark something with the qualifier of “ideological” is not complimentary.

We know we are in odd times when the Catholic Church, once the critic of many political rights, must come to the rescue of those same political rights against the forces of the left and postmodern cancellation.

Similarly, “colonization” in current parlance has become the ultimate sin. To colonize is to dominate, to subjugate and to exploit – even to eliminate. Additionally, we often associate colonization with imperialism, including the imperialistic notion that we can subsume all peoples under one ruler. In the case of cancel culture, Francis seems to say that it involves precisely this sort of subjugation of difference – an imperialism that brooks no exception.

Helpfully, he also tells us what an exception to this ideological colonization might look like: a freedom, specifically the freedom of expression. This is interesting because the pope introduces something not explicitly part of the Church’s long intellectual tradition: freedom of expression. We generally think of freedom of expression as one of the original political rights, one often exercised against the Church’s authority.

Today the Catholic Church has, after a long battle against modernity, taken to championing this most modern of human rights. But according to Francis, it is exactly this one that cancel culture seeks to deny. We know we are in odd times when the Church, once the critic of many political rights, while also having been the font of broader human rights, must come to the rescue of those same political rights against the forces of the left and postmodern cancellation.

The late pope used a notably precise phrase when describing cancel culture’s attack against freedom of expression: it “leaves no room.” Cancellation as imperialist colonizer has the totalizing effect of eliminating dissent or disagreement. This is effectively to eviscerate and obliterate, to erase from existence. That it will do so in the name of “diversity” and call those who disagree “hateful” shows how far we have fallen from what the Church might call, somewhat ironically, grace.

The second point to consider is where we are today. Those who most willingly deploy cancellation as a tactic against what they see as the oppression of ancient authorities such as the Catholic Church routinely deplore any reference to what is true by nature, to what is essential. They view such terms as carriers of and justifications for the imposition of repressive formalism onto the fluidity of diversity, the curse of “essentialism”. Similarly, they vehemently decry imperial colonialism as an effort to erase cultural difference, as the ultimate expression of “hate”.

That said, this is one of those instances when the postmoderns object too much because today’s left – the radical left that labels all dissent as hateful – is itself consumed with a virulent essentialism that reduces all history and politics to the sole motivation of domination by the West, replete with its accompanying litany of sins from racism and sexism to transphobia and Islamophobia. This is essentialism on steroids, obliterating as Pope Francis noted the diversity of cultures and the individual’s freedom of expression.

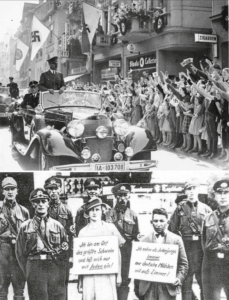

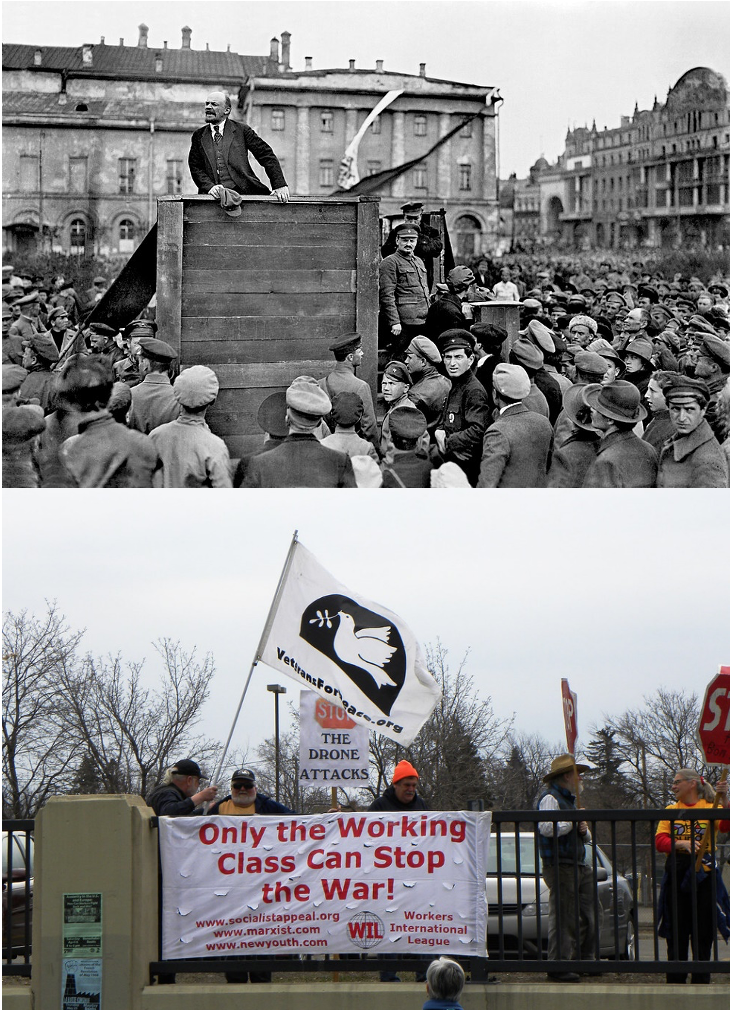

Essentialism on steroids: While decrying imperial colonialism and so-called “essentialism” – a snide term for the age-old philosophical and theological idea that every category of thing (including humans) shares an innate, universal essence – the postmodern left has adopted a reductive and all-consuming attitude that all historical events and political movements can be explained by the West’s hatreds. (Sources of photos: (left) Instagram/activistnyc; (right) Unsplash)

Essentialism on steroids: While decrying imperial colonialism and so-called “essentialism” – a snide term for the age-old philosophical and theological idea that every category of thing (including humans) shares an innate, universal essence – the postmodern left has adopted a reductive and all-consuming attitude that all historical events and political movements can be explained by the West’s hatreds. (Sources of photos: (left) Instagram/activistnyc; (right) Unsplash)Concurrently – and perhaps partially as a result – we find ourselves surrounded by imperial or, if you like, imperial-adjacent structures, including those that colonize the mind in the form of postmodern, critical and gender ideology. Despite their anti-colonial rhetoric, entities such as the United Nations and the European Union as well as related movements and organizations are aggressively imperial in their form and behaviour, and, some would say, objectives, as evidenced by their disdain and even hatred for the inherent diversity of nation-states. This helps explain why the radical left’s version of hate often joins hands with the imperialism of political Islamism as it seeks to reinvigorate the universal caliphate – two fundamentalisms working in concert and inspired by the same postmodern ideology.

What is the connection between cancel culture and the concept of “ideological colonization”?

Cancel culture is a prominent manifestation of what the late Pope Francis described as an “ideological colonization” by the woke-left that invades public institutions and leaves no room for freedom of expression. This movement rejects the natural foundations of humanity and the cultural roots that constitute the identities of many peoples, seeking to replace individualism with a totalizing intellectual imperialism. By labelling any disagreement as hateful, it not only forcefully imposes its view but effectively seeks to negate the inherent diversity of cultures and the freedom of individuals to express themselves.

Celebrate All Identities – Except One

Hatred is something fairly easy to identify in action but more difficult to define in general. We might hate a person who has personally wronged us in a significant way. Some of us could hate someone who is richer or more powerful, or a rival in business, academe or love. Hate is often directed at an enemy in war. In all these instances, hate as an experience is readily understandable and relatable, even if disapproved of, as a visceral dislike of another individual or group of people. And we know that it can lead to hostility that can in turn become violent.

Hate also has a more complex meaning. With the 20th century’s rise of human rights as formally propounded ideas we came to equate hate with prejudice, bad or hateful, because it imposed an unjust limitation on individuals due to their accidental characteristics. When we say “accidental characteristics” nowadays, we tend to include everything from race and sex to religion. But while it is clear, or was until recently, that race and sex are not chosen, religion is subject to some degree of choice, so we should treat religion as a subjective preference more than an objective obligation. The overall point is that our liberal-democratic notion of rights implied that all individuals are worthy of respect irrespective of their particular identities.

Today’s left claims to despise both essentialism and imperialism in the name of recognition of identities. And in its own exclusive vehemence, it labels anyone who does not uniformly share its totalizing views as ‘hateful’. This is the ironic essence and imperialism of the left’s own uncompromising hate.

That has changed dramatically in the 21st century. In an inversion of past liberal indifference to identities, we now celebrate differences as the hallmark of each individual’s self-understanding. Moreover, these identities are apparently subject to change as they have come to be regarded as fluid and, for some, actually in flux. In this context, we no longer simply respect others as individuals but are obligated to recognize, accept and even praise their individual identity choices. And as if this relativist notion of recognition were not enough, we attach to it the affirmation that the basic Western identity of liberal free-market individualism has been the historical oppressor of all other identities.

In a more philosophical vein, we might say we merge Friedrich Nietzsche’s dismantling of objective truth via Martin Heidegger with Karl Marx’s essentialist notion of the oppressor-oppressed binary. To hate in this context is to define and rank identities, especially if that ranking gives any priority to the vast array of affiliations that make up the complex history of the West. We celebrate the category of identity but we detest any authority that may arise in relation to particular identities, what Hegel referred to as Sittlichkeit, or the moral contents of life. This links us to the essentialism and imperialism of the contemporary rhetoric of hate as identified and deplored by Pope Francis.

Today’s left claims to despise both essentialism and imperialism in the name of recognition of identities. And in its own exclusive vehemence, it labels anyone who does not uniformly share its totalizing views as “hateful”. This is the ironic essence and imperialism of the left’s own uncompromising hate. And here we can point out that today’s left is collectively driven and consumed by hatred in a way very unlike the right, where hatred remains the province of individuals and smaller sub-groups – at least for now – and where political opinions and positions are formed for the most part by ideas, facts, evidence and emotions other than raw hatred.

A Brief History of the Good – Human and Divine

As I’ve mentioned, the idea of an essence – something that has universal applicability apart from particular entities – is commensurate with the search for the natural foundations of human existence and political life. What do I mean by this? Looking at the original Ancient Greek philosophers, they concerned themselves constantly with whether there was an unchanging truth and, if so, how it related to the particularity of existing things, be they humans, animals or inanimate objects.

Heraclitus thought there was only change and flux. Parmenides took the opposite position and argued that only universals were real while particular beings were illusory. Later thinkers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, often in political debate with the materialistic Sophists, sought something of a middle way that took account of the aspiration for knowledge of universals while recognizing the sway of particularity. They took various approaches on this front, often replete with their own difficulties. It is, after all, virtually impossible to pin down Plato on his final view of universals as ideas (his theory of “forms”), if he even had one, given that he describes them differently depending on the interlocutors in his dialogues.

The key point is that philosophy, differentiating itself from particular political communities, came to see the universal as the goal of understanding. At the same time, while it often attributed impediments to understanding to the particularity of bodily and partisan passions, it did not simply disdain non-philosophic goals. In fact, it considered most human endeavours as goods in themselves that needed to be balanced.

A prime example of this is how Aristotle deals with the competing aspirations of aristocrats and democrats in Chapter Three of his Politics. Having attempted and failed to discuss these two classes according to their natures and according to their interests in the previous two chapters, in Chapter Three Aristotle follows a sort of mediation between them. Significantly, he treats both classes as seeking to rule according to the competing goods they espouse.

Aristocrats desire to rule based on the principle of virtue (though that has really degenerated into wealth by Aristotle’s time; his aristocrats are oligarchs). By contrast, democrats seek rule based on the idea of equality. Aristotle proceeds to point out to both parties that there are inconsistencies in their conceptions of the good, thereby seeking to moderate their differences, something that occurred every day in each of the various Greek cities. What remains important here is that, for Aristotle, these competing interests are not just interests but desirable goods in themselves; as such, they all have a legitimate though partial claim to rule within the human whole that (in the Ancient Greek mind) is the city-state.

In his famous Politics, Aristotle described the different principles and competing aspirations of two societal classes, aristocrats and democrats, as desirable goods in themselves – which thus provided each with a legitimate though partial claim to governing their city-state. Pictured, Croesus Showing His Treasures to Solon, by Gaspar van den Hoecke, 1630s. (Source of image: Radio France)

In his famous Politics, Aristotle described the different principles and competing aspirations of two societal classes, aristocrats and democrats, as desirable goods in themselves – which thus provided each with a legitimate though partial claim to governing their city-state. Pictured, Croesus Showing His Treasures to Solon, by Gaspar van den Hoecke, 1630s. (Source of image: Radio France)As philosophy and political history wind their way through the demise of the Greek cities, Alexander the Great’s empire, the rise of the Roman Republic and its transformation into the Roman Empire, Aristotle’s subtle treatment of human goods as well as Plato’s politically attentive philosophy undergo changes. These are especially apparent in terms of how a more universal society such as an empire deals with the particularity of class and nation. This question is reflected for example in Cicero’s thought.

Following the Roman Empire came the unique rise of universal revealed religions that again changed the interaction between a universal God and the diminished panoply of goods Aristotle and Plato were so attentive to. Now, each of the three main revealed religions, leaving Zoroastrianism aside, approached this differently. Ancient Judaism, while universalist in intent, manifested this through the Jews as a chosen people, a light unto the nations. Islam, which wholly embraced imperialism as it expanded out of Arabia, incorporated political and sensual goods into its understanding of eternal reward for submission to God’s will. This led Medieval Christian critics to view Islam, despite its protestations, not as a monotheistic religion at all.

Christianity absorbed Western philosophy and, in accord with its doctrinal approach to faith, distinguished between itself and what eventually was called the secular realm. This was most famously expressed in the instruction by Jesus in Matthew 22:21 to “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” It was this distinction that went on to drive so much of European history in the form of the conflict between emperors and kings on the one hand and the church and its hierarchy on the other. It also proved critical in the development of individual political rights and the construction of the liberal-democratic order as it opened a secular space for the modern emphasis on the individual.

The impact of Christianity proves manifold and wide-ranging, as well as somewhat contradictory. On the one hand, it seeks an intimate relationship with God and among fellow Christians that is more intense than the intimacy of the small Greek cities. Hence Saint Augustine’s use of the phrase “City of God”. On the other, it models its hierarchy on imperial Roman offices and claims a universalism even more extensive and less territorially limited than the once-massive Empire. Similarly, while it recognizes and to some extent respects the range of human goods, its emphasis on the unique and infinite good that is Salvation necessarily demotes the others.

This is the fulcrum that Christianity represents in our Western history. The Christian distinction between this world and the next, between the relative worldly goods and the absolute eternal good, becomes the ‘problem’ that modern political philosophy will seek to overcome.

What remains similar between Christianity and its philosophical predecessors is the notion that particular passions detract from the higher goals of understanding and Salvation. Christianity adds the notion of sin to the failures of intellect as a cause of evil in the world. Where the non-philosopher in the ancient milieu simply lacked the intellect to understand the good, the individual now has the added problem of a will corrupted by sin. When taken to extremes, as it can be in more fundamentalist versions of Christianity, the human goods themselves become hateful because they are objects and triggers of sin. So where we once saw love of family and nation as desirable forms of loyalty and patriotism, extremist elements, both philosophical and religious, turn these forms of love into hate.

While late Medieval thinkers advise prudence in such a situation, the political fallout, as Dante portrays in the Inferno, will prove unsustainable. This is the fulcrum that Christianity represents in our Western history. The Christian distinction between this world and the next, between the relative worldly goods and the absolute eternal good, becomes the “problem” that modern political philosophy will seek to overcome.

How did the theories of Niccolò Machiavelli change politics in Western society?

In the early 16th century, Niccolò Machiavelli introduced what he called “new modes and orders” to political philosophy that ended up writing hatred into the fabric of Western political life. He discarded the Classical and Medieval traditions of seeking universal essences, focusing instead on the effectual truth of how people actually live and states actually operate. On the positive side, this provided a large step on the West’s journey to philosophical and scientific empiricism. But by framing political relations as simply raw power ratios in which an elite desires to dominate/control while the popular classes seek to escape their oppression, Machiavelli replaced the possibility of compromise in pursuit of a common good with a permanent state of discord.

The Efficacy of Hate

Into this tangle steps Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli. The early 16th century Florentine thinker – also a great reader of Dante – reworks the intellectual and political inheritance he received to introduce what he in the Discourses on Livy called “new modes and orders”. For this he is generally recognized as the founder of modern politics as well as modern political science. Two things he does are worth noting for our purposes. First, he directly attacks the Classical and Medieval notions of universals and essences. Second, he writes hate into the very fabric of political life.

Machiavelli took direct aim at Aristotle and the entirety of his philosophy, though in a political rather than metaphysical register. In the famous 15th Chapter of The Prince, in a discussion about what rulers rightly should be praised and blamed for, Machiavelli writes:

“But since my intent is to write something useful to whoever understands it, it has appeared to me more fitting to go directly to the effectual truth of the thing than to the imagination of it. And many have imagined republics and principalities that have never been seen or known to exist in truth; for it is so far from how one lives to how one should live that he who lets go of what is done for what should be done learns his ruin rather than his preservation.”

These few lines contain in them a whole new world. As Machiavelli notes, the tradition in writing about political matters, including in the mirror-of-princes genre that our Florentine claims to employ, is to describe theoretical models of a well-governed polity rather than look to existing political institutions for guidance. Aristotle did write about some existing political structures and arrangements, but these reviews were intended to glean what would be the best form of polity – and that was too much for Machiavelli. He had little interest in the imagined republics and principalities of the Greeks or their Roman or Christian successors. So he declines to propound upon how one should live, preferring to study and learn from how one does live.

But Machiavelli isn’t just talking about politics here. He is also making a philosophical statement that, in those few words above, throws overboard the whole panoply of Classical philosophy and Medieval theology built around the notion of a universal essence as comprehended by the imagination. In doing so, he also casts aside the concern with the relationship between universal essences and existing particulars. For Machiavelli, general intimations of immediate applicability drawn from how politics actually works replaces pontificating about idealized realms. In this, he sets the groundwork for the following centuries’ emphasis on science as the practical application of natural laws.

Machiavelli’s revolution will carry through all of modern philosophy to our own time. John Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding will claim that we have no access to universals, including any essential answer to the age-old question: What is man? He instead invokes the functions of the state of nature as a framework to establish the sovereign power as well as limit it according to the right to own property. Locke’s empiricist critic, David Hume, will even discard the right to property ownership as an over-complex idea beyond human certainty.

Immanuel Kant will then attempt to reintroduce moral norms into human affairs, but not by returning to human nature. Instead, Kant limits the newfound science of the laws of nature in order to preserve room for a new human freedom to legislate. This will spawn a series of reactions leading to the rejection of Kant’s project by Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger and the last great movement of modern philosophy: existentialism.

For Nietzsche and his acolytes, even Kant failed to eliminate the spectre of essences. So they attempt to overthrow, once and for all, the decayed remnants of Plato’s essentialism and its popularized Christian manifestation that they believe have led Europe to the contemporary nihilism (abstract detachment) of Kantian moralism. They engage in an endless form of resistance, invoking the particular as a manifestation of will to power (Nietzsche) or as a rather unfathomable revelation of Being (Heidegger).

Continuing Machiavelli’s revolution, modern German philosophers (top left to right) Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger moved ever-further from Platonic and Christian notions of universals and focused on human particularities such as the “will to power” and “higher man”, all-but completing the West’s march into nihilism and totalizing ideology. Shown: (bottom left) The Scream, by Edvard Munch, 1893, often associated with nihilism due to its theme of existential terror; (bottom right) exhumed bodies of some of the 800 slave labourers murdered by Nazi SS guards near Namering, Germany, May 1945. (Sources of photos: (top right) Willy Pragher, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0; (bottom right) Marion Doss, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

Continuing Machiavelli’s revolution, modern German philosophers (top left to right) Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger moved ever-further from Platonic and Christian notions of universals and focused on human particularities such as the “will to power” and “higher man”, all-but completing the West’s march into nihilism and totalizing ideology. Shown: (bottom left) The Scream, by Edvard Munch, 1893, often associated with nihilism due to its theme of existential terror; (bottom right) exhumed bodies of some of the 800 slave labourers murdered by Nazi SS guards near Namering, Germany, May 1945. (Sources of photos: (top right) Willy Pragher, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0; (bottom right) Marion Doss, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)The problem is that this entire modern effort seems to have failed. As noted above, our contemporary thinkers – postmoderns like Michel Foucault, critical theorists in the vein of Herbert Marcuse, third-wave gender feminists like Judith Butler and anti-colonialists like Frantz Fanon and Edward Said – while ostensibly rejecting the imperious notion of universals, reassert a viciously uncompromising new universal that combines unqualified relativism with neo-Marxist oppression narratives. For the contemporary left, any diversion from this essentialism is a form of hatred warranting total silencing through cancellation.

Machiavelli did something else: wrote hatred into politics. What does this mean? Recall that Aristotle addressed the conflict between Greek aristocrats and democrats by treating both classes as seeking to rule based on their particular notion of the good. Machiavelli changes the dynamic, setting the democrats against the aristocrats. Rather than two classes seeking to implement their own notion of the good as rulers, which allows at least the possibility of compromise through discussion, Machiavelli treats them as entirely distinct, eliminating the very idea of their claim to rule as goods and instead highlighting the power ratio between them.

Machiavelli introduces discord into our modern thought and the political arrangements built on it. And in our contemporary world, what liberalism once moderated has been turned into a hammer to attack the West and all the structures it has come to value, from family and religion to freedom, merit and science.

The aristocrats’ sole desire is to dominate and oppress the popular classes – not merely rule the state. The democrats’ program is encapsulated as an effort to escape the aristocrats’ tyranny and oppression. They no longer have their own notion of the good but exist solely as negation, repudiation of the powers that be. In Machiavelli’s world, it falls to the prince (later elevated by Thomas Hobbes to the infamous “Leviathan”) to manage and exploit this conflict.

Whether we consider the Greek philosophers, the Romans or the Medieval Christian thinkers, regardless of their differences in emphasis on the essential nature of the good and how it relates to other lesser goods, we see none attempting to build hate and conflict into their thought, let alone activate it for political effect.

In doing so, Machiavelli introduces discord into our modern thought and the political arrangements built on it. Many of his followers have attempted to moderate this influence. But in our contemporary world, what liberalism once moderated has been turned into a hammer to attack the West and all the structures it has come to value, from family and religion to freedom, merit and science. As well as the nation-state, the carrier of our liberal-democratic adventure for at least four centuries.

The Left’s Imperial Contempt for the Nation

The nation-state is not an obvious political entity. For most of history, most humans have lived in empires of various types, from the more national empires of the ancient world (Egypt, Babylon, Assyria, China, Maya, etc.) to the multi-civilizational empires beginning with Persia and followed by Alexander’s and then the Roman. Apart from prehistoric small bands and then tribal formations which are partly political, the only other political entity of note is the city-state, which has had some moments of greatness, especially among the Greeks and in Italy and northern Europe, but has generally been limited in scope and duration.

The nation-state only came into its own in 17th-century Western Europe. It is a particularly complex entity. Partly natural and partly invented, it arose in the context of Western Christianity. According to Hegel and some rabbinical thinkers, the nation concept allowed Europe to subjectively appropriate Christianity, meaning the objective requirements of the imperial Christian Church were appropriated by various free peoples within a national structure. The results were, first, a welcome settling-down of the chaotic barbarian wanderings during the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire, second, a lot of religious conflict as various nations each claimed to represent the “one true Church” and, more happily, the development of our modern nation-states as liberal, democratic, economically inclusive and pluralist (non-sectarian).

Today, however, the left – both ideological “progressives” and globalist liberals – has turned against the nation in favour of a new form of multi-civilizational imperialism. Pseudo-imperial structures such as the EU and UN, supported by various transnational or global organizations, aim for a world under the empire of international law and moralism, leaving behind the retrograde and troublesome nation-states that, to their minds, have caused so much conflict.

These new imperialists forget that the nation-state was the exclusive venue in which our liberal democracies were born, thrived and displaced the old autocracies. The new imperialists like to tell us how “democratic” they are. Their democracies are no longer liberal, however, but what I have elsewhere termed “prosecutorial”. In the place of meaningful citizen participation and open debate, i.e., genuine self-government, we are subjected to a range of managerial and administrative procedures overseen by experts who consciously evade input from whom, in occasional moments of clarity, they will term the “deplorables” or “bitter clingers”.

Among the most obvious and powerful contemporary manifestations of the new imperium is the endless effort to define and persecute “hate speech”. It is also here where the left, carried by its own essentialist hatred of any diverging opinion, unites with globalist liberals who show such benign complacency in the face of truly violent hatred of the kind that gave us the Bondi Beach massacre. They share an imperial hatred for the nation-state, both believing it should pass into history as we create the new utopia of either global management or, ironically enough, tribalist violence, although very few put it in such stark terms. And anyone who challenges this even indirectly finds the label of hateful, racist, transphobic, etc. dumped upon them.

The nation-state developed within the framework of Western Christianity in the 1600s; though intense religious conflicts ensued as various nations claimed to represent the “true” Church, these were eventually superseded by modern states defined increasingly by liberalism, democracy, economic inclusivity and pluralism. Pictured: (top) Wallenstein: A Scene of the Thirty Years War, by Ernest Crofts (1847–1911); (middle) ratification of the Treaty of Münster, part of the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, by Gerard ter Borch; (bottom) the UK House of Commons Chamber, February 2024. (Source of bottom photo: UK Parliament/Maria Unger, licensed under CC BY 3.0)

The nation-state developed within the framework of Western Christianity in the 1600s; though intense religious conflicts ensued as various nations claimed to represent the “true” Church, these were eventually superseded by modern states defined increasingly by liberalism, democracy, economic inclusivity and pluralism. Pictured: (top) Wallenstein: A Scene of the Thirty Years War, by Ernest Crofts (1847–1911); (middle) ratification of the Treaty of Münster, part of the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, by Gerard ter Borch; (bottom) the UK House of Commons Chamber, February 2024. (Source of bottom photo: UK Parliament/Maria Unger, licensed under CC BY 3.0)This imperial impulse, combined with the essentialism of hate we’ve discussed, allies with another actor on the contemporary world stage, though as I’ve learned personally, to speak about it can result in nasty consequences. This is the violent imperialism of politicized Islamism. As noted earlier, Islam took on the imperial political form as it broke out of the Arabian Peninsula. Finding itself fighting weakened versions of the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire and the much-reduced heirs to the Persian, it conquered spectacularly, carrying the Arabic tongue with it. The political form it relied on was the caliphate, which combines political and religious rule under one supreme leader.

The history of Islamic expansion – often by the sword but sometimes by conversion and trade – is too complex to go into here. What we can say is that the last caliphate in the form of the Ottoman Empire was purposely replaced in 1924 by Mustafa Kamal (the later Atatürk) in favour of the modern Turkish nation. Since then, traditionalist Muslim forces, influenced ironically by the Western philosophy of repudiation, have sought to rebuild a stricter and more violent version of the imperial caliphate than any known to history. This effort began with the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928 and continues today in the Islamic world and via the phenomenon of “entryism” in the West. That so many Middle Eastern and Muslim nations, from Jordan and Egypt to Bahrain and the UAE, condemn these efforts should alone tell us they are a danger to freedom and peace around the globe.

From well-known figures like Jordan Peterson and Amy Hamm to uncounted and unheralded targets such as school trustees who oppose transgender ideology or city councillors who question the constant reading of land acknowledgements, the dominos have fallen from coast to coast. And continue to fall.

This goes a long way to explaining why the contemporary left, enamored of its own imperial and essentialist hatreds, has such an affinity for Islamism’s imperial ambitions as professed by the Islamic Regime in Iran and its proxies in Lebanon and Gaza. It also accounts for the fact that the radical left has no interest in freeing the Iranian people from the dictatorial theocracy. This regime was itself inspired by Ari Shariarti, an intellectual follower of Heideggerian thought, and Michel Foucault, who made pilgrimage to Iran in 1978 to praise the Islamic revolution that gave the world this current thugocracy.

What about Canada?

Canadian readers should have little trouble applying the foregoing discussion’s philosophical and, at times, perhaps somewhat abstract framework to the all-too-real, hateful imperialist essentialism of Canada’s left. “Progressives” throughout Canadian society have proved highly susceptible to the pathology of hate and, once in its grip, enthusiastic and disturbingly successful practitioners of its precepts.

Why is the nation-state the essential venue for the survival of liberal democracy?

The nation-state, which rose to prominence in 17th-century Western Europe, provided the exclusive venue in which liberal democracies were born, thrived and displaced old feudal autocracies. The nation-state allowed free peoples to build democratic processes and establish modern political rights within a national structure that was economically free and pluralist. This great experiment in individual liberty, meritocracy and legal/political equality is now threatened by new universalist institutions, such as the United Nations, European Union and similar-minded organizations which seek to delegitimize the nation-state as parochial, racist or hateful.

From well-known figures like Jordan Peterson and Amy Hamm to uncounted and unheralded targets such as school trustees who oppose transgender ideology or city councillors who question the constant reading of land acknowledgements, the dominos have fallen from coast to coast. And continue to fall. In examining the phenomenon for a written critique, one finds not merely a target-rich but target-saturated environment. Such is the hatred of the left, the hatred of uncompromising essentialism bound up with intellectual imperialism that, as Pope Francis correctly noted, “leaves no room” in its exclusionary obsession.

An especially egregious – and illuminating – Canadian example of this hatred in action will be the subject of a planned upcoming essay.

Collin May is a lawyer, adjunct lecturer in community health sciences with the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, and the author of a number of articles and reviews on the psychology, social theory and philosophy of cancel culture.