Please go here for Part I.

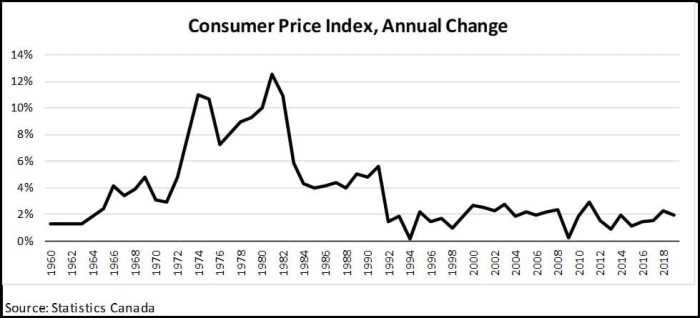

Canada followed conservative monetary policy throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, which kept the money supply and, in turn, inflation in check. But after a near-defeat in the 1972 election, the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau embarked on a massive spending spree lasting the rest of the decade that stoked inflationary pressures while deliberately keeping interest rates low. The result was an explosion of inflation, little or no real economic growth, and persistently high unemployment – the ugly confluence of “stagflation” that plagued Canada and much of the First World during the late 1970s. This time is known today as the Great Inflation. Although governments in the 1980s did somewhat better it wasn’t until the early 1990s that inflation was finally tamed.

As politicians, economists and the public painfully learned during this era, the only proven cure for inflation is to tighten (or reduce) the money supply by raising interest rates or turning off the printing presses. This understanding that inflation is always a ‘monetary phenomenon’ – that it is inexorably linked to the growth rate of the money supply – has formed the basis of conventional monetary economics ever since.

In countries that have suffered crippling hyperinflation, it becomes necessary to remove the debased currency entirely from circulation. Post-Second World War occupied-Germany’s currency reform of 1948 (the “Währungsreform” for Germanophiles) issued one new Deutsche Mark for every 20 old Reichsmarks. This commitment to tight money policies is widely considered to have laid the foundation for the new country of West Germany’s famous “economic miracle” by which the federal republic soared from basket case to Western Europe’s main economic engine in under 20 years. Putting an end to inflation is widely accepted as a necessary precondition for long-lasting prosperity.

Lately, however, the prospects for a revival of damaging inflation have been greatly enhanced by the trendy new notion of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Adherents of MMT argue that, contrary to conventional wisdom, massive government spending no longer poses a significant financial burden because as long as a government borrows in its own currency a central bank can simply “create” more of it through the printing press. Because it seems to offer a magical way to finance any project, however grand, MMT has gained considerable popularity among economically-challenged progressive politicians. Socialist New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, for example, has embraced the idea of MMT as a way to pay for her “Green New Deal” – a spending program that could cost more than US$6.6 trillion annually.

“I won’t be the one paying for all this,” says U of T economist Carr, who has retired from active teaching. “It’s future generations who will have to pay the cost of both high inflation and high debt loads. It will be my children and their children who bear that burden.”

MMT has been roundly criticized by most serious economists as entirely unworkable. A recent survey of several dozen leading academic economists unanimously agreed MMT could not work as promised, and even Paul Krugman, arguably the most influential left-of-centre economist in the world today, has called the concept “obviously indefensible.” The problem with MMT, says Jack Carr, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Toronto and an expert on monetary policy, is that it claims to offer a “free lunch” by promoting “the idea that you can spend whatever you want without consequences.” And the most serious consequence of endorsing MMT, Carr declares, is runaway inflation caused by a massive increase in the money supply.

Could the dramatic growth in government Covid-19-related debt and the eagerness of some politicians to ignore conventional monetary theory in favour of MMT’s fantastical appeal reincarnate the Great Inflation? Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist at the IMF, considers a renewed period of globally high inflation possible if certain conditions are met. This includes a massive hike in debt-to-GDP ratios and a willingness among politicians to twist central banks to their will. With Canada’s federal government looking at a deficit of at least $252 billion – nearly an order of magnitude larger than previously expected – and with the United States government having passed $2 trillion in “stimulus” spending already, the first condition is already well on its way to being satisfied.

As for the second condition, in describing a potential American high-inflation scenario, Blanchard writes:

“The government might be tempted to ask the [U.S. Federal Reserve] to keep the interest rate low, so as to decrease the debt burden. While today’s Fed would not yield to such pressure, a future Fed, with a chair appointed by a populist president, might be more willing to bend and keep rates low for too long, leading to overheating and inflation.”

While Blanchard assigns a low likelihood to this eventuality, other analysts believe high inflation is a much stronger possibility once the current pandemic passes. Economist Tim Congdon, chair of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham in England, recently warned Wall Street Journal readers to “Get Ready for the Return of Inflation.” Congdon writes that, “It is reasonable to assume that by spring 2021 the quantity of money will have increased by 15 percent and possibly by as much as 20 percent…outpacing the previous peaks in the inflationary 1970s.” And, as described in Part I, when a country’s supply of money grows at a rate faster than its economy, the value of the currency generally drops. That’s inflation, and it is why inflation isn’t “caused” by higher prices; instead, higher prices reflect the monetary dynamic and are the consequence of bad monetary policy.

In Canada, economists writing for the C.D. Howe Institute have similarly expressed concern over the Bank of Canada’s actions during the coronavirus panic. The central bank’s unprecedented program of purchasing government and private bonds to inject liquidity into the economy caused Canada’s official “money supply” (under its most narrow technical definition) to shoot up from $89 billion on March 11 to almost $227 billion on April 8. Such an unprecedented move creates the potential for a “highly inflationary” scenario, they warned, despite the fact inflation is currently quite low. To prevent this, another set of C.D. Howe economists has recommended a strict commitment to Canada’s traditional “inflation target of 2 percent so that confidence is maintained in Canadian dollar debt.”

If the economic downturn proves to be short-lived, Carr, who professes himself to be an optimist, predicts that all the excess money injected into the system in recent months can be quietly withdrawn by the Bank of Canada (by selling rather than buying bonds or through other means) without stoking inflation to dangerous levels. But, he warns, “If the downturn lasts a year or more and central banks keep buying up government bonds and keep priming the pump − then at some point we’ll see inflation rearing its ugly head again.”

That could mean a return to constantly fluctuating price levels, double-digit interest rates and a huge burden shifted to younger generations. “I won’t be the one paying for all this,” says Carr, who, at 75, has retired from active teaching. “It’s future generations who will have to pay the cost of both high inflation and high debt loads. It will be my children and their children who bear that burden.”

Option 3: Tax the Rich! (Plus all the Rest of Us)

If Canada’s federal government chooses not to repudiate its debt – either openly through default or surreptitiously via inflation – it has two other ways to pay it all back honestly. To generate the cash necessary to balance its budget so that the debt doesn’t grow further, and perhaps even to run annual budgetary surpluses so that some of the existing debt can be paid back, Ottawa and the debt-ridden provinces can either increase revenues or reduce expenses. This means higher taxes, lower spending or some combination of the two.

With Canada’s tax load already comprising 45 percent of national income before the pandemic hit, there’s scarcely any room for new taxes to pay for the Covid-debt regardless of may be expected to bear the burden.

The question of how best to bring public budgets back into balance is a key issue of political economy. And the answer tends to depend on whether one focuses on the first or second half of that phrase. The political response is often to prefer new taxes because this seems easier to carry out and more salutary to a party’s re-election chances. It is widely believed voters will support taxes at the ballot box if they believe only other people have to pay them. The standard response from economic theory, on the other hand, is to prefer spending cuts.

To date, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has shown no interest in austerity and considerable enthusiasm for new taxes. After their 2015 federal election victory, the Liberals managed to turn a balanced budget inherited from the previous Harper government into a $2.9 billion deficit, and then produced a $19.0 billion deficit the next fiscal year. They have run large deficits ever since; as a result Ottawa has been producing red ink continually since the financial crisis of 2008-09.

As for taxes aimed at other folks, as part of their middle-class tax cut in 2016 the Liberals upped the rate applied to personal income over $200,000 by 4 percentage points to 33 percent. In some provinces, this pushed the total personal income tax rate for top earners past 50 percent, a level many economists consider an important threshold in terms of prompting adverse behaviour by taxpayers. As expected, according to the C.D. Howe Institute the Liberals’ “one-percenter” tax hike had an entirely perverse impact on government finances. While the tax did bring Ottawa an additional $1.2 billion from the country’s most productive taxpayers – far less than had been originally budgeted – it actually decreased provincial tax bases by a total of $1.3 billion, causing a net nationwide loss due to behavioural impacts.

As satisfying as it may be to demand that “the rich pay” for the coronavirus debt, we can expect similar efforts to produce proportionately disappointing results. And no matter how high taxes are jacked for high-income earners, the resulting flow of cash would amount to a mere trickle next to the annual deficit. With Canada’s tax load already comprising 45 percent of national income before the pandemic hit, there’s scarcely any room for new taxes regardless of who may be expected to bear the burden. Of course, that doesn’t mean Ottawa won’t try.

Option 4: Cut Spending, Take the Hit and See Growth Return

Thankfully, voters are often far more pragmatic about public finances than is commonly assumed. Canadian experience throughout the 1990s offers several powerful examples of politicians who rode to power on a promise to cut spending and pay down government debt – and who then made good on those promises. The trend began in Saskatchewan under NDP Premier Roy Romanow. Facing a looming financial crisis, the Romanow government began cutting spending in 1992, and kept right on cutting, reducing real program spending per capita by 23.4 percent from 1991-92 to 1996-97.

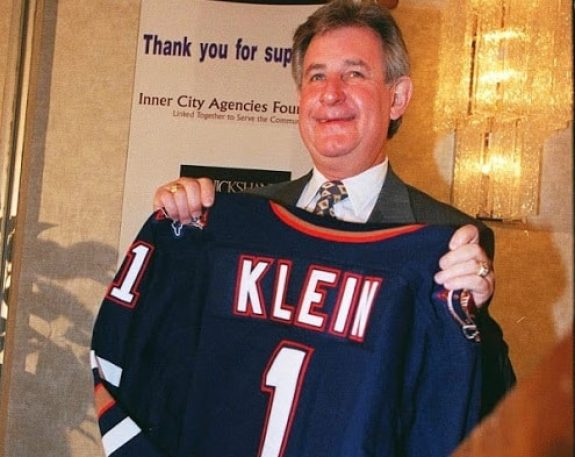

In neighbouring Alberta, after more than a decade of unsustainable spending growth under a previous Progressive Conservative government, new party leader Ralph Klein won the 1993 election with a promise to cut spending by 20 percent. Klein then delivered on that promise. Instead of crushing the province’s economy, Klein’s tough work helped to unleash the greatest economic expansion in Alberta’s history. And instead of sacrificing his career in order to balance the budget, Klein’s popularity soared and he was re-elected to successive majorities. The province ended up not only balancing its budget but paying back all of its debt. Other provincial governments, including the Parti Québécois in Quebec and the Progressive Conservatives in Ontario, similarly staked their political future on spending reductions during the austere 1990s.

And just a month after the Wall Street Journal editorial board was measuring Canada for a pauper’s suit, Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chretien’s government went to work on the federal government’s own fiscal problem. “The debt and deficit are not inventions of ideology,” federal Finance Minister Paul Martin said in his remarkable budget speech of 1995. “They are facts of arithmetic.” Martin made it plain that spending cuts − not tax increases − would do the heavy lifting required to eliminate the deficit.

Feeling the heat from the Reform Party’s incessant focus on fiscal matters, Martin promised Canada a “smaller government.” To do this, he said he was “dramatically reducing subsidies to business”. He also cut transfers to provinces, reformed Unemployment Insurance and halved the budgets of numerous federal departments. In the period from fiscal year 1994-95 to 1999-2000, real federal program spending per capita was reduced by 15.5 percent.

An exhaustive survey led by fiscal policy expert and Harvard economist Alberto Alesina provides additional academic rigour to the question of spending cuts versus taxes. Using a data set covering 16 OECD countries from 1979 to 2015 Alesina, who recently passed away, examined the differing impacts of higher taxes and spending reductions on governments trying to bring their budgets under control. His conclusion: “Fiscal consolidations implemented by raising taxes imply larger output losses compared to consolidations relying on reductions in government spending.” Returning to the same topic last year for the C.D. Howe Institute, Alesina and his co-authors repeated this key result in more accessible terms:

“We find that spending-based austerity plans are remarkably less costly than tax-based plans. Austerity based on spending reduction has, on average, a close to zero effect on output and business investment, and leads to a reduction of the debt-to-GDP ratio. Deficit reduction plans through increasing taxes have the opposite effect: they cause large and long lasting recessions and do not lead to the stabilization of the debt-to-GDP ratio.”

Cutting a deficit via higher taxes can trigger a recession – making everyone worse off – while failing to resolve the immediate problem of government budget deficits and debt. Higher taxes thus fail on every level except, perhaps, political saleability. Cutting a deficit via spending cuts, on the other hand, leads to an immediate improvement on the deficit front and brings down the overall debt, at least relative to GDP, without causing havoc in the rest of the economy.

By avoiding the direct damage of higher taxes while signalling stability and determination to financial markets, spending cuts set the stage for strong economic growth. This is a result that is both intuitive and easily observable. As a result of Martin’s spending cuts, for example, a federal deficit of $38.5 billion in 1993-94 was turned into a surplus of $3 billion in just four years – a stunning achievement that won Martin plaudits from nearly all quarters. The federal government’s net debt-to-GDP ratio fell from 66.6 percent in 1995-96 to 28.2 percent by 2008-09. (After which the spending floodgates burst open once more during the Great Recession.)

More significantly, the sharp reduction in federal government spending made possible a series of tax reductions which – in defiance of Keynesian economic expectations – resulted in strong economic performance led by the private sector. From 1997 to 2007 Canada topped the G7 in both GDP growth and business investment growth. Employment increased significantly faster than in the United States, and the poverty rate fell significantly. In a 2016 interview, Alesina specifically cited Canada as an example of “expansionary austerity” – a real-life case in which a reduction in government spending caused the economy to grow. As corporate profits rose, unemployment fell and incomes grew, government revenues increased as well even with lower tax rates. This was consistent with Alberta’s experience in the Klein era as well.

What Comes Next

The past 25 years of relatively pleasant economic circumstances are very likely coming to an end. And Canadians of all ages need to accept this important reality. It will not be an easy transition. An entire generation has grown up without any recollection of rampant inflation or onerously high interest rates. And while public debt levels have been slowly rising since 2008-09, to date this has had little or no effect on the general tax level or growth. As such, these largely-agreeable times have warped public perceptions of potential economic dangers. Given the massive new accumulation of coronavirus debt, however, it’s highly unlikely this blissful state of affairs will continue for the next quarter century. Now is the time to prepare for some difficult choices.

Trying to cutting a deficit via higher taxes can trigger a recession while failing to resolve the immediate problem of the deficit and debt. Spending cuts, on the other hand, generally lead to a rapid improvement in the deficit without causing havoc in the rest of the economy.

“We weren’t in a great position to weather a big increase in expenditures [before the pandemic hit],” says economist Carr. “The Trudeau government reneged on its commitment to balance the budget and decided it was politically expedient to keep spending, and so deficits have become a permanent problem.” Such profligacy means Canada has less flexibility to deal with new crises as they occur. While he remains an optimist in hoping for a quick recovery, he stresses that the longer the Covid-depression lasts, the more likely we will have to face a serious economic reckoning.

How Canada deals with the massive new debt burden that looms may come to define our economic prospects for a very long time – probably the next decade and perhaps even longer. Stopping payment on the debt, inflating it away or paying it down with higher taxes will, are all options for a cash-strapped government. But all such policies promise difficult times. If the economic consequences of the pandemic linger for a year or longer, Carr expects the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to opt for inflation as the preferred solution to dealing with an out-of-control debt load. “I can’t see this government doing any substantial on spending cuts,” he says. “My thought is that they will go for the inflationary route, print the money and collect their taxes that way.” In other words, a return of the Great Inflation introduced by his father.

In truth, however, the only economically viable solution to restoring our country’s fiscal health, restarting our economy’s growth and avoiding shifting the burden onto future generations is to implement a significant reduction in public spending as soon as practicable. “Governments that resist restoring free enterprise and fiscal responsibility will experience recession and stagnation,” former Prime Minister Stephen Harper wrote in the Wall Street Journal recently. “Those that do the right thing will lead their countries to a far more prosperous future.” It ought to be an easy choice.

Matthew Lau is a Toronto writer specializing in economic issues. With files from Peter Shawn Taylor.