The popular romantic crime TV series Castle, which aired on ABC for seven years until May 2016, was a major hit, compellingly inventive and unfailingly entertaining. Featuring best-selling detective novelist Richard Castle and his NYPD companion Kate Beckett, the series was a tantalizing mix of humour, tension, surreal plot turns and budding romance. After teaming together for several years and negotiating periods of personal friction, the protagonists realize they’re in love, marry and continue working together to solve their frequently bizarre cases.

The narrative often touched upon currently topical subjects, one of which has to do with the mystique of the mask. A sequence of episodes (culminating in Season 7, Episode 15) deals with a psychotic killer called 3XK – he kills in batches of three – and his female associate, a cosmetic surgeon who at one point rearranged people’s faces to resemble and terrify their actual targets, the members of the police homicide unit. That is, the surgeon replaced one person’s face with another’s, a clever twist on a standard motif: masking. In a number of rather harrowing episodes, the baddies kidnap Kate with a view to her literal defacement, scalpel poised for incision. All’s well that ends well as the villains are duly dispatched at the conventionally last moment.

These episodes got me thinking about the real-world transposition of the convoluted story, in particular the relation between response and disfigurement, of how faces are expressions of personality, presumably of one’s essential nature, or at any rate determine how one relates to the presence and character of other people. Though we may sometimes be deceived, we go by the face.

Most of us surely accept without question that it’s near-impossible to fall in love, learn to trust or form any significant attachment to another without visual access to their face. To cover up the face as a diktat of public policy is, therefore, nothing short of a crime against humanity.

References abound in art, literature and song to the beauty and significance of the face. Indeed, the face has many facets. It can be a riddle, almost Sphinx-like, inviting speculation. “There’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face,” states Duncan in Macbeth (Act I, Scene 4), and Lady Macbeth a little later, “Your face, my thane, is as a book where men may read strange matters.” (Act I, Scene 5)

The charm, attraction and allusiveness of the face is a commonplace. One thinks of Milton’s heart-wrenching Sonnet 23, “Methought I saw my late espoused saint,” with its poignant conclusion:

Love, sweetness, goodness, in her person shin’d

So clear as in no face with more delight.

But Oh! as to embrace me she inclin’d,

I wak’d, she fled, and day brought back my night

Or Thomas Campion’s gorgeous “Cherry-Ripe” with its opening lines:

There is a garden in her face

Where roses and white lilies grow

The trope runs ceaselessly through popular music. Where to start? The Monkees’ chart-topper “I’m a Believer,” with its jaunty chorus “Then I saw her face/Now I’m a believer,” is a karaoke favourite, as is Taylor Swift’s lovely “Your Face” and the phrase:

I wish I could close my eyes and see you

I wish the sky had your face

And who can forget the Alan Jay Lerner classic “I’ve grown accustomed to her face,” made famous by Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady, with its wistful ending:

I’ve grown accustomed to the trace

Of something in the air

Accustomed to her face

These are truths that everyone knows, attested to throughout the annals of culture, from Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus where Helen of Troy is memorably portrayed as “the face that launched a thousand ships,” to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 20 in praise of a young man’s face, to the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile and the appealingly waif-like appearance of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, to the endless swoon of the modern entertainment media.

Hollywood capitalizes on the faces of both men and women; female beauty, however, is the crux and mainstay of cultural iconography. Stana Katic, Castle’s Kate Beckett, is one of the most beautiful in the pageant of Hollywood and TV’s sirens; it is no accident that her face enchants her female tormentor. As William Blake chants in “The Divine Image”:

For mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face

Most of us surely accept without question that it’s near-impossible to fall in love, learn to trust or form any significant attachment to another without visual access to their face. To cover up the face as a diktat of public policy is, therefore, nothing short of a crime against humanity.

We know, too, that a face that has been massively scarred or mutilated, its appearance indelibly altered, produces a sense of alienation or horror and – however unfairly – renders that person a kind of stranger, even if one knows him or her well. One reacts to the face not only aesthetically but, so to speak, proprioceptively. The disfigured face is a staple in the horror and sci-fi genres, a device which masks the underlying human likeness of the characters – the living dead, the other-world ghoul, the demon from hell, the interplanetary invader, all or most somehow humanoid but either facially distorted or even featureless. They are, in effect, masked, incommunicable, principals in a veritable zombie jamboree, minus the vivacity.

The mask as a covering is obviously used to conceal culpable identity – the stock-in-trade of the assassin, the bank or convenience store robber, the Antifa thug – or to hide one’s shame, like the disfigured phantom of the opera. It is, of course, used for beneficial purposes as well – the surgeon in the operating theater, the farmer at harvest time, the auto-body repairman, the skier on a cold day, pedestrians in the dense smog of unfiltered cities. And for enjoyment; there is the playful, often half-mask intended to spark the sense of mystery and allure, as in public festivals and private balls. The mask may also bear iconic status, as in the 2006 film V for Vendetta where the Guy Fawkes mask represents revolt against repressive authority – though the authority in question is ideologically ambiguous, if not skewed.

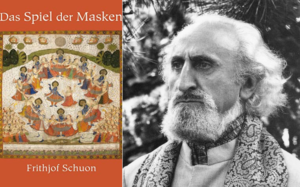

In The Play of Masks, a complex interplay of theosophic speculations, Frithjof Schuon changes the terminology, but the import is the same. What we call the mask he calls the veil, an occluding appendage that renders the wearer inaccessible not only to others but to himself and, more important, to what he denominates as the “divine emanation.” The “portals” of communion to self and “greater than self” are closed. Schuon is working with the occult concept of self-evasion, the urge to hide from the demanding world of spirit, the intimate source of one’s true, indwelling identity. This is a far more interesting idea than the familiar and rather vanilla sociological thesis that we all wear camouflage in our public lives before we “unwind” at home into our “real selves.”

‘I have looked at data,’ Miller writes, ‘From the granular county level to entire countries, and have yet to find examples showing clear and sustained benefits to mask mandates.’ The studies cited by ‘official’ science and pandemic agencies contain ‘transparent flaws in both reasoning and method.’

A mask of the physical sort is always a disguise, a means of obscuring recognition, and in its general acceptation, militating against casual exchanges, mutual intelligibility and normal and open human response. It suggests an air of menace, of the macabre. The omnipresent mask worn by billions of people during the pandemic scare has also had the effect of erasing personality, blocking communication spoken and unspoken, and deforming natural human contact. Their individuality erased or at least seriously degraded, mask-wearers are reduced to unquestioning and all-but indistinguishable foot-soldiers in a vast, shuffling, global horde. Why would they do this? Perhaps Schuon’s reflections partially explain the mask’s eery attraction.

The dilemma is compounded by the fact that the Covid-19 mask is now increasingly regarded, irrespective of the frantic denials of “interested” parties, as having been therapeutically null. Best-selling author Ian Miller’s recent Unmasked: The Global Failure of COVID Mask Mandates thoroughly demolishes the pro-mask argument. “I have looked at data,” Miller writes, “From the granular county level to entire countries, and have yet to find examples showing clear and sustained benefits to mask mandates.” The studies cited by “official” science and pandemic agencies contain “transparent flaws in both reasoning and method.”

Swiss philosopher Frithjof Schuon, author of The Play of Masks, believed that hiding one’s face (his preferred term was “veil”) conceals the individual not only from the rest of humanity but from themselves. This enables an evasion from the person’s inner self, Schuon believed sealing off the possibility of communing with the transcendent. In other words, reducing the human to the level of animals.

Swiss philosopher Frithjof Schuon, author of The Play of Masks, believed that hiding one’s face (his preferred term was “veil”) conceals the individual not only from the rest of humanity but from themselves. This enables an evasion from the person’s inner self, Schuon believed sealing off the possibility of communing with the transcendent. In other words, reducing the human to the level of animals.The great mask wearing experiment, Miller concludes, was a monumental failure as a mitigation measure. For much more on this subject, see this two-part C2C research piece or this recent National Post column by Ontario ICU physician Matt Strauss. Strauss notes that to date there have been only two randomized controlled trials of mask-wearing during Covid-19, the more recent of which studied 340,000 people in 600 villages and found that “cloth masks were of almost no benefit” and surgical masks marginal.

It is decreasingly a matter of opinion and increasingly a matter of plain fact to say the Covid-19 mask has been a gruesome joke from the very beginning. The technical details are significant. For one thing, the weave between threads of commercial masks is at least three times larger than the scale of the average SARS-CoV-2 virion. As Medical Life Sciences News reports, masks do not screen out (or keep in) viral microns, which average 100 nanometers in size; the gap in the weave of all masks, with the partial exception of the medical N-95 and P100 Respirator, is far too large at 300 nanometers or more to repel the coronavirus particle.

For another, despite what the chorus of bought-and-paid-for Internet “fact-checkers” as well as government and med-industry affiliated organizations vociferously clamour, mask wearing in itself is physiologically harmful. The BMJ (aka British Medical Journal) in a technically but carefully worded statement makes clear that the downside of masking outweighs whatever benefits were thought to accrue to the practice. And as Judy Mikovits and Kent Heckenlively show in their painstaking volume The Truth About Masks, prolonged masking poses a danger to actual health. Masks may cause hypoxia and consequent immune deficiency issues through the ingestion of one’s own CO2, and create fungal and bacterial biosafety risks. Similarly, Alberta respirologist Bao Dang recently testified as an expert witness that “having the public wear masks, most of which are often wet, dirty, reused, and incorrectly worn, can lead to health problems and inhaling pollutions and secretions over and over.”

The effects in the psychological dimension are equally critical, reducing a vast and credulous population to wards of the state, timorous, conformist and woefully dehumanized, deprived of agency and spirit. In several definitive studies, Steve Kirsch observes in his Newsletter that masking “is all political theater where everyone is adopting a useless intervention in order to convince themselves that they are being protected.”

Citing Danish and other prestigious academic reviews, Bao Dang concurs: mask mandates have been driven not by valid antidotal and preventative assumptions but by “a social and political aspect…causing mass paranoia and fear and panic.” Many people were constrained to mask up in order to keep their jobs; they, too, suffered the humiliation of depersonalization in a world which obliged them to become travesties of their full humanity.

There is another element at play, no less disheartening: the utter lack of intelligent curiosity, of mind itself, in vast portions of the susceptible mask-wearing public. They are an easy prey to “mass formation psychosis,” as Mattias Desmet, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Ghent, has persuasively argued, and perhaps best symbolized by the commonly seen masked driver alone in his vehicle (a practice that achieves parody when such a vehicle is on an empty country road, parody being surpassed by the California motorcyclist photographed cruising along without a helmet, but with a mask). The fact remains. Ordinary commerce between people has been perverted and maimed.

Perhaps even more toxic, the mask has robbed children of their healthy development as social beings picking up facial cues – smiles, expressions of interest or concern or disapproval, signals of availability, semaphores of meaning – which they then learn to copy. The emulative faculty crucial to mental, cognitive and behavioural growth for children is indispensable, but the mimetic component of normal human relationships has been delayed and possibly permanently inhibited by masking.

The co-inventor of mRNA technology, Robert Malone, has put the matter succinctly and alarmingly: “Measured IQ in the very young has dropped. Fundamental childhood delays are easily measured.” Similarly, the Early Childhood Development Action Network, pointing out that this period normally provides a “critical window of rapid brain development that lays the foundation for health, well-being and productivity throughout life,” is concerned that “children [are] at great risk of not reaching their full potential.” Shakespeare’s schoolboy in As You Like It “with his satchel/And shining morning face” has been robbed.

Faces are readable texts, mobile and evocative, rich with import and context. Masks are not. They are one-dimensional integuments. Absent the dynamics of communion, the perpetually masked stand to lose their defining interiority.

With masking mandates it was as if the psychopath and malignant surgeon in the Castle procedural had left the set and entered the real world, transforming people into their masks, casting them as clones of one another, mutilating their humanity, rendering them unrecognizable, and even worse, often inducing them to love their disfigurement or regard it as normal, domesticating the excrescence. The wearing of masks as a habitual part of one’s deportment leads to a defection from self and constricts the flow of daily transactions with others that serve to make us human.

They also make people look ridiculous, next to impossible to take seriously. We become like histrionic caricatures acting out a public burlesque of genuine selfhood. In short, the mask has gone a considerable way toward scumbling or disfiguring our common humanity.

Unfortunately, we are not like the central characters in a Castle installment, rescued from our nemeses and returning psychologically unimpaired to our daily routines. Of course, many have now shed their masks and are visibly the happier for it, but the harm has been done as real people still need to come to terms with their abasement and still have to “face” mumbling and exploitable multitudes shuffling about in an eldritch farce of their own creation. They – we – are now, in more ways than one, aphasic beings. The collective masking of the human race was an immedicable disaster. While millions will doubtless bounce back, and some already are, it ruined all-too many of us for one another.

Individuality is the casualty of the great charade. Many, perhaps a majority, have come to resemble each other, creatures whose visages are distinguished chiefly by the shape, fit and color of their mask, but essentially wearing one another’s pseudo-faces, as if operated on by Castle’s malevolent surgeon. A mad psychotherapist remarks in a further Castle episode that the mask is the face, fixed and expressionless like the porcelain mask he himself wears on his homicidal forays.

Now in real life the malign legacy, a sort of cutaneous pathology, lingers on as uncounted millions continue wearing their masks into the indefinite future – shuffling downcast across parking lots and into a near-empty Canadian Tire or grocery store, or cowering in a restaurant waiting area just metres from laughing patrons, or, indeed, driving their vehicles all alone. They are emptied of their humanity, like ciphers without substance or detectable histories.

Faces can be signs of inner dispositions, a “datum” explored by Oscar Wilde in The Picture of Dorian Gray in which the tissue of evil overlays the painted face. Goodness, on the other hand, is often evident in a cheerful countenance. Faces are readable texts, mobile and evocative, rich with import and context. Masks are not. They are one-dimensional integuments. Absent the dynamics of communion, the perpetually masked stand to lose their defining interiority. As mythographer Walter Otto wrote, “Masks have no back.”

Regrettably, Castle and Beckett cannot help us. Thanks to the mask, we have been “saved” from nothing but ourselves.

David Solway’s most recent volume of poetry, The Herb Garden, appeared in 2018 with Guernica Editions. His manifesto, Reflections on Music, Poetry & Politics, was released by Shomron Press in 2016. He has produced two CDs of original songs: Blood Guitar and Other Tales (2014) and Partial to Cain (2019) on which he is accompanied by his pianist wife Janice Fiamengo. His latest book is Notes from a Derelict Culture, Black House Publishing, 2019, London.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.