Cultural and political memories are ever-shortening in the West. A poll of 3,000 British teenagers some years back famously found that almost a quarter thought Winston Churchill was a fictional character, while an astounding 58 percent believed Sherlock Holmes really did stalk the streets of Edwardian London.

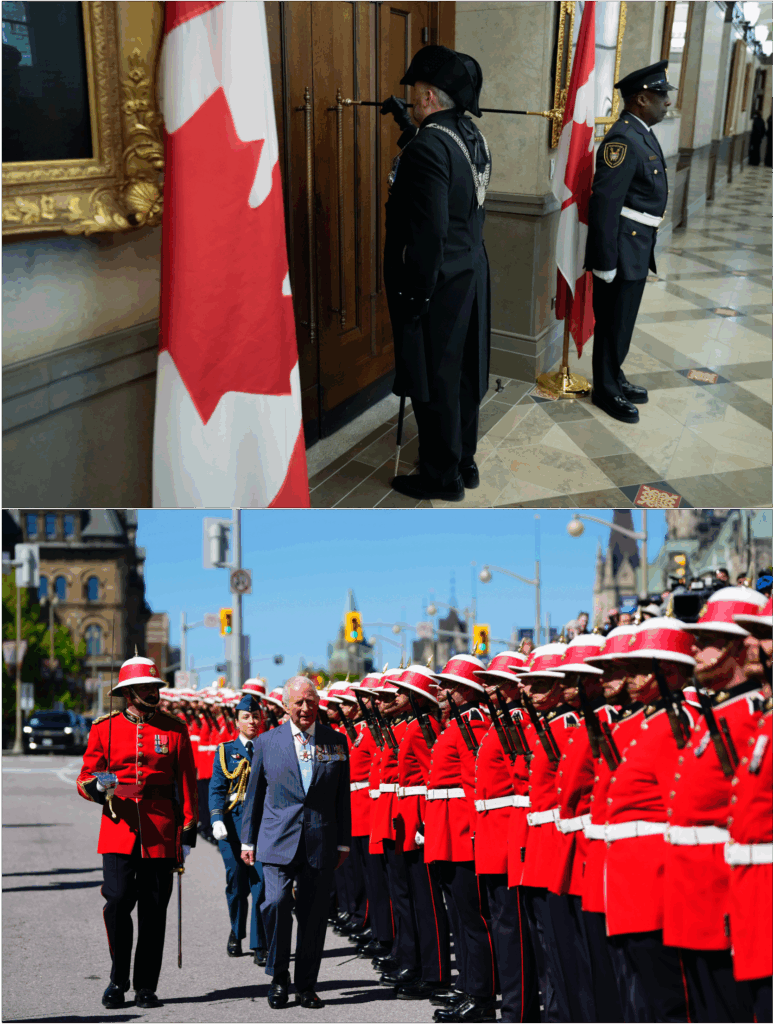

Certainly, King Charles III’s whirlwind visit to Canada last month to deliver the re-elected Liberal government’s Speech from the Throne revealed some of the same cluelessness. In a CBC segment covering the Throne Speech, one young woman said, perplexed: “I mean, I didn’t know there was a King of Canada.” The predominant reaction, however, was a collective shrug. A poll of 1,685 Canadians by the Angus Reid Institute before the event had 83 percent of respondents claiming to be “indifferent”, with only 17 percent admitting “excitement”. Perhaps it is too much to expect mass excitement for a constitutional pantomime, but mass indifference should be a cause for concern.

Yet the physical presence of the King of Canada in Canada was profoundly consequential, coming in the wake of the Liberal Party’s surprise re-election off the back of an antagonistic American government and President Donald Trump’s talk of annexation. The event’s rarity was much remarked upon, this being only the third occasion in Canada’s history that a reigning sovereign delivered the Speech from the Throne in person. Far more important, however, was its geopolitical significance, for despite some recent signs of a rapprochement, the restless superpower to the south seems set to be an increasingly fickle – and perhaps aggressive – counterpart on an ever-more-uncertain global stage. There is accordingly a growing belief that Canada should seek solidarity elsewhere, and reduce its dependence on an unreliable U.S.

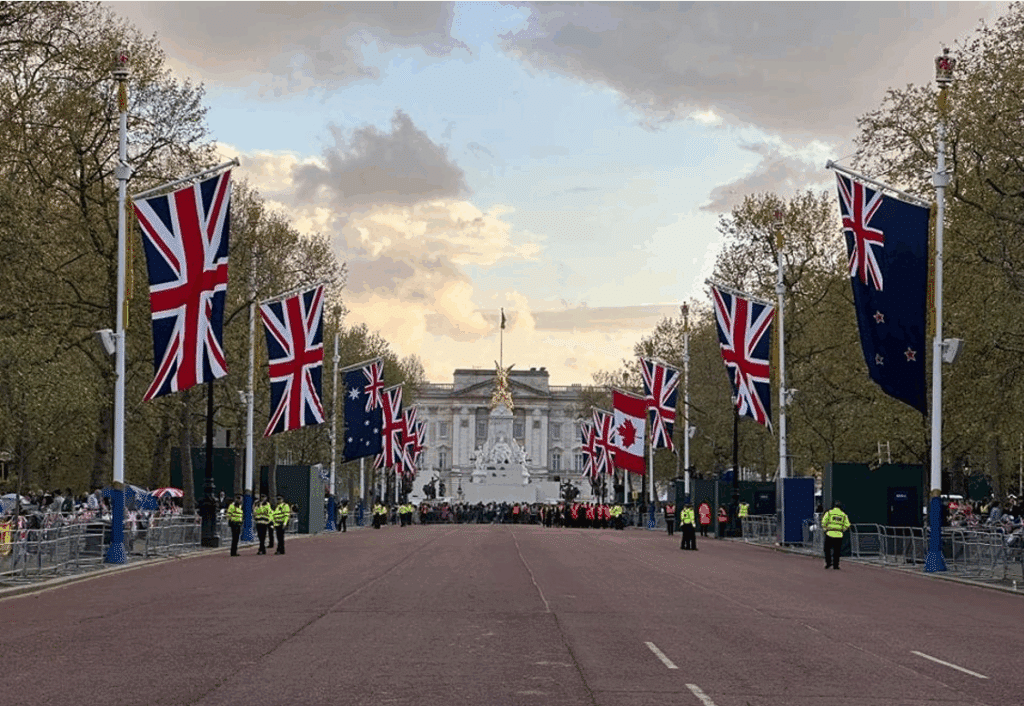

With its ceremony and quaint idiosyncrasies, Charles’s presence gave flesh and blood to the ancient system of government that Canada claims as its own and that, for all the superficial cultural affinity, sharply contrasts this American kingdom with the great, neighbouring American republic. This historic moment offers a unique opportunity to renew the bonds that link the Commonwealth realms – if we are bold enough to grasp it. To counterbalance an erratic United States, Canada should pursue a deeper relationship with Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, building on their common culture, values and a shared heritage embodied in the monarchy – a new alliance embracing collective defence, free movement and free trade.

The Return of the King

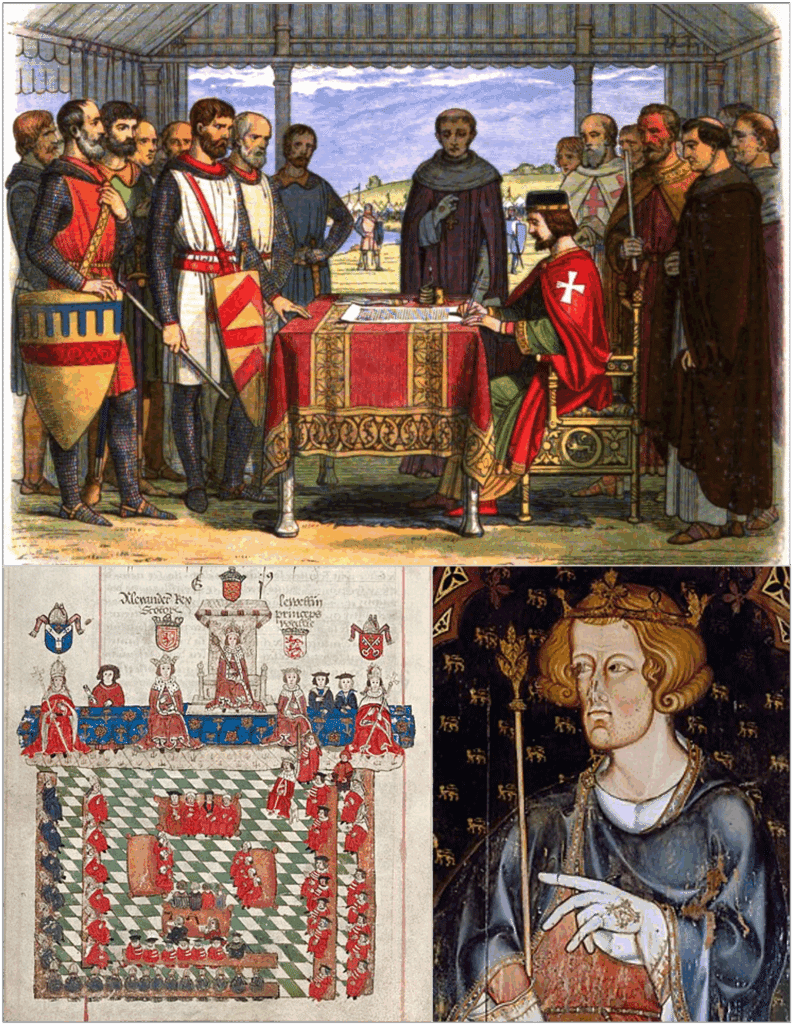

It was quite wonderful – surreal even – to watch re-enacted in the New World a ceremony forged so long ago in the Old. The opening of parliamentary councils by the monarch has its origins in the hazy and chaotic period following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. After imperial authority dissolved and the innumerable tribes coalesced back into kingdoms resembling organized states, the Anglo-Saxon “witan” was an early iteration of this phenomenon – a council of advisors and nobles convened by the monarch to consult on matters of state.

The witan itself remarkably survives today as the Privy Council – from the French privé, brought to England by the Normans in the Conquest of 1066 – while the tradition of the throne speech developed alongside what we know today as Parliament. The term was coined in the 1230s and 1240s in the wake of Magna Carta to describe “parleys” (talks) between the King and large gatherings of his subjects. Such meetings grew to be important consultations between the governor and the governed. A speech would often be delivered setting out the King’s aims and intentions and seeking the parliament’s approval. Particularly for the raising of taxes, the idea that the Crown’s authority was accountable – even if not elected in any modern sense – was a key step in the evolution towards “responsible government”, the Westminster system which Canada inherited.

Astute political operators early on realized the power of a symbiosis of Crown and Parliament. The executive (first King, then Prime Minister) came to manage the burgeoning legislature as a means of stabilizing their authority through the consent of the governed. Indeed, it was the strong kings such as Edward I who regularly called and consulted Parliament, while weak and insecure kings such as Charles I shut them down. While consultative assemblies of nobles and dignitaries were common throughout Medieval Europe, only the Westminster Parliamentary system flourished over time and persists to this day.

The King himself made this point at the beginning of the Throne Speech: ‘The Crown has for so long been a symbol of unity for Canada. It also represents stability and continuity from the past to the present. As it should, it stands proudly as a symbol of Canada today.’

Freedom grows from these sorts of particularities of time and place. Rights are not bestowed by a piece of paper – a Charter or a Declaration – or the whim of some international judge. Far from an outdated piece of theatre, King Charles’s visit to Canada was a physical enactment of the long history that gave us what we have today. We saw, for example, the Usher of the Black Rod ceremonially barred from entering the House of Commons. This ritual represents the occasion in 1642 when Charles I barged his way into the chamber, in breach of privilege, leading to the English civil war, the King’s execution and, eventually, the momentous Bill of Rights of 1689. That is why this ceremony continues to take place across the national and regional legislatures of Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Great Britain.

So the spectacle of Charles III inspecting his troops, as Commander-in-Chief, on the wide streets of a North American city, a clear blue sky overhead, the crack of artillery shattering the peace of the day, and the stirring strains of bagpipes filling the air, was as much an assertion of nationhood as the Constitution itself. Wrapped up in that scene were a thousand years of history, and more. That heritage is the true anchor for the liberties of Canadians.

The King himself made this point at the beginning of the speech: “The Crown has for so long been a symbol of unity for Canada. It also represents stability and continuity from the past to the present. As it should, it stands proudly as a symbol of Canada today.” And that is why Canada can never be just a 51st state.

The United States and Canada are almost antitheses in the European political tradition. On the one hand we have a revolutionary republic, forged in violent upheaval, designed essentially from scratch. On the other, the Westminster system, the eventual product of cumulative incremental change over vast stretches of time. Canada’s basic constitution, shared among the Commonwealth, was sculpted by the experience of generations. It was old before America existed and was venerated even then for being, as the Scottish poet James Thomson put it, the “matchless constitution”.

For all the commonalities of language, law, economy and culture – cemented by proximity and a shared pioneer spirit – Canada’s current rift with the U.S. reveals deeper, older, more philosophical differences.

Is the constitutional monarchy still relevant in modern Canada?

Yes. Canada’s constitutional monarchy, with King Charles III as its Head of State and an elected Parliament representing the people, dates back to medieval England. The powers of the state and the liberties of its citizens are defined not just by a recent written Constitution but by centuries of responsible government, cumulative constitutional conventions and incremental change. It anchors Canada’s freedoms in history, not ideology, and represents stability and continuity from the past to the present.

A Mere Matter of Marching

Lord Palmerston, Britain’s prime minister in the mid-1800s, was well-known for his pragmatic foreign policy. “We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies,” he told the House of Commons in 1848. “Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.” Since its founding, the U.S. has equally vigorously pursued its own national interests, and those have not always coincided with Canada’s. The idea that the U.S. should actually incorporate its northern neighbour – by force if necessary – has a long pedigree.

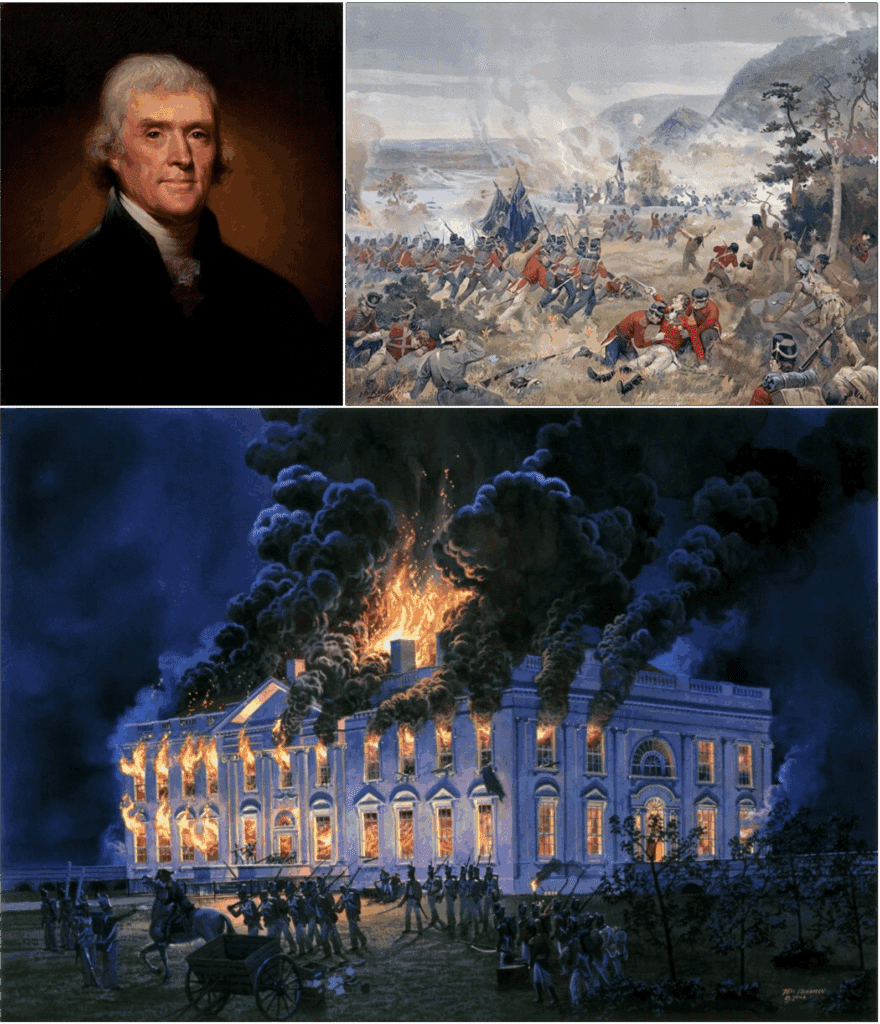

“The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching,” wrote former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson to his friend, the radical journalist William Duane, in August 1812. Keen to exploit a British Empire heavily engaged in fighting Napoleon Bonaparte, President James Madison had engineered the first ever declaration of war made by the U.S. in the hopes of achieving, in Jefferson’s words, “the final expulsion of England from the American continent”. This did not go as planned. Only a few weeks after Jefferson’s letter, Madison had to flee Washington, D.C., as the British army advanced upon the brand-new capital, burning down the newly-built White House.

The belief that the U.S. should dominate the Western Hemisphere endured, however, and was summed up in the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, an idea that continues to be invoked in American foreign policy circles. (As late as the 1930s, America still had explicit plans for a pre-emptive invasion of Canada in the event of a war with the British Empire.) Bound up with the concept of American exceptionalism and its distinct political tradition, U.S. expansionism and hegemony were in tension with the Puritan (i.e., quasi-religious) notion of America as a shining “city upon a hill” that repudiated the backwardness of France’s Ancien régime and other European monarchies.

Since that War of 1812, we have had more than 200 years of economic integration and cultural convergence, even down to everyday facts of life such as the side of the road Canadians drive on. Canada was originally one of the few countries with a mixed system, with a right-handed (Continental) rule in the former New France (now Quebec and Ontario) and a left-handed (Commonwealth) rule in the Maritime provinces and British Columbia. Sold as a measure to attract commerce and tourism, the holdouts harmonized their systems with the U.S. in the 1920s.

Canada has long been happy to accept the economic boons of access to an enormous consuming market next door and, more recently, to an even greater degree than many of its NATO allies, to offload defence responsibilities to the U.S. Hundreds of thousands of Canadians live and work in the U.S., and around 75 percent of Canada’s exports go to the American market, supporting innumerable jobs and fuelling growth.

But these benefits come with a downside. The “longest stretch of undefended border in the world” is a fact, but it is also misleading – as much an expression of economic and geopolitical dependence as of peaceful coexistence. Canada now finds herself deeply enmeshed with a superpower that is increasingly open in asserting its self-interest. Rather than representing a complete U-turn from previous American foreign policy, however, Trump has merely torn away the comforting veil of pretence.

Going back to the Second World War, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “destroyers-for-bases” deal required Great Britain to cede territorial rights in Newfoundland and the Caribbean in exchange for 50 rusted First World War warships – most of which, on arrival, much to the surprise of the British, needed an overhaul before they could be used. The deal, among others, is strikingly similar to Trump’s treatment of Ukraine over mineral rights in exchange for military aid.

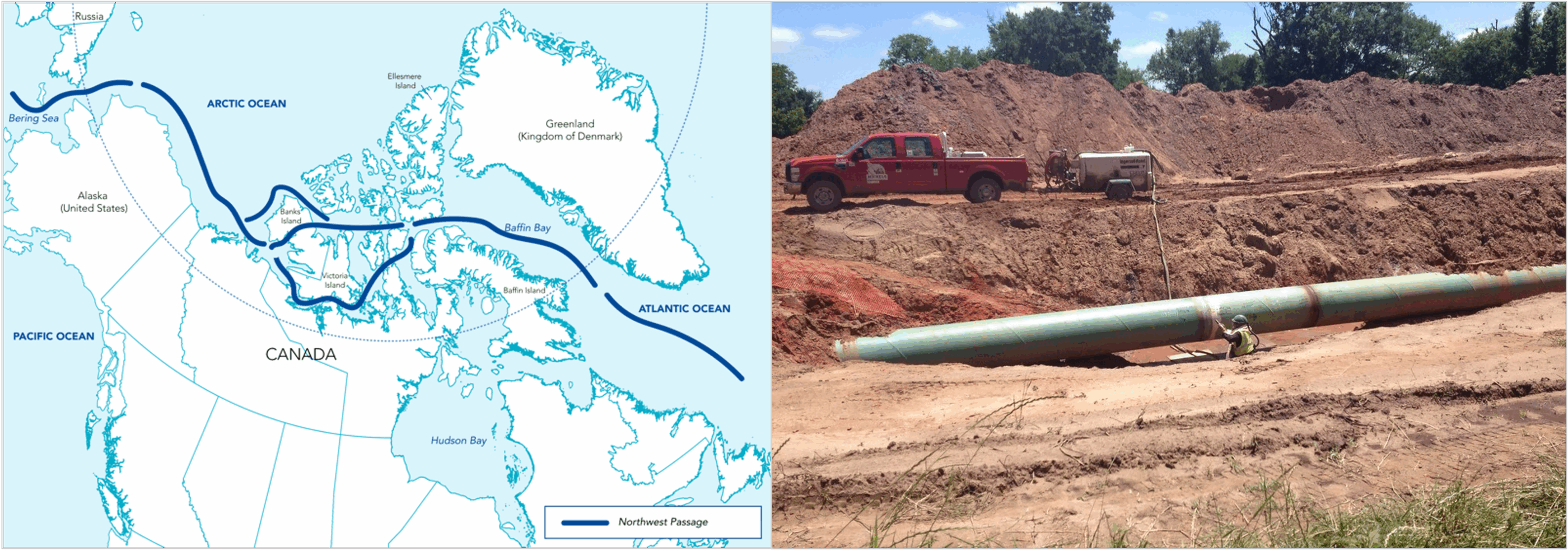

Vicious trade wars and conflicts over sovereignty are also nothing new. Based on concerns of national security, the U.S. has consistently refused to recognize Canadian control of the Northwest Passage – despite that claim being based on standard maritime practices for establishing territorial waters. Equally, the Keystone XL Pipeline project was first cancelled and then relaunched by alternating American administrations, depending on their political affiliation and the project’s perceived benefits or risks to the U.S. – regardless of the loss of billions of dollars of Canadian investment.

There are no four nations on Earth with greater bonds and commonalities than Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom: united by a Crown, kinship and collective sacrifice in war, among others.

“America First” is no mere slogan, it is the dominant international perspective of the U.S. – and, frankly, is a defensible outlook for any country. Where these interests have coincided with Canada’s, it has fostered great collaboration. But the sooner Canadians realize that America is not their “friend” – that it is a nation founded on a distinct philosophical tradition, different than Canada’s – the sooner Canada can pursue a grown-up foreign policy that prioritizes its own autonomy over the fleeting profits of U.S. satellite-hood. And one that faces up to the responsibilities of that independence.

The Inheritors of Westminster

Canada cannot and should not rely on the good graces of a foreign power for its security and prosperity. How then is Canada to find her way forward in an increasingly unstable world?

King Charles’s visit reminds us that even if, as Palmerston put it, nations have no friends, they may yet have family. There are no four nations on Earth with greater bonds and commonalities than Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom: united by a Crown, kinship and collective sacrifice in war, among others. Unlike the U.S., which broke off and chose to tread its own path, these fellow-travellers share an ancient constitutional settlement of liberty, monarchy and responsible government.

Ours is the inheritance of Runnymede and Marston Moor, Gallipoli and Queenston Heights. It is, like an aged and polished piece of furniture, the finely-honed product of countless generations. Our constitutional monarchy is a unique system that has produced unparalleled freedom and order; that has confounded the expectations of progressives, unable to comprehend its pragmatic inconsistency, its organic irregularity.

What is CANZUK and why does it matter?

In an age of cheap global travel and the internet, cultural proximity matters far more than physical proximity. A common way of doing things and a shared historical trajectory give these four countries the potential to form a far deeper and more resilient partnership with one another than was ever possible, bilaterally, with the U.S. Formerly a much more close-knit community, Great Britain bears a heavy burden for abandoning its Commonwealth allies and, in a fit of declinist fatalism, throwing itself towards a European federalist project for which its history and temperament made it ill-suited. The UK’s incremental departure from the European Union following the 2016 Brexit vote should free it to become as motivated as Canada to look, once more, to older allies.

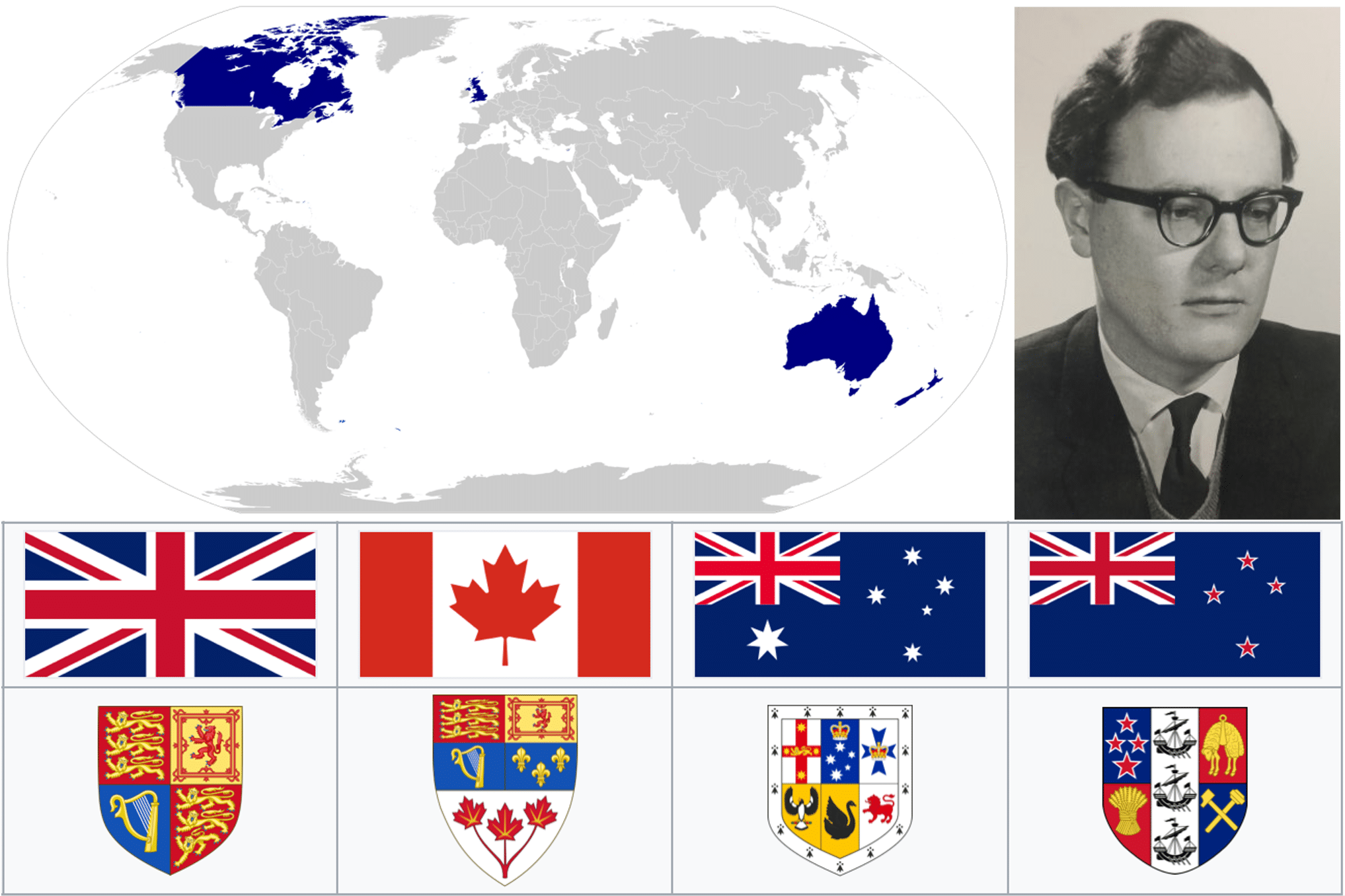

The idea of a close association among Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom – a so-called CANZUK Union – was first proposed in 1967 by William David McIntyre, a New Zealand military and constitutional historian. Support has grown in recent decades across the four countries from major political parties and leaders, particularly in Canada. It has been the Conservative Party of Canada’s official policy for several election cycles and has also been endorsed by public figures including Erin O’Toole, Liberal leadership candidate Frank Baylis, Prime Minister Mark Carney, former Prime Minister of Australia Tony Abbott and Deputy Prime Minister of New Zealand Winston Peters.

The case for such an alliance is compelling. The countries collectively cover nearly 12 percent of the globe’s land area, with a population of over 144 million and a combined 2023 GDP of around US$7.5 trillion (of which Canada generates $2.1 trillion, Australia $1.7 trillion, New Zealand $250 billion and the UK $3.4 trillion) – roughly 7 percent of the global economy. Each of the CANZUK countries relies heavily on the support and cooperation of the U.S. but, collectively, the bloc would rank as the world’s fourth-largest economic power, behind the U.S. (GDP of US$27.7 trillion), the European Union (US$18.5 trillion) and China (US$17.8 trillion).

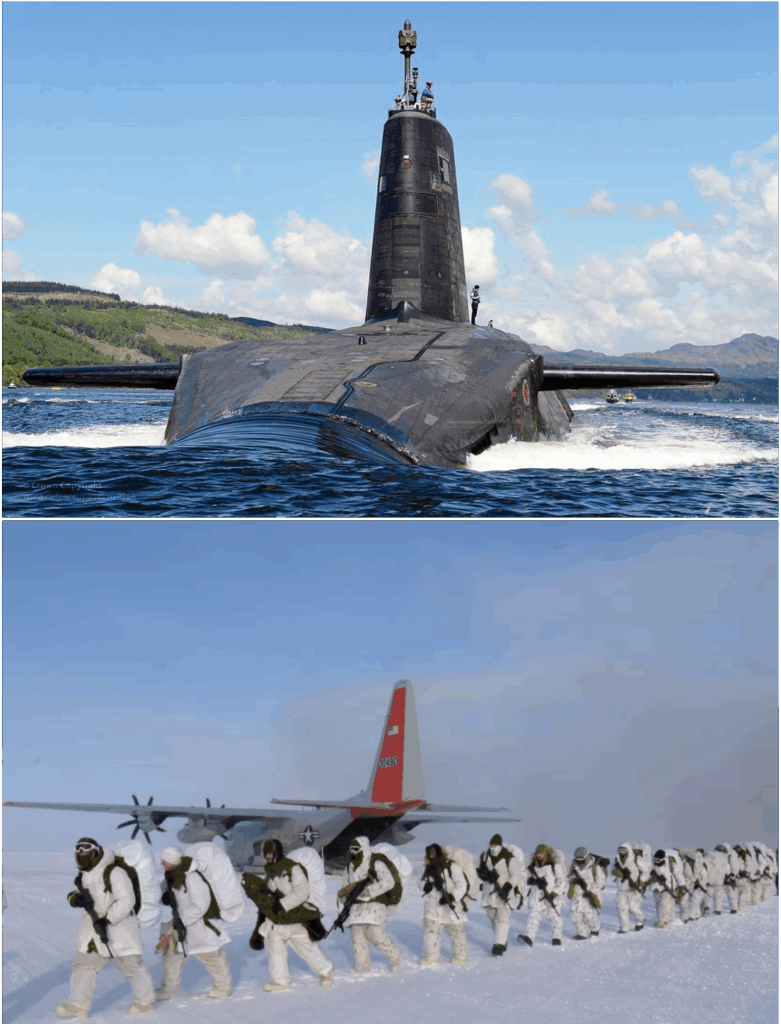

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, CANZUK’s total military spending of about US$142 billion in 2024 (with Canada accounting for $29 billion, Australia $33 billion, New Zealand $2.9 billion and the UK $77 billion) would make it the world’s third-largest global military venture – at least by this financial measure – far outstripping Russia’s pre-war military spending of approximately US$70 billion and behind only the U.S. at US$968 billion and China at US$317 billion. As a bloc, CANZUK could wield considerable political and diplomatic clout on the international stage. And if Canada made good on its promises to ramp up military spending, it could pitch itself as a valuable contributor among the four partners.

Closer military coordination could lessen our collective dependence on the United States. Currently 75 percent of Canadian spending on military hardware goes directly to the U.S. We have outsourced our defence to the extent that we can no longer equip truly independent armed forces. The same is true across the West. Although the European Union has pledged to continue supplying arms to Ukraine to resist the Russian invasion, so few armaments are produced by member-states that the EU relies on purchasing those weapons from the U.S. The tap on this supply could ultimately be turned off by a sufficiently anti-Ukrainian (or anti-EU) American Administration.

Canada has already announced plans to join the ReArm Europe scheme, aimed at reducing reliance on the U.S. A more comprehensive CANZUK realignment would be preferable, however, as it could forge an enduring alliance with benefits extending far beyond merely procuring military hardware, and would not be directly vulnerable to the whims of changing European governments.

The other three nations have every reason to support this. Britain’s submarine-borne Trident nuclear missile system, for example, though masquerading as an “independent nuclear deterrent”, is supplied by the U.S. and enabled by U.S. technology. Despite efforts to replace the aging Tridents with new, British-made equipment, the country’s modest defence budget already creaks under the cost, and a potential partnership with France opens the country up to the whims of another, less constant ally.

As has already been floated at the NATO level, the large costs and immense benefits of Britain’s nuclear capability could feasibly be shared among the CANZUK nations in a formal alliance, based on existing UK assets. This would allow the bloc to pursue genuine operational independence from the U.S. and counterbalance mutual strategic rivals. Canada could more easily rebuff American pressure to march in lockstep under the U.S. defence umbrella, and it might also go some way towards remedying poorly managed Arctic defence, while for Australia and New Zealand, a shared nuclear weapons system could better deter Chinese expansionism in the southwestern Pacific.

But if Canada really wants to assert its sovereignty and cut back its security dependence on the U.S. – as well as selling itself as an integral component to potential CANZUK partners – it must urgently rearm. The second-largest country on Earth cannot expect to be taken seriously if it proposes to defend itself with an army that is currently smaller than the New York City Police Department, that flies ancient fighter planes and has a rusting, mold-infested navy that spends nearly all its time dockside. Nor would accelerated defence spending and a collective, CANZUK security structure be incompatible with continued cooperation with the U.S.; negotiating from a position of new-found strength would instead enable our countries to obtain the most beneficial arrangements possible.

In a recent poll, 94 percent of Canadians expressed their support for a four-nation free trade agreement. Canada could make a compelling, emotive case that reinvigorating the ties that bind the Commonwealth offers hope and security in uncertain times.

Pledging deeper economic ties among this family of nations, as Carney has done, is a welcome step, but our goal should be something far bolder: an alliance aimed, ultimately, at some kind of loose confederation. Unlike the European Union, such an association would not undermine each member state’s sovereignty but enhance it, with integrated trade and decision-making offering greater security against an outside world in flux. And rather than seeking to homogenize populations with distinct cultures and traditions, CANZUK would bring together like-minded nations with a shared history to safeguard their shared heritage and common interests.

Making CANZUK Work

The CANZUK concept is remarkably popular among the populations of each constituent country. In a recent poll, 94 percent of Canadians expressed their support for a four-nation free trade agreement. Canada could make a compelling, emotive case that reinvigorating the ties that bind the Commonwealth – a free association of free peoples – offers hope and security in uncertain times. This would be far more powerful than if such a case were driven by Great Britain, triggering inevitable accusations of imperial nostalgia.

Building quadrilateral free trade agreements would be a crucial first step, possibly in conjunction with formal mutual recognition of professional qualifications and compatible regulations relating to food and health standards. While it would not supplant Canada’s heavy reliance on the U.S. market, of course, streamlined trade among the other Commonwealth nations could ease the path towards disentangling the two North American economies where it makes sense, and open up new markets.

Australia and the UK each are significant importers of crude oil and refined fuels, two of Canada’s biggest exports to the U.S., and recent bilateral increases in exports show that trade access to these markets is logistically feasible at a large scale, although these would really only take off through construction of the Energy East project. Similarly, Canada’s sizable exports of lumber, precious metals and agricultural products would benefit from streamlined and preferential access to a CANZUK market. For sectors more heavily reliant on and integrated into the U.S. economy – such as aerospace, automobiles and pharmaceuticals – the Trump Administration’s steep tariffs provide a strong incentive to drive diversification within an organization of more stable and reliable partners.

Strikingly, while free movement of labour within the EU was deeply divisive in Britain, with up to three-quarters of the population opposing the idea in the run-up to the 2016 Brexit referendum, CANZUK free movement was and is highly popular. Between 58 and 68 percent of Britons like the idea, as do 76 percent of Canadians, 73 percent of Australians and 82 percent of New Zealanders.

A sense of close relatedness as well as social factors such as similar demography and levels of economic development make free movement a genuinely workable objective. Coupled necessarily with robust controls on external immigration into the bloc and a visa-free right to work, this has the potential to spread talent and to offset skills shortages across each country. CANZUK free movement offers us all the benefits of immigration with none of the cultural drawbacks that lie at the root of most resistance to it.

Although Carney as mentioned has signalled his desire to strengthen ties with “reliable allies” (including the other CANZUK nations), he has given every appearance of being a committed progressive globalist. His sudden antagonism towards the U.S. likely has as much and maybe more to do with his personal dislike of Donald Trump and his politics than his desire to defend Canada’s interests.

Yet the CANZUK project is as much about culture and history as about strategic common sense, making it a more naturally conservative one – looking to Canada’s past as inspiration for its future. Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives have signalled their support for CANZUK trade and movement. As Canada’s Official Opposition once again, they might well consider a more full-throated endorsement, in part as a way to defend the country’s “ancient Great British liberties”.

And if the proposal seems appealing but impractical, we already have examples within the Commonwealth on which to draw: the Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement facilitates near-complete free trade and regulatory compatibility between those two countries, and the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement allows unfettered free movement and an indefinite reciprocal right to work. Kick-starting CANZUK could perhaps best be started by negotiating an extension of these agreements to incorporate Canada and Great Britain. There are obstacles, true, but none is insurmountable. Mainly what we lack is driven and ambitious political leadership.

Why should Canada pursue a CANZUK alliance?

While Canada’s economic relationship with the United States remains massive, it’s also increasingly unpredictable. Relations with the U.S. have grown more difficult as it increasingly prioritizes its own interests. Canada needs to diversify its trade and look elsewhere for economic partnerships, treating its relationship with America as transactional, not fraternal.

More than a straight UK-Canada free trade agreement, a CANZUK alliance with the Australia, New Zealand and the UK would deepen ties with countries who share Canada’s history of freedom and rule of law under constitutional monarchy. Combined, the four nations would constitute the world’s third-largest military venture, as measured by defence spending, and its fourth-largest economic power.

What the World Could Someday Become

None of this matters if we don’t understand and appreciate where we came from. To a modern world weaned on American culture and entertainment, the idea of a King and a throne and some dusty, faded documents seems arcane and perhaps oppressive – let alone the long shadows of an old empire. The truth is quite the opposite. When the ceremony we witnessed on Tuesday, May 27 first began to evolve – over 1,200 years ago on a soggy island across the Atlantic – the power of Charlemagne, first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, would have seemed unassailable. The constitution we have had handed down to us has proven itself the most enduring and adaptable ever contrived. Today we need to band together and defend that heritage, not abandon it to fade away in its far-flung outposts around the globe.

Because of the particularities of its own history, the U.S. can never be as reliable a partner as each of the four CANZUK nations – Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK – can be to one another. Individually each country may be supplicants; together, they would be a force to be reckoned with.

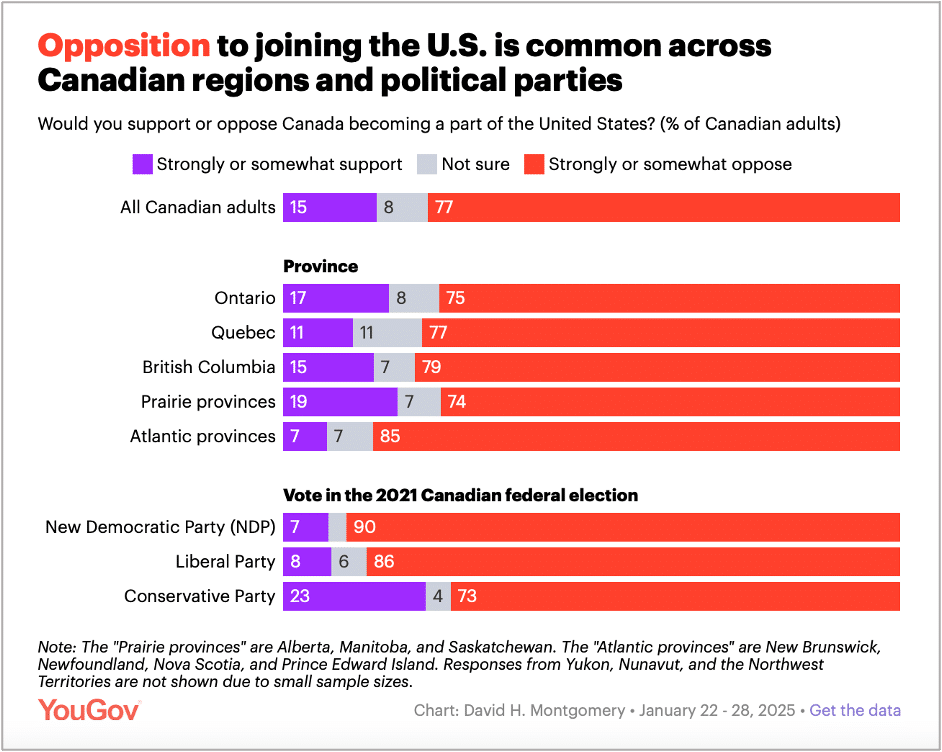

Canadians who value their liberties might convince themselves that life as a U.S. state would be preferable to toiling under Ottawa’s left-wing orthodoxy (among Conservatives, as many as 23 percent feel this way, if polls are to be believed). CANZUK is the answer to that disillusionment. It is a grand vision, one that rejects the self-flagellation of faddish progressive politics, and one that embraces the best of our history with pride as the foundation of future prosperity and collaboration.

Pursuing it effectively would require a brave defence of unpopular ideas; a renewed, outspoken passion for our unglamorous system in a world of shiny, modern democracies of dubious longevity. To move towards it we have to accept that, because of the particularities of its own history, the U.S. can never be as reliable a partner as each of the four CANZUK nations – Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK – can be to one another. Individually each country may be supplicants; together, they would be a force to be reckoned with.

On May 15, 1944, just three weeks before the D-Day landings, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King rose to his feet to address both houses of the British Parliament. “Our first duty,” he said, “is to win the war. But to win the war we must keep the vision of a better future…In the realization of this vision, the Governments and peoples who owe a common allegiance to the Crown may well find the new meaning and significance of the British Commonwealth and Empire. It is for us to make of our association of free British nations a model of what we hope the whole world will some day become.”

Canadians can rediscover that self-belief and, together with the UK, Australia and New Zealand, become a model for the world.

Jamie Weir is an Edinburgh, UK-based evolutionary biologist, with interests in constitutional history. His writing is archived at jamiecweir.substack.com.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.