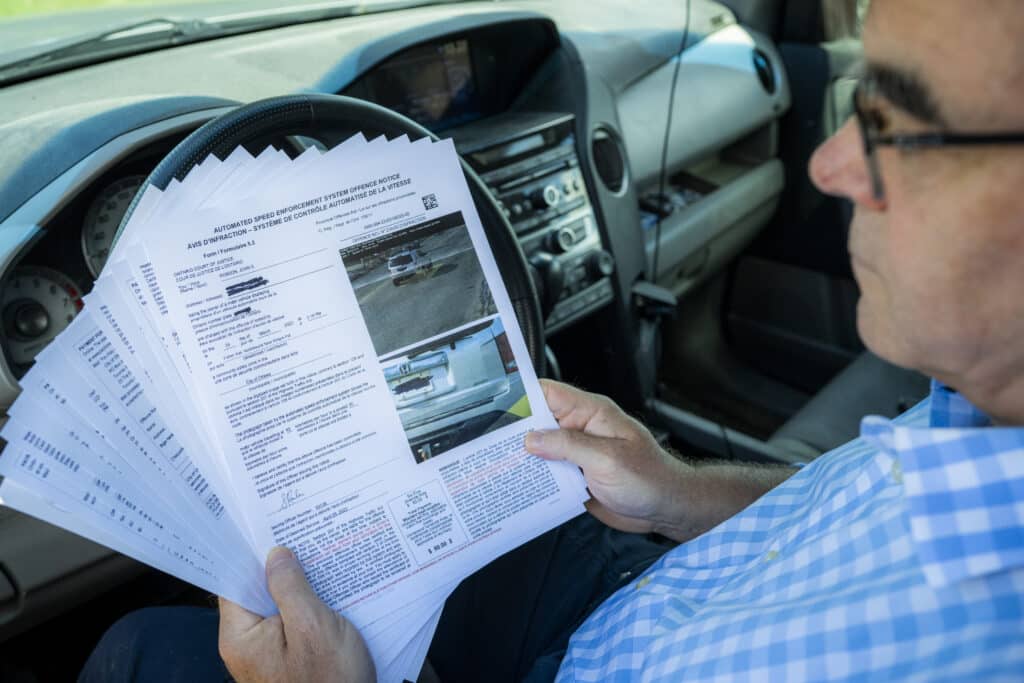

The peasants are revolting. I know. I’m among them. What has me eyeing the Bastille with hostile intent is an “AUTOMATED SPEED ENFORCEMENT SYSTEM OFFENCE NOTICE” that arrived in my mailbox informing me I’d displeased the state by driving 12 km per hour over the speed limit. And would I please hand over my wallet.

I’ve had speeding tickets in the distant past that I certainly deserved. But the four automated speed camera citations for $80 to $95 that showed up over the past year triggered not grudging acceptance but puzzlement and outrage. I resolved the puzzlement by determining that they referred to two intersections in Ottawa mislabelled “Community Safety Zones” where you have to drive unnaturally slowly for three blocks. Then came the outrage.

Since the dawn of the automobile age, the average driver has accepted that dangerous driving deserves some sort of punishment. Millions of Canadians live by this principle daily, avoiding excessive speed and/or accepting their tickets with appropriate shame. But the corollary, as everybody also knows, is you don’t get ticketed for going just slightly over the speed limit, provided you’re not weaving between lanes, smoking a big spliff or playing chicken with pedestrians. By handing out thousands of such tickets every day to Canadian motorists, including the four I received last year plus another more recently, the state is violating the social contract that underpins this country.

Recall that Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms declares that, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” One of the long-accepted principles of “fundamental justice” is living by standing rules that are known to all. So every time a cash-hungry King John (or Mayor Joan) sends Guy of Gisborne (or Robocop) to shake down peasants for driving at what amount to normal speeds, it doesn’t just annoy the target, it violates fundamental justice. Because of this, I’m fighting back. And I invite you to help me slay speed camera Leviathan.

Frown, You’re on Camera

Nearly everybody hates speed cameras and with good, law-abiding reason. The first such monstrosities were unveiled in North America in 1986 on the sun-baked highways of two southern Texas towns, Friendswood and La Marque. While introduced as safety devices, neither lasted very long. “You could say there was a good bit of unhappiness,” Jack Nash, La Marque’s former mayor, told The Los Angeles Times in a retrospective one year later. As the Times noted, La Marque’s automated extortionist quickly earned the town a reputation as a “revenue hungry speed trap”. Many residents simply refused to pay their fines on principle and, after just 110 days, the camera “was run out of La Marque because of community outrage.” Not much has changed since.

Wherever speed cameras have been installed, a similar cycle repeats. Politicians and police chiefs love speed cameras because they allow them to boast of improving safety. Meanwhile the devices deliver a seemingly endless and nearly costless stream of revenue. And it is for this reason that the vast majority of drivers loathe them. In the name of protecting society from speeding deviants, photo radar turns normal drivers into a magical fountain of cash destined for the public coffers.

Supposedly libertarian Alberta was an early Canadian adopter of this habit, installing its first devices in 1987. The province eventually earned the dubious distinction of being home to the most speed cameras in the country: in 2022, for example, 2,400 cameras raked in $171 million in booty, split roughly 60/40 between local municipalities and the province. The Calgary Police Service alone reported issuing 188,000 automated speeding tickets and 27,000 red light violations in 2024, adding a handy $28 million to its budget. The most lucrative photo-radar camera in the province, located at the corner of Baseline Road and 17th Street in Edmonton, generated 52,558 tickets a year (144 per day) and $5.9 million in fines. This sort of efficiency worked freedom-loving Albertans into a frenzy; at one point even NDP leader Rachel Notley decried photo radar as a naked cash grab.

In rural County Wellington in southwestern Ontario, five cameras were installed at various points in January of this year, courtesy of Omnicorp-wannabe Global Traffic Group. After just five days, these one-eyed bandits had written 9,194 ‘penalty orders’, or nearly 2,000 per day.

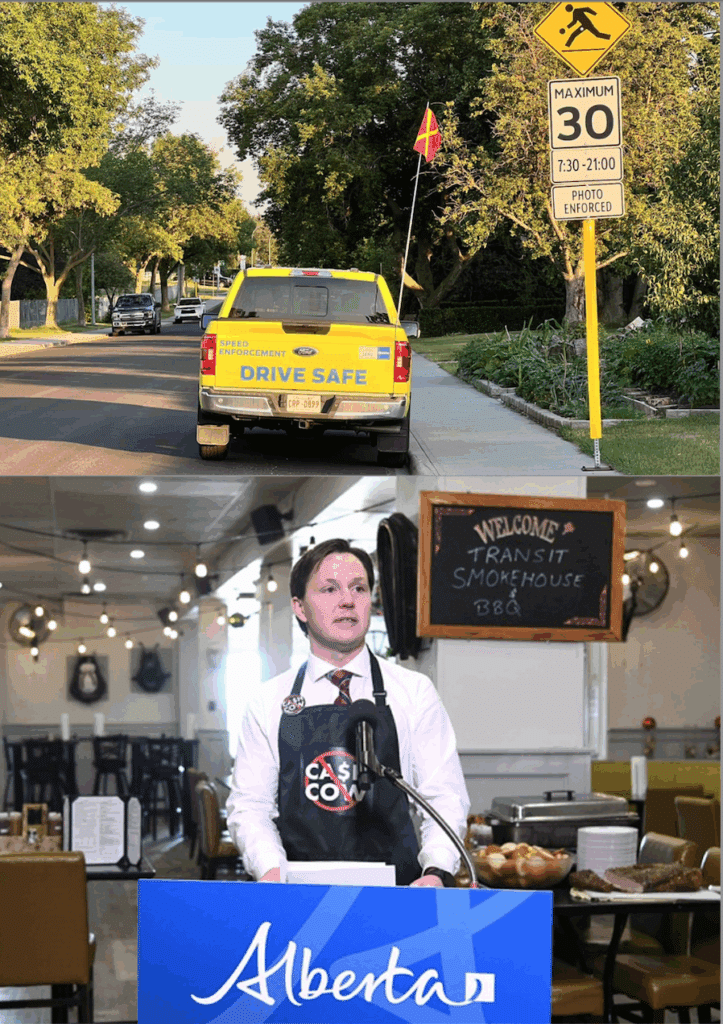

Last December, Alberta transportation minister Devin Dreeshen finally heeded the vox populi and announced he would “kill the photo radar cash cow in Alberta.” New rules that took effect in April 2025 promise to reduce speed camera use in the province by a stunning 70 percent. Numerous municipalities have already sworn off the demons altogether. Amusingly, critics of the crackdown, such as Calgary mayor Jyoti Gondek, claim the province’s planned slashing of photo radar amounts to the UCP government defunding the police. In reality, the Gondek-led council has steadily eroded Calgary’s police service to the point where the city in 2023 had the lowest number of police officers per 100,000 population of any major city in Canada. Using a government’s fiscal incontinence to justify King John’s extortions only compounds the offence.

Bring Me the Head of the Nearest Speed Camera

Photo radar has long tempted a certain brand of bossy-pant politician and repulsed their more populist cousins. In British Columbia, speed cameras were first introduced in 1996 by an NDP government and then killed by the incoming conservative-minded BC Liberals in 2001, only to be revived in 2019 by the new NDP government of Premier John Horgan. The same pattern holds in Ontario as well.

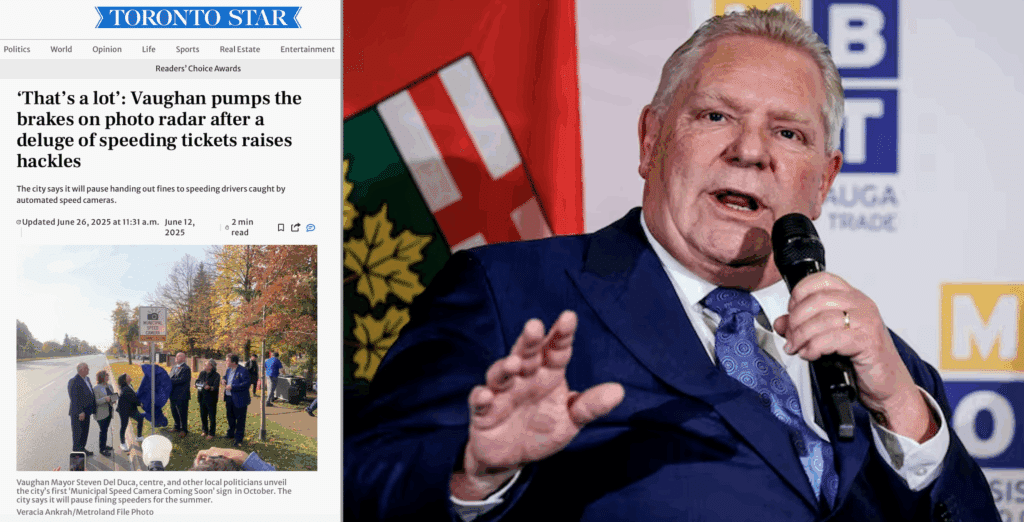

An early brush with photo radar during Bob Rae’s NDP government in 1994 ended after just a few months when Progressive Conservative Mike Harris, who’d campaigned on scrapping the program, took office. Now it’s baaaaack. Photo radar was revived in 2016 by the Kathleen Wynne Liberals and in 2019 the parameters for their use were further loosened by “conservative” Premier Doug Ford. Municipalities have eagerly embraced these new rules, often at the behest of speed camera companies that offer turn-key services at no upfront cost. The result has been a flood of tickets, and public outrage across conurbations big and small.

In rural County Wellington in southwestern Ontario, five cameras were installed at various points in January of this year, courtesy of Omnicorp-wannabe Global Traffic Group. After just five days, these one-eyed bandits had written 9,194 “penalty orders”, or nearly 2,000 per day. Recall that the worst of Alberta’s speed cameras generated a mere 144 tickets daily. According to a report by a County Wellington staffer, an astounding 7 percent of all drivers on those roads during that period got a ticket. “Speed cameras irk some drivers,” a Wellington Advertiser headline deadpanned.

In mid-sized Waterloo Region, a recent confidential report by consultant KPMG forecasts dollar signs rising to the heavens as the municipality ramps up its current Automated Speed Enforcement (ASE) program. “While the region is currently processing approximately 70,000 ASE tickets per year, this number is predicted to hit 875,000 by 2029 as a result of the increase of cameras,” the report states. Given a current population of approximately 700,000, which includes those under 16 years-old and seniors no longer driving, this suggests Waterloo Region expects to hand every local driver more than one ticket annually in four years time. In response to such industrial-scale fleecing, KPMG recommends the region build a new courthouse to handle all the angry residents.

In Toronto, the outrage has gone beyond words. Speed cameras generated 263,000 tickets in the city between January and April, up almost 100,000 over the same period last year. In response, as the Toronto Star reports, the city’s 150 speed cameras have been vandalized 484 times so far this year. One on Parkside Drive has been sawed off its post and smashed six times. Most recently, the perpetrators took the camera’s severed head with them. Similar incidents have been occurring in the UK as authorities simultaneously reduce speed limits and jack up enforcement. How often does anyone try to punch a cop when legitimately caught speeding? The public may not know exactly why it’s wrong, but their gut tells them something is wrong. Very wrong.

Are automated speed cameras legal in Canada?

While speed cameras have been duly authorized by various provincial governments, there is an argument to be made that they violate the time-honoured standing rules of driving and thus conflict with the principles of fundamental justice as outlined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

By the Book

Leaving my Sawzall at home, I went after the wretched things with the Charter instead. As soon as I got the first citation, about a month after the alleged offence, I mailed it back having checked the box requesting a trial.

When my day in court finally arrived, more than a year after the incident, I reminded “Your Worship”, resplendent in a bright green sash, of the old adage that justice delayed is justice denied. That concept dates at least to the original Magna Carta of 1215, whose 40th clause reads, “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.” The same pledge lives on in Section 11 of our sacred Charter: “Any person charged with an offence has the right (a) to be informed without unreasonable delay of the specific offence; (b) to be tried within a reasonable time.” Adding more detail to this right, a crucial Supreme Court decision from 2016 (R v. Jordan) set a presumptive ceiling of 18 months on criminal trials. Canadian courts routinely dismiss charges as serious as sexual assault and fraud because of procedural delays.

Yet I received an immediate, condescending and inaccurate rebuke from the Justice of the Peace (JP), saying Jordan sets a 30-month limit. Actually, that’s for cases in the Superior Court, or cases tried in the provincial court after a preliminary inquiry. The time limit for provincial courts is 18 months. So what’s reasonable for a traffic ticket? After misstating the law, he then convicted me, as they convict everyone. He even told me to cut my defence short so he could shear other waiting sheep. To appeal would require a lawyer and an expensive transcript, another indirect violation of not selling justice. Oh, and in Ontario the fine is increased if you contest a speed camera ticket and lose. For the act of exercising my Constitutional right, my first two $80 fines jumped to $92. They say it’s not intended as a deterrent. But let them reduce the fine if you fight and lose and see what happens.

In addition to bad economics, I got more bad jurisprudence. The JP actually told me I had no Charter rights in his courtroom because life and limb were not threatened, another remarkable piece of bench ignorance. If I refuse to comply with his ruling, eventually cops will be sent to compel me to do so, including, if necessary and in theory, escalating to deadly force. Adding insult to injury, when I sarcastically apologized for taking so much of his precious time with my bothersome Charter rights, he assured me he had “all the time in the world” for me.

Just watch a human police officer with a radar gun for a few moments. I can all-but guarantee he won’t put down his coffee for a driver going 62 km per hour in a 50 km per hour zone.

My next ticket appearance involved a different JP, who also brushed my defence aside. The third told me I couldn’t make a Charter defence without permission from the attorneys general of Canada and Ontario, the very people trying to convict me. It seemed a gruesome breach of due process and separation of powers. But neither this JP nor the prosecutor had any clue about the actual procedure for contacting the appropriate authorities.

After some back and forth, I believe we’ve finally got it figured out and I hope to be able to wave the Charter feebly in court during my next appearance. Stay tuned for a response from the attorneys general, or lack thereof. And another thing: if the third JP was right, then the first two broke the rules by disregarding my Charter rights and proceeding directly to my cases. But who cares? The point was to grab my wallet, not follow due process. Which brings me to why the whole mess is such a serious breach of the social contract first established at Runnymede, England, where the Magna Carta was signed.

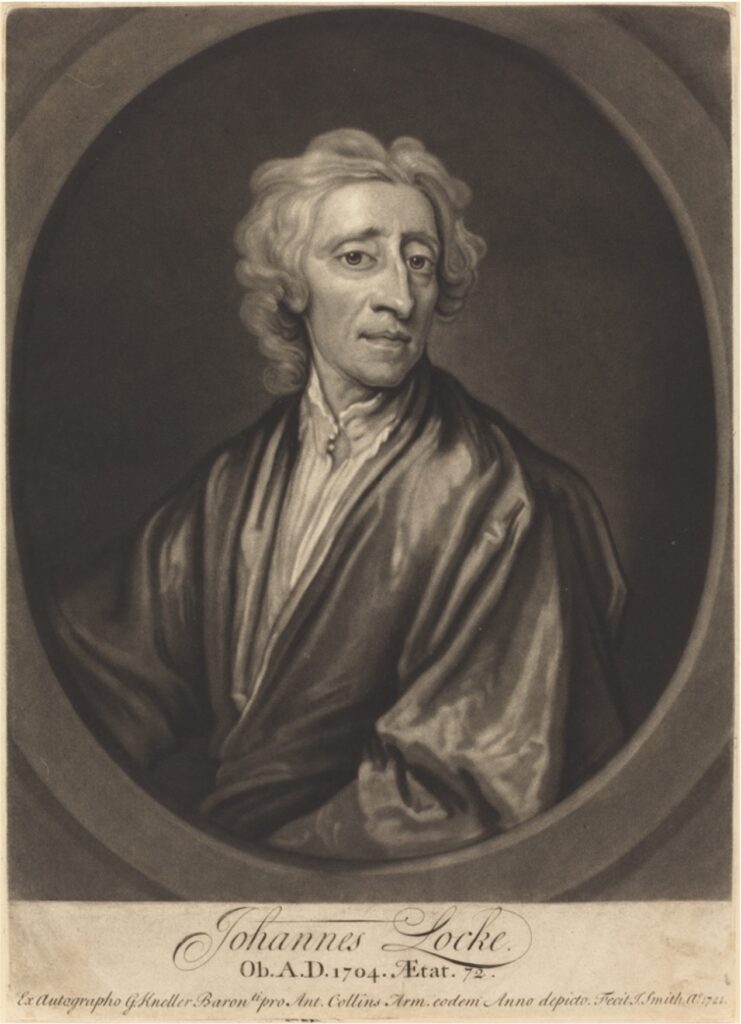

Since the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, it has been a fundamental principle of self-government that laws depend upon the public’s consent. Yet, the author notes, no one ever consented to the dramatic changes brought on by the current proliferation of speed cameras. Shown, a reluctant King John signs the Magna Carta at Runnymede, England.

Since the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, it has been a fundamental principle of self-government that laws depend upon the public’s consent. Yet, the author notes, no one ever consented to the dramatic changes brought on by the current proliferation of speed cameras. Shown, a reluctant King John signs the Magna Carta at Runnymede, England.Locke Cinch

A functioning system of self-government depends on public consent. And you can’t agree to the rules unless you know what they are. This includes not getting a ticket for only slightly exceeding the speed limit. Don’t believe me? Check it for yourself: just watch a human police officer with a radar gun for a few moments. I can all-but guarantee he won’t put down his coffee for a driver going 62 km per hour in a 50 km per hour zone. Some readers, traffic court officials and/or sanctimonious fusspots may say all this doesn’t matter. The law is what it says. Not so. The law is what everybody knows it to be.

As the great British theorist of liberty John Locke wrote in his Second Treatise of Government, “Freedom of men under government is, to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society, and made by the legislative power erected in it; a liberty to follow my own will in all things, where the rule prescribes not; and not to be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, arbitrary will of another man…” This includes the placement of speed cameras in cunningly unexpected spots.

The standing rule about speeding varies according to the situation, of course. If the limit is 30 km per hour in a school zone, 40 km per hour might get you in trouble, especially when kids are arriving or leaving. If it’s 100 km per hour on the highway, 115 km per hour probably won’t cause you any problems in broad daylight, but might if road conditions are dodgy. All drivers know this.

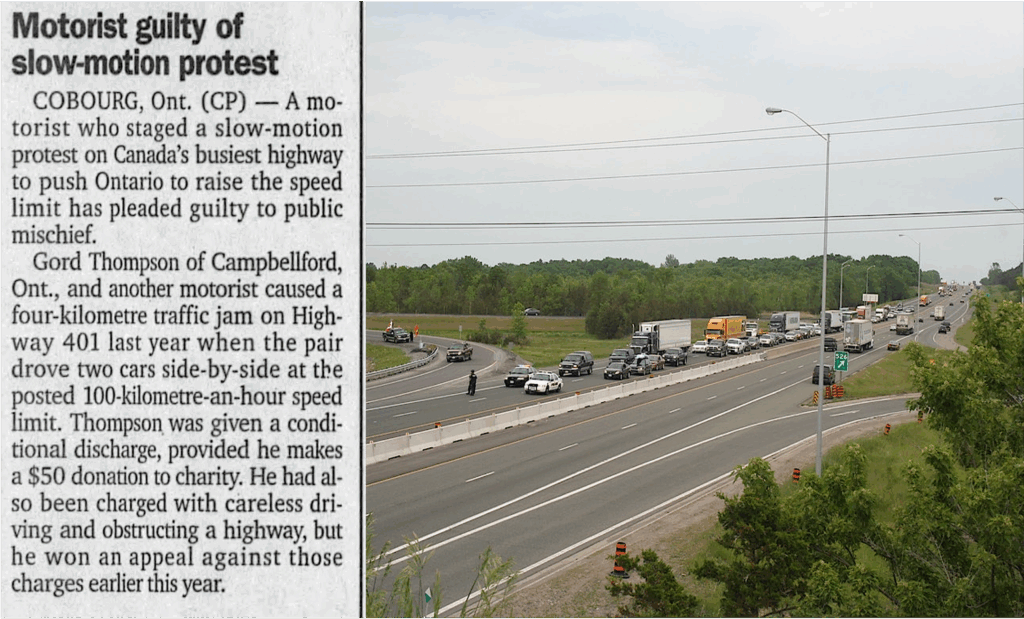

To prove this point, Gord Thompson of Campbellford, Ontario once staged a fascinating, law-abiding protest in 1995. Thompson and a friend drove side-by-side on the busy Highway 401 doing exactly 100 km per hour, what was then the posted speed limit. Predictably, this caused a 4-km-long jam-up behind them, since no one actually drives the speed limit on the 401. But rather than congratulating the pair for their strict adherence to the law, police charged both with obstructing traffic and temporarily suspended their licences. (Thompson’s conviction was later overturned on appeal.)

Subsequent academic research from the University of Toronto established that over 85 percent of all drivers on the 401 were breaking the law at some point by exceeding the posted 100 km per hour limit, which was later raised to 110 km per hour by the Ford government. Conversely, even Ottawa’s speed camera tyrants aren’t ticketing drivers going a measly 2-3 km per hour over the speed limit. So nobody enforces the law literally and we all know it.

As a result, if you’re driving along and suddenly realize you’re 20 km per hour over, you: gasp, brake and sigh with relief that you weren’t pulled over. Or, as was the case with my last real speeding ticket while hurrying to work, you: blush and tell the officer you have no excuse. (For which honesty I got a 10 km per hour discount.) We consent to this system, designed for our safety. We have never consented to photo radar, especially the sneaky kind.

The law as written may not apply: In 1995, Gord Thompson of Campbellford, Ontario and a friend drove side-by-side down Ontario’s busy Highway 401 at exactly the posted speed limit. Far from being congratulated, Thompson was ticketed for obstructing traffic. At right, a clipping from The Sault Star of November 20, 1996 describing Thompson’s stunt. (Source of photo: Bobolink, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

The law as written may not apply: In 1995, Gord Thompson of Campbellford, Ontario and a friend drove side-by-side down Ontario’s busy Highway 401 at exactly the posted speed limit. Far from being congratulated, Thompson was ticketed for obstructing traffic. At right, a clipping from The Sault Star of November 20, 1996 describing Thompson’s stunt. (Source of photo: Bobolink, licensed under CC BY 2.0)Locke’s “standing rule” contained an implicit proviso made explicit a century later by two other great theorists and practitioners of governance, the Americans James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist #62: “It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood…or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow.”

Speed cameras would pose no threat to fundamental justice if the actual posted speed limit was always enforced literally. If a live human officer would always nail you for going 12 km per hour over on a clear day on a busy four-lane street there’d be no injustice in photo radar doing the same thing. Neither would it be a violation of justice if such a massive change in policy were announced, debated, consented to and clearly publicized in advance. A referendum might also be called for. But nothing of the sort has ever occurred. Ontario’s proliferation of speed cameras is occurring piecemeal based on the mostly unpublicized individual decisions of dozens of greedy and unscrupulous municipalities across the province.

Is photo radar about safety or revenue?

While proponents claim photo radar is meant to make roads safer, tickets issued by speed cameras do not assign demerit points and pose no threat to a dangerous driver’s license or insurance. It is thus more accurate to regard speed camera tickets as a new annual driving tax. By 2029, for example, one municipality in Ontario plans to issue more tickets annually than there are local drivers, meaning the average driver can expect to get at least one speed camera ticket per year. Ontario Premier Doug Ford has said he opposes cities using speed cameras as a revenue source.

Peelers for Justice

Getting a speeding ticket used to be a rare event, and cause for self-examination. No longer. Waterloo Region’s plan to hand everyone a ticket or two every year turns this rarity into just another dreary expectation of life – like your monthly hydro bill. Despite the condescending (and inaccurate) “SLOW DOWN! SAVE A LIFE” exclamation on my “Penalty Order”, speed cameras are not really about safety. Since photo radar tickets cannot verify the identity of a driver, no demerit points result and no one – not even the most dangerous, repeat offenders – are ever at risk of losing their driver’s licence or insurance. This process does nothing to remove bad drivers. It’s simply a new annual driving tax.

This new road tax further breaches Canada’s social contract by bringing the entire system of law enforcement into disrepute. The founder of modern policing in the English-speaking world was Sir Robert Peel, who created London’s eponymous “Bobbies” in 1829, and later went on to be prime minister of Great Britain from 1841 to 1846. Peel’s timeless “Nine Principles of Policing” are still posted on countless police bulletin boards and websites across the Commonwealth including, for example, Ontario’s Halton Police Board. Principle #7 reads:

“Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.”

What this means in practice is that when you observe a possible drunk driver or someone going 40 km per hour over the limit, you call it in. As Peel asserted, the public are the police and vice-versa. Plus, we’ve all seen marked and unmarked police cars following the “real” rules. Most recently for me was last month near Smiths Falls, Ontario. When the cop car sped past, my fellow drivers and I didn’t call 911. Rather, we all fell in behind, relying on the unspoken agreement that none of us would get a ticket for going at the same speed as this fine officer.

As I said in my first photo radar trial, it is a near-certainty that every person in the court that day, including the JP and prosecutor, arrived in a car that exceeded the posted speed limit at some point during their journey. Which brings me to Peel’s #3: “To recognize always that to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also the securing of the willing co-operation of the public in the task of securing observance of laws.” No member of the public would ever willingly co-operate in a sneaky revenue grab designed to pull money from their own pockets for an innocuous act that nearly all of their fellow citizens also engage in – some at that very moment.

The fungus-like spread of these trivial but vexing speed cameras thus presents a practical peril. This sort of petty tyranny may turn a populace timid and cowardly or surly and uncooperative. Or perhaps both at the same time, in a kind of passive resistance that renders a society ungovernable through rot rather than revolt.

Regardless of the state of municipal finances, the fiscal imperatives of government are no business of the law. Nor are courts the proper instrument for assisting in the extraction of revenue from the public, a distortion revealed by the hand-in-glove relationship of traffic JPs and prosecutors. Tear off that bright yellow vest that speed cameras cloak themselves in and you’ll reveal a heartless tax collector underneath.

Your Honour, I Object

In his magnificent Democracy in America more than a century and a half ago, Alexis de Tocqueville warned that subjugation to petty tyranny is habit-forming and that, “It is especially dangerous to enslave men in the minor details of life” because, “It does not drive men to resistance, but it crosses them at every turn, till they are led to surrender the exercise of their will.”

The fungus-like spread of these trivial but vexing speed cameras thus presents a practical peril. This sort of petty tyranny may turn a populace timid and cowardly or surly and uncooperative. Or perhaps both at the same time, in a kind of passive resistance that renders a society ungovernable through rot rather than revolt. Some may even be driven to more violent measures, such as the person or persons who keep diligently sawing the head off that Parkside Drive traffic camera in Toronto. And who among us would report them if we saw them in action?

Can you fight a speed camera ticket?

Yes, you can fight a speed camera ticket by requesting a trial. This process allows you to appear in court and present a defence. In Ontario, however, if you contest a speed camera ticket and lose (and everyone loses), the fine is increased. Appealing a conviction is even more expensive, as it may require a lawyer and purchasing a court transcript. Another solution, author John Robson suggests, is for everyone who has received a photo radar ticket to request a court date as a way of increasing the bureaucratic expense of the system and thus diluting its revenue-generating function.

It has now been two years since I began my quest for photo radar justice, or at least to comically illuminate its decay. When justice is delayed, secretive or unaffordable it pulls at the thread of our social fabric. The same holds true when the state is too slow or inept at punishing those guilty of major offences yet strives mightily to punish the innocent in its lust for cash. If my bicycle is stolen or packages vanish from my porch in Ottawa, nothing happens. Even if you provide police with conclusive security footage, as I did with the packages.

Meanwhile the same disinterested state erects elaborate high-tech machinery to squeeze money out of me and my fellow drivers for doing something neither dangerous nor antisocial. Something that is in fact permitted under the unwritten standing rules known to all. Then, when I protest on the grounds of fundamental justice, the courtroom scoffs and spews procedural salad.

I accept that speeding tickets exist for a reason. Past some level, driving fast is inherently a public menace. And if a driver does things an officer recognizes as unsafe, a speeding ticket delivered in person is an objective recognition of more subjective concerns. But an automated ticket to help a city cope with its own budgetary squeeze is an affront to both decency and the rule of law. The fact a photo radar fine may be a minor inconvenience without any loss of demerit points does not mean the practice is not offensive to the Charter.

On that basis I asked those first two judges to dismiss my photo radar fines as a breach of the rule of law; both chose to increase my fines. The third is still trying to figure out how this weirdo with his Charter arguments can be processed and fleeced with minimum effort. We’ll see about the fourth in August. But there’s a silver lining to all this. And it’s not the state’s pockets.

Even now, as speed cameras swarm Ontario, there are signs of Leviathan’s weakness. Public outrage is accelerating across the province. Consider Vaughan, on the outskirts of Toronto, where city council listened to the complaints of its citizenry and recently announced the cessation of speed camera activity within its boundaries. Some seniors told Mayor Steven Del Duca they had stopped going to their weekly bingo games because it had become almost impossible to avoid getting a speeding ticket on one stretch of the route. Is that the point of speed cameras? To keep seniors from bingo?

If you’re with me, I have a very practical suggestion that doesn’t even require a sledgehammer and quick getaway. Let’s test this bunkum about ‘safety cameras’ by contesting every ticket and using every piece of legitimate procedure at our disposal.

It’s equally encouraging that Premier Doug Ford, who perhaps unwittingly unleashed this mayhem in 2019, has been speaking out against it. At a press conference in Wasaga Beach in May, for example, Ford told reporters cities are “using [speed cameras] as their revenue source, and it’s a little unfair.” He added, “They hide them all over the place and if you’re going, you know, 10 kilometres an hour over, you’re getting dinged…People aren’t too happy when they get dinged for 10 kilometres over, five kilometres over. It’s a revenue tool.”

In Ford’s most recent budget, he gave himself the power to set limits on where and how these cameras can be used and, rather cleverly, forbade speed camera firms from benefitting financially from the number of tickets their devices generate. These new rules, the budget document states, are meant to ensure municipalities “focus their traffic cameras on road safety objectives,” rather than just fleecing residents. Revealingly, local authorities are up in arms about the threat to their new source of cash. John Creelman, mayor of the Town of Mono in central Ontario, groused to CityNews that Ford is “parroting all of the negatives about automated speed enforcement, which I prefer to call safety cameras.”

If you’re with me, I have a very practical suggestion that doesn’t even require a sledgehammer and quick getaway. Let’s test this bunkum about “safety cameras” by contesting every ticket and using every piece of legitimate procedure at our disposal. They’ll still get your cash, of course. But it will cost them more in bureaucratic delay and expense than they’ll earn from the fines. If these blasted things really are about enhancing public safety, then the cost of collecting shouldn’t matter. It’s all about slowing down drivers, after all.

But if, on the other hand, it is just a sneaky grab at our wallets, then making the process prohibitively expensive will drive a stake through its dirty heart. If every city and town ends up having to build a brand-new courthouse just to handle the outraged masses of speed camera ticket pleaders, the candle won’t be worth the game. At any rate, I’m fighting back in good polite, law-abiding Canadian fashion. I invite you to join me.

Be a revolting peasant. They deserve it.

John Robson is a journalist, historian and documentary filmmaker based in Ottawa.

Source of main image: Ashley Fraser Photography.