Reconciliation” has been the watchword for Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples for the last 10 years. The federal government grandiosely defines Indigenous Reconciliation as “a renewed, nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationship based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership as the foundation for transformative change.”

So, how’s that going? Not so well, in my opinion. Canada has apologized profusely for Indian Residential Schools, including imaginary unmarked graves and missing children. As prime minister, Justin Trudeau tripled the Indigenous budgetary envelope, his government committing to pay tens of billions of dollars in reparations for alleged deficiencies not just of residential schools but day schools, Indian hospitals, adoption and child welfare services and other policy failings. Public meetings and church services across Canada now open with a “land acknowledgement”, National Hockey League games in Edmonton remind fans that they’re all sitting on “Turtle Island”, towns, roads and historic sites are given native names using a difficult-to-read special alphabet, and Canadians stoically endure harangues from Indigenous radicals pronouncing white people “subhuman”.

And when Prime Minister Mark Carney recently brought in legislation to facilitate construction of major projects such as energy pipelines and port facilities – desperately needed to strengthen Canada’s economy – instead of hailing it as a bold move that could deliver thousands of well-paying new jobs to struggling aboriginal communities, prominent First Nations leaders focused on the perceived affront to their powers and privileges, with some threatening to block Carney’s entire initiative by reviving the “Idle No More” protests and blockades of the 2010s and early 2020. Just this week, nine Ontario First Nations sought a court injunction to bar implementation of any federal or provincial moves to expedite major projects, alleging this would violate a “constitutional obligation” to “advance reconciliation”.

But where is the reconciliation in any of that? Much of the past 10 years seems to have been more about accusation, denunciation and humiliation. And it isn’t getting noticeably better. So if reconciliation isn’t working as hoped, is there some other Big Idea that might bring Canada and Indigenous peoples together for constructive nation-building?

I don’t want to rain on everyone’s parade, but half a century of studying public affairs in general, and Indigenous affairs in particular, has taught me the futility of speculating about the future in deductive terms, which leads to generating current policies by working backward from what we would like to see happen. Deductive thinking is fine when you’re dealing with inanimate objects, like a sculptor planning to carve a statue from a block of marble, but human beings are not objects to be shaped to the artist’s will. Instead, I believe it’s essential to look at the past, to see how the consequences of previous decisions constrain what people choose to do in the future. Once we understand the range of the possible, we might be able to make some incremental progress without running too much risk of unintended and undesired consequences.

The social-science concept of path dependence can furnish a way of organizing our thinking about policy. Every time we make decisions, whether as individuals, organizations or countries, we close off some paths while opening others; the effects can last for centuries. Using the colonies of northern North America in the 1700s as an example, when New France (Quebec) and the Atlantic colonies decided to remain part of the British Empire while resisting invitations to join the rebellious United States, they chose a future of being British in North America. It didn’t become impossible to join the United States at some point in the future, but it was made much less likely. They chose one path forward, which closed off other options.

Path dependence is a recognition of how human beings make decisions and illustrates how the results of past decisions affect the incentives confronting future decision-makers. Perhaps second only to wars and natural catastrophes, past decisions are the biggest influence on current choices. Several past decisions in our history regarding Indigenous people now place severe limits on what Canada might do in the present to shape the future.

Following Great Britain’s acquisition of New France, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (top left) recognized Indigenous “possessory rights” – but authorized only a single buyer, the British Crown itself. At bottom, painting titled Tipis, by George Catlin, circa 1850. (Source of map: U.S. Geological Survey)

Following Great Britain’s acquisition of New France, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (top left) recognized Indigenous “possessory rights” – but authorized only a single buyer, the British Crown itself. At bottom, painting titled Tipis, by George Catlin, circa 1850. (Source of map: U.S. Geological Survey)Royal Proclamation

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued shortly after Great Britain acquired New France, which included what is now the American Midwest. The proclamation is often described as an Indian charter of rights, but that is misleading. It did confirm that the Indians living in New France and west of the Appalachians had certain vaguely defined possessory rights to property, but what it gave with one hand it took back with the other, because it said that Indian property could be surrendered only to the Crown.

Property rights that can be sold only to one buyer are severely limited in value because multiple potential purchasers are prohibited from bidding against each other. Prior to this time, there had been a wide variety of property transfers and surrenders in what is now the United States – some to colonial governors after the conclusion of regional wars, others to local governments and even to individuals through purchases. Now there was only one authorized buyer, able to dictate a “take it or leave it” price: the British Crown.

Throughout the 19th century, Canada followed the policies implicit in the Royal Proclamation: (1) leave intact early arrangements made by the French Crown; (2) leave Indians in remote areas alone so they could continue with the fur trade; and (3) negotiate land-surrender agreements and assign reserves to other Indians.

The Royal Proclamation also made Indians the clear responsibility of the Imperial government. This cut off the experimentation that had been proceeding under local control in the colonies. Some tribes had been defeated in war and had moved further west. Others had taken up land reserves in the colonies. The five “Civilized Tribes” (the Cherokee et al.) had set up a virtual new nation in the Southeast with its own boundaries, legislature and laws, and printing presses. And in most of New France Indians had been left alone to wage war with each other and to engage in the fur trade. Now, there would have to be one centrally approved and imposed model of dealing with the natives. Centralization may have been better for some tribes, but it also meant uniformity and rigidity.

How are Canadian Indigenous relations going after a decade of intense government effort and massive spending?

The policy of Indigenous Reconciliation is defined by Canada’s Liberal government as a renewed relationship based on respect and partnership. In practice, this has involved official apologies, constant land acknowledgements and a tripling of the spending on Indigenous programs under the Justin Trudeau government (2015-2025). But when the Mark Carney government in spring 2025 introduced legislation to fast-track major projects like energy pipelines and seaports – which would create many jobs for Indigenous Canadians – some First Nations leaders immediately threatened to block them, arguing such projects threaten their aboriginal rights.

Confederation

When four colonies in British North America came together in 1867 to form the new Dominion of Canada, it might have been an opportune time to reconsider Indian affairs. The Fathers of Confederation were not interested in doing that, however. They left Indigenous people out of Canada’s founding law and initial Constitution, the British North America Act, except for section 91(24) which, by giving all legislative authority over Indians to the new national Parliament, continued the centralization policy already in effect. The same could be said of the first Indian Act, passed in 1876. It had a new name but continued the provisions of many pre-Confederation Indian laws.

Adhering to the Royal Proclamation’s principles, the new Dominion of Canada negotiated land-surrender treaties with Indian tribes all over Canada except B.C., creating hundreds of mostly small reserves in the process. At top, a Gwichʼin family in Forty Mile City, Yukon Territory; at middle, St’at’imc people of the Lillooet area, B.C.; at bottom, members of the West Moberly band in the Peace River Country, northeast B.C. (Source of middle photo: BC Campus)

Adhering to the Royal Proclamation’s principles, the new Dominion of Canada negotiated land-surrender treaties with Indian tribes all over Canada except B.C., creating hundreds of mostly small reserves in the process. At top, a Gwichʼin family in Forty Mile City, Yukon Territory; at middle, St’at’imc people of the Lillooet area, B.C.; at bottom, members of the West Moberly band in the Peace River Country, northeast B.C. (Source of middle photo: BC Campus)Throughout the 19th century, Canada followed the policies implicit in the Royal Proclamation: (1) leave intact early arrangements made by the French Crown; (2) leave Indians in remote areas alone so they could continue with the fur trade; and (3) negotiate land-surrender agreements and assign reserves to other Indians as their land became wanted for settlement. British Columbia was the outlier; there Canada allowed the provincial government to continue its pre-Confederation policy of disposing of public lands without negotiating surrender agreements. And we are seeing the consequence of that decision today, with overlapping land claims to “unceded” territory amounting to more than 100 percent of B.C.’s total land area, and the very title of lands, resource and property of thousands of British Columbians being brought into doubt.

One important policy that was never written into law but was followed consistently was to break Indian tribes into small groups or bands for the purpose of assigning land reserves. Early Canadian policy makers saw how the American practice of assigning large reserves to whole tribes or groups of tribes led to savage frontier warfare when white settlers started moving into Indian Territory. The Canadian solution was to grant small reserves to sub-tribal bands and then to protect those reserves from white settlement, though sometimes reducing the size of the reserves when a band’s population was in decline.

The Canadian approach prevented frontier warfare but resulted in the creation of hundreds of small Indian communities, now euphemistically called “First Nations”, which lack resources to provide modern services to growing populations. Reserve politics too often becomes a long-running quarrel among familistic factions to divide up what little wealth is available rather than focusing on creating new wealth. The situation is widely deplored, but no one knows how to put the smaller bands back together into larger, more viable units. The incentives for leaders of First Nations to hang onto their local power seem too strong to overcome. Thus, we will continue to have hundreds of small reserves scattered around the country, many in locations with few prospects for success in a modern economy.

Here again, Canada and Canada’s Indigenous peoples are living with the consequences of decisions made long ago, decisions that set them on one path rather than others.

A Path Not Taken: the Trudeau White Paper

In 1969, the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau released a Statement of the Government on Indian Policy, which soon became famous (or, in some circles, infamous) as the Trudeau White Paper. This truly radical document proposed ending all forms of special legal status for Indians, including land reserves and treaties. Canada’s Indigenous people were to have the same status in all respects as all other citizens and, it was assumed, would soon acculturate to mainstream society.

The Trudeau government and the Minister of Indian Affairs at the time, future Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, defended the White Paper at first but then abandoned it in the face of mounting criticism from First Nations leaders. The net result was to further cement in place the special legal status of Canada’s Indians by showing that fundamental change was not politically feasible at that time. Reaction to the White Paper led to the opposite of its intention, namely demands to enhance the special legal status – which is not an unusual result in politics. Here, then, was a path initially taken but soon abandoned, with perhaps worse consequences than if it had never been attempted.

Everything is Constitutionalized

Ratification of the Constitution Act, 1982, was the culmination of Pierre Trudeau’s long campaign to keep Quebec in Confederation by offering explicit constitutional protection to the French language and culture while “patriating” Canada’s overall Constitution to make it entirely controlled by and in Canada. The process also, of course, included creation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Ironically, however, the Act said more about Indian rights than it did about Francophone claims. This happened because Trudeau needed to find allies to pass his cherished project into law, and First Nations had their own claims to make.

Two parts of the Constitution Act are worthy of special note. Section 15(2) offered constitutional protection to affirmative action programs (race-based privileges) that had as their intention “the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups.” Because the whole of Indian Affairs could be construed (in intention if not in effect) as a giant affirmative action program, it now enjoyed constitutional protection. Contrast that with what has happened in the United States, where the Supreme Court has ruled that racial preferences such as those practised in America’s Ivy League universities violate the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law.

![By “recogniz[ing] and affirm[ing]” the “existing treaty and aboriginal rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada”, the Constitution Act, 1982 (shown at left) reopened the previously settled understanding of Canada’s numbered treaties, triggering litigation that continues to this day. At right, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II sign the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, April 17, 1982.](https://c2cjournal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Inset5H-scaled.png) By “recogniz[ing] and affirm[ing]” the “existing treaty and aboriginal rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada,” the Constitution Act, 1982 (shown at left) reopened the previously settled understanding of Canada’s numbered treaties, triggering litigation that continues to this day. At right, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II sign the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, April 17, 1982. (Source of right photo: The Canadian Press/Ron Poling)

By “recogniz[ing] and affirm[ing]” the “existing treaty and aboriginal rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada,” the Constitution Act, 1982 (shown at left) reopened the previously settled understanding of Canada’s numbered treaties, triggering litigation that continues to this day. At right, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II sign the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, April 17, 1982. (Source of right photo: The Canadian Press/Ron Poling)Also, Section 35 “recognized and affirmed” the “existing treaty and aboriginal rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” With one stroke of the pen, Canada’s numbered treaties were now made impossible to change without a Constitutional amendment, while aboriginal rights that had been thought extinguished were brought back into play. The legal community’s understanding had long been that Indigenous people gave up their overall aboriginal rights when they took treaty, receiving specific benefits of land, money and legal privileges in return. The treaties’ plain text certainly states as much, and recorded statements by prominent Indian chiefs at the time demonstrate that this is how Canada’s native peoples also understood the treaties.

The Supreme Court had created a new quasi-property right to be consulted about developments on lands over which First Nations had already surrendered their possessory rights and for which they had been compensated. The Supreme Court has said that the right to be consulted is not a veto, but in practice it is very close to that.

Now, maybe aboriginal rights (whatever they were thought to be) were still in force, depending on how the Constitution Act’s unclear qualifier “existing” was interpreted. All these provisions were deliberately left vague in 1982 so as not to jeopardize the support of any significant political bloc. As such, it became a standing invitation to the courts to fill in the gaps left by the politicians. And they did so with gusto; since 1982, the main features of Indian policy have been driven by court decisions. This was a new path for Canada.

Courts Take Control

Within 25 years, the implications of the 1982 constitutional amendments had become visible for all to see. In the 2004 decision Haida Nation, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that First Nations in B.C. had a right be consulted and accommodated by the government before natural resource projects were undertaken on their “traditional lands”, areas that were both orders of magnitude larger than any reserves and generally undefined. Still, this decision may have made sense in B.C. because Indigenous rights to land in most of the province had never been ceded through treaty.

But then, in the following year’s Mikisew Cree decision, the Supreme Court quickly extended the same principle to Treaty 8 First Nations in Alberta, B.C., the Northwest Territories and Saskatchewan, even though Treaty 8 explicitly provided for surrender of land rights. At that point, governments in Canada gave up contesting the duty to consult and decided to live with that requirement.

Everything constitutionalized: The Supreme Court of Canada’s 2004 Haida Nation decision created the Crown’s legal duty to consult with B.C. First Nations on resource developments in their “traditional” lands; the 2005 Mikisew Cree decision extended this to Treaty 8 First Nations in a vast area, even though Treaty 8 explicitly involved permanent surrender of land rights. Shown at top right, Haida Nation news conference following the 2004 decision; at bottom right, Indian commissioner David Laird explains terms of Treaty 8, Fort Vermilion, Alberta, 1899. (Sources: (top left map) Kungjaada, licensed under CC BY 4.0; (top right photo) CP Photo/Chuck Stoody)

Everything constitutionalized: The Supreme Court of Canada’s 2004 Haida Nation decision created the Crown’s legal duty to consult with B.C. First Nations on resource developments in their “traditional” lands; the 2005 Mikisew Cree decision extended this to Treaty 8 First Nations in a vast area, even though Treaty 8 explicitly involved permanent surrender of land rights. Shown at top right, Haida Nation news conference following the 2004 decision; at bottom right, Indian commissioner David Laird explains terms of Treaty 8, Fort Vermilion, Alberta, 1899. (Sources: (top left map) Kungjaada, licensed under CC BY 4.0; (top right photo) CP Photo/Chuck Stoody)In effect, the Supreme Court had created a new quasi-property right to be consulted about developments on lands over which First Nations had already surrendered their possessory rights and for which they had been compensated. The Supreme Court has said that the right to be consulted is not a veto, but in practice it is very close to that. Canadians have come to learn that opposition to a project expressed through demands for ever-more consultation can derail almost any proposal through seemingly endless delays, because time is money in the real world of resource developments, and the sheer effort required is more than many companies and even provincial governments are willing or able to manage. But no matter how much some politicians don’t like it, they can’t change this new jurisprudence, because the case law created by the Supreme Court’s rulings is based on s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and is therefore effectively part of the Constitution. Path dependency again at work.

The Justin Trudeau government’s 2021 incorporation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) as the law of Canada reinforced the duty to consult and arguably made it even more complicated by overlaying the Canadian law of aboriginal title with a set of international definitions and precepts. UNDRIP, however, in my opinion is only a layer of frosting on the more solid Constitutional cake. It has been made applicable to Canada through federal and provincial statutes that are ordinary legislation and not part of the Constitution. This is not to say UNDRIP is unimportant, but it can be repealed or reinterpreted through the ordinary political process if Canadians decide it is more of a hindrance than a help. But even then, the duty to consult will remain part of constitutional law.

How have Canadian court decisions reshaped Indigenous rights?

Since 1982, Canadian courts have driven major policy changes that have greatly expanded Indigenous rights beyond anything stated in the original numbered treaties, in Canada’s constitution or in its written laws. A key outcome is the so-called “duty to consult”, which stems from a 2004 Supreme Court of Canada decision requiring governments to confer with and accommodate First Nations before resource projects proceed on their “traditional” lands. This principle was later extended even to lands where rights had been explicitly surrendered in past treaties. Though not a formal veto, the duty to consult has derailed many projects through endless delays – and many are now claiming it is a veto. Because the jurisprudence that created it is based on a vague constitutional provision, it cannot be rolled back by ordinary legislation.

The Current Stalemate

A series of decisions over two-and-a half centuries of history in Great Britain and Canada have entrenched the main features of Indigenous policy in the Constitution:

- A focus on the national rather than provincial or local governments;

- The right to special, race-based treatment because of alleged disadvantages;

- The treaty system with its hundreds of First Nations and small Indian reserves;

- Continuance of aboriginal rights even after their supposed extinguishment; and

- Judicial policy making through judicial decision-making beyond the reach of elected politicians to change.

These decisions were not made through ignorance or malevolence but by usually well-meaning politicians and judges, many of whom had devoted much of their lives to public service. But human foresight is always limited. As American baseball catcher and humorist Yogi Berra reputedly said, “It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” Like most other political decisions, these “looked good at the time” but the path chosen led to many unintended and undesired consequences.

Aside from the particular characteristics of each policy decision, perhaps the most important observation to make honestly is that the present-day status quo created by these past policy decisions does not offer a promising environment for major innovation. Many observers talk about repealing the Indian Act, but that is all it shall ever be. Many First Nations are like small rural communities, but under federal rather than provincial jurisdiction. Just as each province needs a Municipalities Act to set the ground rules for the governance of those communities, the federal government needs an Indian Act, or something like it, to provide legal ground rules for First Nations.

There is no shortage of other ideas on the political right: abolish the treaty system and privatize the reserve land base; merge all treaty benefits into an annual cash payment to individuals, something like a guaranteed annual income for Indigenous Canadians; move Indigenous people from remote reserves to locations where they can participate more effectively in the economy. None of these reform proposals has much chance of success. Even if their proponents could convince governments to pass the necessary legislation, itself an unlikely prospect, each of them would probably be struck down by the courts. In any case, they would be met by massive resistance from First Nations and their allies in the academic/activist/media sectors, as happened to Pierre Trudeau’s White Paper.

On the other side of the spectrum, Indigenous radicals also demand repeal of the Indian Act, but with a view to gaining control of all the land in Canada (the “land back” movement), ownership of all natural resources and, at the extreme, even driving all non-Indians out of Canada (apotheosis of the “decolonization” popular in academia and, increasingly, government). None of these proposals has any chance of success, for political as well as constitutional reasons. Forty-one million Canadians – with more every year – are not going to hand over all their land and wealth, maybe even their homes, to 1 million or so First Nations people. Hence, Canada seems stalemated.

Even where the Constitution as now interpreted by judges does not actually prohibit change, politics make it unlikely. Recall how Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government could not even reach an agreement with the Assembly of First Nations to reform Indian schooling. To oversimplify a bit, the AFN wanted a large transfer of money to take over complete control of education but would not accept external standards by which to judge success.

While there are some genuine bright spots – such as the Fort McKay First Nation in the oil sands and the Haisla First Nation in LNG – much recent resource development has been blocked by environmental purists in coalition with, it seems, the minority of First Nations people opposed in principle to modernization.

Nor could Harper’s government allow individual First Nations to introduce fee-simple property rights on a voluntary basis to Indian reserves, despite holding a supportive majority in the Cabinet, the House of Commons, the Senate and public opinion. The “Idle No More” protest movement easily won that battle, so that the necessary legislation which had already been drafted was never even introduced as a bill to be debated.

Why did Canada create a system of small, scattered Indian reserves for its Indigenous People?

Canadian policy-makers in the late 1800s observed that the American practice of assigning large reserves to entire tribes often led to frontier warfare. To prevent this, the Canadian government chose to grant small reserves to sub-tribal bands, a policy structure continued through federal laws like the Indian Act. This approach contrasts sharply with contemporary demands from Indigenous radicals, such as the “land back” movement, which seeks Indigenous control over all land in Canada. The original policy prevented large-scale conflict but resulted in hundreds of small communities that often lack the resources to provide modern services.

Incrementalism and Equity Ownership – A Way Forward?

But even if Canada’s governments and Indigenous people are at a stalemate regarding major change, there is still room for helpful innovations in public policy. One positive sign is the sudden wave of interest, partially prompted by U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff threats, in unshackling Canada’s natural resource industries and giving First Nations meaningful participation including ownership shares. Canada’s First Nations have two major ways to achieve prosperity. Those bands located near cities and large towns can pursue commercial and residential real estate development, as a number are doing – witness, for example, the large development led by the Tsuut’ina (Sarcee) nation along Calgary’s southwest section of its Ring Road.

Those in more remote locations, meanwhile can pursue natural resource-based development such as oil and natural gas, hard rock mining, hydroelectricity, fisheries and tourism, depending on their specific situation. While there are some genuine bright spots – such as the Fort McKay First Nation’s wide-ranging activities in the oil sands in northern Alberta, or the Haisla Nation’s enthusiastic participation in two major West Coast liquefied natural gas developments – much recent resource development has been blocked by environmental purists in coalition with, it seems, the minority of First Nations people opposed in principle to modernization. The at-times violent opposition of such groups to the pipeline feeding natural gas to the LNG facilities upon which the Haisla have staked their future is emblematic of this conundrum. Thus, pipelines have been blocked, mines have not been permitted, and salmon farms have been threatened with shutdown.

Still, this has been an avenue of major success for some First Nations, so more of it should be pursued. Indigenous equity ownership of resource projects does not require constitutional changes, and it will help to solidify First Nations’ support for such projects as well as increase the standard of living of those who participate. With judicious investment, there will undoubtedly be many more First Nations success stories to rival real estate development at Westbank, B.C. and oil sands service industries at Fort McKay.

Loans and loan guarantees are not without risk, however, and sometimes the risks are great. From the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway onward, Canada has had an unenviable record of allowing major projects to blow past their budgetary constraints and construction deadlines, thus leading loans to go unpaid and loan guarantees to be made good by the Canadian taxpayer. For a contemporary example, readers can recall what happened to the Muskrat Falls power development in Labrador.

When offering equity ownership to First Nations, it would be best to concentrate on smaller projects where due diligence is possible during approval and construction, and political interference can be minimized. Despite the inherent risks, resource development with First Nations participation and some governmental financial support is a promising way forward that does not require heroic constitutional changes. It will not revolutionize the situation of First Nations, but it may bring about more success stories in a variety of industries for the Indigenous people scattered around Canada. And having thousands more Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians working productively side-by-side for their mutual gain can become its own grassroots form of reconciliation.

If economic participation and even ownership is the right way forward for many First Nations, it would make sense to diminish First Nations’ current obsession with grievances and reparations. Much of this is derived from Jodi Wilson-Raybould’s “practice directive” when she was Minister of Justice in Justin Trudeau’s government, instructing federal lawyers to prefer negotiation over litigation, i.e., no longer to vigorously defend the Government of Canada’s legal position in court, but essentially to surrender.

In practice, this has led to a proliferation of class action suits seeking large and tax-free settlements for real and imagined past grievances: residential schools, day schools, Indian hospitals, child adoptions, child protection, etc. If you can obtain for hundreds of thousands of followers six-figure settlements by suing the government on their behalf, what does that do to their incentives to improve their own lives through work and education? Wilson-Raybould’s practice directive has no constitutional status and can be repealed by a government that realizes how much damage it is doing.

Finally, there is the reserve system, the bête noire of so many critics. Reserves have many disadvantages, but that is not the fault of First Nations people. Reserves were not their traditional way of life, but were offered to them by Great Britain and Canada in return for giving up their possessory rights to the larger land mass and natural resources of the area that became Canada. Still, First Nations people have lived on reserves for generations and many have become attached to them, as all human beings become attached to their familiar surroundings. Even as there is no Constitutional prospect of abolishing the reserve system, there is thus no practical argument for doing so, either.

The changes I’m proposing may be modest, but now is the right time to consider them. It is widely agreed that, even apart from Trumpian threats, Canada needs policy renovation after a decade of Justinian progressivism.

But there is also no good reason for making reserves artificially attractive places to live. One way this has been done is to make them havens from income and sales taxes for status Indians. This largely came about through a wrong-headed 1983 judicial decision, Nowegijick v. The Queen, interpreting (i.e., expanding) the justifiable immunity from property tax conferred by the Indian Act.

But the courts have also held that exemption from income taxation is a legislated, not a constitutional, right for natives; thus, Parliament could change their special tax status through ordinary legislation. Ending or reducing the tax haven status of reserves could be part of a larger deal to help Indigenous Canadians participate more fully in the economy through a program of loans and loan guarantees. Without those special privileges, they would make their residential decisions the way other Canadians do, balancing locational, economic and sentimental factors.

After 50 years of studying Indigenous relations in Canada, I have settled on incrementalism as the only viable path forward. Incrementalism is not grand and inspiring; it is cautious and practical. It begins by understanding the causes of our current dilemmas. As Hegel said (more or less), the Owl of Minerva takes flight at twilight. Once we understand the reasons for our present situation, we can begin to talk about modest changes that might be constitutionally and politically attainable.

Of course, such changes won’t immediately help all First Nations; but if they enable some to redirect their energy into productive employment and businesses and thereby enhance their own prosperity, they will be worth pursuing. The changes I’m proposing may be modest, but now is the right time to consider them. It is widely agreed that, even apart from Trumpian threats, Canada needs policy renovation after a decade of Justinian progressivism. The federal debt has doubled, the annual deficit is spiralling out of control, our defence effort is underfunded, declining labour productivity has affected our ability to pay for basic public services. Need I go on?

Endless moralizing in a dynamic of grievance from one side and apology/submission from the other plus grotesque overspending all in the name of Indigenous reconciliation isn’t the main cause of Canada’s economic decline, but it is an important part of the picture. It symbolizes the progressive concern with what economist Friedrich Hayek called “the mirage of social justice” to the detriment of other affairs of state. It’s high time for a course correction in many areas, including Indigenous policy.

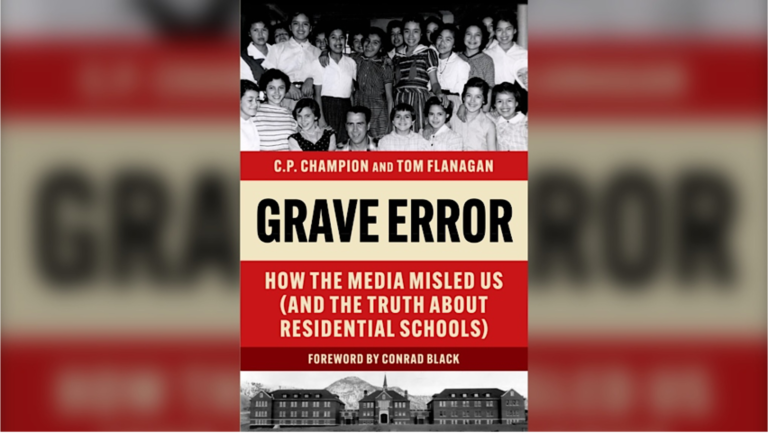

Tom Flanagan is the author of many books on Indigenous history and policy, including (with C.P. Champion) the best-selling Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us and the Truth about Residential Schools.

Source of main image: BC Gov Photos, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.