It is common wisdom among scholars to claim Canada never had a revolution. As the late Donald Smiley wrote in 1980, “Unlike Americans in the eighteenth century…Canadians never experienced the kind of decisive break with their political past which would have impelled them to debate and resolve fundamental political questions.” Similarly, University of British Columbia political scientist Philip Resnick noted in his 2005 book The European Roots of Canadian Identity, “It is a well-known feature of Canadian history that this country, unlike the United States, was not born of revolution.” While Smiley and Resnick were arguably correct about Canada’s past, they were wrong about the future. Canada has experienced a revolution – one going on at this very moment.

Canada’s civil justice system exists so that its citizens can resolve legal disputes through an unbiased and objective set of judicial institutions, procedures and laws. Its proper functioning depends upon the citizenry’s belief that these institutions always act in an impartial and disinterested manner, uninfluenced by governments or special interests and free of political agendas of their own. Today, however, many Canadian judges – from the Supreme Court of Canada on down – are undermining if not upending this country’s once-coherent system of law and justice, and with revolutionary effects if not intent.

In numerous cases involving aboriginal interests over the past several years, Canadian courts have weakened or abandoned what were always considered fundamental precepts of our legal system, often in a manner so damaging that it is impossible not to impute political motivations. These include granting quasi-citizenship rights to residents of foreign countries, creating areas in the country where the Constitution and its protection of individual rights do not apply, enabling nation-to-nation treaties with an undefined and amorphous collection of special pleaders, and recognizing spiritual and subjective claims as superseding provable physical reality.

These shocking outcomes are the consequence of many choices and intermediate decisions by lower-court judges across Canada to favour the interests of Indigenous plaintiffs over the broader interests of Canadian society. And nowhere is this process more obvious and troubling than in the actions of B.C. Supreme Court Justice Barbara Young in the recent case of Cowichan Tribes v. Canada. Young’s judgement threatens to undermine the very concept of private property rights for all Canadians. If that isn’t revolutionary, what is?

The Facts on the Ground

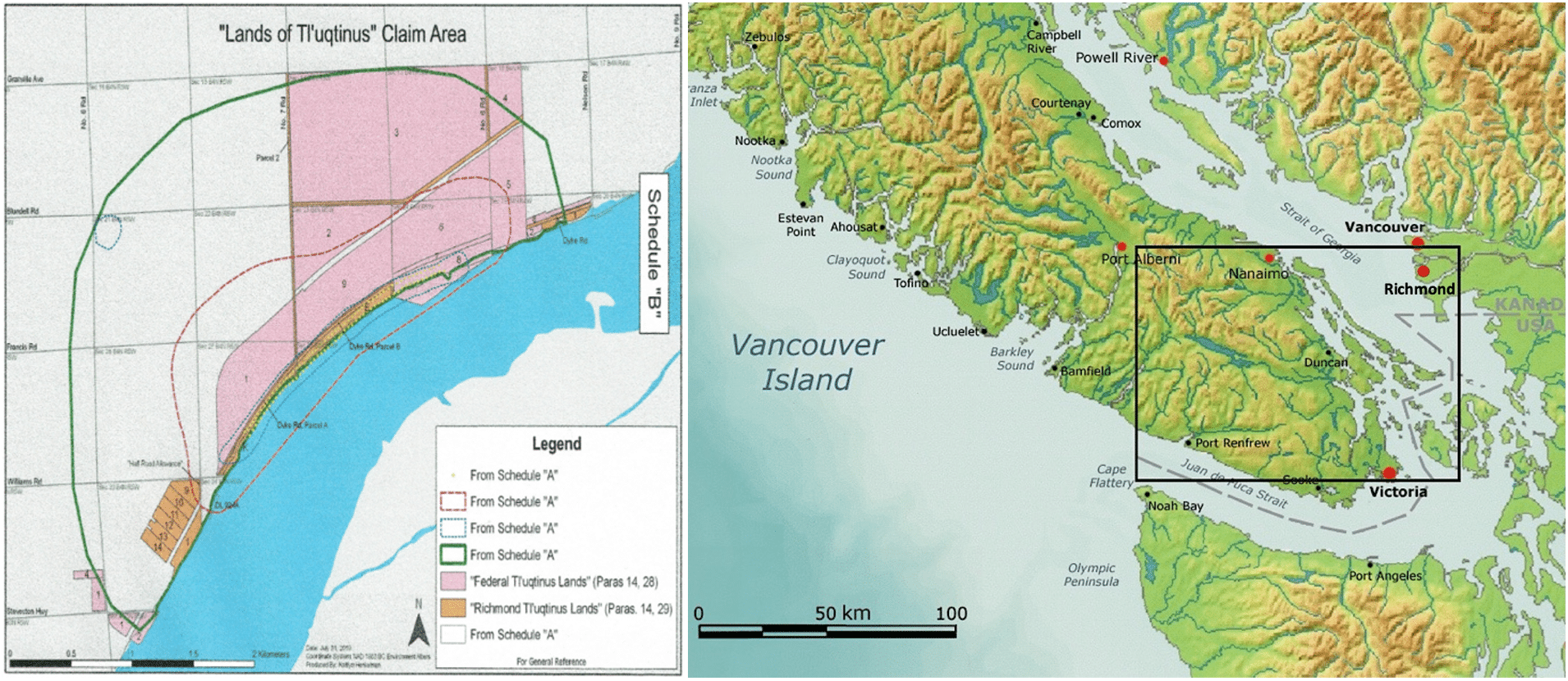

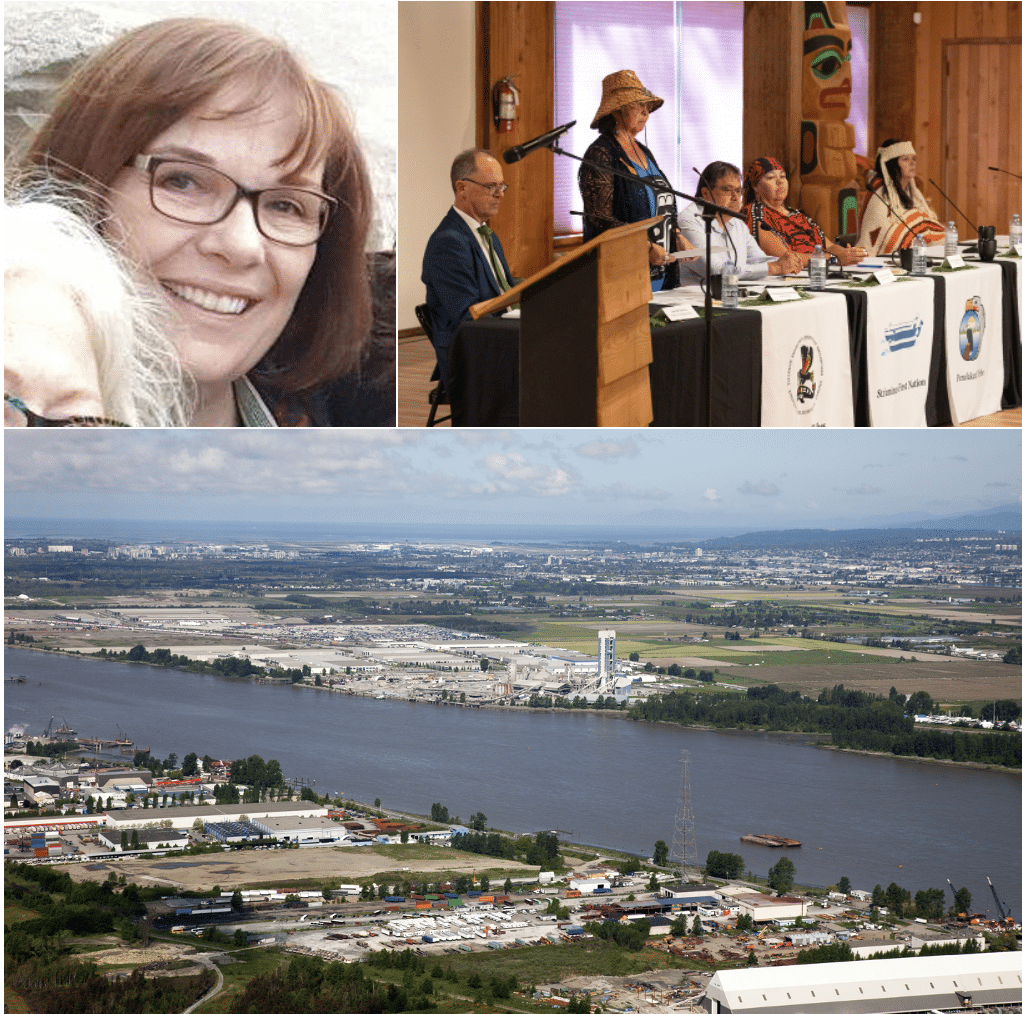

The case involves the claim of the Cowichan tribes of Vancouver Island to a significant piece of riverfront land around Richmond in B.C.’s lower Fraser Valley. The origins of this tale reach back to 1853 when James Douglas, Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, travelled to a Cowichan settlement on the island to arrest a member wanted for murder.

Douglas recorded the details of his trip in his journal, noting that after taking the wanted man into custody, he “informed [the Cowichan] that the whole country was a possession of the British Crown, and that Her Majesty the Queen had given me a special charge, to treat them with justice and humanity and to protect them against the violence of all foreign nations which might attempt to molest them, so long as they remained at peace with the settlements.” As we shall later see, this remark would eventually birth the portentous legal concept known as the “honour of the Crown”.

To understand the full meaning of Douglas’ statement, one needs to know that in 1853 mainland B.C. was not a British colony; it was still under the jurisdiction of the Hudson’s Bay Company. It wasn’t until 1858 that the mainland also became a colony, and Douglas also became its governor. A year after that, Douglas proclaimed that all of B.C. belonged to the Crown and that his new colonial government would identify and set aside reserves wherever there were existing Indian villages, and furthermore that such reserves could never be sold to settlers. (When B.C. joined Confederation in 1871, the federal government assumed responsibility for the reserves.)

![aboriginal_rights_aboriginal_title_Indian_Act_section_35_2 In 1853, Vancouver Island Governor Sir James Douglas (left) arrested an accused murderer who was a member of the Cowichan community. Douglas pledged to “treat [the Cowichan] with justice and humanity and to protect them against the violence of all foreign nations,” a promise would be referenced 172 years later at the B.C. Supreme Court. Shown at right, Cowichan village of Hul’qumi’num (aka Quamichan) on Cowichan River in southern Vancouver Island, B.C., circa 1868.](https://c2cjournal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Inset2-4.png)

In order to record all native inhabitations, the lower Fraser River valley was provisionally surveyed in 1859 by Joseph Trutch, who later became the province’s Lieutenant-Governor. In one of his field books, Trutch noted an “Indian Village”, “Fishing Camp” and “Indian Trail” where the Cowichans now claim they caught salmon and picked berries in summer. The locale never again showed up on any government survey or record. And even if British officials were aware of the temporary camp, it likely wouldn’t have met the requirements of a permanent settlement since it lacked established markers such as permanent buildings, cultivated fields or burial sites.

Nor is there evidence that any Cowichan chief or other representative approached British officials during the colonial survey regarding the existence of their fishing camp. That’s probably because they were living across the Georgia Strait on Vancouver Island. The verifiable historical record additionally suggests the Cowichan were “getting out of the habit” of travelling to the mainland, as they were focussing on trading for Western goods at Fort Victoria and Fort Nanaimo. As a result, the area in question was eventually surveyed into lots and, beginning in 1871, sold in good faith to settlers as fee-simple properties. Among the purchasers was Richard Moody, for whom Port Moody is today named. As the years passed, the area grew into the city of Richmond.

In their lawsuit against Canada, British Columbia, Richmond and others, launched in 2014, the present-day Cowichan tribes allege that the Crown acted dishonourably and unlawfully in selling off their old summer fishing camp. And they want it back.

Aboriginal Title Over Everything

In her August 7, 2025 ruling, Justice Young wholeheartedly adopted the Cowichan’s version of history. Through sheer speculation, she claimed Moody and others used “covert” and “surreptitious” means to knowingly snatch the Cowichan’s lands out from under their noses. In doing so, they breached the Crown’s honour – a recently concocted legal principle that has helped other Indigenous litigants win their cases.

The Cowichan could, presumably, offer to relinquish their aboriginal title for $100 billion, or about $12 million (tax-free) per Cowichan band member. Regardless of the ultimate settlement, this ruling puts all property owners in Canada on notice: aboriginal title can now be retroactively asserted over any disputed piece of land.

Applying this modern concept and other fiduciary obligations to B.C.’s colonial era, Young ruled that the original surveyed fishing camp-area lots were not the Crown’s to sell. Rather, they remained the Cowichan’s property by virtue of their unextinguished aboriginal title. This means that the deeds held by all subsequent owners during the intervening 153 years were and remain invalid because the original Crown patent to the first private owner of each was a nullity, rendering the entire subsequent chain of title to the present day also a nullity.

A witness from the city of Richmond testified that the current value of private and public infrastructure being claimed is about $100 billion. There are currently about 8,000 Cowichan spread out over a handful of reserves on Vancouver Island.

Young’s ruling states that negotiations must take place to “reconcile” the Cowichan’s aboriginal title interests with the interests of the various governments as well as the hapless local property owners who have seen their ownership rights potentially vaporized. The Cowichan could, presumably, offer to relinquish their aboriginal title for $100 billion, or about $12 million (tax-free) per Cowichan band member. Regardless of the ultimate settlement, this ruling puts all property owners in Canada on notice: aboriginal title can now be retroactively asserted over any disputed piece of land, even if it has been legally held and exchanged over a period of centuries by a series of entirely innocent owners.

Such a ruling clearly offends all sense of reason and justice. But how did we get here? A close reading of Young’s statements and actions throughout the trial reveals how a legal revolution can be manufactured. Through her choices regarding the use (and misuse) of language, evidentiary standards, accepted witnesses, historical facts, legal precedent and basic logic, Young’s many small and often innocuous-seeming decisions laid the groundwork for a final, astounding and entirely revolutionary decision.

How could a 2025 B.C. Supreme Court ruling threaten private property in the province and potentially across the country?

The August 7, 2025, B.C. Supreme Court ruling in Cowichan Tribes v. Canada handed aboriginal title to a swath of land in Richmond, B.C. to the Cowichan tribes of Vancouver Island. This land had been surveyed and sold in good faith as fee-simple properties starting in 1871, and so has been privately owned and occupied by others for more than a century and a half. The court decided the land was in fact Cowichan property by virtue of their unextinguished aboriginal title. This ruling means that the deeds held by all subsequent owners over the years were and remain invalid. If this ruling is upheld, it could set a precedent where claims of aboriginal rights can retroactively invalidate legitimate fee-simple property ownership anywhere in Canada.

Step One: Language

In the beginning, as usual, is the word.

The overarching theme of all aboriginal litigation in Canada has been a race-based claim to land rights, money and ultimately power based on section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, which preserves the pre-existing rights of the “aboriginal peoples of Canada”. Litigation is part of the larger pursuit of this political cause – a “nation to nation” relationship with Canada involving, as the Assembly of First Nations states, a focus on “self-determination, lands, resources, culture and identity.”

In accepting and embracing the euphemistic politicized language of the Indigenous cause, the Canadian justice system has steadily eroded its own appearance of judicial impartiality. Instead it appears increasingly aligned with the outlook and goals of aboriginal litigants. Courts, for example, are loath to use the word “Indian” even though it is specifically mentioned in section 35, as well as in the title of the federal Indian Act. As Young stated at the outset of her Cowichan ruling, “I use the term ‘Indian’ only as necessary when quoting from the historical record, legislation and policy, as the word ‘Indian’ has negative connotations and its use can be harmful.”

Following her advice to all parties to “be sensitive”, Young went out of her way to use native language whenever possible, even lamenting that she couldn’t produce court documents in the indecipherable hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ alphabet. When thanking aboriginal witnesses for their “bravery” in speaking to her court, the judge rejoined with “Huychq’u”. This comment was apparently an inside thing between her and the witnesses, as she never bothered to translate it for the benefit of others in the courtroom.

None of this, unfortunately, was even an innovation. In the earlier Restoule v. Canada and Ontario case, for example, trial judge Patricia Hennessy also used biased wordplay. She habitually referred to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, where the treaties at the centre of the case were signed, as “Bawaating”. Hennessey embraced native symbolism as well, allowing an eagle staff, a symbol of Indigenous spirituality and sovereignty, to be erected in her courtroom alongside the flags that denote Crown sovereignty. She also forced the entire court party to participate in aboriginal feasts and sweat-lodge ceremonies and to hear aboriginal teachings on “bimaadiziwin”, or how to lead a good life. At the end of her written judgement – in favour of the native groups, of course – Hennessey thanked all parties in Ojibwe with “Miigwetch. Miigwetch. Miigwetch” – as Young would do with her “Huychq’u”.

Nor did Canada’s highest court find anything the matter with this. In considering the Crown’s appeal of Hennessey’s decision, the Supreme Court of Canada regarded her overt biases to be a laudable feature of her court rather than a flaw: “The trial judge’s sensitive trial process and deep engagement with Indigenous treaty partners undoubtedly made her better situated than an appellate court to decide factual matters.”

What is the legal principle known as the “honour of the Crown”, and how was it applied in the Cowichan Tribes v. Canada case in the B.C. Supreme Court?

“Honour of the Crown” is a legal concept developed and made law by the Supreme Court of Canada in the decades following the Constitution Act, 1982. The court had ruled that once the Crown’s honour has been engaged, Canada’s federal and provincial governments owe a fiduciary duty to the affected Indigenous people and a duty to consult with and accommodate them regarding any contemplated conduct that might reasonably affect them. It follows on the overarching theme of all aboriginal litigation in Canada based on section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, which preserves the pre-existing rights of the “aboriginal peoples of Canada”.

In the Cowichan case, the judge ruled that the honour of the Crown was engaged by an 1853 journal entry from James Douglas, Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, in which he recounted telling the Cowichan that the Queen had charged him to protect them and treat them “with justice and humanity”. In the 2025 B.C. Supreme Court ruling, Justice Barbara Young described it as a “solemn promise” and “sufficient to engage the honour of the Crown,” which proved pivotal to the final decision.

It was traditionally the duty of a trial judge to avoid engaging with the litigating parties except in the courtroom. But in recent aboriginal rights cases, judges have turned this longstanding practice on its head. When courts cast aside disinterested and impartial legal parlance and behaviour in favour of the language and outward practices of a particular cause, they become identified with that cause.

Hearsay – A Revolutionary Weapon

The law in most Western countries regards hearsay – or indirect knowledge – as inadmissible in court because it is inherently unreliable. A witness, for example, can only testify to what they directly observed or experienced, as opposed to something they heard about from someone else. This prohibition has traditionally included so-called “oral history”, which is simply an older form of hearsay (and, technically, is an oxymoron). But this eminently sensible if not critical rule no longer applies in cases involving claims of aboriginal title in Canada. As Young put it, “Altered rules of evidence are permitted to address the inherent evidentiary difficulties in litigating Aboriginal rights cases.”

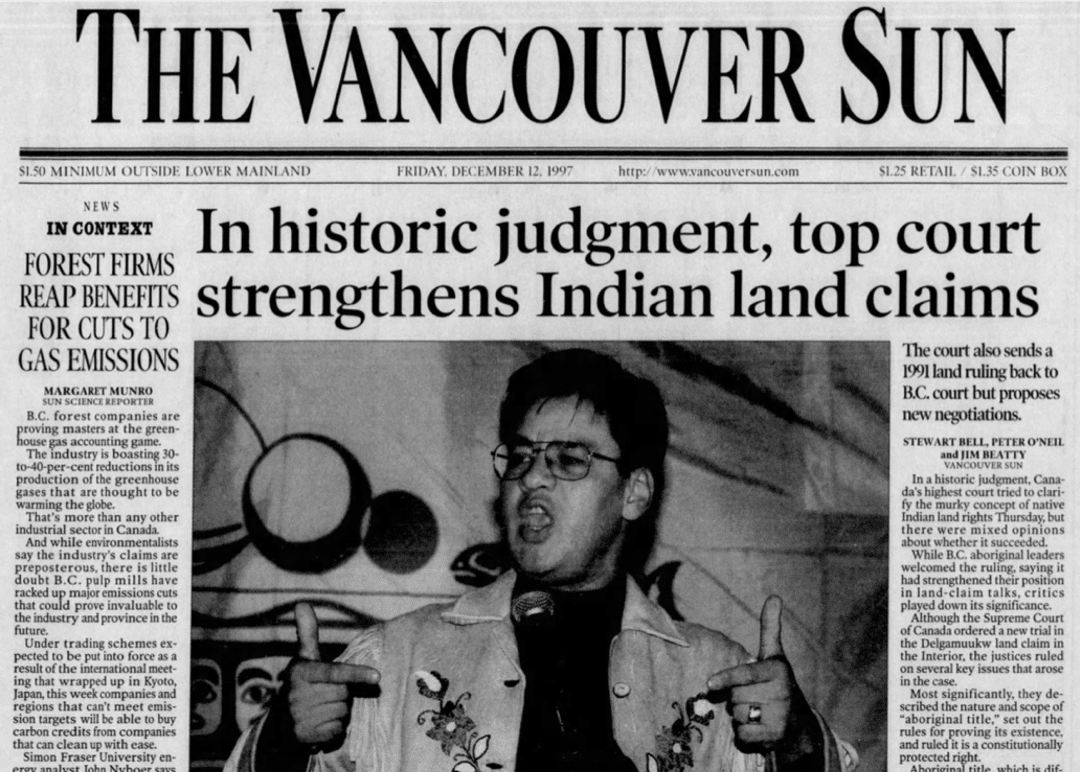

Aboriginal title is itself a latter-day legal invention, first established in the Supreme Court of Canada’s 1997 Delgamuukw v. British Columbia decision. B.C. Chief Justice Allan McEachern had found that aboriginal title did not exist in law. In doing so, McEachern said hearsay evidence regarding where the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en bands, who were now claiming title to nearly 60,000 square kilometres of B.C., had resided in 1846 was inadmissible based on a routine application of centuries-old legal precedent. The Supreme Court reversed McEachern’s carefully reasoned judgment.

In order to affirm that two small native tribes had occupied a given area in the absence of written or physical proof, it was necessary to accept oral history as reliable evidence. In overturning McEachern and centuries of precedent on hearsay evidence, Chief Justice Antonio Lamar was disarmingly frank. “How can the Indians otherwise prove their case?” he asked. Oral history quickly became a leg up for innumerable Indigenous legal claims. B.C. today consists of aboriginal title everywhere that a First Nation can make a convincing oral claim.

In Cowichan, Young did acknowledge oral history’s manifest flaws. Such evidence, she allowed, “includes subjective experience” and “may have elements that are not entirely factual.” She further granted that it “is neither linear nor focused on establishing the objective truth as in the non-Indigenous tradition; the ‘truth’ lying at the heart of oral history and tradition evidence can be elusive.” Young then promptly based much of her decision on the stories she’d heard.

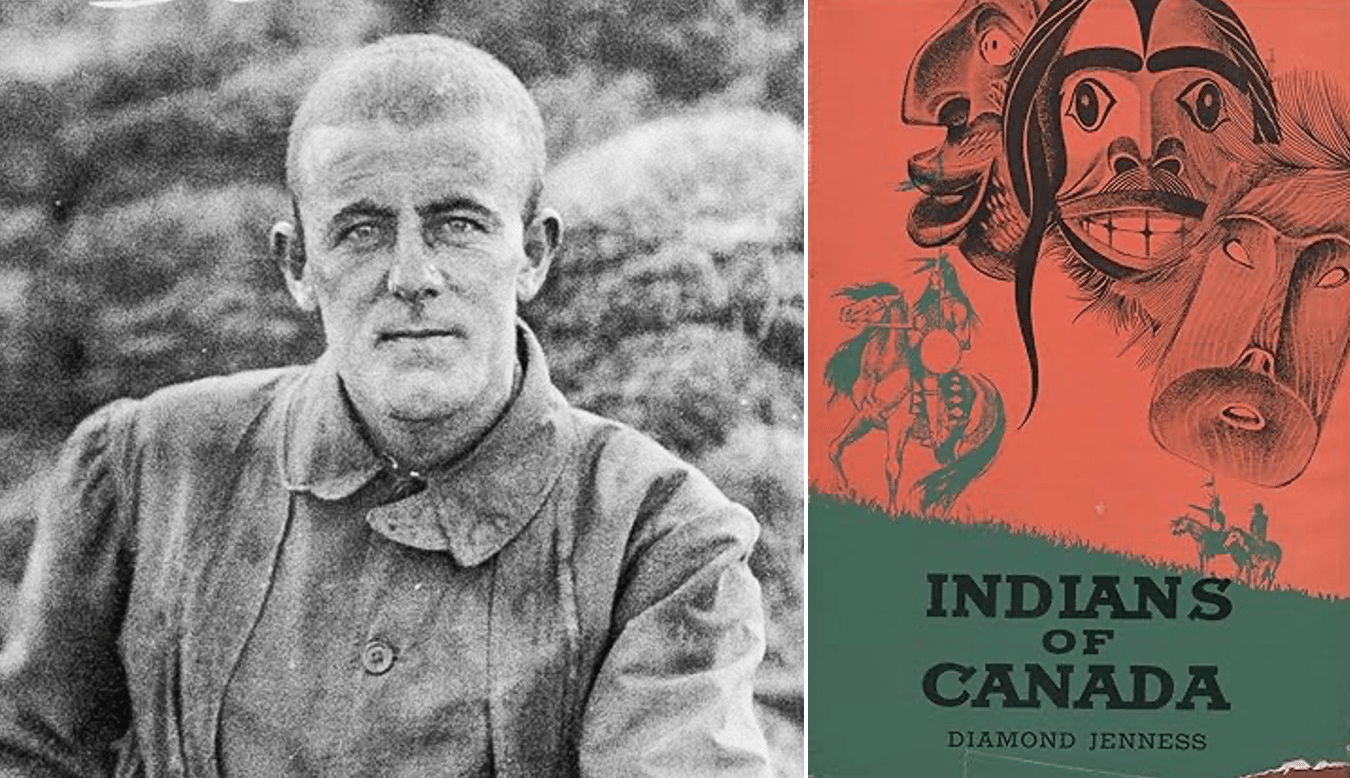

Based on scholarly interviews with Saanich Indians who were born in the 1850s and 1860s – i.e., eyewitnesses to events central to the Cowichan’s case, or at most one generation removed – Jenness wrote in an unfinished academic manuscript that the Cowichan had no fishing rights on the lower Fraser River mainland.

Other judges have even treated Indigenous religious beliefs as reliable legal evidence. In Gitxaala v. British Columbia (Chief Gold Commissioner), for example, the B.C. Supreme Court two years ago ruled that a significant feature of the case turned on the presence of supernatural beings described as “naxnanox”. By purporting to protect the “dens” where the naxnanox resided from the depredations of mining, the court not only accepted mysticism as objective reality but violated the principle of state neutrality regarding religions.

Oral History – Better than Eyewitnesses, Better than Written Records

While Young proved willing to overlook oral history’s myriad flaws, her treatment of written Western-style evidence was decidedly skeptical and hard-nosed. Anthropologist Diamond Jenness, who died in 1969, was once regarded as among Canada’s most learned and compassionate scholars. His The Indians of Canada was first published by the National Museum of Canada in 1932, went through multiple editions and was long regarded as an authoritative resource by universities, governments and others.

Based on scholarly interviews with Saanich Indians who were born in the 1850s and 1860s – i.e., eyewitnesses to events central to the Cowichan’s case, or at most one generation removed – Jenness wrote in an unfinished academic manuscript that the Cowichan had no fishing rights on the lower Fraser River mainland. The oldest of the Cowichan witnesses who provided oral history testimony was born in 1938 – several generations later than Jenness’ interviewees. It would seem reasonable to accord greater weight to recollections of persons born closer in time to the events in question, and decisively greater weight to any true eyewitnesses.

Not Young. Rather, she emphasized picky and technical faults with the memories recorded by Jenness while “understanding generously” the more recent (and thus inherently less reliable) Cowichan witnesses’ recollections of other Cowichan recollections. Wrote Young: “I do not accept Jenness’ opinion about the Cowichan having no right to fish on the Fraser River.”

Young demonstrated her deference to the plaintiffs in numerous other ways. She refused, for example, to let the province argue the position of private property owners in Richmond because the Cowichan had strategically chosen not to sue them. The judge thus ruled residents had no “standing” in her court. And she tossed aside claims that centuries of established property law, including concepts such as estoppel and laches, had any bearing on the case.

When Richmond’s lawyers reasonably argued that a declaration of aboriginal title “will destroy the land titles system…wreak economic havoc and harm every resident in British Columbia,” Young retorted that the suggestion some residents could lose their house and life savings was “not a reasoned analysis on the evidence.” In her opinion, bringing up such concerns “inflames and incites rather than grapples with the evidence and scope of the claim in this case.” Young was willing to entertain the Cowichan’s efforts to usurp the established property rights of Richmond residents but willfully blinded herself and her court to the foreseeable catastrophe such a finding might unleash.

Take Notice

When a court takes what is known as “judicial notice” of something, it is saying that the particular fact is obviously and uncontroversially true. There is no point in wasting a court’s time proving that the sky is blue, for example, via sworn witness testimony, documentation, expert opinion or cross-examination. By such a standard, no court should – and, until recently, no Canadian court ever did – take judicial notice of a contested political or historical matter.

Yet in the Cowichan case, Young accepted numerous highly contestable positions regarding the historical record, without supporting expert testimony or evidence. She used the word “disgraceful” to describe virtually everything the Canadian government did to or for the Indigenous population during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Such sweeping historical generalizations ought to be considered highly inappropriate for an impartial court.

Young is certainly not alone in tipping her hand in this way. The Supreme Court of Canada frequently acts as an omniscient historian, including in the 2024 Reference re An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families decision, which granted quasi-property rights to Indigenous groups in their at-risk children, and 2021’s R. v. Desautel, which handed aboriginals who are U.S. citizens certain Canadian aboriginal rights. Without any properly adduced, admissible evidence before them, Canadian courts frequently upend established historical facts while increasingly using language signalling they accept the ideological premises of the aboriginal litigants.

As part of her rationale for why such defences as conventional property law or statutes of limitation should not bar the Cowichan’s legal action, Young included a litany of lurid, hearsay, unproven and/or out-of-context statements about Indian Residential Schools that focussed on sexual abuse, beatings and other racist or cruel treatment. None of these inflammatory issues had any direct bearing on a case that turned solely on the ownership of a particular piece of property. They did, however, reveal where Young’s sentiments lay.

The $100 Billion Promise

The “honour of the Crown” proved pivotal to Young’s ruling. This concept was developed and made law by the Supreme Court of Canada in the decades after the Constitution Act, 1982. The 2004 Haida Nation decision contained the first specific, focused enunciation. The Supreme Court has since ruled that once the Crown’s honour has been engaged, Canada’s federal and provincial governments then owe, amongst other obligations, a fiduciary duty to the affected Indigenous people and a duty to consult with and accommodate them regarding any contemplated conduct that might reasonably affect them.

Young’s innovation to further expand this breathtakingly broad precedent was to rule that the Crown’s honour was solemnly engaged as soon as Douglas made his 1853 pronouncement to the Cowichan. Recall that Douglas was addressing a local law enforcement matter on Vancouver Island, at a time when mainland B.C. was still Hudson’s Bay Company territory. But, wrote Young, the amorphous Cown honour concept “must be understood generously.” Her ruling positively overflowed with generosity.

To get where she wanted to go, Young elevated Douglas’ obscure journal entry to the level of constitutional promise and his passing reference to the “whole country” as including the entire future province of B.C. The “absence of evidence about what the Cowichan understood the promise to relate to” proved no impediment; Young helpfully filled in the blanks for them:

“That the mainland colony was not yet established is not an impediment to this interpretation. Per Douglas, he informed them that the ‘whole country’ was a possession of the British Crown. Consideration of the Indigenous perspective suggests that there would be no shared understanding about geographical limitations, and the Cowichan’s interests included their interest in their village on the Fraser River. An honourable interpretation of an obligation cannot be a legalistic one that divorces the words from their purpose.”

‘While [Douglas’] promise falls short of a constitutional commitment,’ Judge Young wrote, ‘it bears the hallmarks of one, and as such, in my view it is sufficient to engage the honour of the Crown.’ Such a self-contradictory statement should figure prominently in an appeal – if the defendants have the nerve to pursue such efforts with vigour.

The Supreme Court has ruled that for a Crown assertion to achieve the legitimate status of a constitutional obligation, it must have been given in circumstances characterized by a “measure of solemnity”, and the assertion must have shown a specific intention to create a specific obligation. The 1853 journal entry clearly fails to meet either of these tests. Yet Young described it as a “solemn promise that engaged the honour of the Crown, which is a constitutional principle that requires the Crown to act honourably in its dealings with Indigenous peoples.” She further chose to ignore ample evidence made by colonial officials and supplied by the defendants that contradicted such a position.

Despite her legal bravado, the judge seemed to recognize she was skating on thin constitutional ice. “While the promise falls short of a constitutional commitment,” she wrote, “it bears the hallmarks of one, and as such, in my view it is sufficient to engage the honour of the Crown.” [Emphasis added] Such a self-contradictory statement should figure prominently in an appeal – if the defendants have the nerve to pursue such efforts with vigour, and if the appeals court happens not to be in a constitutionally expansive mood when it rules.

Judges Make Poor Historians

Part of Young’s rationale in elevating Douglas’ 1853 comment to constitutional commitment was that it was intended “to induce the Cowichan, who were a strong military force at the time, to remain peaceful.” Besides a vague assertion of unspecified “tensions” between the Crown and the Cowichan, no evidence was provided that they were threatening war or civil disturbance against the British colony. Douglas’ journal entry instead indicates he was using the privilege of trading at British forts to induce the tribe to hand over the wanted man. “I also told them that being satisfied with their conduct at the present conference, peace was restored, and they might resume trade with Fort Victoria,” he wrote.

The only evidence before the court regarding threats of violence was expert evidence describing the Cowichans’ penchant for war, including their cruel and deadly attacks against the Musqueam, Tsawwassen and other Coast Salish tribes. This, the court heard, frequently involved mass murder, beheadings, kidnappings and enslavement. It was this sort of behaviour that prompted Douglas to arrest one of their members.

The concept of honour as Canadian courts have developed it only burdens one side of the courtroom. Young’s ruling holds B.C.’s 19th century colonial founders to the highest and most exacting present-day moral and legal standards. By contrast, she excuses and explains away substantial and genuinely atrocious behaviour by the Cowichan, arguing that 2025 standards of behaviour should not be applied to their ancestors. “It would not be in the spirit of reconciliation to hold an Indigenous Nation’s conduct centuries ago to retroactive standards of international or Canadian law,” her ruling deadpans. This in a case that is built entirely around the retroactive application of current law and behaviour.

Young went to great pains to criticize B.C.’s colonial founders for allegedly dishonourable conduct which, using modern parlance, was the equivalent of “white collar” misconduct. And yet she gave the colonial powers no credit for the imposition of the British rule of law that outlawed slavery, kidnapping, torture, beheadings and murder and otherwise brought relative peace and order to all the Coast Salish tribes.

By awarding judgement to the Cowichan, Young essentially rewarded them for using violence to further their own aims – conduct far worse than the administrative nature of the alleged colonial malfeasance she found had occurred. Whatever the real story behind the Richmond lands, no Indigenous person was ever beheaded or enslaved on the orders of Douglas, Moody or Trutch.

Why is “oral history” now admissible as evidence in Canadian aboriginal title cases?

The admissibility of “oral history” in Canadian aboriginal title cases was established by the Supreme Court of Canada’s 1997 decision in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia. The court overturned a lower court ruling that had rejected hearsay evidence; the Chief Justice at the time asked, “How can the Indians otherwise prove their case?” (Courts are now loath to use the word “Indian” even though it is specifically mentioned in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, as well as in the title of the federal Indian Act.) Oral history, simply an older form of hearsay, is now routinely accepted as evidence. In the B.C. Supreme Court case Cowichan Tribes v. Canada, Justice Barbara Young acknowledged that oral history “includes subjective experience,” “may have elements that are not entirely factual,” and that its truth can be “elusive.” But she said, “Altered rules of evidence are permitted to address the inherent evidentiary difficulties in litigating Aboriginal rights cases.”

The Reconciliation Rachet Effect

The aforementioned Haida Nation decision held that the Crown honour principle was necessary to best achieve “the reconciliation of the pre-existence of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.” Here the court used the term “reconciliation” in the legally discrete sense of the word. It was meant to represent the legal meshing of the pre-contact and section 35-protected traditional rights of the affected aboriginal band, with the legal sovereignty rights asserted by the Crown, in the smoothest and least-disruptive way possible. At this point, reconciliation held legal and constitutional meaning. It was not a social or political goal.

Since then Canadian governments, aided by enthusiastic courts, have converted the narrow, case-specific, legal doctrine of Haida Nation-style reconciliation into the idea of “aboriginal cause reconciliation” representing the broadest possible effort of political and social nation-making. An effort that Young described as infused with the “spirit” of reconciliation. A “reconciliation” that is increasingly being waged like revolution.

If Young’s ruling is upheld on appeal, the concept that unextinguished aboriginal title invalidates centuries of legitimate fee-simple property ownership would cast all private property held anywhere in Canada in doubt.

The former Liberal government of Justin Trudeau led the way on this, as evidenced by its Directive on Civil Litigation Involving Indigenous Peoples, which was meant to advance an aspirational, political form of reconciliation by disabling the Government of Canada’s defences in aboriginal litigation. Under the Directive, which remains in force under the Mark Carney government, the federal government’s relations with aboriginal Canadians must be based on “the recognition and implementation of Indigenous rights” with the government becoming an agent in “advancing Indigenous self-determination and self-governance” and “fostering strong, healthy, and sustainable Indigenous nations.” (In 2021 Trudeau’s government even declared September 30 to be Canada’s official National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.)

This new biased, “social justice” thinking is everywhere in the court system. In the Quebec case R. v. Montour, for example, Justice Sophie Bourque stayed guilty verdicts against two Mohawks convicted of smuggling 23 tractor-trailer loads of bulk tobacco into Canada and thus avoiding payment of customs duty, on the grounds that they had been exercising their right to trade tobacco granted by their aboriginal “legal system”. Such blatantly illegal behaviour is now supposedly protected by section 35. Bourque thus broke with Haida Nation-style reconciliation in favour of aboriginal cause reconciliation. As she wrote, “Reconciliation aims to address past injustices, acknowledge historic wrongs, and work towards a more respectful and equitable relationship between the Crown and Indigenous people.”

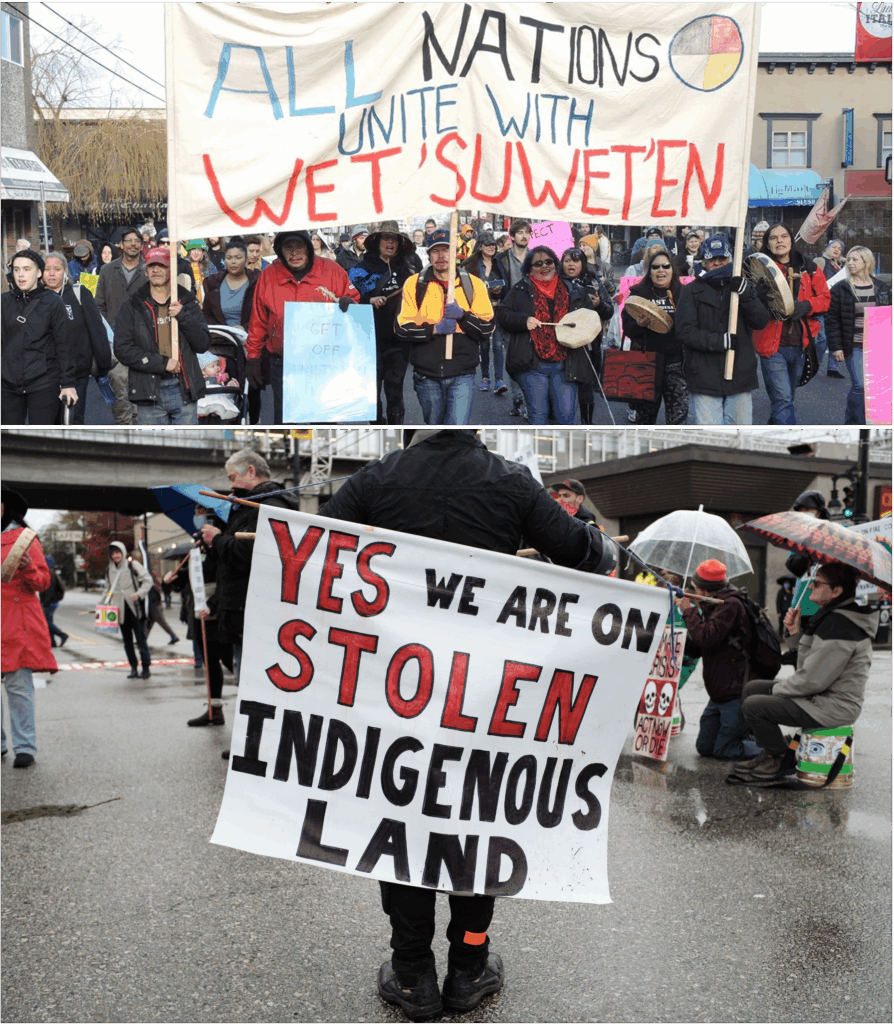

The rachet effect of reconciliation is easily visible in the Cowichan ruling as well. The destruction of existing property rights is meant to “advance” the aboriginal political cause, regardless of the effect it may have on property owners, provincial finances, Canada’s international reputation, the justice system’s stability and reputation – or anything else. But this is no mistake; it is purposeful. It is fundamental to the radical Indigenous “Land Back” movement, for example. It is not a bug, but a feature of the revolution being waged under the noses of Canadians.

If Young’s ruling is upheld on appeal, the concept that unextinguished aboriginal title invalidates centuries of legitimate fee-simple property ownership would cast all private property held anywhere in Canada in doubt. Young stated blandly that private ownership over the disputed Richmond properties is “valid until such a time as a court may determine otherwise or until the conflicting interests are otherwise resolved through negotiation.” How that might be resolved is “not a matter for this court to address”, she said. Like all good revolutionaries, Canadian courts today are mainly interested in throwing bombs. The consequences don’t concern them.

Peter Best is a retired lawyer living in Sudbury, Ontario. He is the author of the 2020 book There Is No Difference: An Argument for the Abolition of the Indian Reserve System and Special Race-based Laws and Entitlements for Canada’s Indians, and a contributor to The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should Be Cherished – Not Cancelled.

Source of main image: Canva.