I like to get to class early so I can get some work done when it’s still quiet on campus. But when I arrived more than an hour ahead of my 9:00 am class in Political Ideologies at the University of Calgary in late March 2023, I found I wasn’t alone.

Standing in front of my classroom were a dozen or so students intent on preventing me from getting inside. As none of them was actually enrolled in my class, I quickly realized this was the business end of a much-promoted “student strike” to protest rising tuition fees. As the strikers milled about the door with determined looks on their faces, a security guard arrived and told them they couldn’t physically block anyone from entering the classroom. This allowed a handful of students, including me, to squeeze past the protesters and take our seats.

Eventually the strikers decided to enter the room as well, at which point they began chanting and banging drums. One had a portable speaker and blasted rock music. When the professor finally arrived, he brought with him a few administrators who went around informing the student attendees that class was cancelled. Given the racket, the prof left a few minutes later; the strikers then paraded around triumphantly, having made good on their threat to shut down my class.

With the “strike” affecting one of the two classes I had for the day, I decided to take the day off from studying and skip my other class. Making use of this spare time, I asked some of the strikers to explain the point of their efforts. In that conversation and subsequent ones with other protesters, I found them rather confused about who they were targeting and what exactly they wanted. Some said the provincial government was to blame for cutting university funding. Others pointed fingers at the school administrators who were directly responsible for the recent tuition hikes. Some said both were at fault. At a conceptual and strategic level, the protest seemed a mess.

Conceptually, if universities are being starved of funds by the province, then you can’t really blame the school administration. As a non-profit institution, it relies on provincial grants and tuition fees for most of its revenue. If the government cuts its funding, tuition fees will have to rise in order to maintain a constant level of service. On the other hand, if the university was being wasteful or was raising tuition simply to pad its budget, then the province might be justified in cutting back to impose some financial discipline.

Things were no clearer from a strategic perspective. By spreading their protests across two different opponents, the protesters were weakening their focus and ensuring neither group faced the maximum pressure. Instead, university leadership could point to government as the “real” culprit, while the province could do the same in reverse.

Further confusing matters, I recognized some of the strikers as members of the University of Calgary’s Students’ Union, which had been demanding that the school increase its spending on student services and install other expensive amenities, such as hiring more staff for the Students’ Union Clubs Office and Wellness Centre, or subsidizing parking and printing services for students. Such programs can only push costs higher and force tuition up, regardless of the other circumstances.

If even the protesters don’t know who they’re protesting and why, how are the rest of us supposed to understand? I decided to try to figure it out for myself.

Finger Pointing 101

Going back to the 1960s, university students have famously displayed a passion for advancing causes through demonstrations and protesting a variety of government policies they don’t like. Since 2020, steep increases to tuition fees have triggered large-scale protests among the students who pay those fees at the University of Alberta, University of Calgary, University of British Columbia and at McGill University and Concordia Universityin Quebec, among many other schools. A freeze on tuition fees in Ontario since 2019 explains that province’s absence from the list.

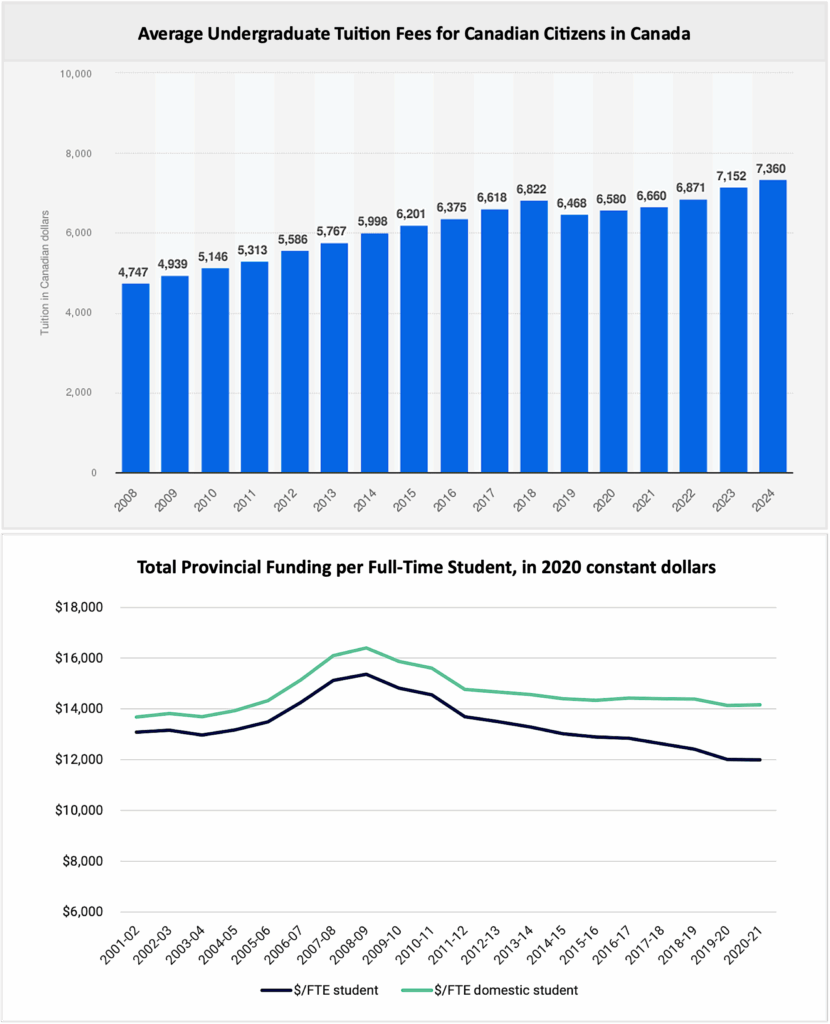

Tuition has been on the rise. According to Statistics Canada, between 2006-2007 and 2024-2025, the average undergraduate full-year tuition fee at a Canadian university grew from approximately $4,900 to $7,360. This despite Canada’s largest province freezing its fees for part of the period. The change is even more dramatic when considering that for a long stretch during the 1970s to the 1990s tuition habitually rose at a rate below inflation thanks to generous government subsidies. So what’s behind the recent increases?

While government grants have remained essentially flat, tuition fees are up. If per-student costs had remained constant, then the constant level of government funding should be sufficient to keep tuition stable, regardless of the number of students.

Today, many schools eagerly point their fingers at inflation and other cost factors allegedly outside of their control. In response to the 2023 protests, for example, University of Calgary Board of Governors Chair Mark Herman claimed the school’s “tuition and fee decision was based on a thorough analysis of the situation, including inflation and cost increases.” Given that recent tuition fee increases often outweigh recorded inflation, that excuse is easily debunked.

The other popular culprit for university administrators looking to deflect blame are provincial governments cutting post-secondary funding. Again, the evidence is unconvincing. Going back two decades, nationwide full-time equivalent (FTE) student transfer payments from provincial governments to universities have remained essentially constant, after accounting for inflation. According to a 2022 report by consulting firm Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA), the average inflation-adjusted FTE grant was just below $14,000 per domestic student in 2001-2002. In 2020-21, the average grant stood at slightly more than $14,000 per student. While the amount rose in the 2000s (largely driven by Alberta, as we shall see), that proved temporary and the long-term nationwide trend appears to have reverted to a mean of around $14,000 per student in 2020 dollars.

While government grants have remained essentially flat, tuition fees are up. All this proves is that universities are spending more per student today than in previous decades. If per-student costs had remained constant, then the constant level of government funding should be sufficient to keep tuition stable, regardless of the number of students. Instead, universities have increased both overall spending and tuition fees. At issue, then, is where all this extra spending has been going – and whether it benefits students.

Why are tuition fees rising at universities in Canada?

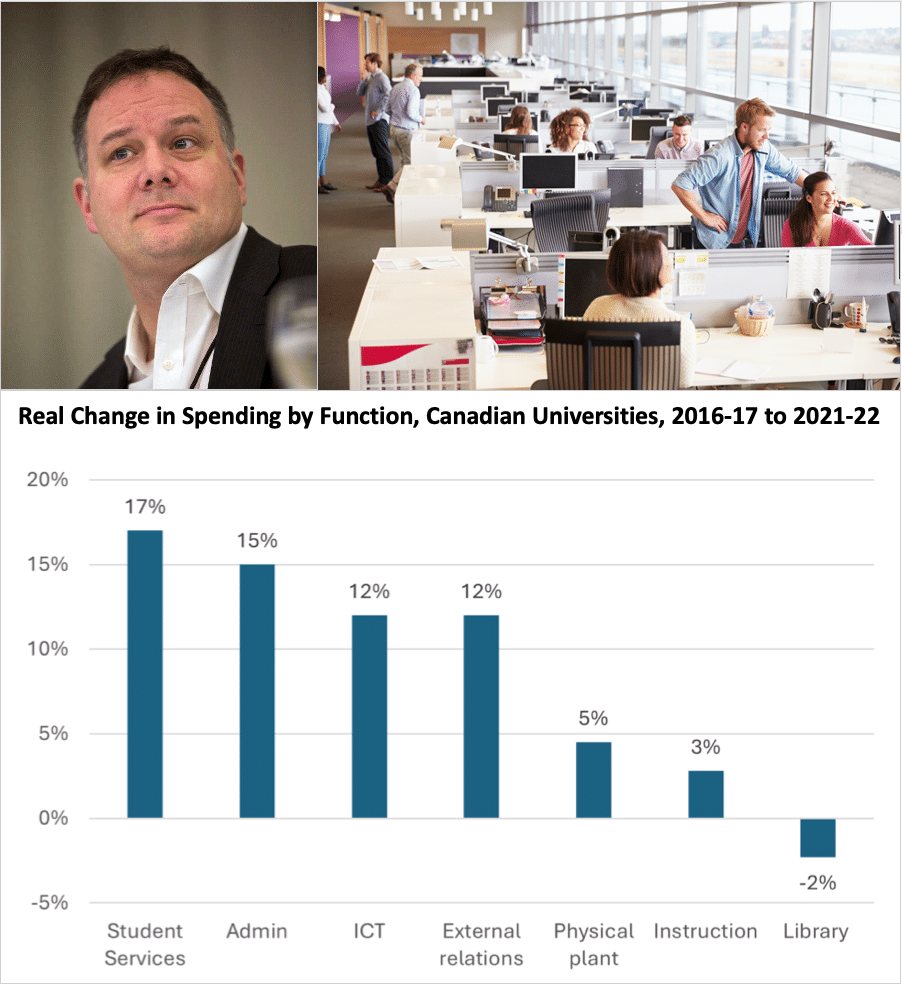

While it is common to blame inflation or cuts in government funding, the evidence shows that universities in Canada are raising fees to spend more money on non-academic bureaucracy, a phenomenon known as “administrative bloat”. For example, between the 2016-2017 and 2021-2022 academic years, spending on “Administration” grew by 15 percent nationwide in Canada. Over the same period, spending on “Instruction”, the core function of a university, grew by a mere 3 percent. As this vast army of administrators grows, the cost is passed on to students through higher tuition fees.

“Temporarily Crazed”

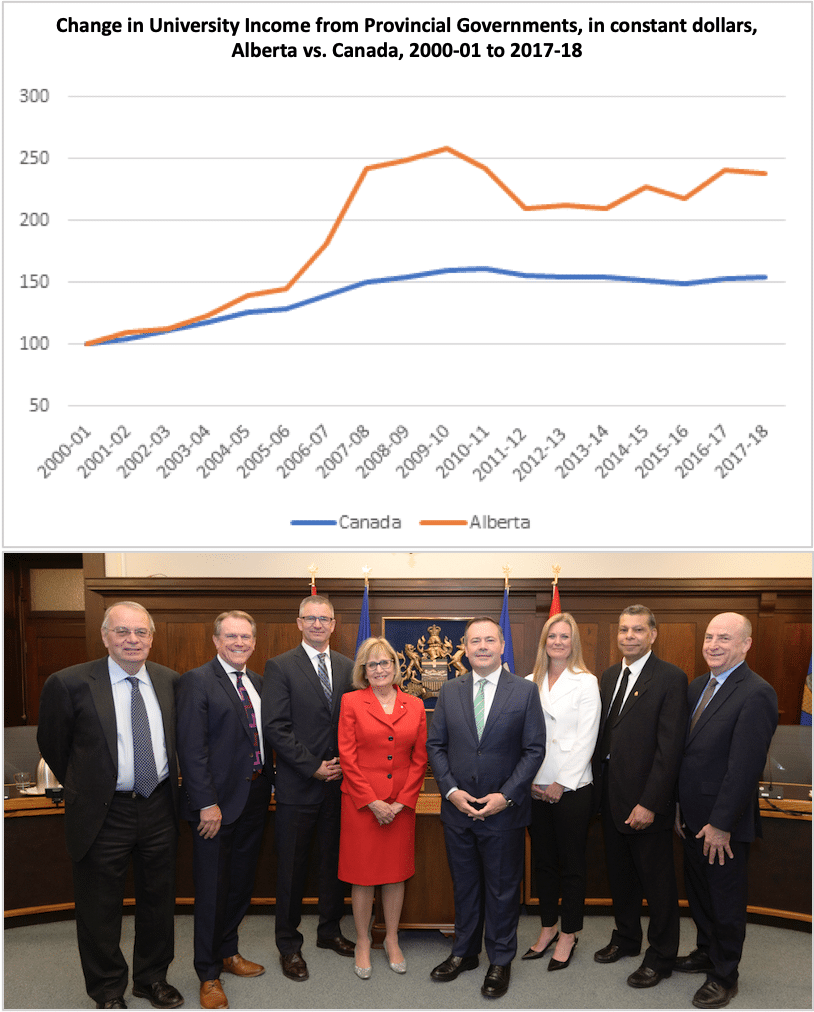

The experience of Alberta provides additional insight into the connection between government funding and tuition fees. In 2019, newly-elected Premier Jason Kenney commissioned a Blue Ribbon panel chaired by former Saskatchewan finance minister Janice MacKinnon to address Alberta’s fiscal problems. The province had just posted a $6.7 billion deficit and, after many years with no public debt, was on track to fall $50 billion into the red within a few years. The panel’s main finding was that Alberta was spending far more per-capita on social programs than any other province – especially in post-secondary education.

During the glory years of the oil and natural gas boom in the early 2000s, Alberta’s universities benefitted from massive increases in funding relative to other provinces. As Alex Usher, president of HESA and author of a well-regarded blog on university finances, pointed out in a 2019 article, the post-secondary funding bump in Alberta was the result of “a provincial government that was temporarily crazed with supercharged revenues.” As the accompanying graph shows, the result was a huge hike in the early 2000s that temporarily sent university funding into the stratosphere.

Despite the surge in public funding, however, the panel found no clear link between taxpayers’ money and specific policy goals of relevance to the public, “such as ensuring the required skills for the current and future labour market, expanding research and technology commercialization, or achieving broader societal and economic goals.” The panel also lamented “the extensive overlap and duplication among post-secondary institutions, each operating with what appears to be only limited collaboration.” It appeared the schools were spending all that money on something other than educating students as effectively and efficiently as possible.

In response to the Blue Ribbon panel’s findings, Kenney cut funding to post-secondary institutions by 12 percent while allowing universities to set their own tuition rates. Although overall annual increases were capped at 7 percent, individual programs could be increased by 10 percent per year. Most schools took full advantage of both opportunities, which explains why average tuition at the University of Calgary, for instance, rose by 33 percent between 2019-2020 and 2022-2023.

But does this mean tuition would have stayed constant, or even fallen, had the province not cut funding? Not at all. As Usher’s 2019 blog post reveals, throughout the glory days of those massive provincial funding increases, Alberta’s tuition fees still generally kept pace with the national average. “For the last quarter-century or so, Alberta has stayed pretty close to the Canadian average [for tuition fee increases],” Usher wrote. “Until 2013-14 it was above the average; since then, it has been below. But the gap was never that big either way.” Tuition fees in Alberta, then, were rising even as provincial funding was hitting unprecedented heights. And now that those increases have stalled, well…tuition is still rising.

Research from the United States points to a possible explanation for this curious phenomenon. The Bennett Hypothesis is named after William J. Bennett, the federal Secretary of Education during the Reagan Administration. In a 1987 New York Times op-ed entitled “Our Greedy Colleges”, Bennett proposed that any increase in federal university funding (mainly provided through student loans) leads universities to raise their tuition fees in order to gobble up all the available extra cash. In this way, students receive no benefit from additional government funding. Student loan policy is also at play in Canada, given Ottawa’s 2023 decision to eliminate interest on student loans, creating a massive implicit subsidy for students.

The broader lesson of the Bennett Hypothesis is that university administrators habitually act as if they are running a profit-maximizing business rather than a non-profit educational institution. Their goal is to grow as big as possible and to make as much money as possible. And with university spots typically in short supply, the best schools have substantial market power. This is why tuition rises not only when government funding falls – but also when it goes up. There is, in other words, no direct connection between government funding and tuition fees.

So where is all that extra money going?

Follow that Bloat

Last year researcher Usher took a close look at the budgeting preferences of universities on a nationwide basis. He found that between 2016-2017 and 2021-2022 the spending category of “Administration” – which comprises the non-teaching, bureaucratic operations of a university – grew by 15 percent. Only “Student Services” grew faster over this time. Curiously enough “Instruction”, the component of a university that most people would consider to be its core function, was among the slowest-growing categories, at a mere 3 percent. This top-heavy tendency for universities is widely known as “administrative bloat”.

Administrative bloat has been a problem at Canadian universities for decades and the topic of much debate on campus. In 2001, for example, the average top-tier university in Canada spent $44 million (in 2019 dollars) on central administration. By 2019 this had more than doubled to $93 million, supporting Usher’s shorter-term observations.

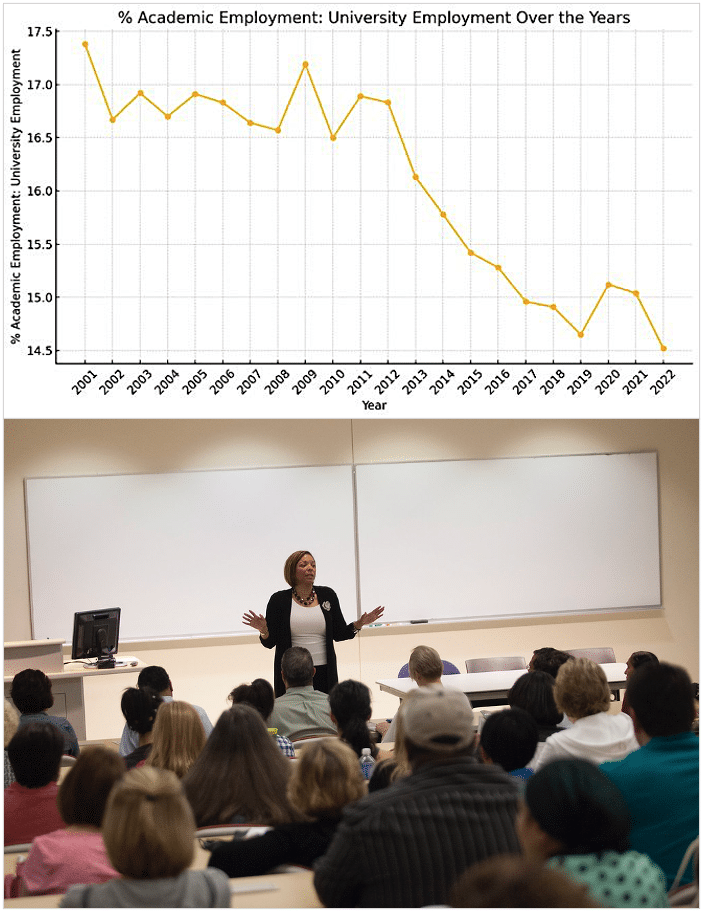

Beyond total expenditures, another way to track administrative bloat is to compare the share of academic staff – professors engaged in teaching and research – to those engaged in non-teaching, administrative pursuits. While clear and reliable numbers on this are tough to find, Usher tried to infer a figure by subtracting academic staff from the total number of employees at Canadian universities. Using two different Statistics Canada datasets, Usher’s calculations suggest the size of the non-academic cohort at universities has increased by between 85 percent and 170 percent over the past 20 years.

Teaching faculty are now paid about 10 percent less than non-academic personnel. This creates a clear incentive for professors to abandon their research specialties in favour of more lucrative bureaucratic pursuits – to the detriment of their vocation.

Initially considering these implied increases too large to be realistic, Usher tried another approach by focusing on salary data rather than head count. Here the short-term evidence suggests a substantial increase in non-academic salaries, while the long-term picture is inconclusive. Usher concludes that, “There’s a lot of contradictory data here, some of which argues strongly in favour of the bloat argument, but quite a bit of which points in the other direction.” Unable to come to a firm conclusion, he suggests, “Better data is needed to answer this question.”

Other evidence is far more suggestive of administrative bloat. Prior to the late 1990s salaries paid to ranked academic faculty were typically higher than those paid to non-academic staff. In 1980, for example, teaching faculty were paid about 20 percent more than their non-teaching colleagues. This seems a reasonable situation given the central academic purpose of a university and the many years of study required to earn a PhD. Today, however, that script has been flipped. Teaching faculty are now paid about 10 percent less than non-academic personnel. This creates a clear incentive for professors to abandon their research specialties in favour of more lucrative bureaucratic pursuits – to the detriment of their vocation.

Writing for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, researcher David Clinton reveals that between 2001 and 2022, the proportion of teaching jobs out of all campus jobs declined from 17 percent to 14.5 percent. In the same period, the proportion of support services staff more than doubled. Again, the evidence suggests academics are playing less and less of a role in the institutions originally designed around them.

Intriguing American research looks into the connection between per-student spending on administration and student services, and tuition fee increases a year later – finding a direct and positive correlation. More worrisome, both of these expenditure categories are not correlated with graduation rates. So while tuition fees keep going up, this doesn’t necessarily benefit the students paying those higher fees.

Another U.S. study looking at graduation rates found that instructional spending had a much greater impact than did administrative spending increases. It also found that spending on student services had no effect whatsoever on graduation rates – an outcome of potential interest to all those students’ union advocates demanding greater amenities on campus. If student outcomes matter, then a university should focus its resources on academics, not gold-plated administrative or student services.

The precipitous decline in Canada’s top schools by international standards further bolsters the case that Canada’s huge multi-decade run-up in administrative expenditures is at best doing nothing and at worst harming our universities’ performance and reputations. Of Canada’s 15 leading research universities, 13 have fallen in the global Quality School rankings since 2010. It seems a troubling trend.

Are provincial government funding cuts the reason for rising tuition fees in Canadian universities?

The claim that government funding cuts are driving tuition increases in higher education is unconvincing. Nationwide data from the two decades leading up to the 2020-21 academic year shows that after accounting for inflation, provincial government grants to universities have remained essentially constant, averaging around $14,000 per full-time domestic student. The experience in Alberta during its oil boom in the early 2000s shows that tuition fees continued to rise even when provincial funding reached unprecedented heights. This phenomenon can be explained by the Bennett Hypothesis, which holds that universities raise tuition to capture any available extra cash, regardless of the source. Their goal is to grow as big as possible and to make as much money as possible. There is, in other words, no direct connection between government funding and tuition fees.

“A Vast Army of Administrators”

While some level of administration is obviously necessary to operate any post-secondary institution, the current scale and role of campus bureaucracies is fundamentally different from the experience of past decades. The ranks of university administration used to be filled largely with tenured professors who would return to teaching after a few terms of service. Today the administrative ranks are largely comprised of a professional cadre of bureaucrats.

“Universities are now over-governed with high administrative and overhead costs,” pointed out economist Livio Di Matteo of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario in a 2021 Fraser Institute commentary. “There’s simply too much management with numerous deans, executive deans, vice-deans, vice-presidents, vice-provosts and ‘special advisors’ and their associated retinues of assistants, coordinators, facilitators and government liaison officers.” Of note to all those student protesters complaining about rising tuition fees, Di Matteo warns, “All the tuition revenue in the world will never be enough to feed this vast army of administrators.”

This ever-larger administrative state is increasingly displacing the university’s core academic function. As Todd Zywicki, a law professor at George Mason University, writes in The Changing of the Guard: The Political Economy of Administrative Bloat in American Higher Education, a chapter in a 2019 book, “Even as the army of bureaucrats has grown like kudzu over traditional ivy walls, full-time faculty are increasingly being displaced by adjunct professors and other part-time professors who are taking on a greater share of teaching responsibilities than in the past.” While Zywicki is writing about the American experience, his observations hold equally well for Canada. “The interesting thing about the administrative bloat in higher education,” he adds, “is literally nobody knows who all these people are or what they’re doing.”

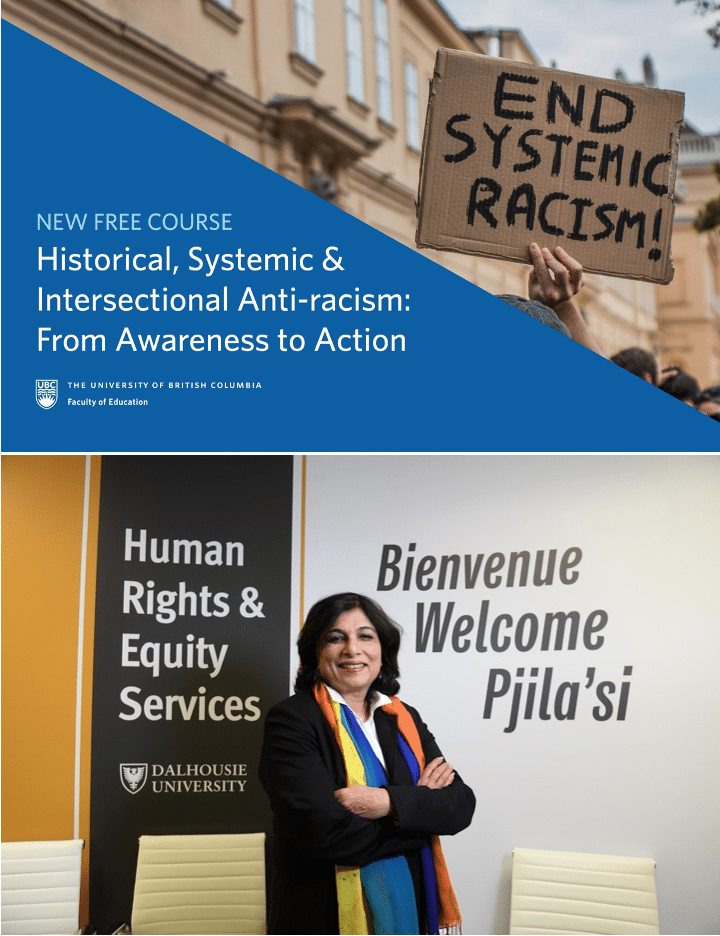

Finally, no discussion of administrative bloat today can ignore the elephant in the corner: diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). As non-teaching administrators have increasingly come to dominate university budgets, there has been a concomitant increase in resources given over to bureaucratically-driven ideological causes and programs. Writing in the National Post, Peter MacKinnon, past president of the University of Saskatchewan, draws a straight line from administrative bloat to the current infestation of DEI policies on Canadian campuses.

DEI offices and programs offer no meaningful benefit to student success or the broader university community. Rather, they damage a school’s reputation by shifting focus away from credible scientific pursuits to identity politics and victimology. This erodes a school’s commitment to academic excellence.

“When you are paid to administer and regulate, you want to do just that, and it can take you into contentious areas,” MacKinnon warns, pointing to university hiring requirements that now frequently specify the race, gender and/or sexual orientation of applicants. At the University of Saskatchewan, MacKinnon notes, it is now compulsory for the university’s 1,000 faculty members to take training in “unconscious bias” and “anti-racism” – further evidence of how a woke-minded administrative state seeks to impose its worldview. The same thing is going on at universities across Canada that have permanent DEI offices and bureaucracies, including at UBC, the University of Calgary, University of Waterloo, Western University, Dalhousie University and Thompson Rivers University.

As an earlier C2C Journal article explained, DEI offices and programs offer no meaningful benefit to student success or the broader university community. Rather, they damage a school’s reputation by shifting focus away from credible scientific pursuits to identity politics and victimology. This erodes a school’s commitment to academic excellence. The entire budget for every DEI office and administrator can be considered pure, unadulterated bloat since it adds nothing to a university’s purpose. To correct this, MacKinnon recommends that, “For every new activity and hire, the question should be asked: how does this advance teaching and research and the independence of the institution?” Following such a script would swiftly reduce bloat.

Ozempic for Universities

With universities apparently unable to restrain the growth of their administrative Leviathan, there may be little alternative but to impose discipline from the outside. This should begin with greater transparency.

William Doswell Smith is a former university administrator who now runs a website called universityfinances.ca that details the financial inefficiencies of Canada’s post-secondary institutions and the difficulty in discerning the true nature of the problem. Smith’s initial data backs the overall thesis of pervasive administrative bloat, revealing that since 2011, “Expenditure on Central Admin has increased at almost double the rate for Instruction (40% vs 22%)” at Canada’s top 25 universities.

Smith argues that any rollback of bloat must begin with better and more consistent data to help identify best practices and single out laggards. Smith’s website includes an initial attempt at a comprehensive efficiency ranking system for Canada’s top 50 universities. That said, Smith notes that senior administrators often justify their own poor spending decisions by comparing their actions with those of carefully selected peer universities that may be just as guilty of bad practices. Transparency alone is not likely to fix the problem.

What is “administrative bloat” in higher education, and how does it impact Canadian universities?

“Administrative bloat” refers to the excessive growth of non-teaching, bureaucratic staff within the higher education sector, which has outpaced the growth of academic faculty responsible for instruction and research. This has created a top-heavy administration where non-academic personnel are now paid on average 10 percent more than teaching faculty. This growth displaces the university’s core academic function, shifting resources and priorities away from student education.

A prominent example of this bloat is the growth of DEI policies and programs on Canadian campuses. These create ideologically-driven bureaucracies that add to university costs and shift focus from credible scholarly pursuits to identity politics, without offering meaningful benefit to students. Ultimately, administrative bloat harms the performance and reputation of Canadian universities, a trend reflected in the fact that 13 of Canada’s 15 leading research universities have fallen in global rankings since 2010.

Beyond better data, the real work of slashing administrative thickets will depend on substantive internal reform. In a critique of bloat in the National Post, renowned Canadian economist Jack Mintz highlights how the University of Western Australia (UWA) dramatically reduced its overall administrative expenses by virtually eliminating the school’s middle management layer. For example, the school removed its Health Faculty and pushed operational control down to the individual departments of medicine, nursing, dentistry, etc. “The focus of UWA’s reform is to reduce administrative costs and break down bureaucratic obstacles to…more creative programs,” writes Mintz. The goals, in other words, extend beyond just saving money to improving the university itself.

If internal reform of this sort isn’t forthcoming by forward-thinking administrators, then things might get far worse. Smith highlights a “Golden Rule” for universities and other non-profit institutions: that fixed costs (such as central administration) must never be allowed to rise faster than variable costs (those related to the student population). As an example of what can happen when Smith’s Golden Rule is ignored, consider the fate of Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario.

In early 2021 Laurentian announced it was seeking bankruptcy protection under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act, under which a court-appointed manager directs the operations of the delinquent organization. Laurentian then eliminated 76 academic programs, terminated 195 staff and faculty, and ended its relationships with three nearby schools. This unprecedented use of creditor protection prompted the provincial Auditor-General, Bonnie Lysak, to investigate. Her final report found that while external factors such as Covid-19 and demographics played roles, the primary cause of the school’s financial crisis were bad decisions by senior administrators. In defiance of an earlier financial report, they had ploughed ahead with an ill-considered expansion project that included piling on $87 million in debt. The administrators’ big dreams essentially bankrupted the university.

When student protesters at the University of Calgary sit down to plan their next interruption to my education, they should understand the real source of the problem. It’s right in front of them: the solution to higher tuition is fewer administrators.

Many other Canadian universities and colleges are facing a similar financial reckoning. One cause is their increasing reliance on foreign students, whose tuition fees are largely unregulated and can thus be raised at will. But the Mark Carney government’s dramatic reduction in international student permits has caused hardships for these schools as well. Multiple B.C. institutions, including UBC and Simon Fraser University, have been hit hard.

In Ontario, the lengthy tuition freeze has slowly starved many schools of funds; combined with the international student situation, this has precipitated a financial crisis. Fanshawe College in London is laying off 400 full-time employees, about one-third of its staff. It is also ending 40 academic programs effective this fall and bracing for a 30 percent drop in total student enrollment. Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo is also facing a financial crunch. The school’s response has been to rationalize some administrative expenses, notably by shutting down its high-profile Centre for Indigegogy, which was meant to promote Indigenous “ways of knowing”. As a result, Laurier can now be considered a tiny bit less bloated. Similar but far more sweeping action will be needed at universities all across the country.

The overall lesson seems clear: if universities refuse to correct the out-of-control growth of their administrations, then fiscal discipline will eventually be forced upon them. This could come in the form of a sharp reduction in government funding, as was the case in Alberta, or the slow-motion version occurring in the wake of Ontario’s six-year-long tuition freeze. Or it could be something even sharper and more traumatic, as Laurentian’s woes demonstrate. Regardless, a reckoning is coming for these bloated, profligate schools. And it is here that students upset over rising tuition fees can make themselves useful.

The true cause of increasing tuition fees is not to be found in government funding decisions. As we have seen, on average inflation-adjusted FTE funding in Canada is about the same today as it was two decades ago. The big difference between then and now is in the size of school administrations, which have grown at unprecedented rates, and now imperil the true purpose of the university as an academic institution. So when student protesters at the University of Calgary sit down to plan their next interruption to my education, they should understand the real source of the problem. It’s right in front of them: the solution to higher tuition is fewer administrators.

Jonathan Barazzutti is an economics student at the University of Calgary. He was the winner of the 2nd Annual Patricia Trottier and Gwyn Morgan Student Essay Contest co-sponsored by C2C Journal.

Source of main image: Shutterstock/AI Image.