Like the late comedian Rodney Dangerfield, the free market gets no respect. Even when politicians claim to be for freer markets, they really are not. Some quick examples: Prime Minister Mark Carney saying we must get federal spending under control but then in last week’s federal budget increasing spending and borrowing; Ontario’s Progressive Conservative Premier, Doug Ford, claiming to be fiscally conservative while outspending the previous Liberal government he denounced as fiscally reckless; politicians of various stripes purporting to be for free trade while supporting all sorts of protectionist policies; federal agencies supposedly promoting competition but instead imposing widespread restrictions. The list goes on.

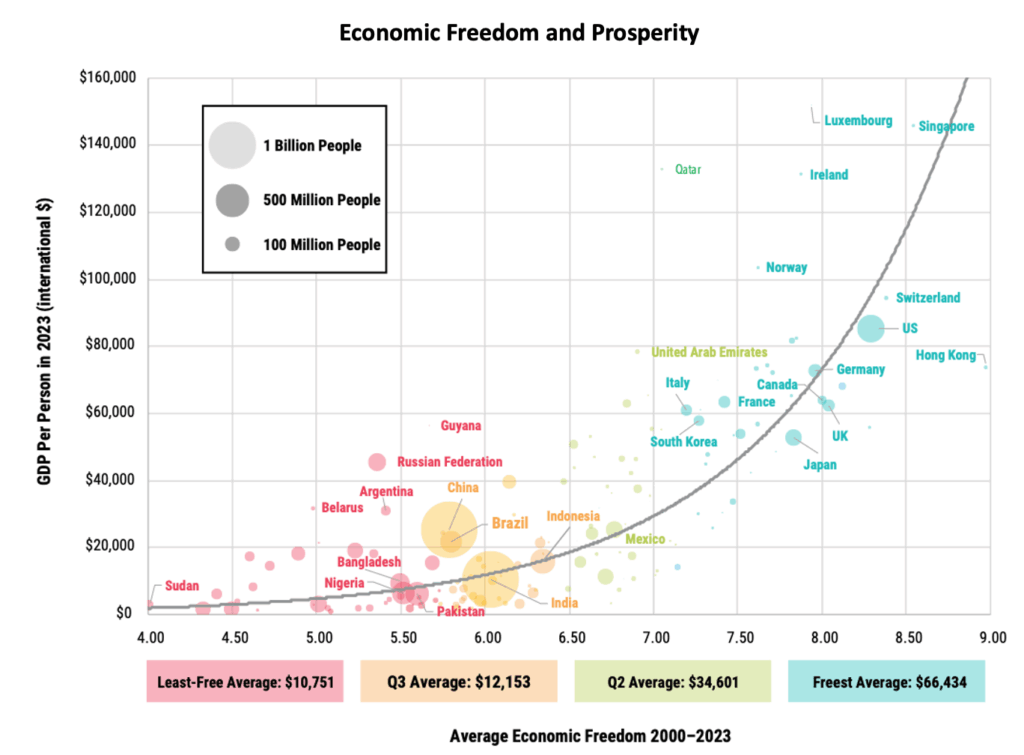

Yet while getting no respect, free markets – or “capitalism” – have delivered exceptional results over a period spanning more than 200 years and reaching around the globe to every country where they’ve been tried. The Fraser Institute’s latest annual Economic Freedom of the World report ranks 165 jurisdictions based on government consumption, tax rates, state ownership of assets, property rights, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, the degree of economic regulation and other criteria.

The report finds that in the 25 percent of jurisdictions with the most economic freedom as compared to the 25 percent with the least, average per capita income is 6.2 times higher, income for the poorest decile is 7.8 times greater, and life expectancy is 17 years longer. Conversely, the least economically free jurisdictions suffer poverty rates about 25 times greater and infant mortality rates nearly 10 times higher than the most economically free jurisdictions.

Keep in mind that some of these places started off at essentially the same level. North Korea versus South Korea or East Berlin versus West Berlin during the Cold War most drastically contrast the disasters of government control versus the benefits of capitalism. But there are other examples too, such as the stunning collapse of socialist Venezuela versus the miraculous rise of capitalist Poland in the past two decades.

Yet despite the astonishing economic progress and improvements to standards of living that are clearly attributable to free markets, politicians, academics, activists, pundits and journalists generally treat free markets unfairly and often with contempt. Some of their attacks are made out of self-interest, others out of ignorance. Either way, the misguided attacks are not new. “There is a striking contrast,” the Nobel Prize-winning U.S. economist Milton Friedman observed in 1966, “between the record of performance of the free market and the attitudes held toward the free market by both the public at large and especially by the intellectual community.”

One reason the free market gets such bad press, according to Friedman, is that this immense force for good has no media promoter – no agent, if you will. “There are always government officials who give out press handouts to glorify the agencies they represent or to take credit for what occurs,” Friedman wrote. “There is no press agent who gives out handouts about the anonymous workings of the free market.” Today’s enemies of free markets, by contrast, have plenty of press agents.

It is time to give the free market the respect it deserves, to give the market its very own agent. In this essay, I will start by deflating four myths created by critics of free markets.

What is the relationship between economic freedom and prosperity?

Research has established a strong link between a country’s overall economic freedom – a key enabler of the free market – and the economic well-being of its citizens. The Fraser Institute’s annual Economic Freedom of the World report, which ranks 165 jurisdictions on metrics like property rights, tax rates and freedom to trade, provides clear data.

When comparing the 25 percent of jurisdictions with the most economic freedom to the 25 percent with the least, the most-free jurisdictions have average per capita income 6.2 times higher, income for the poorest decile 7.8 times greater, and life expectancy 17 years longer. Conversely, the least economically free jurisdictions experience poverty rates about 25 times greater and infant mortality rates nearly 10 times higher.

Myth #1: Unions and Government Regulation Protect Workers

A common criticism of free-market capitalism is that it is only good for the capitalists who get richer by exploiting workers and grinding them under their heels. This view is mistaken: the average worker in a modern economy fares better than the average worker or agrarian peasant at any other time in history. But why is this? What protects workers from exploitation?

As Milton and Rose Friedman explain in their classic book Free to Choose, one possible answer is that unions protect workers. An inescapable problem with this answer is that in order to raise the price of something, such as labour wages, there must be either more demand or less supply. But unions do not increase the demand for labour; that can only come from employers. Unions actually do the opposite. That is because unionization reduces the incentives for workers to be productive by linking their compensation and job security to tenure (time accumulated in that job or with that company or organization) instead of productive output.

Have some respect: Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman noted the “striking contrast” between the performance of free markets and the respect they’re given; in Free to Choose, co-authored with his wife Rose, they argue that capitalism, freedom and prosperity are inextricably linked. (Source of left photo: Natalia Bargel, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Have some respect: Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman noted the “striking contrast” between the performance of free markets and the respect they’re given; in Free to Choose, co-authored with his wife Rose, they argue that capitalism, freedom and prosperity are inextricably linked. (Source of left photo: Natalia Bargel, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)Unions can therefore only raise wages by limiting the supply of labour. As the Friedmans put it, the basic source of union power is “the ability to keep down the number of jobs available, or equivalently, to keep down the number of persons available for a class of jobs…generally with assistance from government.”

Last year, at the behest of unions, the federal Liberal and Manitoba NDP governments enacted separate legislation to prohibit the hiring of replacement workers (habitually vilified as “scabs” by hostile unions, academics and journalists) during union strikes. Other anti-competitive policies unions support include prescriptive labour regulations, tariffs and other protectionist policies, occupational licensing, minimum wage laws, and restricted tendering policies that give unions preferred or exclusive access to government contracts.

A minimum wage of, say, $17 per hour, is a law that tells employers they are not allowed to hire workers whose productive capacity is only $14, $15 or $16 per hour or for tasks that, regardless of the worker’s productivity, are only worth that much.

Contrary to the narrative emanating from unions’ headquarters and repeated by the media, the main effect of unions is to benefit certain privileged workers. In thereby restricting the labour supply, they oppress the most disadvantaged members of the labour force by pushing them off the economic ladder. The overall effect of unions is not to protect workers but to create a net economic loss as economic production declines and the least privileged workers are shut out of the labour market.

If not unions, another possible answer to the question “Who protects the worker?” is government. After all, there are minimum wage laws, laws around overtime pay and many other workplace regulations with similar economic intent and effects. But what are the actual effects of such policies?

When the minimum wage is increased, some workers’ wages will rise, but many other workers will lose their jobs. A minimum wage of, say, $17 per hour, is a law that tells employers they are not allowed to hire workers whose productive capacity is only $14, $15 or $16 per hour or for tasks that, regardless of the worker’s productivity, are only worth that much – unless that employer is willing to lose money. Instead, employers in that situation are most likely to replace low-productivity labour with machinery and technology, or simply go without. The Canadian experience has shown that workers priced out of jobs by minimum wage increases include teenagers who do not have much job experience, recent immigrants, workers who have physical or cognitive disabilities, and many others who have a lesser ability to generate output.

Comprehensive literature reviews confirm the negative employment effects of minimum wage laws and that these are concentrated on the most disadvantaged members of the labour force. In fact, even many workers whose wages rise because of the minimum wage are worse off, because to absorb the higher cost, employers must reduce non-wage benefits – benefits that many workers prefer to higher wages.

In reality, neither unions nor governments protect workers. What protects workers is free-market competition. Walmart employees, for example, are protected by Canadian Tire, Dollarama and Staples – Walmart’s competitors and rival employers. If Walmart tries to exploit its employees by paying less than they are worth – for example, by paying employees worth $20 per hour only $16 – its competitors would happily expand and hire those underpriced workers away from Walmart at $17, or $18, $19 or even $19.90 per hour, because by doing so they could increase their profits.

Myth #2: Government Protects Consumers

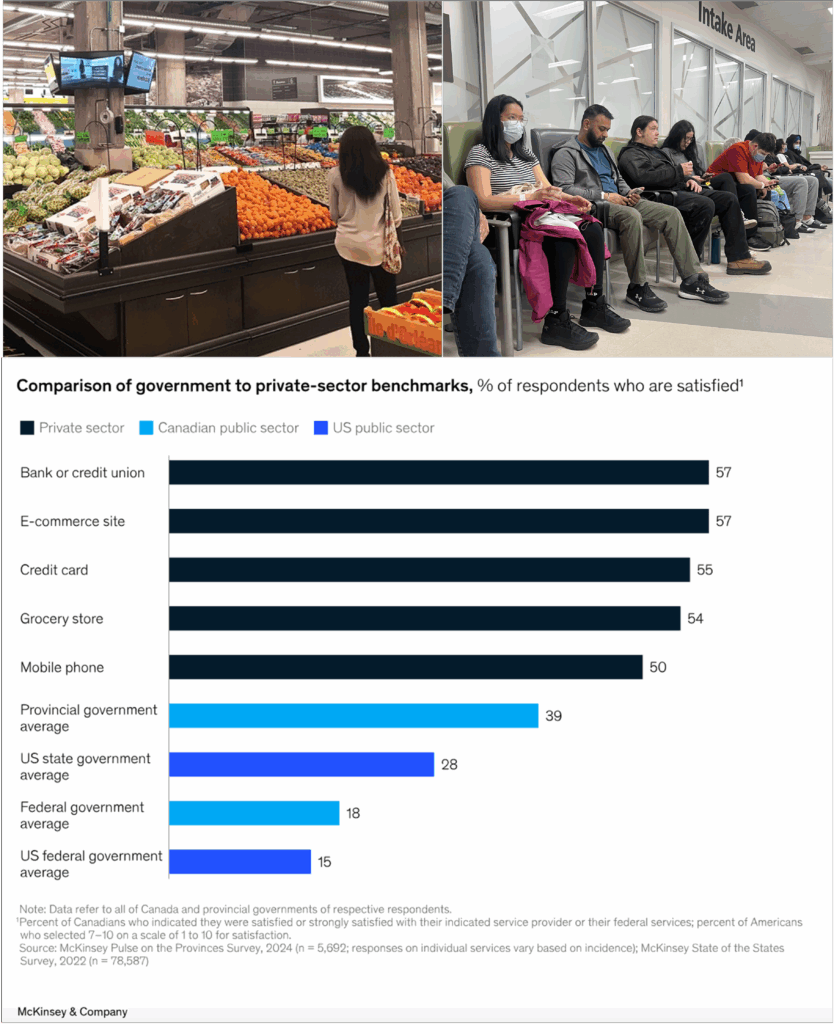

The other segment said to be left behind by free-market capitalism is the consumer. Those who think capitalist businesses can easily exploit workers will naturally believe they also exploit consumers, and that government must step in to stop the exploitation. Anyone who thinks government protects the consumer, however, should look at the recent record of government.

Canada’s federal government (along with the provinces) oversees a health-care system in which the average wait time for orthopaedic surgery is 57 weeks, gives agricultural producers artificial monopoly rights worth $48 billion, has everyone drinking through paper straws that dissolve in our drinks, recently mused about helping grocery shoppers by imposing special taxation on grocery stores, and proposes to ban the sale of new vehicles powered by internal combustion engines which, data earlier this year show, account for more than 90 percent of Canada’s light-duty vehicle market. In all these instances of government “protection”, the Canadian consumer is the loser.

More evidence against the theory of government as providing consumer protection was presented in a recent McKinsey & Company article which compared Canadian consumers’ satisfaction with government-provided services against services provided by the private sector. Despite being subject to constant criticism and political attacks in recent years, banks and credit unions scored a 57 percent satisfaction rate and grocery stores scored 54 percent. Similarly, 57 percent of Canadians reported being satisfied with e-commerce sites and 50 percent with their mobile phone service.

In fact, even when the government appears to be providing consumer protection by promoting private-sector competition, it does more harm than good. Take the recent case of politicians and activists accusing grocery stores of effectively fixing prices. Loblaw is currently being forced to pay $500 million to consumers because of a class-action lawsuit for allegedly colluding with competitors to raise bread prices. Isn’t this a case of government protecting consumers by ensuring competition? The answer is no.

Notwithstanding possible coordination between competitors on bread prices, the grocery market as a whole is fiercely competitive. This means stores with high bread prices would only be able to retain customers if they outperformed stores with cheaper bread on other criteria such as quality, service or convenience, or offered enough other cheaper products that their higher-priced bread didn’t matter to most consumers. Grocery stores’ profits as a percentage of sales are in the low single digits; there’s simply no room for government to “protect” consumers by dictating what certain stores can charge for bread.

In reality, the source of consumer protection is the same as the source of protection for workers: free markets and competition. As long as the market is competitive in the sense that government is not imposing barriers to entry by new competitors, consumers will be free to choose among different options and will be protected from exploitation by producers.

What is the most effective protection for workers in the marketplace?

The best protector of workers is free market competition. Just as competition is the true source ofconsumer protection, the market itself is more effective than unions or government regulation. For example, a Walmart employee’s wages are indirectly protected by rival employers like Canadian Tire, Dollarama and Staples, who have a direct profit incentive to hire a productive but underpaid employee away from their competitors.

Unions, by contrast, raise wages for certain privileged workers by limiting the supply of labor, a manipulation of supply and demand, creating a cartel effect and reducing the number of jobs available to disadvantaged workers. Similarly, government policies like the minimum wage price low-productivity workers like teenagers or unskilled labourers, including some immigrants, out of jobs.

Myth #3: Free Markets Enable or Increase Racism

Critics of free-market capitalism often charge that this economic system facilitates and even encourages widespread and systemic discrimination against visible minorities, women and other disadvantaged groups. Therefore, capitalism must be constrained by government through anti-discrimination laws, equal-pay-for-work-of-equal-value laws to close the gender pay gap, and all sorts of human rights legislation to reduce racism and protect minorities.

The logic behind Becker’s insight, explained in his 1971 book The Economics of Discrimination, is that an employer who refuses to hire workers based on race will have a smaller pool of potential workers to hire from, and so must either pay a higher price for workers or settle for less productive ones from the ‘preferred’ race.

Yet “it is a striking historical fact,” Friedman observed in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, “that the development of capitalism has been accompanied by a major reduction in the extent to which particular religious, racial, or social groups have…been discriminated against.”

Indeed, a key insight from Gary Becker – a colleague of Friedman’s at the University of Chicago and winner of the 1992 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for extending microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour – was that contrary to the claims Marxists often make, in a market economy racial discrimination imposes a financial cost on the people doing the discriminating.

The logic behind Becker’s insight, explained in his 1971 book The Economics of Discrimination, is that an employer who refuses to hire workers based on race will have a smaller pool of potential workers to hire from, and so must either pay a higher price for workers or settle for less productive ones from the “preferred” race. Similarly, a worker who refuses to work for employers of a certain race will have fewer job opportunities. A consumer who does not buy from people of a certain race will have fewer places to shop and will on average face higher prices. And a business owner who refuses to serve people of a certain race will have fewer potential customers. Which doesn’t mean this will never happen – but it means that the source of such discrimination is not the free market, but human animosity and ignorance.

Reducing racism: In The Economics of Discrimination, Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker argued that racial discrimination in a free-market economy carries a financial cost for those doing the discriminating; for companies, it limits their labour pool and customer base while for consumers and workers it limits choice and opportunity. (Source of photo: (University of Chicago)

Reducing racism: In The Economics of Discrimination, Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker argued that racial discrimination in a free-market economy carries a financial cost for those doing the discriminating; for companies, it limits their labour pool and customer base while for consumers and workers it limits choice and opportunity. (Source of photo: (University of Chicago)In a free market, then, racist behaviour is a costly competitive disadvantage for businesses. The corollary is that in competitive sectors where there are no government barriers to entry – such as apartheid or segregation – the incidence of racism is greatly reduced. Becker’s book also showed that in more competitive industries there tends to be less racial discrimination because racist companies lose market share to companies that are not racist. Conversely, in industries that are more heavily regulated by government and therefore less competitive, discrimination is more common.

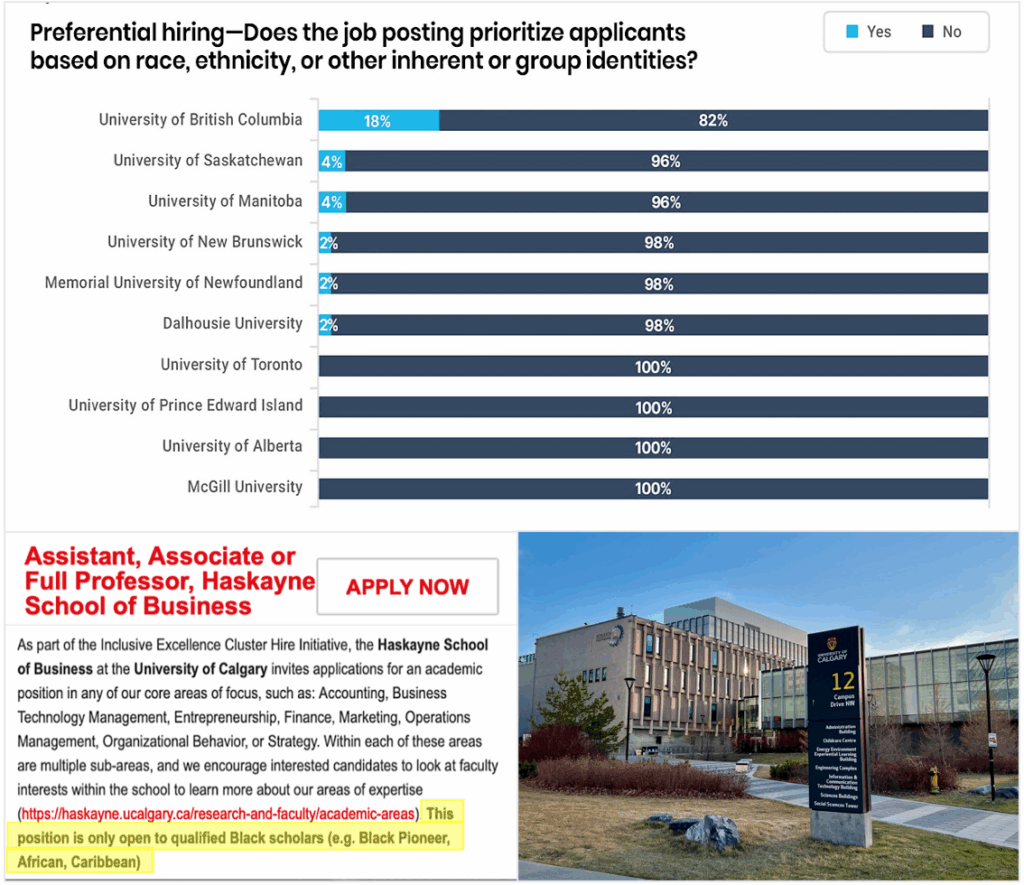

Since Becker’s trailblazing work, further solid evidence has been accumulated that racism and other forms of discrimination are less common in the competitive private sector than in sectors with more government control.

People who currently read job postings from private or public-sector employers will often encounter phrases like, “We are an equity-seeking employer and encourage applications from women and minorities.” Note that looking for such people does not constitute discrimination. Actual discrimination occurs when the employer gives preferential treatment to people based on race or another identity characteristic, or worse, outright excludes people from consideration based on those characteristics. An example would be a job posting that said something like, “This position is restricted to individuals who self-identify as a woman, racialized minority or Indigenous person.”

Such phrases in job postings may seem relatively rare, so where might they be found? The phenomenon was illuminated in a groundbreaking C2C article in 2022 that revealed open racial and gender discrimination through reserved job postings at the University of Calgary. It was confirmed by a follow-up analysis released this year by the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, which calculated that about one in every 30 job postings at Canadian universities outright exclude people from the hiring process based on race or another identity characteristic. At the University of British Columbia, it is nearly one in every five job postings. While large, publicly funded Canadian universities engage in overt hiring discrimination, it would be difficult to imagine a large restaurant chain doing the same – an example of Becker’s point that free markets have a mitigating or even preventative effect on racism, while government control can enable it.

Myth #4: Free Markets are Bad for the Environment and Climate

It is widely claimed – and believed – that capitalism is destroying the global environment and plunging us into a climate-change crisis. What is the reality?

The evidence is clear that the main sources of the environmental cleanliness we enjoy today are capitalism and free markets. Modern cities were largely cleaned by the adoption of automobiles, which rid the streets of horses and their copious urine and manure that attracted vermin and spread disease. The invention of refrigerators improved health and cleanliness by curtailing bacteria growth in food. The production and refining of crude oil beginning in the later 1800s all but wiped out the U.S. East Coast whaling industry as people switched from whale oil to kerosene for lamp fuel.

On a larger scale, the story has been the same. During the Cold War, the Communist world suffered far worse pollution than Western countries. In 1990, the Washington Post reported that Bitterfeld, an East German city, was “the dirtiest place in the most polluted country in the world, according to government statistics and Greenpeace.” An East German automobile – which typically used a two-stroke engine akin to that of a snowmobile, with no emission controls at all – spewed about 100 times more carbon monoxide into the atmosphere than Western-made cars. East Germany as a whole emitted five times as much sulphur dioxide into the air as West Germany, which had four times the population.

One of Friedman’s famous observations concerning the differences between free markets and government control was that nobody spends somebody else’s money as carefully as he spends his own. Along those same lines, he observed that capitalism and private ownership were good for the environment because “nobody takes care of somebody else’s property as well as he takes care of his own.” A 2014 Fraser Institute study found that countries with the most economic freedom had cleaner air than those with the least.

Climate change is a different and more complex issue than conventional environmental problems, but on this issue too it is clear the free market offers humanity the best protection. Thanks to technological and economic advances in recent decades, the death rates from floods, droughts, storms, wildfires and extreme temperatures have fallen to about 1 percent of what they were a century ago.

Does free-market capitalism encourage or enable racism?

No, the historical evidence suggests the opposite. The development of capitalism has been accompanied by a major reduction in discrimination on the basis of race, sex and other immutable characteristics. Nobel Prize-winning University of Chicago economist Gary Becker observed that racial discrimination in a market economy imposes a financial cost on the people doing the discriminating. An employer who refuses to hire people based on race has a smaller pool of potential workers and must either pay higher prices for labour or settle for less productive workers. Likewise, a business owner who refuses to serve customers of a certain race will have fewer potential customers.

In a free market, racist or other discriminatory behaviour becomes a costly competitive disadvantage. As a result, discrimination is less common in the competitive private sector than it is in sectors with more government control. Moreover, even worst-case projections of the future effects of climate change in coming generations are no cause for panic or repudiation of free markets. One worst-case scenario forecasts that, relative to a hypothetical planet without climate change, global GDP per capita (a good indicator of material standards of living) might be about 16.5 percent lower by the year 2200. That is significant, but just as a 16.5 percent cut to material wealth today would still leave the average person with a standard of living far exceeding that of the average person 175 years ago, we should expect people living in the year 2200 to have standards of living far exceeding what is enjoyed today – even if those people are 16.5 percent poorer than they otherwise would be.

Indeed, assuming average annual worldwide economic growth of 2 percent, under the above scenario it would instead take until 2208 for the average person to attain the standard of living he or she otherwise would have reached by 2200. The damages of projected climate change are, therefore, almost a rounding error when set against the standard of living improvements that free markets can generate.

The Myths Go On

Many other myths about the free market persist despite evidence to the contrary.

There are efforts in various provinces to preserve monopoly or near-monopoly status for government-run school systems even in the face of abundant evidence from Canada as well as literature reviews from the United States showing that providing parents with school choice greatly benefits schoolchildren.

During the recession following the 2008 financial crisis, governments spent heavily to ‘stimulate’ the economy, but multiple analyses show the effect was to waste money, not help economic recovery.

Canada’s government-run health-care system is a political sacred cow, but despite Canada being among the highest-spending nations, our health-care system performs badly when measured against peers. The notable difference between health-care policy in Canada and other high-income countries with universal coverage: the others all allow and often even encourage private insurance markets and service delivery for medically necessary health care.

It is often said that government intervention is needed to rescue the economy in times of crisis, such as in the aftermath of a natural disaster or stock market crash. But examples from history show the opposite to be true: government meddling prolongs the negative impacts of the disaster, while free markets hasten recovery.

During the recession following the 2008 financial crisis, governments spent heavily to “stimulate” the economy, but multiple analyses show the effect was to waste money, not help economic recovery. Canada, whose Conservative government spent less during this time than many other Western countries, came out of the crisis in better shape.

The power of the free market to improve standards of living and curtail social ills is clear. It is time the free market was paid the respect it deserves.

Toronto-based Matthew Lau has written on business, politics and economics for the National Post, Fraser Institute and other publications and think-tanks.

Sources of photos in main image: (left) Tinker Sailor Soldier Spy, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; (right) snorpey, licensed under CC BY 2.0.