In the midst of President Donald Trump’s deeply harmful tariff rampage, the United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) provides a vital respite for exempted goods, covering the large majority of items traded between the two countries, steel and aluminum products being prominent, steeply tariffed exceptions. But the tenure of that trilateral treaty is increasingly uncertain as internal preparations begin for next year’s mandatory renegotiation of the entire deal. Among the most contentious issues are restrictions on the importation of U.S. dairy products, eggs and poultry under Canada’s agricultural supply management system.

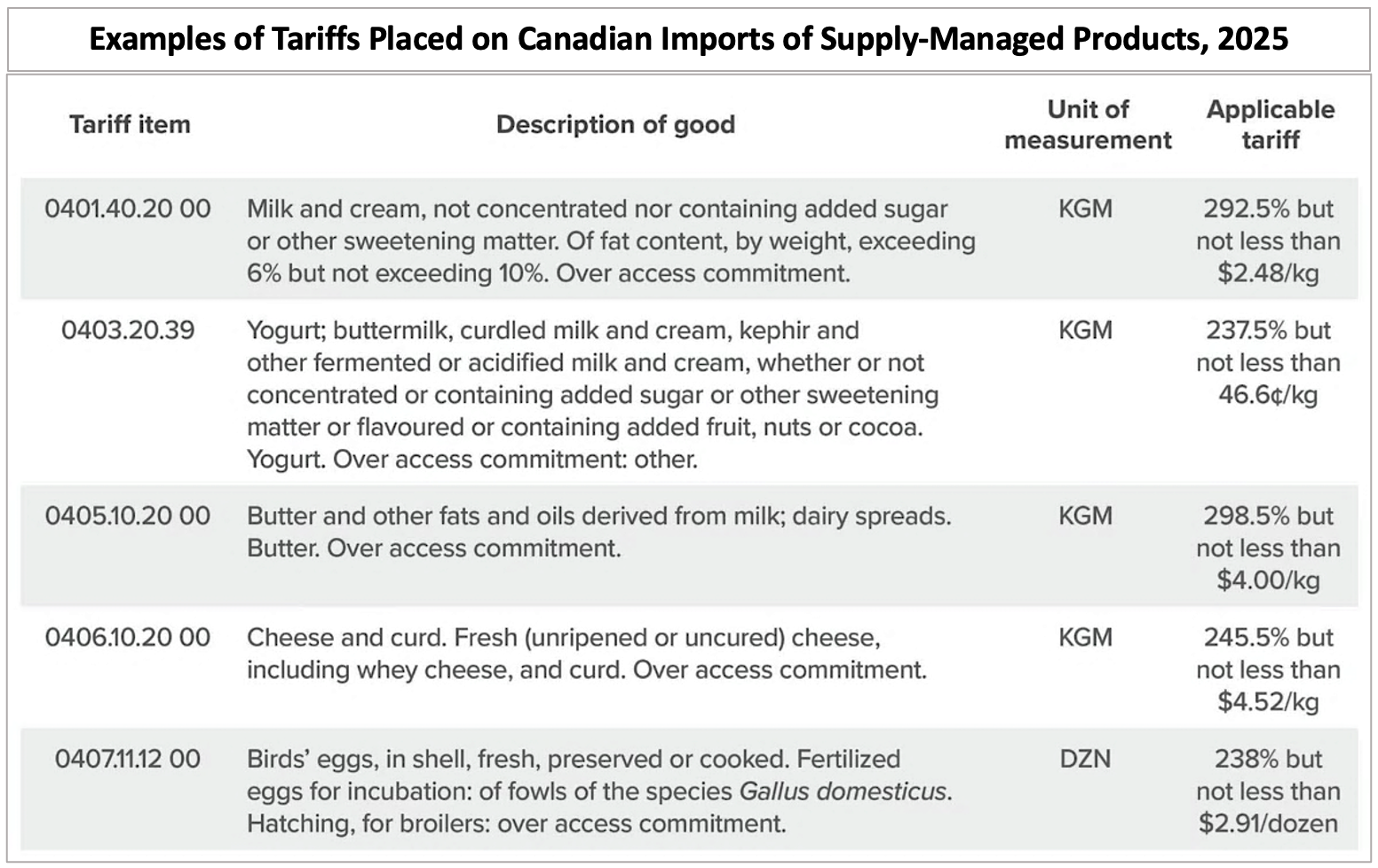

Supply management uses a web of farm production quotas, fixed farmgate prices, strict import limits and import tariffs of nearly 300 percent. The primary goal of this system is protecting designated Canadian producers by “matching” supply with expected domestic demand. Under supply management, each licensed Canadian farm receives a quota setting out how much it can produce. Given the thousands of farmers spread across the country, combined with the fact that the quotas are specific to milk products, eggs, chickens and turkeys, the bureaucracy (and number of bureaucrats) required is incomprehensibly huge. And extremely costly. Department of Agri-Food transfer payments for fiscal 2025 included $4.8 billion merely to “compensate” supply-managed farmers and processors who recently became exposed to slightly greater international competition.

There’s a lot wrong with supply management – enough to easily fill a book about it – but one of its foremost problems is that the bureaucrats often get the fundamentals wrong. Canada’s most recent chicken production cycle (ending May 31, 2025), for example, created among the worst supply shortfalls since the early 1970s. But those preset production quotas prevented supply-managed Canadian farmers from responding to meet the unforeseen demand, leaving consumers with higher grocery bills for suddenly scarce Canadian poultry and pricey eleventh-hour imports.

Over a century of socialist failures in dozens of countries worldwide have conclusively proven that central economic planning inevitably fails, creating punishing shortages and/or stratospheric prices. Why, then, should Ottawa’s attempts to “manage” the supply of a few particular food categories turn out any better? The dysfunction isn’t limited to chickens. Eggs also grew short last year and prices rose. Canadian farmers again were prevented from responding to market conditions. Instead, the system’s strange shortage allocation program kicked in. Our trading partners took full advantage, with imports topping 14 million dozen eggs by mid-year. Chile, for example, is on track to double its exports. But why not just let any Canadian farm family that wants to produce as many eggs as they can sell? The added competition would quickly lower prices.

How does Canada’s agricultural supply management system function, and what are its economic impacts on Canadian consumers and farmers?

Canada’s agricultural supply management uses a system of assigned production quotas, fixed farmgate prices, and import quotas plus tariffs approaching 300 percent to control the designated agricultural sectors of dairy, poultry and eggs. While supply management aims to align production with expected domestic demand, it frequently results in market imbalances. Unlike producers in a free-market economy, supply-managed farmers are prevented from responding to market signals. For example, the chicken production cycle ending May 31, 2025, caused significant supply shortfalls, driving prices higher. Yet when a supply-managed farmer’s production exceeds their quota, any surplus must be destroyed; every year, Canadian dairy farmers dump enough milk to supply 4.2 million people. A Fraser Institute report calculates that Canada’s supply management system imposes an additional $375 in annual costs on the average Canadian household, needlessly driving up food prices.

The costs to Canadian consumers of this mad system of price-fixing mismanagement are steep. A Fraser Institute report states that supply management costs the average Canadian household an additional $375 in needless food expenditures annually. And since lower-income Canadians spend a much higher proportion of their incomes on food than higher-income earners, the impact on them is several times as severe.

The supply management system also strangles consumer choice. European countries produce literally thousands of fine cheeses vastly superior to the “industrial” cheese we Canadians mostly consume – and at lower prices. But you wouldn’t know it, with many imported cheeses currently costing in the neighbourhood of $60 per kg. That is because anything above a meagre import quota assigned to exporting countries is subjected to a Canadian import tariff of 245.5 percent. In Switzerland, one of the world’s most eye-poppingly expensive countries, where a thimble-sized coffee will set you back $9, premium cheeses are barely half the price you’ll find at Loblaws or Safeway.

Canadian ranchers can raise as many cows as their land will support, pig farmers can respond to market signals by adding capacity, and crop farmers routinely switch between wheat, barley, canola, peas or anything else their land will produce in response to fluctuating supply and demand. It’s what producers in all sectors do in a free-market economy.

It comes as no surprise that Canada’s supply-managed farmers are anxious to protect their monopoly. The Dairy Farmers of Canada publication “What Supply Management Means for Canadians” offers the following nebulous justifications:

- “The right amount of food is produced to meet Canadian needs”;

- “Supply management offers a fair return for producers”; and

- “Foreign imports of dairy are limited to ensure Canadians have access to homegrown food.”

They’re certainly right about the middle point, with Ottawa ratcheting the farmgate prices of supply-managed foods ever-upward, but the rest is gobbledegook. Is there a shred of evidence Canadians are being denied the “right amount” of bread, tuna, asparagus or applesauce? Of course not; the market readily supplies all these and many thousands of other non-supply-managed foods. What might “too much” milk look like, anyway? And does any Canadian lack “access” to “homegrown” hamburger meat? Again, of course not. We might lack “access” to “homegrown” bananas or avocados, but things we can’t produce efficiently should be imported. That’s why we have an international trading system anchored by formal agreements.

Remember, Canadian ranchers can raise as many cows as their land will support, pig farmers can respond to market signals by adding capacity, and crop farmers routinely switch between wheat, barley, canola, peas or anything else their land will produce in response to fluctuating supply and demand. It’s what producers in all sectors do in a free-market economy.

Like all price-fixing systems, Canada’s supply management provides only the illusion of stability and security. Dairy cattle, for example, may be milked by machines, but they themselves are not machines, so a cow’s milk production varies. We’ve seen above what happens when production falls short. But perversely, if a farmer manages to get more milk out of his cows than his quota, there’s no reward: the excess must be dumped. And these are not trivial volumes; last year, Canada’s dairy farmers dumped enough milk to feed 4.2 million people. Talk about built-in disincentives to innovate, work hard and make one’s cows and farming operation more efficient and productive.

Instead, Canada’s supply management racket has become largely about the quota. When governments act to limit any item, its value always rises. Scarce dairy quotas, by their very nature, have become a valuable commodity, selling for effectively over $25,000 per cow, making a 100-cow dairy farm quota worth at least $2.5 million. So it’s not surprising that many of Canada’s dairy farmers – now down to about 9,300 from over 120,000 in the early 1970s – take the cash and sell the property.

Why does the Canadian federal government maintain agricultural supply management despite the economic costs and trade risks?

Agriculture isn’t the only sector where government-regulated quotas have become very valuable. The West Coast fishery is another prime example. Commercial fishery quotas for salmon and halibut have become valuable commodities worth millions of dollars. That’s completely out of reach for independent fishers, turning them into de facto employees of quota-holders.

While of relatively limited national importance, agricultural supply management is of major political significance in Quebec, whose farmers own a disproportionately large share of Canada’s quotas. Montreal Economic Institute Senior Economist Vincent Geloso states, “In 17 ridings provincially in Quebec, people under supply management are strong enough to change the outcome of the election.” Former federal Conservative cabinet member Maxime Bernier found this out the hard way. The vocal proponent of free markets was on-track to win the party’s leadership race in 2017 until running afoul of Quebec’s supply management fanatics, whose support is believed to have handed the leadership to Andrew Scheer. The debacle haunts the party to this day.

That brings us back to the upcoming USMCA negotiations. Under that trilateral agreement (successor to the previous North American Free Trade Agreement and, prior to that, the original Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1988), the U.S. gets less than 5 percent of Canada’s agricultural products market. Trump has been a longstanding critic of supply management, so this area is certain to be targeted in the upcoming trade talks. Canada is eager if not desperate to maintain or regain tariff- and quota-free access to the U.S. market for its hundreds of billions of dollars worth of annual exports; trading away agricultural supply management to secure that critical objective would make eminent sense.

The average family will need to spend $1,000 more on groceries in 2026 than this year. While other stupid government regulations like new labelling requirements for sodium content admittedly play a role in raising costs, supply management continues to be a major cause; without it, food prices in all the protected categories would actually fall.

Looking to pre-empt that risk, supply-managed farmer associations lobbied the federal government to pass pre-emptive legislation. On June 26, Bill C-202, making it illegal for any Canadian minister to reduce import tariffs or increase import quotas on supply-managed foods in future trade talks, was enacted by the Liberal government. Incredibly, even the Conservatives mostly voted for it. Whatever one might think of supply management or dairy quotas as such, a country formally signalling that its stance in international trade negotiations is entirely beholden to a tiny domestic lobby group is moronic. As Concordia University Economist Moshe Lander put it, “The government seems willing even to accept tariffs and damage to the Canadian economy rather than put dairy supply management on the table.”

This makes voters in those 17 Quebec ridings happy, but it’s certain to further rile Trump, causing needless friction in the lead-up to next year’s talks and kicking them off on an even more adversarial note. The Office of the United States Trade Representative has scheduled public consultations and a hearing on issues relating to the USMCA review. For all his bluster, Trump is a skillful dealmaker; he and his team surely see the Liberal government’s parochial antics as another source of Canadian weakness and another opportunity to gain advantage.

Meanwhile, Canadian food prices continue to zoom higher than the rate of inflation, with this report forecasting that the average family will need to spend $1,000 more on groceries in 2026 than this year. While other stupid government regulations like new labelling requirements for sodium content admittedly play a role in raising costs, supply management continues to be a major cause; without it, food prices in all the protected categories would actually fall. Trump has made it clear that ending Canadian agricultural supply management is one of his goals. Some speculate that Canada might not even get a new trade deal at all unless it surrenders supply management. If Trump succeeds in bringing that about, he’ll be doing Canadian consumers and entrepreneurial farmers a huge favour.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.