The universe is more like a great thought than a great machine.

—Sir James Jeans, The Mysterious Universe

At the beginning of all things, there must be not irrationality, but creative reason – not blind chance, but freedom.

—Pope Benedict XVI, Collège of Bernardins, Paris, 2008

Many years ago I was living on a remote Greek island and had rented a car from a dealership on the mainland. One day I noticed that one of the tires was flat, but the local garage was closed for the week and the only pump on the island belonged to Father Grigory. I managed to get in touch with him through the parish grapevine and after several hours he was at my door to administer the needed pneuma, the Greek word for wind, breath and sometimes air. (Pneu is French for tire.) It is also the Greek word for spirit, and it was being delivered by a man of God. As the tire was being inflated, it struck me that a mechanical contrivance was being maintained by a bearer of the spirit.

As we sat together to mark the occasion with a glass of ouzo – its own sort of spirit – I realized I had witnessed a kind of epiphany, a shower of what I somewhat facetiously call pnemes or “spiritual particles”, a grand unification of two realms, the earthly and the divine, the ordinary and the Other, one world guided or reinforced by one completely different. A bit over the top, perhaps, and yet quite accurate.

Science has its own version of the issue. Science and faith, cosmological inquiry and theological speculation, are central human compulsions and come together in thinking of the fundamental questions of life. An alloy of spiritual pleroma and cosmological fecundity, they cannot be separated without diluting both.

The Paradox of the Knot

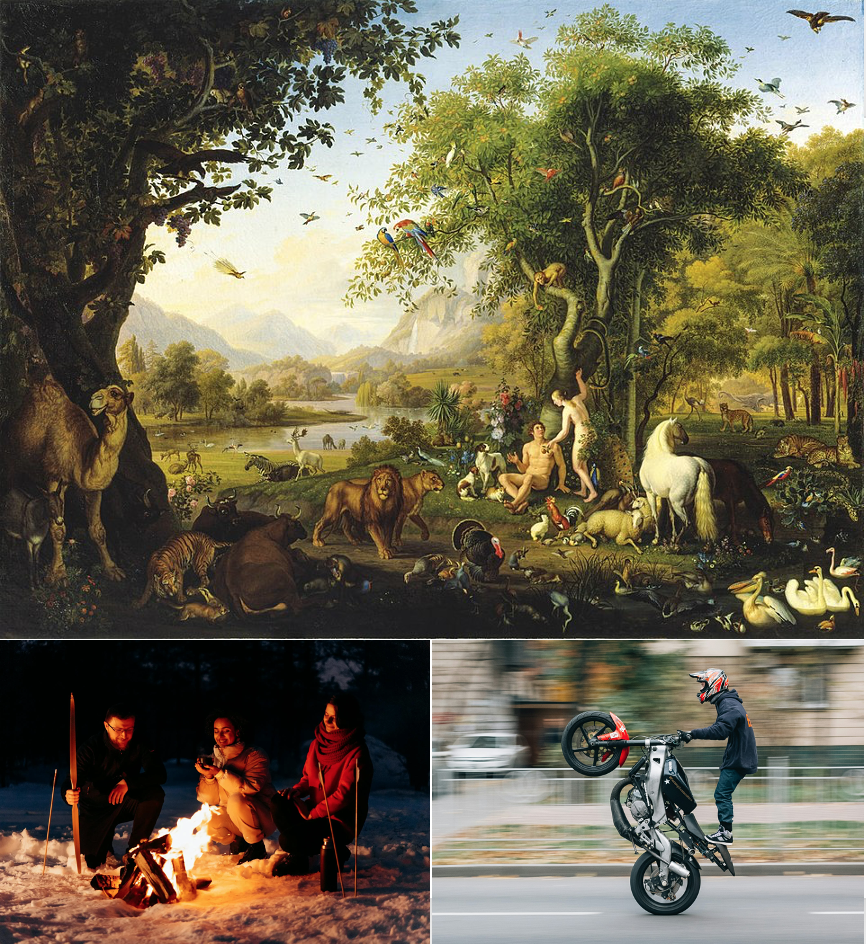

We can say that scientists and religious folk alike are people of faith espousing a deeply conservative set of convictions about the world in which they live; it is the core of their lives. The universe – or the Creation – itself is a fundamentally conservative structure. Intractable laws exist that must be understood and followed. The Garden of Eden is founded on the Word of God that must be obeyed if the conditions of existence are to be conserved, a moral prefiguration of the Ten Commandments. The physical universe is based on the laws of thermodynamics – the conservation of energy, the increase of entropy (disorder or uncertainty) over time, and a constant minimum value approaching absolute zero – as well as the expansion of space in which galaxies move away from a fixed point with a velocity proportional to their distance.

In the first case, disobedience is possible; in the second, not, at least in the objective realm we inhabit. Nonetheless, we are treating ineffably conservative entities, the empyreal politics of existence in time, space and the inexpressible. Both the Garden and the Cosmos are predicated on the foundational laws of conservation.

Science, like theology, has its own mysterious interconnections that are also aspects of arcane realities, often entailing jarring incompatibles. It addresses its own transcendent imponderables and material necessities, its sacred and mundane, its tangibles and incorporeals, its conviction of the existence of at least two orders of reality involving an apparatus of empirical investigation and a set of mathematical concepts that appear mystifying to the uninitiated. Experimental procedures are the link between abstruse theory and practical fact.

Scientists are also wedded to a set of personal beliefs that connect scientific pursuits to human endeavour. Their efforts to impose scientific clarity upon the hidden processes of nature and the narrow borders of the human intellect continue to animate them, though not always amiably. Emotional investments sometimes go too deep.

For example, theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss in A Universe from Nothing suggests that a universe can arise from “a boiling brew of virtual particles that pop in and out of existence” in the perfect vacuum of empty space, which is effectively Nothing. This implies the prior existence of empty space (or something called Nothing), whose origin is taken for granted within the continuum of time. The whack-a-mole particles it somehow contains just come and go in ways that cannot be predicted, which is the basis of what is called quantum reality, the micro-event horizon where objective reality ceases to exist. (These particles are “virtual” because they are essentially fleeting perturbations in a “field”.)

Scientific historian Stephen Meyer, a proponent of the theory of intelligent design, rebuts Krauss’ proposition in Signature in the Cell, asserting that “all attempts to simulate the origin of digital or genetic information have invariably involved the use of intelligence.” Information relies upon mind in order to be generated, arising from a dimension that is distinct from or precedes space and time as we know it. Meyer regards the organelles in the cell as God’s autograph. Astrobiologist Paul Davies is in full agreement. “There is no known law of physics,” writes Davies in The Demon in the Machine, “able to create information from nothing.” The basic difference in the controversy is that Krauss proposed a temporal vacuum as opposed to Meyer’s out-of-this-world noetic consciousness.

The two met in an acrimonious debate on the subject at Wycliffe College in Toronto in 2016. One can imagine Krauss’ eyes glazing over and Meyer coughing into his handkerchief. One recalls that scientific titans Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr wrangled over the status of quantum physics at the Solvay Conferences in Brussels in 1927 and 1930. Unlike the largely uncivil clash in Toronto, their exchange was fierce but congenial, culminating in a lifelong friendship.

In whatever way the universe was formed, it must have come to be in what we know as the four dimensions that were already present, three of space and one of time. There had to be something there for it to take root in.

Krauss and Meyer might have done better to sit together and share a glass of ouzo. In any case, the debate was marred by Krauss’ disparaging of Meyer and Meyer’s debilitating migraine which compromised his demeanour and to some extent his formulations. If God was in the audience, he left early. The episode puts me in mind of a passage from poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Journals: “From much, much more. From little, not much. And from nothing, nothing.”

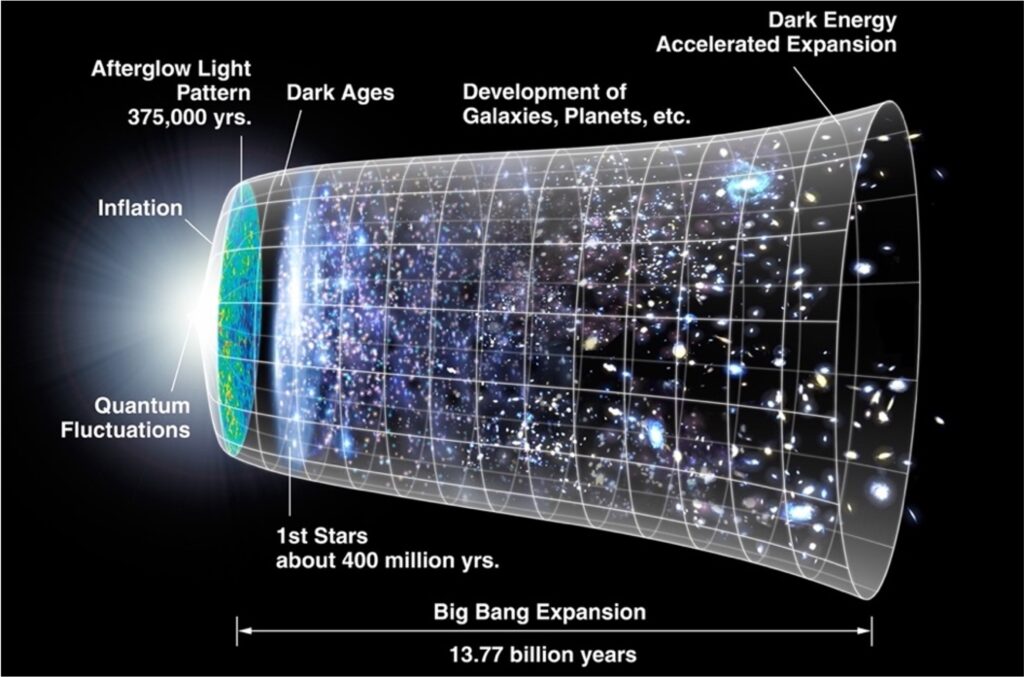

The issue clearly remains at the very core of cosmological inquiry, in particular with respect to space and time – the question of the auroral moment, or Big Bang. Our physical existence, writes astrophysicist Bernard Haisch in The Purpose-Guided Universe, “is so wrapped up in space and time that we cannot rationally imagine how something could exist and even be dynamic without starting its life in space and time.” In whatever way the universe was formed, it must have come to be in what we know as the four dimensions that were already present, three of space and one of time. There had to be something there for it to take root in, a blank canvas, a matrix of locations. Space and time are the conditions of existence for anything in the universe, as well as for the universe itself in both its physical process and its putative origin.

The dilemma is, according to the reigning scientific paradigm accounting for Creation, that the Big Bang created the universe with its full complement of laws, forces, matter, energy, space and time. The Big Bang is put forward as the source of everything, even space and time. Not a thing that we can conceive of existed prior to the Creative moment, not even the Nothing that spawns virtualities.

The question for Haisch pertains to the Big Bang’s explosive entry into whatever existed or didn’t exist before its self-manifestation as the evolving universe we live in. How can causation operate when there is no time or space to operate in? How can a universe emerge – which implies time and location – into Creation from an initial singularity that is neither in time nor space and yet actually created them?

How do proponents of Intelligent Design deal with the idea that the universe arose from a “vacuum” or “nothing”?

While some physicists propose that the universe could arise from a “boiling brew of virtual particles” within a vacuum, critics like Stephen Meyer argue that this still presupposes a spatial dimension and existing laws – which can also be described as forms of information. But, Meyer contends, all attempts to simulate the origin of complex information, such as genetic codes, invariably rely upon the use of intelligence. Indeed, all information relies upon some form of mind to be generated, a view supported by the fact that no law of physics identified to date is capable of creating information from nothing.

Eighteenth-century Swiss polymath Leonhard Euler believed existence and nonexistence could be mathematically correlated and devised an identity formula for nothing (i.e., nonexistence), considered the most beautiful of mathematical equations. It has the identities 1 and 0, it has the two most important transcendental numbers e and pi, and it has i for irrationals. It is: eiΠ=0. This is said to connect the realms of real numbers and imaginary numbers, bridging worlds. It’s a beguiling equation but baffling to those without mathematics, and it is experimentally unrealizable. Beauty is not always useful in the hunt for the evanescent.

In any “event”, whether the universe came into being during time, which as we will see makes no sense, or before time, which also makes no sense, the question continues to be asked in various and unsatisfactory ways.

Did the universe spring from a vacuum? Or did God put his supersensual artistry to work from some aesthetic proclivity? Was the universe the progeny of the Quantum Observer in whose image or “signal field” it is ostensibly disposed? Is the universe, as some believe, merely a hologram, a playful simulation whose deep structure is based on the sort of physics one would program into a computer, perhaps a prank cooked up by an interstellar super-race that obviously cannot be self-generated?

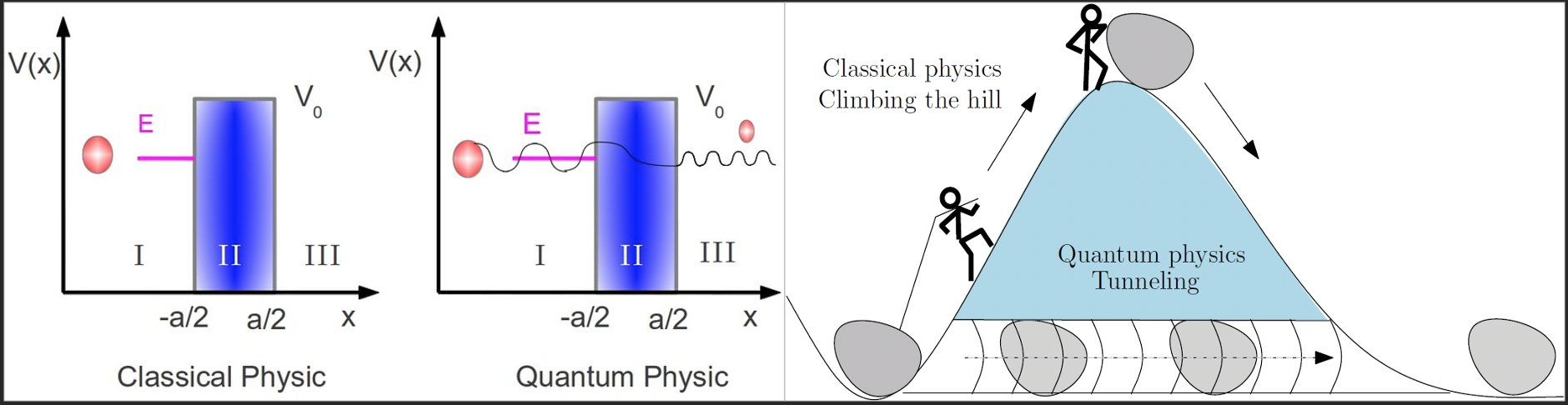

Even a prior event like quantum tunnelling that some cosmologists believe caused the Big Bang merely begs the question. The theory that the universe began on the other side of a black hole in another universe, or ignited in a collision between higher-dimension structures called branes as m-theory asserts, are similarly null. Note that each of these theories requires something; in none is the universe truly self-creating.

There is also the question of whether even the Big Bang is a convincing scientific theory. As Bjørn Ekeberg contended on the Scientific American’s blog some years ago, today’s multilayered theoretical edifice of the Big Bang may turn out to be inherently flawed, a confusing mix of fictional beasts invented to uphold the model. In his book Metaphysical Experiments, Ekeberg suggests that “scientific cosmology actually operates in a twilight zone between the physical and metaphysical,” a kind of theoretical squat. The Big Bang paradigm, he insists, does not describe known empirical phenomena but only maintains the mathematical coherence of the current explanatory framework, making it not a theory of Creation but merely an elaborate theory of itself. Many contemporary physicists agree.

Whatever our beliefs may be, the major issue stays in place, which leads to what we might call the paradox of the knot. Religious philosopher Søren Kierkegaard once wrote in his Journals, “To philosophize without dogma is like sewing without a knot at the end of the thread.” We have to start somewhere, with a new or accepted perspective or standpoint, some sort of “dogma”, where all that comes before the analysis we have embarked upon lingers in a state of obscurity. Everyone uses the knot but, as we’ve already seen, some would rather not acknowledge it.

If we adhere strictly to the thesis of the Big Bang, then the singularity creates time and space from a point outside time and space. It is an explosion of space-time, not an explosion in space-time, a thesis which does not launch.

Starting “somewhere” may simply be a matter of personal choice. The new problem that inevitably arises was proposed by deconstructionist Jacques Derrida in Of Grammatology when he observed that origins always recede into a prior time and space that is there to recede into. The origin is always a “trace”, something that is “absent present”, and its meaning is always indeterminate. The universe is granular; whatever occurs is always preceded by what we later disambiguate as a part of itself. Some morsel of “it” must have been there already for parturition to occur. Whatever has begun has, at least in part, begun earlier, and so on ad infinitum.

So, we choose a time or a place or a position in which to begin our quest. For those who believe that the universe was formed in a temporal field, it was always to some extent created before it was created thanks to the endless recess or, being empty, was plainly devoid of materials to shape into a cosmic substance in the first place. It had to be there for it to be there. At the same time, as it were, if we adhere strictly to the thesis of the Big Bang, then the singularity creates time and space from a point outside time and space. It is an explosion of space-time, not an explosion in space-time, a thesis which does not launch.

Reason for shared humility: The stories of Genesis and of the Big Bang both evade the ultimate question of origin, the one event which is impossible to revisit and which therefore remains fundamentally unexplained. Depicted: at top, God Creating the Earth, by Raffaello Sanzio Raphael, 1483-1520; at bottom, Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, by Jan Matejko, 1873.

Reason for shared humility: The stories of Genesis and of the Big Bang both evade the ultimate question of origin, the one event which is impossible to revisit and which therefore remains fundamentally unexplained. Depicted: at top, God Creating the Earth, by Raffaello Sanzio Raphael, 1483-1520; at bottom, Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, by Jan Matejko, 1873.The human imagination, however, cannot credibly conceive either alternative. Neither is persuasive, both are logically inadmissible. Science and religion are equivalent in this regard since both can only go back so far and no farther. The Book of Genesis can tell us nothing of what existed before the Lord created Heaven and Earth or about the background dark from which God divided the light.

The story of Genesis and the story of the Big Bang exhibit the same problem. There is no means of crossing the meridian of origins. There is no way of going back to what is before time, or even to the exact point of theoretical emergence in time – a trillionth of a trillionth of a second is the current estimate after time zero. The physicist and the votary are equally frustrated in their search for primal absolutes, and the subjects they deal with must remain fundamentally unexplained. There is no shattering surprise at the end of our search which is the beginning of the reason for the search, no butter-the-popcorn moment. God’s toolkit will never fully reveal itself. There is a reason for a shared humility.

The only thing we can be sure of is that the great occasion, the eruption of the universe, did not occur in anything like Henri Bergson’s la durée, or duration, expounded in his Creative Evolution as a “mental/spiritual life which overflows the cerebral/intellectual life” in the uniqueness of experienced time. In other words, the Creation itself cannot be palpably experienced, haptically imagined or directly felt, yet its passionate/mystic recognition can be intuited. It does not occur in our proprioceptive sense of time or “duration”, but in a weird recessive time, or an equally weird no-time, that we cannot envisage or apprehend, only assume to have uncannily been.

It seems exceedingly odd to say that God created the Universe at a specific moment some 13.79 billion years ago, as if he were operating on some sort of private schedule. It seems no less bizarre to conceive of the Universe coming into existence one way or another at a precise moment in time 13.79 billion years ago, not a tick before or after. Why that particular “date”? What’s special about that nano-second? When we think about this as sedulously as we can, it simply makes no sense whatsoever. Yet, here it is.

Hypotheses non fingo, said Newton of things that cannot be observed or experimentally studied, “I frame no hypotheses.” This is the horizon beyond which we cannot see. This is the knot. What came before we started to sew is not only cryptic and opaque, it is inconceivable. It is also impossible. It simply cannot have been.

Yet, untenably, the Creation did occur.

How does the “paradox of the knot” illustrate the logical difficulty in creating a convincing theory for the origin of the universe?

The “paradox of the knot” refers to the philosophical problem identified by the early-19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard that any cosmology must begin with a belief or dogma – a metaphorical “knot” like the one used in sewing – because otherwise the question of ultimate origin recedes infinitely into prior time and space. The Big Bang model exemplifies the paradox of the knot by proposing a universe self-created through an “initial singularity” that produced space and time. The theory harbours a logical contradiction: for the universe to emerge, it implies that a location and time already existed for it to occur in; yet the theory asserts that the initial singularity is the source of space and time, not an event occurring in space and time. Consequently, the human imagination cannot credibly conceive of a cause operating without the conditions of existence already present.

The Phantoms at the Centre

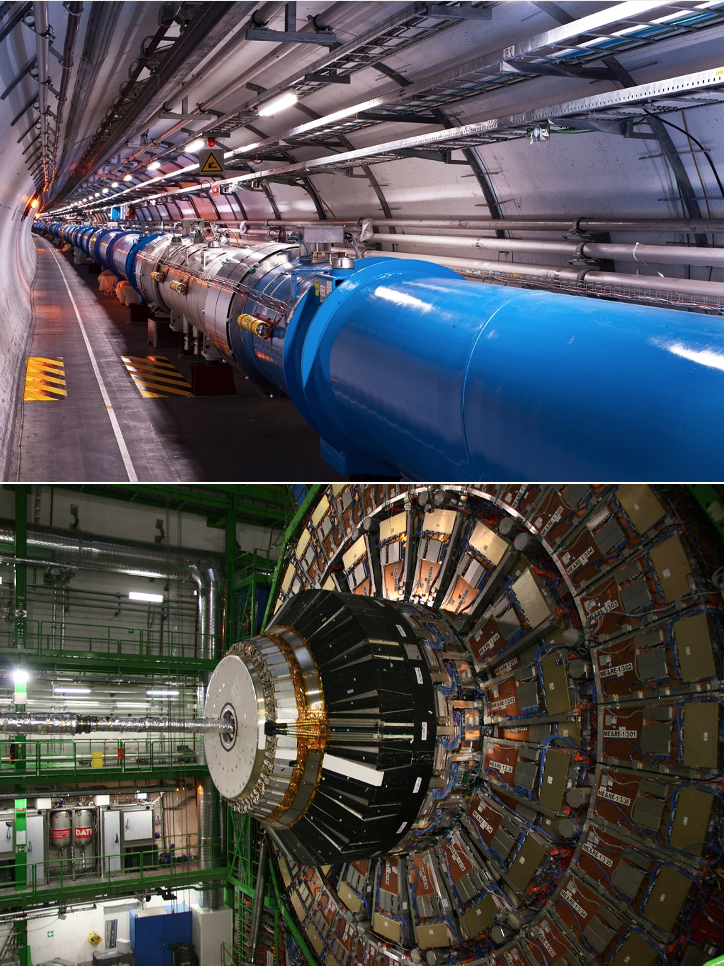

There is no observable or experimental way to resolve the riddle of how the temporal and spatial can arise from a previous temporal and spatial or from the non-temporal and non-spatial. Also troubling the scientific community is the more practical problem of how to mathematically unify the four fundamental forces of nature generated by (what may or not be) the Big Bang.

Scientists want to find a means to bind the strong force holding nuclei together, the weak force of atomic decay, electromagnetism, and gravity into a single set of laws characterized by elegance, parsimony, symmetry and universality. This would be the Grand Unified Theory (GUT) or, counting gravity which to date stubbornly remains mathematically isolated, the Theory of Everything (TOE), the Holy Grail of cosmology. But getting from the gut to the toe is, let us say, mathanatomically fugitive.

Few doubt any longer what Werner Heisenberg called ‘incommensurable quantities’ and Stephen J. Gould termed ‘non-overlapping magisterials’. These are now the order of the scientific day, describing two differing worlds, the latent and the manifest, that are clearly reciprocal but belong to different referential frames. These two conflicting architectures account for the world as a whole.

Scientists can merge electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force owing to the energies available in particle colliders. They are two aspects of a single, unified electroweak force, which existed “in the beginning” as one force, now evinced at different energy scales. There are also theoretical calculations to fold in the strong nuclear force at even higher energies. And all four forces are believed to be governed by “gauge symmetries” that allow for invariance of mathematical systems under conditions of change, and permit a descriptive reunification of the forces into the single larger group. But gravity relates to the structure of spacetime itself rather than “living” in spacetime and, thus far, gravity refuses to join the party that speaks to the organization of the grand structure.

As if this were not enough to unsettle the mind, at the quantum level new issues intervene. What is referred to as Laplace’s Demon, asserting the deterministic mechanism of the classical manifold, has been banished in favour of probability, the basic feature of complex, infinitesimal structures. There may be no final word on the Big Bang commanding 100 percent agreement, but few doubt that quantum physics obeys a wholly new and different set of rules from those in the large-scale world of everyday human experience.

Few doubt any longer what Werner Heisenberg called “incommensurable quantities” and Stephen J. Gould termed “non-overlapping magisterials”. These are now the order of the scientific day, describing two differing worlds, the latent and the manifest, that are clearly reciprocal but at the same time belong to different referential frames. Though lawfully dissimilar, these two conflicting architectures account for the world as a whole. The objective forms at the periphery where we live are merely the outward expressions of the phantom-like hidden forms at the centre that we know only indirectly. Our home is the product of mismatched sets of physical law, a fact which is both theoretically and empirically incredible.

How does this contradiction play itself out? Local realism is what ensures that objects must possess pre-existing values abiding by the laws of classical physics prior to any measurement, that is, laws which scaffold the world of our ordinary, technically predictable reality all the way from the atom to the galaxy. Thus, in the classical milieu, the object is there at a discernible position and at a given, specifiable time. That is why we can confidently book a reservation at a restaurant that remains at a fixed address at any given time instead of it migrating from one street to another at any other hour of the day.

Non-local events, however, are categorically different. In the quantum milieu, the object fluctuates in a cloud of probabilities called a wave function which collapses only with observation, allowing the “particle”, which did not exist in a particular time or position prior to the observation or measurement, to suddenly appear. Were we living in the quantum field, we might as well give up planning for a meal out since we could neither pre-arrange for a time nor have any idea where the restaurant would be when we left the house. It would not appear at all unless we correctly guessed its location and went there to “make a measurement”, as the physicists like to say.

The statistical equation for the wave function of the probability of finding a particle in a specific region, also known as the Born Rule, looks like this in its compressed variant: |Ψ(x,t)|2. The wave function is not directly observable but its magnitude squared gives a real, positive number, another way of saying that it is both problematic and real. In the quantum state, then, the “particle” is the probability wave we cannot surf with confidence. But in the scale of our existence it is a phone number, a restaurant and an exquisite fettuccine alfredo at La Piazza Dario.

A famous thought-experiment tackles the subject. Erwin Schrödinger’s cat is neither alive nor dead, or is both, until the intermittently radioactive box in which it lies is opened and the feline is either mourned or fed. (The joke among physicists is that the experiment was proposed by Schrödinger’s dog.) One interpretation of the groundbreaking Austrian physicist’s thought-experiment states that the instant at which the radioactive atom in the box decays, presuming it does, occurs only after the event has been monitored. In quantum physics, a measurement’s results can send information back in time, that is, a present measurement setting in “delayed choice” experiments can retrocausally influence an earlier, unobserved measurement. Strange, but so.

Another reading proposes that since radioactive decay is a quantum event, the radioactive atom exists in wave-superposition and is both decayed and not decayed simultaneously, so the cat winds up both alive and dead until the box is opened, the wave function collapses, and one or the other result occurs. Mutatis mutandis, it’s a bit like proposing that Lazarus in the cave is both alive and dead until Christ bids him come forth and thus collapses the wave function. Thankfully, this was not a quantum experiment using photomultiplier detectors.

Incidentally, the thought-experiment expressed Schrödinger’s view that wave mechanics were being ridiculously misinterpreted. Yet it proved immensely fruitful. One of Schrödinger’s kittens was the “many-worlds” theory, inasmuch as the quantum solution suggested the existence of parallel worlds to account for each possibility. Yogi Berra also knew his quantum: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

Two worlds, two outcomes? Erwin Schrödinger’s (left) cat, a famous thought experiment, illuminated the apparent absurdity of quantum physics by applying it to the regular world. A hypothetical cat in Schrödinger’s box exists in two states, being neither alive nor dead, along with a vial of poison that might be shattered by a radioactive substance that is both decayed and not decayed – until the box is opened and the outcome is observed. (Sources: (left photo) American Institute of Physics; (right image) Dhatfield, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Two worlds, two outcomes? Erwin Schrödinger’s (left) cat, a famous thought experiment, illuminated the apparent absurdity of quantum physics by applying it to the regular world. A hypothetical cat in Schrödinger’s box exists in two states, being neither alive nor dead, along with a vial of poison that might be shattered by a radioactive substance that is both decayed and not decayed – until the box is opened and the outcome is observed. (Sources: (left photo) American Institute of Physics; (right image) Dhatfield, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)Adam Becker in What Is Real? sympathetically mentions Nobel Laureate Sir Anthony Leggett’s confession to being a kind of scientific werewolf, solving equations by day and prowling through the quantum forest at night, hunting for blood, doubting whether quantum can really be extrapolated to the macroscopic level. For Leggett, quantum paradoxes are both risible and irritating, though he continues to grapple with them.

Paradox or no, the tibia of quantum physics is that the “particle” to be detected is actually a spread-out field of probabilities and only our observation makes one of them true, like the fate of the poor pussy or Leggett’s now exsanguinated victim. It then becomes a verifiable result in our objective sphere. The question is how these two discrete and discrepant realities at both the quantum and macroscopic planes run happily beside one another, how two divergent and even conflicting sets of laws combine to create a unified and coherent world.

What is “decoherence” and why is it considered scientifically problematic?

“Decoherence” is the mysterious transition mechanism that connects the probabilistic, rule-bending quantum world to the stable, predictable world following the laws of classical physics that humans experience. In the quantum realm, for example, “virtual particles” can violate physical laws, such as borrowing excess energy from the universe, provided the virtuals disappear almost instantly. Another seeming absurdity is quantum entanglement, in which a quantum particle in one location instantaneously influences the behaviour of another particle that may be light-years away. The world of classical physics, by contrast, relies on fixed values and locations. Some describe decoherence as akin to “sorcery” because it purports to explain how these two clashing and dissimilar palettes somehow coalesce into an orderly reality, a process that theoretically should not be possible.

What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?

The phenomenon known as “decoherence” serves as the gantry or transition between the zany, probabilistic behaviour of the quantum world and the stable, predictable reality we experience every day. We are at the mercy of the physical laws but in the quantum world physical laws may be violated with short-term impunity. Gavin Hesketh points out in The Particle Zoo that “virtual particles don’t even have to obey the laws of physics, but can bend the rules” to gain excess energy from the total universal quantity to sustain a flickering existence of 10-43 seconds before shuffling off the mortal coil. It is as if, unnoticed, they steal a Mars Bar for energy from the universal candy counter but are then compelled to give it back pronto with only a bite taken out of it. The bar is then magically restored. There is sorcery at the bottom of things.

When a quark/lepton ‘spins’, its fellow quark/lepton will reverse ‘spin’ even if it’s at the opposite end of the universe, the required information transmitted instantly.

The quantum world is pretty funky, reminiscent in a way of the gothic horror comedy Beetlejuice, as if quantum emanated either from the film or the film’s name-origin, the star Betelgeuse in the Orion Constellation. On the contrary, from the perspective of experience, our world is comparatively rudimentary. Decoherence is unexplainable; the “operation” should not be possible, and many physicists think it is not. But the impossible seems to be a basic law of subatomic physics. Zero-point energy, which is the latent or underlying sea of energy due to quantum oscillations that presumably generate reality from indiscernible probabilities, is presumably the Tao – the fundamental principle – or maybe the quick of the routine and calculable billiard-ball world we live in.

To return. If the first puzzle is how something can actually begin when there is no space or time for it to begin in or no earlier space and time which itself would have had to begin, the second conundrum is how two dissimilar and even clashing palettes of law can paint an integrated and orderly field of predictable activity and coalesce into what amounts to a habitable world via the principle of decoherence.

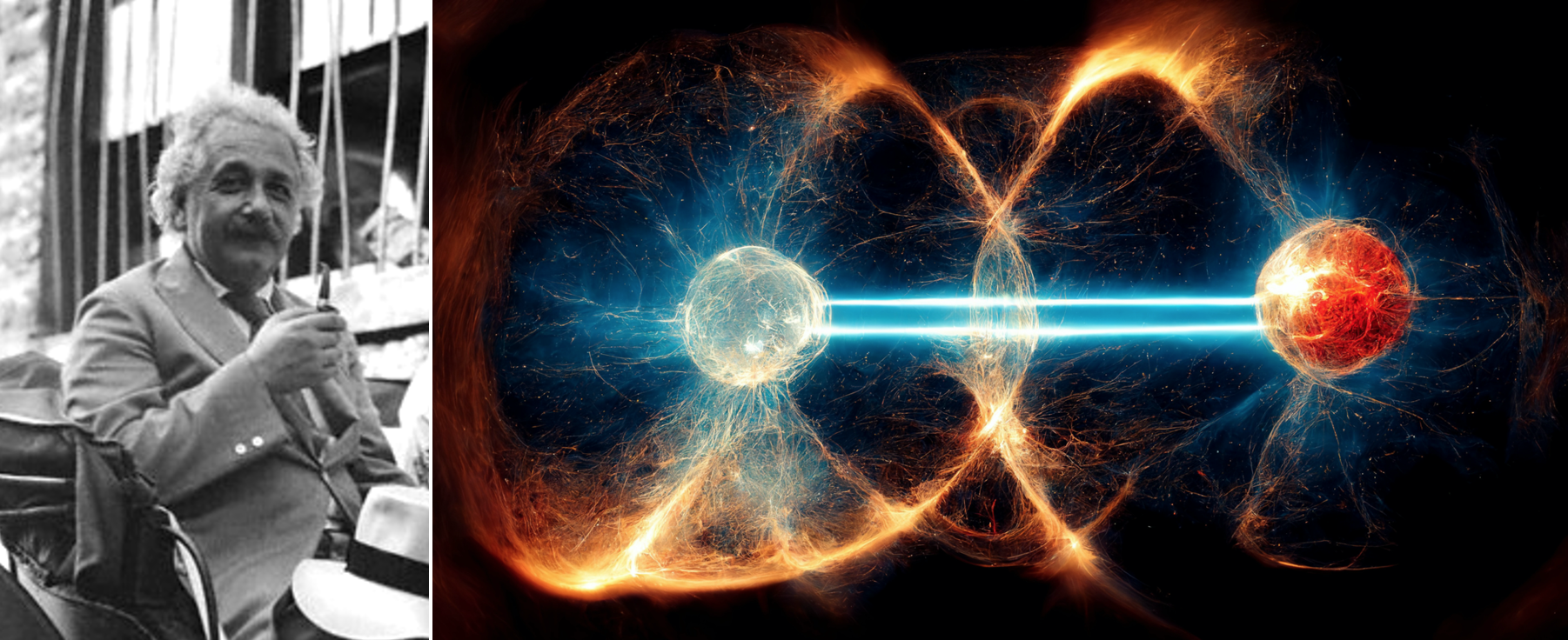

Add to these two a third, what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance”, or quantum entanglement. He was referring to the building-block particles with no internal structure called quarks and leptons that are linked or correlated in a way that is faster than the boundary speed of light. When a quark/lepton “spins”, its fellow quark/lepton will reverse “spin” even if it’s at the opposite end of the universe, the required information transmitted instantly.

I believe it is licit to define these transformations as involving a spiritual level of reality. It’s what Brian Clegg has concisely called The God Effect in a book I consider indispensable. A universal intelligence appears to interact with humanity in a range of contact previously unanticipated. One might even say that the universe comes into existence because God observes it. But there is another problem here: observes what? Where is the cloud of probabilities that exists apart from the Supreme Being? There can be no probability, no hierarchy of ancillary realities that boasts an independent existence, zooming in at a tangent. Some cosmologists throw up their hands and believe that the universe is God’s dream and we are stuck in its quicksand until the great awakening releases us.

We now have the three major physical challenges that baffle the human imagination, the trinity of subliminal but absolutely central scientific problems: origins, decoherence and entanglement. No descriptive equation, no array of calculations, can account for the three aspects of our cosmological cliffhanger. They point to the inscrutable or occult mystery of existence as well as to the noble pixilation of the hunt for knowledge.

Recognizing the immanence of spirit in the world of mass and energy is not a pathology of reason, but a sign of the open mind a scientist must bring to the world of his professional interest, signifying the innate human desire to know the truth of the transcendent.

As I have argued as an underpinning premise throughout, the problem is not only scientific but theological. Physicist Menas Kafatos, author of The Non-local Universe: The New Physics and Matters of the Mind, proposes the “triadic system”, a model integrating the relationships between epistemic consciousness, the objective universe and the subjective individual. Kafatos’ system functions in the quantum area and migrates up to biological processes and the nature of the cosmos. The model applies across the board and influences the exploration of reality, that is, of ultimate things, in both the physical and spiritual realms. Kafatos makes a strong case that the poles of science and religion are not opposites but complementary.

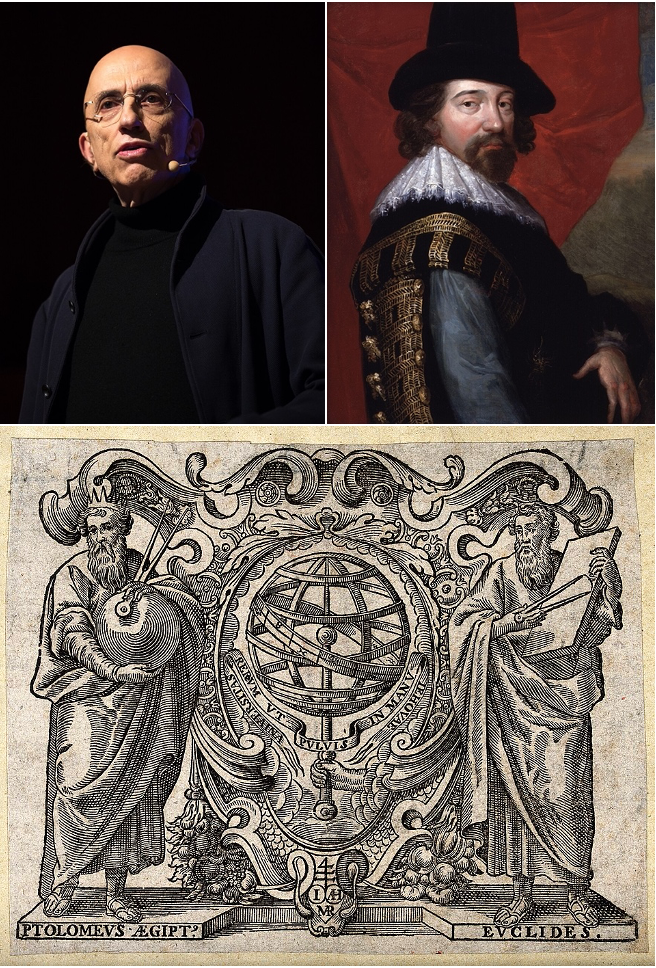

This is not a new proposition. In 1620 Francis Bacon’s Novum Organon stressed that humans’ rights over nature were “assigned to them by the gift of God,” enabling our investigations and discoveries. There was no radical lesion between reason and faith. God belonged to no official communion, logical systems were not subject to theological warrant, skeptical reason and the inductive method were essential to learning, and wisdom regarded final things. Authentic faith and rigid orthodoxy, however, were two different qualities. Bacon insisted that the intellectual faculty must be “governed by right reason and true religion” acting together. And that what cannot be known is common to both.

Recognizing the immanence of spirit in the world of mass and energy is not a pathology of reason, but a sign of the open mind a scientist must bring to the world of his professional interest, signifying the innate human desire to know the truth of the transcendent, so far as this is possible. A passage from the Second Vatican Council’s Dignitatis Humanae of 1965 makes the quest for knowledge a human, almost a religious responsibility: humans possess reason and free will which obligates them to seek the truth about the final causes of the universe.

All this reminds me of early Christian theologian Tertullian’s pivotal question, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” The question is with us still, and may be answered insightfully and without hesitation: Everything. I would submit that God is not virtual. God is not a mere probability. God does not need to file a patent for an invention no one really understands. God is no more improbable than the neutrino, also known as the “ghost particle ghost”, so small it can pass through everything and whose signature typically manifests as deviations in the outgoing lepton flux or energy spectrum.

Even so, what comes before God is the waking child’s unanswerable question. What could have existed beyond the mind-numbing veil? So we are back where we both started and ended. But the mystery is here and we have been put to the test. The pilgrimage of the human mind will continue despite the inevitability of ultimate failure, as seems to be ordained, certainly on this side of the zodiac. It’s part of the business of living and thinking, part of the larger game. Consider Victorian poet Robert Browning’s lines in “Andrea del Sarto”:

Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what’s a Heaven for?

And 17th Century metaphysical poet and Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral John Donne, who wrote in his poem “To the Countess of Bedford”:

Reason is our soul’s left hand, faith her right,

By these we reach divinity…

Perhaps reason can arrive at non-empirical truths or, if this is not feasible, at least validly raise non-empirical questions. Scientific analysis and religious belief, quantum and faith, the original singularity and the spiritual order, the particle and the pneme, are equally mysterious. And they are cordially sipping a tumbler of ouzo together.

End of Part I. Part II will be published in early January as C2C’s first new essay of 2026.

David Solway’s latest prose book is Profoundly Superficial (New English Review Press, 2025). His translation of Dov Ben Zamir’s collected poetry New Bottles, Old Wine (Little Nightingale Press) will be released in the new year. Solway has produced two CDs of original songs: Blood Guitar and Other Tales (2014) and Partial to Cain (2019) on which he is accompanied by his pianist wife Janice Fiamengo. A third CD, The Dark, is in planning.

Source of main image: Unsplash.