The United States isn’t the only place where it takes longer and longer to count the vote. Two weeks to the day after British Columbians went to the polls, voting officers were finally allowed to tally the 662,000 ballots that had been returned by mail – an astonishing one-third of the votes cast. The mail-in ballots, however, only confirmed what pre-election polls and previously-counted ballots had shown: an “Orange Wave” for the incumbent New Democratic Party.

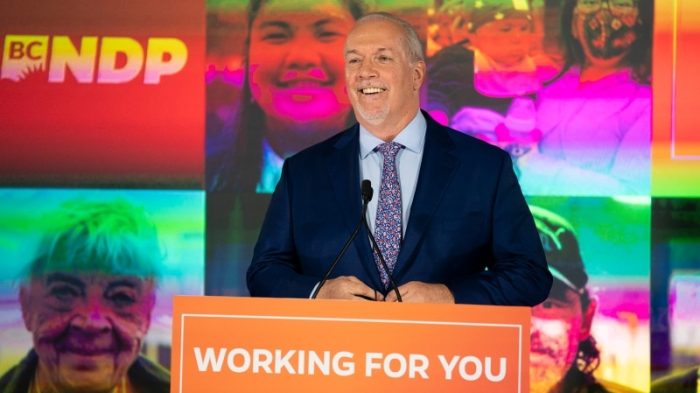

This was a history-making event, for while the NDP has held power on three previous occasions, this was the first time the party was re-elected out of a precarious minority government position into a solid majority (it also won re-election in the 90s). Under leader John Horgan, the NDP won a lower percentage of the popular vote (47.7) than Donald Trump, yet was handsomely rewarded with 57 of the province’s 87 seats. The Liberal Party was reduced to 28 seats, a net loss of 15, and the Green Party lost one of its previous three seats while getting 15 percent of the popular vote.

Explaining B.C. provincial politics to friends and family scattered across Canada is always challenging. The so-called Liberals are a broad tent that in addition to actual liberals houses milquetoast free-enterprisers, conservatives and even elderly holdovers from the old Social Credit Party. During the campaign, Liberal MLA Laurie Throness from the semi-rural and somewhat religiously-inclined riding of Chilliwack-Kent was turfed after an off-the-cuff remark at an all-candidates meeting, where he called the NDP government’s proposed free birth control policy “the old eugenics thing where…poor people should not have babies.” The 62-year-old Throness, who holds a Ph.D. from Cambridge University, half-apologized on his Facebook page while defending “freedom of speech and religion.” But that and his ouster were not enough, and the debacle gave the NDP the gift of a seat it had never dreamed of taking.

The provincial NDP’s fortunes have waxed and waned since Dave Barrett led the “socialists at the gates” into office for a brief period from 1972 to 1975. The party was also in power for most of the 90s under Mike Harcourt and Glen Clark. Then came a long period of Liberal government that included the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. Despite riding a largely foreign-funded post-Olympics real estate boom, the Liberals under Premier Christy Clark (no relation) in 2017 felt the sting of increasingly disillusioned voters intent on “throwing the bums out, all of them.”

The Liberals actually bested the NDP in the 2017 election, 43 seats to 41, but the B.C. Green Party was able to leverage its 17 percent popular vote share, with only three MLAs, into holding the balance of power. And that allowed the then-58-year-old Horgan to form a government and become premier. The Victoria native, former pulp mill worker and Keg Steakhouse waiter, who also holds an MA in history, had represented the Greater Victoria constituency of Langford-Juan de Fuca since 2005, becoming NDP leader in 2014.

B.C.’s next election was not due until autumn 2021, and in the days before kids returned to school this September, it seemed ludicrous even to consider a snap provincial election during a public health emergency. But thanks in good measure to the calm demeanour of sainted Covid-19 heroine Bonnie Henry, B.C.’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, ably assisted in her daily briefings by Health Minister Adrian Dix, Horgan and his party were offered a veritable political gift box: record popularity in the polls, a greenhorn Green Party leader in Sonia Furstenau, and a Liberal Party with the most uncharismatic leader since the NDP’s Bob Skelly.

Though sometimes ham-handed and overbearing, Horgan boasts sharp political instincts and a combative style more in line with the party’s union history than the ivory towers. As he saw it, he could stick with B.C.’s four-year election cycle and hang onto power for another year – but then risk losing the election running against an energized Green Party and the Liberals under a new leader. Or he could campaign amidst a pandemic, with all the risks that entailed – but against an opposition in disarray.

Horgan chose the latter. British Columbians were off to the polls after a short four-week campaign in which few solid issues emerged. Neoliberal policy experts were no doubt shocked to see Wilkinson wage the entire campaign without once mentioning a “balanced budget” – although he did remember to remind viewers who tuned into an all-candidates debate that “I am a doctor” no fewer than three times, presumably to prove his bona fides on healthcare. It was subsequently revealed that Wilkinson had resigned from B.C.’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in 2013. The overachieving Wilkinson (he won a Rhodes scholarship while attending medical school at the University of Alberta) is also a practising lawyer who once defended tobacco giant Phillip Morris against a provincial government lawsuit.

Wilkinson’s best line probably came when he declared, “It is not acceptable to hear of people being chased down the street by a man with a chainsaw.” There’s nothing quite like living up close and personal to mental illness, chronic poverty, open-air drug use and overt violence.

What was dubbed “Lotus Land” decades ago has deteriorated into something darker and, in a few instances, almost dystopian, especially in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side. Wilkinson’s promise to dismantle homeless tent cities in Vancouver and Victoria addressed a vexing problem that became far worse over the summer when the City of Vancouver relocated hundreds of homeless camped in Oppenheimer Park several blocks east to Strathcona Park. Katie Lewis, a freelance journalist and vice-president of the Strathcona Residents Association, wrote poignantly about the camp’s incursion into her gentrifying neighbourhood for The Line. “This seems like a story without a happy ending,” she concluded. “So we wait.”

On her way back home after running soup to a friend’s house nearby, Lewis was assaulted near the edge of the park by a stranger brandishing a metal pipe. This wasn’t the only violent incident; Wilkinson’s best line of the campaign probably came when he declared, “It is not acceptable to hear of people being chased down the street by a man with a chainsaw.” There’s nothing quite like living up close and personal to mental illness, chronic poverty, open-air drug use and overt violence to change your thinking on social engineering. Still, the NDP can be expected to continue throwing hundreds of millions of dollars at the problem and the money will vanish, similar to when the U.S. government built massive urban housing projects.

Wilkinson and especially Furstenau never had a chance. In a province where elementary and high school students were just a year earlier given the day off to attend climate-change rallies, the single-issue Greens were pushed off the front pages by Covid-19. During the only televised leaders’ debate, held halfway through the campaign, Furstenau’s only real line of attack was that the NDP had broken its power-sharing deal with the Greens. That’s politics.

The Liberal defeat wasn’t all Wilkinson’s fault. The brand has been deteriorating for years. Today it’s a party of tired ideas stained in public memory by massively supporting Chinese investment – to the detriment of Canadian homeowners. The party’s predilection to tolerate money laundering, numbered companies, illegal immigration and students owning mansions had built a slow but powerful wave of resentment that crashed upon the Clark Liberals last time around. It was no longer an overt election issue this time, but the stench seemed to linger, even in Richmond’s fertile ethnic soil. As for the Greens, weirdly they increased their popular vote while losing influence.

With his delivery of the Orange Crush, Horgan is now master of B.C.’s political landscape, needing Green minority support as much as a ski resort needs global warming. But one might well ask, without a trace of facetiousness: who would want such a job at this time? Sitting as a Member of the Legislative Assembly over in Victoria (or posing as one on Zoom) seems like the very last paying gig one could ask for, unemployment be damned.

Despite some economic “green shoots”, there are threats galore. Jammed between the intensifying geopolitical, cultural and trade war with the Chinese and a surely protectionist American Congress, B.C.’s exports are highly vulnerable. Those in the public and quasi-public sectors still have well-paying and relatively secure jobs with defined-benefit pensions. To keep the engine running, there will be massive pressure to deliver unfathomably expensive projects like 100 percent government-funded seniors’ housing, a new LEED Platinum school for False Creek and high-tech healthcare solutions – to say nothing of extending the Vancouver Skytrain in several new directions, replacing the George Massey Tunnel, completing the white-elephant Site C Dam on the Peace River in the province’s northeast, and putting out the tire fire at the Insurance Corporation of B.C. There’s little public animus against any of these.

B.C.’s long-term meteorological forecast is for higher-than-average wind and rain, and the new majority NDP government will also face a figuratively stormy winter. Sure, the Bank of Canada is printing money as quickly as it can to backstop the torrent of federal and provincial spending aimed at keeping us all, um, afloat – if not sane. But as federal government and corporate wage subsidies come to an end, the Pacific Coast’s receding tide of jobs and companies will smell worse than funky seaweed at low slack. Not even a kayak will be able to negotiate the shoals and avoid the briny deaths still to come. Speaking of seafaring craft, B.C.’s tourism industry has essentially foundered. Now that virtually nobody can get here, what do you think might happen? The downdraft will demolish not only some of the heli-skiing companies for the world’s ultra-rich but untold thousands of mom-and-pop restaurants, souvenir shops, kayak rentals and guide-outfitters. One can hardly imagine their fear and grief right now.

Once he lost the Trans Mountain Pipeline fight in court and realized he didn’t need the Green Party to survive, Horgan managed to “move on”. This suggests we are dealing with a highly skilled politician who is more pragmatic and less ideological than our Liberal prime minister.

Possibly for these very reasons, while there are plenty of grumpy people in B.C., political polarization amidst the pandemic is not as bad as in those Solidarity times when “fry spotted owls in oil” forest-workers’ unions clashed with Social Credit used-car salesmen and Birkenstock-wearing SFU “Communications” grads. If anything, the pandemic actually soothed some of B.C.’s historically deep divisions – free enterprise/redneck farmer versus Marxist professor/union leader – that for decades has marred political relations and discourse here. Private-sector union members are scarcer than restaurants and retail outlets on Robson Street and even the most ardent natural resource executive doesn’t fear expropriation or nationalization.

Repairing the near-destruction of the “Best Place on Earth’s” tourism industry will be very hard, but there’s promise amidst increasing Indigenous support for

certain industrial projects like LNG.

Horgan, indeed, can be expected to support the mega-projects that will create high-paying jobs for itinerant tradespeople as well as, for the first time, fully-invested First Nations. This especially includes the Coastal GasLink pipeline that is to move the natural gas which is critical to B.C.’s budding LNG export industry. Horgan seems set to borrow and spend while preserving or even strengthening B.C.’s key wealth-producing industries.

If this seems rather improbable, remember this is a man who manoeuvred himself and his party away from opposing the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, after fighting it tooth and claw in court, and seeming to base much of his political future on it. But, once he lost in court and realized he didn’t need the Green Party to survive, Horgan managed to “move on”. This suggests we are dealing with a highly-skilled politician who is more pragmatic and less ideological than our Liberal prime minister.

The 2020 election could prove entirely unlike the NDP’s flash-in-the-pan performance in the early 70s, instead redrawing B.C.’s electoral map for up to a generation. Today’s NDP has a whip-smart rising star named Bowinn Ma in North Vancouver-Lonsdale. The professional engineer and millennial is already being touted as a natural successor to Horgan, in part because of the hope she could siphon off a good portion of the Green Party’s vote.

Given the fact that B.C.’s median family income is $79,000 and the average single-family house price is $738,000, home ownership in the laid-back West Coast is a shockingly high 70 percent. Unlike those CERB-addicted Albertans, British Columbians simply stop in at their local ATM to order an increase to their home equity line of credit (at 0.5 percent or “historically low” mortgage rates) and Wham!, it’s off to the Tesla dealership for a new set of socially conscious wheels. Back in 2010, commemorative licence plates hammered out for the Winter Olympics bore the cringeworthy slogan “The Best Place on Earth.” A week after this year’s election, local boosters announced their intentions to bid for the 2030 Winter Olympics. Until the pandemic ends, you’ll just have to take our word for it.

Steven Threndyle is a North Vancouver-based freelance writer and communications specialist.