In 2015, then MP Justin Trudeau sat down in a park with CBC heavyweight Peter Mansbridge for a primetime interview in the lead-up to the next federal election. Sitting on a folding chair in the shade, candidate Trudeau spoke about his vision for Canada and about his father’s legacy. One comment stood out at the time, but may since have been forgotten. To Mansbridge’s seeming bemusement, Justin Trudeau remarked that it was “well understood” that the centralizing of control within the Prime Minister’s Office began with his father, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. As his son, Justin said he “like[d] the symmetry” of being the one to end that.

There certainly has been a kind of symmetry between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his father. But it’s not the sunny symmetry the current PM spoke of so hopefully seven years ago. It played out in his government’s crackdown on the 2022 Freedom Convoy – the forceful clearing of the protesters, the organizers arrested and held without bail – and in his invocation of the Emergencies Act, which allowed the freezing of bank accounts, the creation of a new law prohibiting certain public gatherings and, frankly, anything else the federal Cabinet deemed necessary.

It’s the darker symmetry of repetition from father to son: heavy-handed government over-reach with the use of force, civil rights abuse under the guise of a crisis, relying on the extraordinary powers of emergency legislation, and then relying on secrecy to prevent oversight. It begins with Pierre Trudeau’s invocation of the War Measures Act and is made manifest with Justin Trudeau’s invocation of the Emergencies Act more than 50 years later.

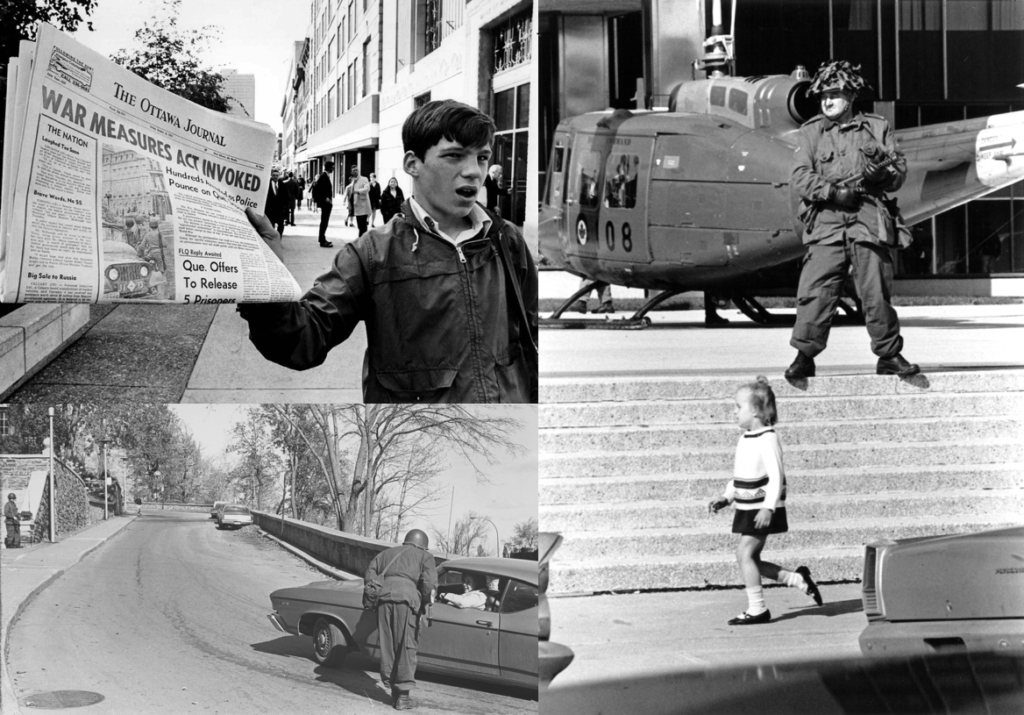

The main difference is that when Trudeau Senior invoked the War Measures Act in 1970, Canada was truly faced with a crisis. There had been nearly a decade of terrorist bombings by the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), and the group had already murdered at least eight people. On October 5, 1970, the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross from his posh home in Montreal. Five days later, the separatist group kidnapped Quebec’s deputy premier Pierre Laporte from his front yard while he was playing with his children. It was the last time his family saw him alive. His body was found in the trunk of a car at an airport parking lot on October 17. This series of events became known as the October Crisis.

The crisis was certainly real, but even so the War Measures Act was too extreme. The law suspended basic civil rights and liberties. It allowed police searches and arrests without warrants, and prolonged detention without charge or the right to see a lawyer. Further, Canada’s army was called out and deployed in the streets in aid of law enforcement, creating an aura of martial law. While the War Measures Act was short of martial law, Prime Minister Trudeau Senior famously dismissed the objections of civil libertarians in an interview with the CBC. Asked about concerns over the military presence, he retorted that “there are a lot of bleeding hearts around that just don’t like to see people with helmets and guns, all I can say is go on and bleed. But it’s more important to keep law and order in society than worry about weak kneed people who don’t like the looks of a soldier.”

A few hours after the War Measures Act came into effect, almost 500 Quebecers were arrested and as many as 10,000 would be subjected to searches without warrants. Police officials abused their powers, and some prominent artists and intellectuals associated with the Quebec sovereignty movement were detained. For example, police arrested Quebec singer Pauline Julien and her journalist partner Gérald Godin. “Why was I in jail?” asked Godin. “If only they had questioned me, I might have had an inkling. What had I said? What had I written or published?” Julien and Godin were held for eight days, then released without charges. In the end, only 62 people were charged and of those, 32 were not granted bail.

The replacement of the War Measures Act is the Emergencies Act. Passed in 1988, it is intended to rein in the extraordinary powers that were abused when Trudeau Senior invoked the previous legislation. The Emergencies Act defines the kinds of security situations that can trigger it.

Following the October Crisis, the RCMP was widely criticized for its conduct. But it also came under fire for having failed to act earlier on intelligence. The RCMP Security Service responded with an escalation of its activities, beginning a pattern of illegal acts that included unauthorized “sting” operations, illegal break-ins, and the theft of 14 cases of explosives from a construction site in 1972. The RCMP even burned down a barn they suspected was to be used by the FLQ and the Black Panthers, a violent U.S. Black liberation group. The crackdown was part of an attempt to prevent separatist terrorism in the lead-up to and during the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal.

The War Measures Act, invoked in 1970 during the October Crisis, suspended basic civil rights and liberties, putting troops in the streets and allowing police searches and arrests without warrants; the crisis was real, but the response excessive. (Sources of photos: (top left) The Canadian Press/ Peter Bregg, (bottom left) The Canadian Press/ GF, (right) Library and Archives Canada/PA-117477)

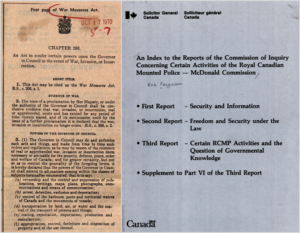

In 1977, a Royal Commission was struck to investigate the extent of RCMP wrongdoing in the wake of the October Crisis. Led by Judge David Cargill McDonald, it delivered a report in 1981 entitled Freedom and Security Under Law that called for major revisions to the War Measures Act. This led ultimately to the law’s repeal and the dissolution of the RCMP’s domestic intelligence branch.

The replacement of the War Measures Act is the Emergencies Act. Passed in 1988, it is intended to rein in the extraordinary powers that were abused when Trudeau Senior invoked the previous legislation. The Emergencies Act defines the kinds of security situations that can trigger it, and government actions under the Act are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This makes the subsequent abuse of the Emergencies Act by Trudeau Junior during the Freedom Convoy protests a profound historical parallel – and all the more outrageous given the lessons of the past.

Beginning on January 22, 2022, thousands of vehicles formed convoys from several points across Canada and hundreds of them converged in Ottawa on January 29 with a large-scale protest at Parliament Hill. The Freedom Convoy’s initial purpose was to protest Trudeau’s newly imposed vaccine mandate for truck drivers that required them to show proof of Covid-19 vaccination to cross the Canada-U.S. border. It ended up drawing thousands of other Canadians to Ottawa who harboured broader opposition to continued Covid-19 mandates and restrictions – plus the support of hundreds of thousands more across the country, as well as millions of dollars in donations. During the episode’s peak, the Ottawa Police Service estimated the crowd at Parliament Hill ranged from 5,000 to 18,000 protesters.

There were also protests outside of Ottawa, including weekly rallies in most major cities across Canada and, most significantly, at the border crossings between Alberta and Montana at Coutts, between Ontario and Michigan at the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor, and at Emerson, Manitoba. The Coutts crossing was cleared by police after 17 days; the Ambassador Bridge was cleared after six days.

As days became weeks, the protests in Ottawa dwindled in size and were compressed into a small part of Ottawa’s downtown, mostly in the area of Wellington Street directly across from the Parliament Buildings. Although this was described in mainstream media, by Ottawa’s mayor, by the federal Liberals and NDP, and by other commentators as a “blockade” or “occupation,” on-the-scene eyewitnesses – including at least one Conservative MP – reported that pedestrians always had freedom of movement throughout the area.

Nonetheless, on February 14 Trudeau declared a public order emergency and invoked the federal Emergencies Act. He asserted that the continued protests in this small section of Ottawa now constituted a national emergency. While the protests were disruptive and violated a number of bylaws and traffic laws, there is no evidence, at least not public evidence, of serious criminality – much less that they represented a national emergency that could not be dealt through normal legal and law enforcement means.

As mentioned, the Emergencies Act has specific criteria that must be met for the law to be invoked. Every provision in it is designed to limit the federal Cabinet’s power to declare an emergency to only those situations where it is absolutely necessary, to grant to the Cabinet only the powers it needs to deal with that particular emergency, and for the powers to last only as long as the emergency in question.

The Act defines a national emergency as “an urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature that (a) seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians and is of such proportions or nature as to exceed the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it, or (b) seriously threatens the ability of the Government of Canada to preserve the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of Canada.” It also requires the federal government to demonstrate that the situation cannot be effectively dealt with under any other law of Canada.

Once a national emergency is declared, the Act gives the federal Cabinet the exceptional power to unilaterally proclaim a public order emergency. Doing so delegates vast legislative authority to the Cabinet – including the power to create new criminal offences and police powers, without recourse to Parliament, advance notice or public debate.

The Prime Minister’s invocation of this extraordinary legislation to address a discrete and shrinking protest in Ottawa was wholly improper and illegal. Protests aren’t emergencies, even if the protests are disruptive and even if the protests have illegal elements.

And that’s exactly what happened. The Trudeau Cabinet issued orders under the Emergencies Act creating a new crime of participating in a public assembly that may lead to a breach of the peace. There was no accompanying guidance on how to determine whether such a breach could be “reasonably expected.” The government – again, acting through the Cabinet, not Parliament – also issued orders requiring financial institutions to freeze bank accounts and report to law enforcement about people who were engaged in the Freedom Convoy protests. This warrantless search and freezing of accounts even applied to people who were indirectly assisting in the protests.

The Prime Minister’s invocation of this extraordinary legislation to address a discrete and shrinking protest in Ottawa was wholly improper and illegal. Protests aren’t emergencies, even if the protests are disruptive and even if the protests have illegal elements. The fact that the border blockades were being removed by law enforcement even as the Emergencies Act was invoked should have been evidence enough that the situation did not “exceed the capacity or authority” of the provinces to deal with it. Politicians and police must handle civil disobedience using the laws they have available to them rather than invoking emergency legislation whose criteria have not been met and which has a dark history of abuse.

Invoking the legislation when the criteria are not met normalizes governing by emergency order. It is an abuse of power. And, under the terms of the law itself, it is illegal. The freezing of bank accounts, even of of people only peripherally connected to the convoy protests, was a violation of their civil liberties. The measures also violated protected rights to freedom of assembly, association, expression and liberty under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

But the symmetry between the two Trudeau eras does not end with the abuse of civil liberties during a crisis, real (in Pierre’s case) or perceived (in Justin’s case). There is also a dark symmetry in the secrecy being deployed by the current government to stymie oversight of its illegal invocation of the Emergencies Act.

In the wake of the fiasco, a public inquiry was called into the use of the Emergencies Act, to be led by Ontario Superior Court Justice Paul Rouleau. This is not a noble act of transparency or introspection by the federal government, however. An inquiry is required under the Emergencies Act itself. As well, the Canadian Constitution Foundation and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association have each launched judicial challenges to its invocation.

Shown are the first pages of the War Measures Act (left) and of the McDonald Commission report (right). Struck to investigate RCMP wrongdoing in the wake of the October Crisis, the Commission called for change, which ultimately led to the Act’s repeal. (Sources of documents: (left) umanitoba.ca, (right) publicsafety.gc.ca)

Shown are the first pages of the War Measures Act (left) and of the McDonald Commission report (right). Struck to investigate RCMP wrongdoing in the wake of the October Crisis, the Commission called for change, which ultimately led to the Act’s repeal. (Sources of documents: (left) umanitoba.ca, (right) publicsafety.gc.ca)Because the deliberations of the Trudeau Cabinet were central throughout the events in question, a clear understanding of what went on within Cabinet is of obvious importance in evaluating what led up to the ultimate decision – its basis and rationale, whether it was justified, and why alternative courses of action were rejected. But access to Cabinet documents that could be used as evidence in these proceedings is being restricted by Trudeau Jr. Fittingly, or perhaps perversely, he is using a law enacted by his father in response to the McDonald Commission.

The history of this law is considered in detail in an excellent paper by Yan Campagnolo, a professor of law at the University of Ottawa and an expert on cabinet secrecy. During the McDonald Commission, Trudeau Senior gave in camera testimony wherein he was questioned about the substance of Cabinet discussions on the RCMP Security Service’s unlawful activities. The questions related to Cabinet minutes which had been in the RCMP’s possession and which the RCMP had neglected to return to the Privy Council Office (which is the secretariat to the federal Cabinet).

Trudeau Sr. was upset about the disclosure of Cabinet documents, especially in this context, stating, “I certainly wouldn’t want [these minutes] to be used as evidence against me.” He also later testified, “This just proves I was right in saying: don’t circulate these God-dammed minutes everywhere…these discussions between [ministers are privileged], and what the hell are they doing in these files of the RCMP.” (Emphasis in the Campagnolo paper).

Pierre Trudeau demanded amendments to Bill C-43 affording the highest level of protection to the whole sphere of Cabinet confidences. Further, to pre-empt judicial interpretation of that term, the legislation provided a non-exhaustive list of documents which were deemed to contain such confidences – that would be kept unavailable no matter what.

During the lead-up to his testimony, Parliament was in the process of amending legislation dealing with public-interest immunity of Cabinet confidences in the Access to Information Act and the Canada Evidence Act. Canada had extremely restrictive laws regarding access to Cabinet documents, which approached absolute immunity and were out of step with other Westminster-style systems.

Bill C-43 was meant to improve accountability and transparency. It proposed creating a right to access any government-held document. It would also add a provision to the Canada Evidence Act restoring the jurisdiction of the courts to assess all public-interest immunity claims, including Cabinet immunity claims at the federal level. The federal Minister of Communications, Francis Fox, stated that this would “create better conditions for the administration of justice by the courts.”

Bill C-43 received a second reading in the House of Commons in January 1981 and was referred to committee. Five days after its introduction, however, Trudeau was called to testify before the McDonald Commission. As a result of that testimony and the questioning of the Prime Minister about Cabinet minutes, he instructed Fox to hold up the bill.

These events coincided with two court decisions that permitted the disclosure of cabinet documents and the testimony of a minister on cabinet documents, Mannix v Alberta and Gloucester Properties v British Columbia (1982) 1 WWR 449 (CA). In those cases, the courts treated cabinet immunity in a non-deferential manner, and there was concern that while these were provincial decisions, the principles they articulated could creep into federal law.

Trudeau demanded – and got – amendments to Bill C-43 affording the highest level of protection to the whole sphere of Cabinet confidences. Further, to pre-empt judicial interpretation of that term, the legislation provided a non-exhaustive list of documents which were deemed to contain such confidences – in other words, that would be kept unavailable no matter what. And far from being discrete and limited, protecting only the most sensitive matters of direct Cabinet discussion, the list was incredibly broad. It included Cabinet memoranda, agenda minutes and decisions as well as ministerial communications and briefing notes on Cabinet business. It was also extended to discussion papers, draft legislation and any other document containing Cabinet confidences.

The result was nearly the opposite of what the McDonald Commission had demanded and what Minister Fox had promised. What passed was an amendment to what is now section 39 of the Canada Evidence Act (CEA) that preserves what some scholars describe as near-absolute immunity for Cabinet confidences, by giving them a greater level of protection than they would have under the Common Law. Under Common Law, Cabinet immunity is relative and not absolute; courts could order the disclosure of Cabinet secrets when it is in the interest of justice, and not all Cabinet secrets are of equal sensitivity.

Keeping secrets: Pierre Trudeau (shown in 1968 with a few Cabinet ministers) was enraged that the RCMP had possession of Cabinet documents. His laws to protect secrecy are giving Justin Trudeau’s Cabinet (bottom) the cover it needs to deny material to the judicial review of the Emergencies Act. (Source of photos: The Canadian Press)

But the Liberal government of Trudeau Sr. enacted legislation, including section 39 of the CEA, which has displaced this Common Law concept to give the government far more power to keep such records secret. It is this law, specifically section 39 of the CEA, that Trudeau Jr.’s government is relying on to prevent disclosure of documents related to the Emergencies Act.

These documents are the key to the court challenge brought by the Canadian Constitution Foundation. First, the government has withheld the minutes of the Incident Response Group and Cabinet from its response to the CCF judicial review. The Incident Response Group is a Cabinet committee specifically dedicated to advising the Prime Minister in the event of a national crisis. (Although the Prime Minister’s Office publicly announced the meetings of the group, and offered a long list of law enforcement agencies that briefed them, it did not reveal which ministers attended.)

The Trudeau government has presented an “official explanation” for the proclamation of an emergency, because this is required by section 58(1) of the Emergencies Act. But the explanation is thin. The document, tabled in Parliament, is unsigned and unsworn, and relies on the weakest of evidence, including things like CBC news reports and hacked data with no chain of custody. This can’t be sufficient to declare an emergency that is guaranteed to have a massive impact on our civil rights and to severely disrupt if not ruin the lives of individuals targeted. The sole meaningful item the official explanation mentions is “robust discussions at three meetings of the Incident Response Group on February 10, 12 and 13, 2022.” The relevant minutes should contain the details of that “robust discussion,” and the CCF is seeking to access them.

Second, the government is withholding the Minister of Public Safety’s submissions to Cabinet. These provided the factual and legal basis for the Emergencies Act’s use and the orders under it, like the order freezing bank accounts, or creating a new crime of participating in a public assembly that may lead to a breach of the peace.

As a result of the government withholding this material, the record that the court will see is nearly silent on the central legal question in the application for judicial review – whether the Cabinet had reasonable grounds to believe that the partial border blockades and the Ottawa protest could not be effectively dealt with under any other law of Canada, and whether those orders, like the freezing of accounts, were necessary. The record contains only a single conclusory sentence on this point: “The ongoing Freedom Convoy 2022 has created a critical, urgent, temporary situation that is national in scope and cannot effectively be dealt with under any other laws of Canada.”

This puts the court in an impossible position. To discharge its constitutional function, the court must have before it a full record. Without the materials the government is withholding, the court will be put in the position of acting as a fig leaf for the Trudeau government. The CCF has responded by bringing a motion asking the court to order the government to disclose this material. The organization is asking the court to order the government to deliver the minutes from Cabinet and the Incident Response Group, and any items listed in the Section 39 certificate, on a counsel-only basis under a confidentiality undertaking.

While CEA Section 39 would seem to present an insurmountable obstacle, the CCF is arguing that the Federal Court has plenary powers under Common Law to control the integrity of its own process, as part of its core function to preserve the rule of law. For judicial review to be effective, meaningful and fair, a court must have access to the materials before the decision-maker, which can be tested in an adversarial proceeding. Without this information, there may be gaps in the evidentiary record which may leave the government unable to demonstrate the reasonableness of its decision or undermine the requirement that there be a reasoned explanation for the decision to invoke the Emergencies Act.

The Justin Trudeau government invoked this extraordinary legislation, giving it powers that had a massive and potentially disastrous impact on Canadians’ civil rights, and it now claims that it does not need to explain why it did so – and that the documents that might shed light must remain secret and above scrutiny.

Counsel-only access has been used in the past, although in a slightly different context, for dealing with claims of national security rather than cabinet confidence. For example, in the prosecution over the 1985 bombing of Air India Flight 182, which killed all 329 people aboard, the prosecution permitted defence counsel access to withheld material on an undertaking not to disclose it to the accused.

We believe there is a compelling legal argument to do the same in this case. The Trudeau government invoked this extraordinary legislation, giving it powers that had a massive and potentially disastrous impact on Canadians’ civil rights, and it now claims that it does not need to explain why it did so – and that the documents that might shed light on its reasoning and rationale must remain secret and above scrutiny. In a very real sense, above the law itself. The court is being asked to accept the government’s say-so. To trust them. But as the CCF’s lawyer, Sujit Choudhry has said, that’s just not how we do law in this country.

In 2015 the Prime Minister spoke of doing things differently from his father. Of a more democratic and transparent government. Instead, the current Prime Minister has illegally invoked emergency legislation that was seriously reformed by his father to prevent abuse. He then relied on his father’s laws protecting cabinet confidences to maintain secrecy and avoid judicial scrutiny. A not-so sunny symmetry indeed.

Christine Van Geyn is litigation director at the Canadian Constitution Foundation.

Source of right part of main image: The Canadian Press/ Adrian Wyld.