From a very young age, I have performed academically at a high level. When I started elementary school, my reading and math abilities were already significantly above those of my classmates. At age 6, my parents took me to see a psychologist who gave me an IQ test. I was assessed as being “intellectually gifted”, with a score in the top 2 percent of the population. You might think that has made my life easy. It hasn’t.

Following that assessment, my parents tried very hard to find a way for me to succeed in Alberta’s public education system. They discussed with administrators and teachers at my elementary school the possibility of creating a specialized curriculum for me, or accelerating my progress by a grade or two. Unfortunately, the school was unwilling to provide any meaningful enrichment and I was not permitted to skip any grades, due to concerns about my future socialization.

As a result, I remained thoroughly unchallenged in all my classes. Whenever math worksheets were handed out, I would rush through them as fast as I could in order to have some free time to read a book. This boredom led to behavioural issues. I frequently played the class clown by interrupting regular classroom activities to get a laugh out of the other students. When teachers were giving instructions, I would talk to my friends and ignore what the teacher was saying. Because of this, I was routinely sent to the hallway, or sometimes to the principal’s office.

My parents transferred me to two other schools in search of a solution. Neither was a good fit. When I turned 8, they enrolled me in an after-school mathematics enrichment program in hopes that it would challenge me outside the classroom. This allowed me to grapple with material substantially ahead of the public-school curriculum, such as fractions. But while it was an improvement, it wasn’t as advanced as I wanted, and I’d already learned much of the content on my own.

In Grade 5, I finally found a school that offered me an appropriate academic challenge – Westmount Charter School. Westmount operates as the only congregated kindergarten to Grade 12 program for gifted students in Alberta. This was an academic environment that finally presented me with a meaningful challenge in all subjects. Students were allowed to dig deep into the material in ways that would not be possible at other schools. Older students were encouraged to explore their personal interests through a “passion project”.

Several times a year, students at Westmount construct and review their own Individualized Program Planning (IPP) document. This encourages students to set goals for their academic or personal development, and allows teachers and staff to modify their practices to better fit the students’ needs. My IPP allowed me to move ahead in mathematics; while still in Grade 5, I was placed in Grade 7 math. This was not an uncommon practice; of the 100 students in my grade, about a dozen were a year ahead in math and ten were two years ahead. A few were even more advanced.

With these new academic opportunities came new personal hurdles, however. At other schools, I had succeeded without studying or doing any homework. Now, I had to do real work. But because of the time I’d spent stagnating in those earlier schools, I’d never learned good study habits. I began to struggle in some subjects and was eventually assigned a learning assistant. I had to repeat Math 8 twice due to a poor study routine. Only when I hit my teenage years did I fully adjust to the tougher curriculum. At this point I was ahead by one year in math.

The situation at Westmount was good, but not ideal, as the school does not treat all subjects equally. For example, another student tried to accelerate in humanities, which at Westmount combines English and social studies. But to do so, this student had to demonstrate a level of understanding significantly higher than other students in the grade he was trying to move into. This is a very high bar.

In an environment composed exclusively of highly-intelligent individuals, it seems reasonable that all or almost all students would be performing at least a year or two ahead of their public school peers in all subjects – especially given the high correspondence between cognitive abilities across domains. Yet the full-grade skipping rate at Westmount was comparable to that of non-gifted students in public schools, with only 1 or 2 percent of students skipping at least one grade in all subjects. Even at Westmount, structural barriers were preventing students from reaching the level best aligned with their abilities.

A study by researchers from Vanderbilt University that looked exclusively at mathematically precocious students found that those who skipped grades were more likely to pursue advanced degrees in STEM fields and to produce publications in peer-reviewed academic journals.

Despite these and other limitations, my time at Westmount was a positive experience, and significantly better than any other school I could have attended. In fact, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity; Westmount has a very long waiting list and some families have to wait years before their children are accepted, if they are at all.

I also appreciated the opportunity to meet a number of exceptional people I wouldn’t have met otherwise. Being surrounded by peers who are extremely knowledgeable about politics and philosophy for their age honed my reasoning abilities and knowledge in special ways. Even at university today, I struggle to meet students with whom I can engage to the same degree. From this perspective, Westmount represents a concrete example of the benefits associated with segregating and accelerating gifted students.

Age Trumps Ability

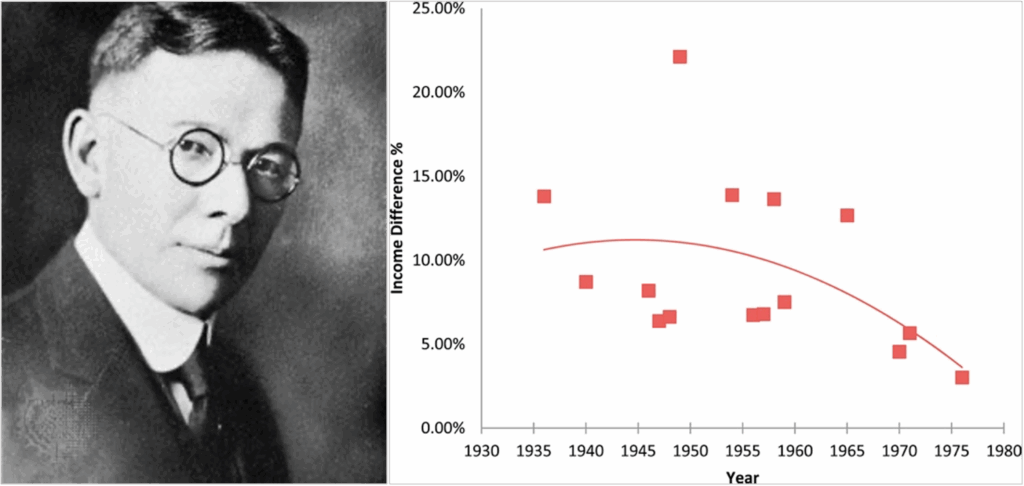

Research shows that special treatment for gifted students leads to clear benefits over the long run. Data from what is called the Terman Sample, a cohort of gifted students (all with IQs above 135) in the U.S. who were followed by Stanford University researcher Lewis Terman from 1936 to 1976, found that male students who skipped a grade went on to earn up to 10 percent more annually that those who did not skip. The result for females was somewhat lower, but still significant.

A similar investigation published in the Journal of School Psychology using different data confirms the earning advantage for gifted grade-skippers – although in this case, women outperformed men. And a study by researchers from Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee that looked exclusively at mathematically precocious students (within the top 1 percent of their cohort) found that those who skipped grades were more likely to pursue advanced degrees in STEM fields and to produce publications in peer-reviewed academic journals – and both at an earlier age than is average. (The women in this group were more likely to pursue medicine and law.)

Despite what the evidence shows, however, the education systems in the U.S. and Canada have generally followed a policy that favours age over ability. The preference is always to group students by their birth year rather than by what they can actually accomplish in the classroom. As a result, acceleration is significantly more difficult than it should be, which hinders the development of students who have stronger talents. This is substantially different from standard policy across Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, when acceleration was actively encouraged.

As I found out through personal experience, gifted children can get by in a typical class without studying or working hard. This means they miss out on mastering learning habits that will be necessary later in life. Without the need to work hard early on, gifted children have a tendency to struggle later on when faced with real adversity. By denying them these crucial experiences at an early age, the school system is not just ignoring gifted children; it is actually harming them. As pop psychiatrist Alok Kanojia explained on his podcast The Healthy Gamer, “Society sets the gifted child up to fail.” Kanojia added that, “When we think of the gifted child, we perceive that being gifted is an advantage. But in my experience, working with a lot of gifted children…quite often it can be a burden.”

This is a much bigger problem than might be assumed. While Canadian data are scarce, a 2016 report from the Johns Hopkins School of Education found that between 15 percent and 45 percent of U.S. students enter late-elementary classes each fall already performing at least one year ahead of standard academic expectations. Such a statistic may seem at odds with frequent reports that millions of U.S. children are underperforming in school by multiple grades and that some even graduate high school unable to read or write. But both trends can be true at the same time. “The current K-12 education system essentially ignores the learning needs of a huge percentage of its students,” the Johns Hopkins report states, adding that this reveals a “need to re-think the merits of an age-based, grade-level focus” in the national school system. There is no reason to assume the results are any different for Canada.

How is giftedness related to achievement later in life?

Research shows a clear connection between early giftedness and later academic and professional achievement. Gifted students who are allowed to skip school grades are more likely to pursue advanced degrees in STEM fields and publish in peer-reviewed journals. They also tend to earn more – up to 10 percent more annually.

No Place Like Homeschool

In some cases, parents who have sufficient financial means will take their exceptional children out of the public education system altogether. Peter Osiowy had a similar experience to my own as a gifted student in Calgary’s elementary school system. After moving from school to school for many years, his parents finally decided he needed to be homeschooled. “I was being handicapped because I was ready to go much further than the rest of the class,” Osiowy says in an interview, recalling that in Grade 1 he was ready to learn algebra; his teachers gave him colouring projects instead. From Grades 6 to 9 he was exclusively homeschooled by his mother, who was a teacher and had the relevant background and skills to assist him. She offered her son significant autonomy over what he studied, allowing him to seek challenges markedly beyond those given to similar-aged public school kids. “Whenever we looked at the learning outcomes, I was four or five years ahead of what other students were doing,” he notes.

For Grades 10 to 12, Osiowy attended classes at Bishop Carroll High School in Calgary, which allowed him to pursue coursework at a self-directed pace. He is now a psychology student at the University of Calgary. Overall, Osiowy says his schooling experiences have been beneficial; yet that success depended on his parents having the resources and skills to meet his needs at home. These are advantages not every gifted student enjoys. “There are a lot of families that just aren’t set up to homeschool,” he acknowledges. Given the scale and scope of provincial taxes that go to the education system, it shouldn’t be the responsibility of parents to shoulder the burden of educating their own exceptional children.

The Enemies of Scholastic Elitism

There are plenty of critics opposed to accelerating, streaming or grouping gifted or advanced students. Unfortunately, most of them seem to work in Canada’s public school systems.

One common criticism is that such policies risk harming the education of the other, average and/or weaker students. Since a lot of classroom learning involves students communicating and collaborating with one another, the argument goes, removing the smartest students will inhibit the others’ progress. While such an effect might seem plausible in isolation, the available academic evidence shows classroom groupings based on scholastic performance have no impact on students of average or below-average ability.

A study in the journal Gifted Child Quarterly states that, “Results do not support recent claims that no one benefits from grouping or that students in the lower groups are harmed academically and emotionally by grouping.” In fact, removing disruptive gifted students from the average classroom may actually benefit the classmates left behind, as my own experience demonstrates. There are real downsides to deliberately fostering classroom boredom.

A second concern is that children who accelerate grades risk under-developing their social skills because they are put in environments with older peers. The 2015 book A Nation Empowered: Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students tackles what the authors call “the ‘myths’ of social maladjustment and psychological problems” arising from grade skipping. Such a belief, they write, “may have deterred educational leaders from considering more of their brightest students for some form of acceleration, whether grade-based or subject-based.” Other research finds that “academic acceleration produces small-to-moderate social-emotional gains for these students.” It seems that when students are surrounded by others of a similar ability, they form more meaningful connections and are less likely to socially isolate themselves.

Osiowy says this issue was also often raised with regards to his own homeschooling. But, he rebuts, “I never had any concerns about my social life,” explaining that he had plenty of friends since homeschooling provided more flexibility in socializing with others. “My junior high years were by far the happiest period of my life,” Osiowy recalls. Academic evidence shows homeschooled children score significantly above average in achievement tests as well as being above the bar on measures of social, emotional and psychological development.

What are the characteristics of gifted children in the classroom?

Gifted children often complete assignments much faster than their peers. If they are not sufficiently challenged by their school work, however, they may become bored and act out. They may also develop poor study habits, which can impede their progress later in life.

Nature Versus Nurture

There is a reason that people who do well on intelligence tests are called “gifted” as opposed to “accomplished”. In the same way that some individuals are born taller than average, more athletic or more sociable, some individuals are simply born with a higher IQ than others. It is a “gift” that is received rather than something earned or achieved.

The issue of how to treat gifted students in the public school system comes down to the eternal debate between nature and nurture. Nurture refers to the environment in which a child grows up and experiences life, and which may be malleable through public policy. Nature refers to the innate talents and abilities that vary from person to person and are beyond the power of any government to alter. Both factors are obviously important. But many who advocate for a one-size-fits-all education system seem to think schooling (i.e., nurturing) can eradicate any innate differences in ability and thus overcome the effects nature has created.

Education has its limits, however. Research shows the significance of a person’s environment or upbringing actually decreases over time. While primary and secondary schooling are essential for teaching students basic skills like reading and writing that are necessary for life in the real world, schooling has little influence on the underlying cognitive faculties of students. Interventions that attempt to raise the intelligence of targeted students have been proven to have no permanent impact. As a 2015 meta-analysis covering 39 randomized controlled experiments reveals, “After an intervention that raises intelligence ends, the effects fade away.”

Busting the “myth” of social maladjustment: According to the 2015 book A Nation Empowered: Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students, grade skippers do not suffer a social penalty from studying with older students. Other similar research finds “academic acceleration produces small-to-moderate social-emotional gains for these students.”

Busting the “myth” of social maladjustment: According to the 2015 book A Nation Empowered: Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students, grade skippers do not suffer a social penalty from studying with older students. Other similar research finds “academic acceleration produces small-to-moderate social-emotional gains for these students.”On the other hand, the heritability of cognitive ability appears to increase with age. In childhood, the share of an offspring’s IQ explained by that of their parents’ stands at about 40 percent; in adulthood, it’s well over 60 percent. That genetics appears to have an expanding impact on intelligence and performance as time goes on has been dubbed the Wilson Effect. This surprisingly robust result is named for University of Louisville behavioural geneticist Ronald Wilson, whose famous 1983 study of 500 pairs of monozygotic (or identical) twins first revealed the phenomenon. Acknowledging the Wilson Effect may sit awkwardly or uncomfortably with today’s equity-obsessed world. But that doesn’t change the facts on the ground.

The practical implications of efforts to socially engineer student outcomes – something that was gathering steam for the past 50 years but went into overdrive with the ascendance of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and critical race theory (CRT) – are all around us. Policy makers today appear determined to achieve equality in outcomes regardless of the consequences. As has been well-documented elsewhere, this trend took off in the wake of the George Floyd murder in Minneapolis in 2020. In response, numerous school boards across North America embraced the politics of enforced equity and inclusion. In 2021, for example, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio announced he would eliminate the selective gifted student program for all city public schools, along with the qualifying exams meant to identify such students. He portrayed his move as a blow against segregation, and therefore inequality, in the school system.

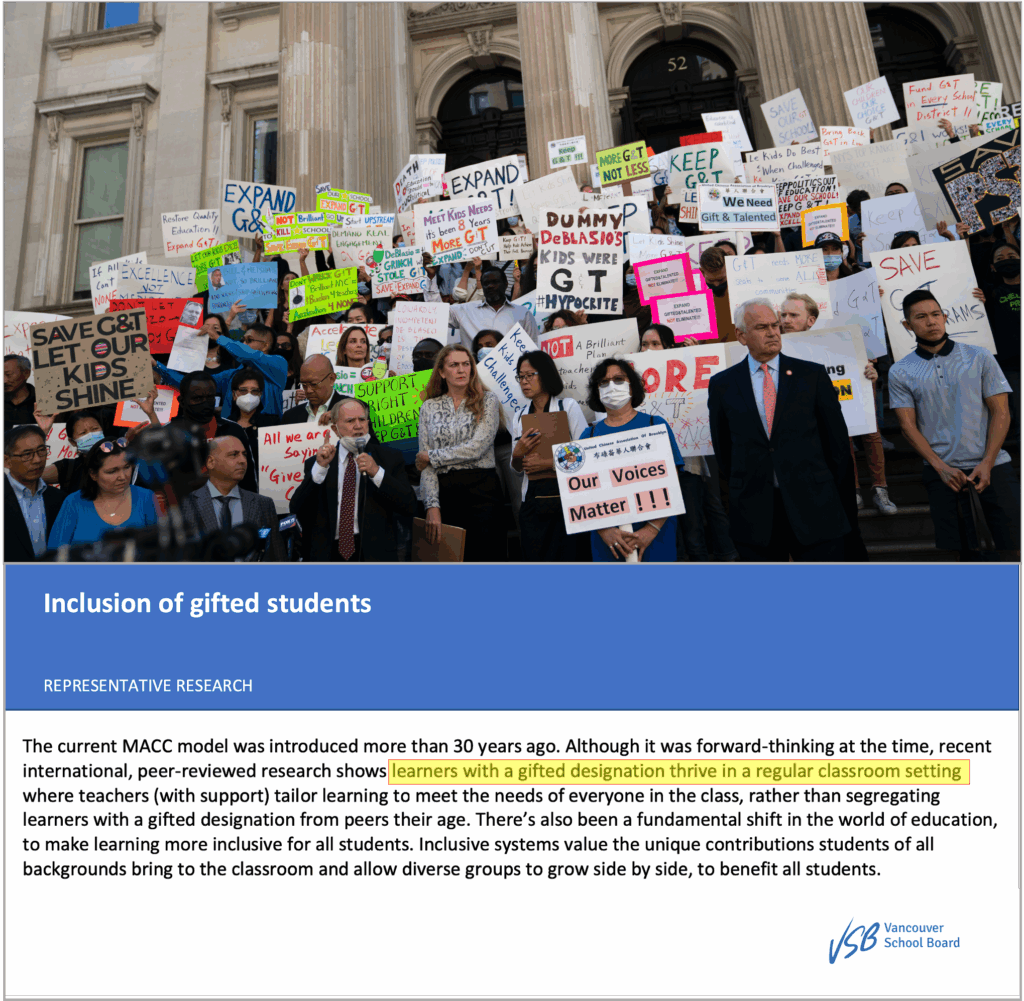

The Vancouver School Board (VSB) made a similar announcement the same year, pausing an accelerated learning program that prepared high school students for university study. It also significantly downsized a multi-age cluster class (MACC) program for high-IQ children in Grades 5 to 7, again citing concerns about inclusion. As a VSB report on the MACC changes explained (entirely incorrectly in my opinion and experience), “Research shows students with a gifted designation thrive in a regular classroom setting where teachers (with support) tailor learning to meet the needs of everyone in the class, rather than segregating learners with a gifted designation from peers their age.”

DEI ideology plays the central role in the VSB’s statement. “There’s…been a fundamental shift in the world of education, to make learning more inclusive for all students,” it reads. “Inclusive systems value the unique contributions students of all backgrounds bring to the classroom and allow diverse groups to grow side by side, to benefit all students.” Based on the supporting evidence its supplies, the underlying goal of this document appears to be the inclusion of students with disabilities in regular classrooms. And to do this, it is necessary to discourage segregation in all forms, including that of gifted students based on ability. But regardless of how such a policy may affect disabled students, it will not make life easier for above-average students.

Special programs, including academic segregation, are essential to the well-being of gifted students and the fulfillment of their personal destinies. Ignoring the needs of these students is not just bad policy. It is fundamentally unfair.

Given the entrenchment of DEI and CRT in North America’s schools, opinions about gifted programs will be difficult to reverse. While de Blasio’s successor Eric Adams has undone some of the cuts to New York City’s program, elsewhere the trend continues; last year Seattle, for example, closed its own gifted programs in the name of diversity and equity.

Why are gifted schools and programs being shut down in Canada?

Some schools boards in Canada and the U.S. have closed or reduced programs for gifted students in the name of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). The Vancouver School Board, for example, paused an accelerated learning program and downsized a cluster class for high-IQ children, erroneously claiming students with gifted designations “thrive” in regular classrooms.

Small Poppies Need to Grow Tall

The popular characterization of segregation policies for gifted students – including streaming and acceleration – as a form of discrimination against other students is utterly wrong and based on the fallacious assumption that any disparity in outcome must be due to societal unfairness of some sort. But segregating by ability is fundamentally different from racial segregation or any other form of prejudice. As we have seen, intelligence is not distributed evenly across a population, and for reasons that are difficult or impossible to change. Further, special programs, including academic segregation, are essential to the well-being of gifted students and the fulfillment of their personal destinies. Ignoring the needs of these students is not just bad policy. It is fundamentally unfair.

This point was made most eloquently by Miraca Gross, an expert on gifted education at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Her 1999 article Small Poppies: Highly Gifted Children in the Early Years is now considered a classic text in recognizing the needs of exceptionally intelligent students. The term “small poppies” refers to the Aussie habit of disparaging or attacking boastful high-achievers, better known as the “tall poppy syndrome”. As Gross wrote:

“We recognize that for a child with unusual sporting or athletic ability who longs to fulfill her potential, ‘the pursuit of happiness’ implicitly involves her right to strive to develop her talent to the fullest possible extent. Our bias becomes apparent, however, when the child’s precocity is sited in the cognitive domain. Intellectually gifted young children are much less acceptable to the general and educational community than are their physically gifted age-peers, and their efforts to develop their talents are too often greeted with apathy, lack of understanding, or open hostility. It is time that we acknowledged and addressed this bias so that all our small poppies may lift their heads to the sky.”

Canadians are rightly outraged by discrimination of all kinds. The discrimination occurring today in Canada’s schools is one based on age-based prejudice and policy rigidity. And it is harming gifted children. Students who can perform a year or two ahead of their grade level are being held back while students who can’t perform at their grade level are allowed to progress through the system – all in the name of equity. But trying to equalize age-based outcomes in this way won’t make mediocre students exceptional. It only makes exceptional students miserable…and given time, mediocre as well.

The current treatment of gifted students in public school systems across Canada amounts to a waste of human talent. As we have seen, students who are allowed to accelerate are more likely to pursue advanced degrees in key subject areas and to produce peer-reviewed publications sooner. Imagine how many innovations might be delayed or lost altogether because of Canada’s one-size-fits-all approach. It is time to get rid of the arbitrary and outdated age-based barriers for grade advancement and once again consider students on the basis of merit – as Canadian schools once did.

Jonathan Barazzutti is an economics student at the University of Calgary. He was the winner of the 2nd Annual Patricia Trottier and Gwyn Morgan Student Essay Contest co-sponsored by C2C Journal.

Source of main image: Screenshot from For The Birds by Pixar.