All politics is local, the saying goes. The same applies to washrooms. When you need to go, all that really matters is the state of the nearest washroom. And in southwestern Ontario’s Waterloo Region, where I live, something very peculiar is happening to the local washrooms. Case in point is Kitchener’s Centre in the Square, the area’s premier soft-seat performance venue that hosts a wide range of popular musicians and other acts.

Prior to renovations in 2023, the 2,000-seat facility had eight washrooms serving patrons on the auditorium’s main and balcony levels – four men’s and four women’s. Following a $2.4 million project primarily funded by federal and provincial grants, however, Centre in the Square took on an entirely different look. Now there are five unisex washrooms, two men’s rooms and a single women’s room spread across the two floors.

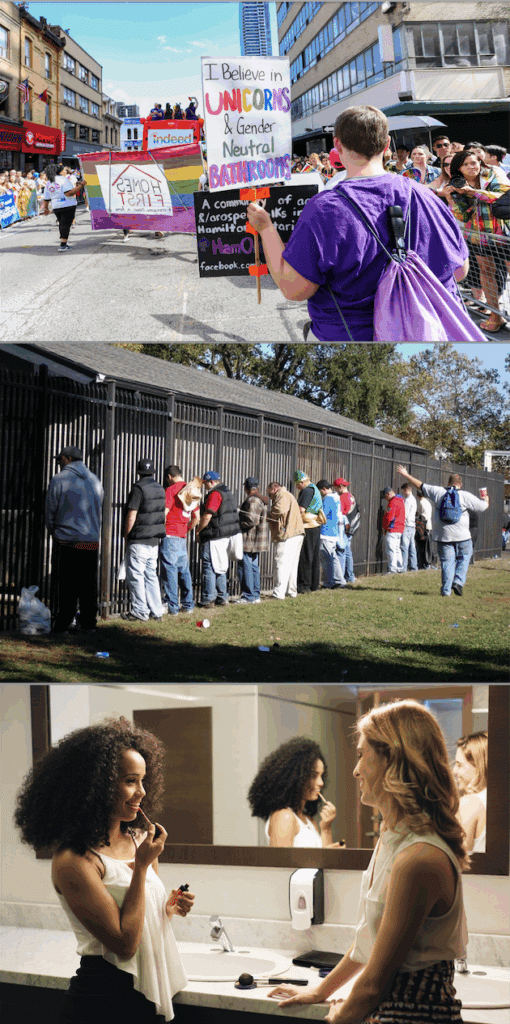

On the main floor where the bulk of the audience sits, the entire right side of the house is served by two large unisex washrooms. Here men and women must line up together to access a series of individual stalls that each contain a toilet, paper dispenser and garbage can. Everyone then shares a common bank of sinks and mirrors. This new arrangement, which upends centuries of sex-separated bathrooms, brings with it plenty of double-takes, puzzled looks and awkward moments. (Including when I took my 89-year-old mother to the Nutcracker.) But it is by no means unique.

Elsewhere in Waterloo Region, plenty of other public and private facilities now expect people of both sexes to use the same washroom. The University of Waterloo, for example, has numerous “universal” washrooms scattered across its campus, many of which consist exclusively of multiple toilet stalls. Restaurants have also embraced the move, including Four Fathers Brewing Co. in Cambridge, which offers guests six individuals washrooms open to both sexes, each with a toilet, sink and other necessities.

Whatever these gender-neutral washrooms are meant to provide, there’s one thing they lack: urinals. Amid current efforts to make restrooms more “inclusive”, the urinal – a uniquely male waste management device – is at risk of being cast aside forever. Perhaps it’s time someone stood up for this unloved, overlooked and sometimes malodorous necessity.

Potty Parity

Across North America, the gender-neutral washroom is a trend on the march. “Adding universal washrooms provides more options, helps ease lineups and congestion in high-traffic areas, and allows guests to choose the space that best suits their needs,” replies Jonathan Randall, Director of Marketing & Development at Centre in the Square, when asked about the changes to his facility. “These washrooms are especially helpful for families, caregivers, and those who may require more privacy or flexibility.”

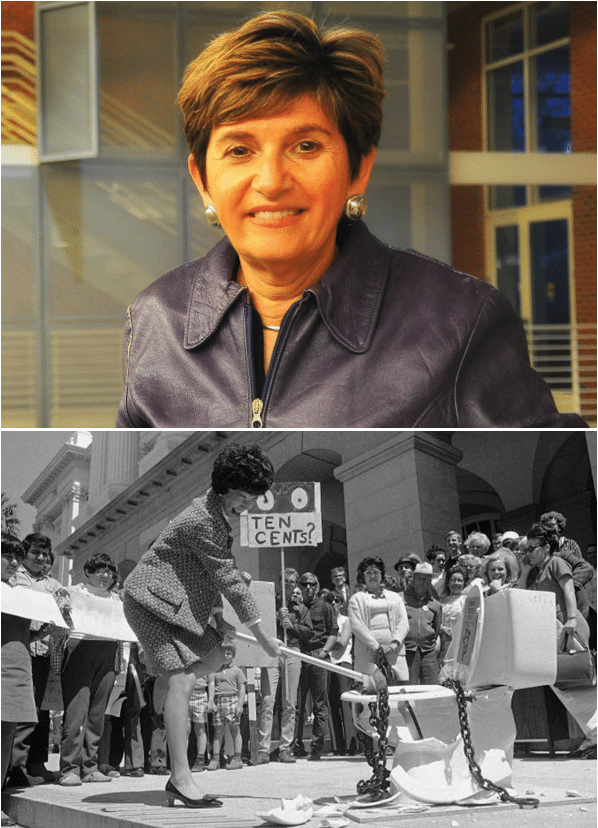

The ongoing disappearance of separate men’s and women’s rooms is part of a movement towards greater washroom equality, explains Kathryn Anthony. Anthony is a professor of architecture at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, former vice-president of the American Restroom Association and a widely-quoted expert on bathroom politics.

“Public restrooms have historically been places that privilege one group over another,” Anthony states in an interview, citing as examples of such discrimination “Whites Only” washrooms in the American South during the Jim Crow-era plus a dearth of wheelchair-accessible toilets that has only recently been rectified. But it is for her fight for equality between the sexes – what she calls “potty parity” – that Anthony is best known.

“Potty parity means equal speed of access to public toilets for men and women,” she says. “Women simply take longer to go due to our anatomy and the need to disrobe. So, we’re disadvantaged.” According to a variety of peer-reviewed data, women spend about twice as long in public restrooms as men when urinating. One recent academic study puts the gap at 50 seconds for men and 100 seconds for women. (Time spent on “#2” is the same for both sexes, at 420 seconds.) Another observational survey from 1988 set the washroom gender divide at 84 seconds versus 153 seconds.

Because of these innate differences, Anthony argues that simply providing an equal number of toilets for women and men won’t do. Rather, she argues, fairness dictates that women must be provided with substantially more toilets to equalize their time lining up and using the facilities. Citing as inspiration former California Secretary of State March Fong Eu, who smashed a toilet on the steps of Capitol Hill in 1974 in a protest against washroom inequities, Anthony has spent decades lobbying for rules requiring a greater share of toilets for women, including before U.S. Congress in 2010. Her efforts received wide acclaim in 2009 when the new Yankee Stadium opened in New York and reflected a civic ordinance requiring at least 358 toilets for women and 176 for men. Across the U.S., many cities and states now mandate twice as many toilets for women as for men.

In Canada, the concept of potty parity is already well-established. Since 1953 the country’s national building code has required a larger number of facilities for women than men in all public buildings. The current version, overseen by the Canadian Board of Harmonized Construction Codes, mandates twice as many “water closets” for women. In a building with a capacity of 251 to 300 people, for example, the code calls for a minimum of five water closets for men (either toilets or urinals) and ten for women.

Rise of the Genderless Washrooms

Despite many significant changes, Anthony insists there’s still much to do. “I still see lots of lineups at [women’s] restrooms,” she observes. “While things have improved, it’s not what it should be.” To rectify the lingering line-ups even when women’s bathrooms contain twice as many toilets as men’s rooms, Anthony now argues for erasing the separation altogether – making common cause with other activists seeking to break down binary gender definitions. “We are seeing more and more genderless, multi-stall restrooms,” she states. “It’s definitely the wave of the future and I think that it’s really good.”

‘When you convert to a genderless restroom,’ Anthony admits, ‘the urinals are removed. And as we see more and more unisex restrooms, we will see fewer and fewer urinals.’

Anthony stresses that the single-stall wheelchair-accessible washrooms now required in all buildings are no substitute for large-capacity multi-stall fixtures because they don’t target the entire population. As an example of a proper, fully-inclusive universal washroom, she highlights unisex facilities at the popular La Jolla Shores beach in San Diego, California, where she currently lives. “It used to be that men and boys would be in and out in a flash, while women and girls got stuck with long lines. Now this is a huge improvement,” she says, pointing to one long line in which everyone must wait. On hearing of the recent washroom renovation at Kitchener’s Centre in the Square, Anthony crows, “That’s excellent!” Both examples, she says, are signs of true equality since the male and female experience is now identical. Yet every blow struck for equality of washroom waiting times entails a loss somewhere else. And for men, it means the end of the urinal.

“When you convert to a genderless restroom,” Anthony admits, “the urinals are removed. And as we see more and more unisex restrooms, we will see fewer and fewer urinals.” Noting that most people do not have urinals in their homes, Anthony suspects few will miss them in public spaces either. She also claims that many men do not like to use urinals because of paruresis, or shy bladder syndrome, which makes it difficult for sufferers to urinate when someone is standing beside them. “I think their days are numbered,” she says, writing the urinal’s early epitaph. “And not too many people are going to be sorry about that.”

What is a multi-stall gender-neutral bathroom?

Sunset on the Urinal?

Evidence from a wide variety of sources seems to bolster Anthony’s claim. In 2017, for example, the U.S. Navy made waves when it announced that its newest aircraft carrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, would sail sans urinals. All “heads”, as washrooms are known in maritime parlance, are gender-neutral and comprised exclusively of toilets to accommodate the 18 percent of sailors who are female. “This is designed to give the ship flexibility because there aren’t any berthing areas that are dedicated to one sex or the other,” Operations Specialist 1st class Kaylea Motsenbocker told the newspaper Navy Times when the ship launched.

Other signs and portents further suggest the urinal’s end may be nigh. Universities seem particularly eager to do away with them as they seek to appease noisy activists who claim separate male and female washrooms discriminate against trans-gender people. At Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, a 2021 report from the Provost’s Action Group on Gender and Sexual Diversity declared designated male and female washrooms to be “exclusionary as they literally are designed to exclude users outside a specific gender.”

To rectify this situation, the report calls for replacing up to half of all existing sex-differentiated washrooms with gender-neutral versions; regarding urinals, it says it may be necessary to “remove such amenities entirely” from campus to achieve true fairness. (It also argues that all changerooms at the school’s athletic facilities should be made genderless. And it notes darkly that “male-designated facilities frequently fail to address the needs of people who are pregnant.”)

Many universities are already implementing a comprehensive gender-neutral vision for their restrooms. Last year, for example, the Université de Montréal unveiled a striking new lounge-cum-unisex bathroom in Pavillon J.-A.-DeSève, its student services building, that features a unique circular design with couches and study rooms meant to encourage students to linger all day long. With respect to more practical considerations, each stall has a floor-to-ceiling door for privacy and is separately ventilated. And there are no urinals.

Maud Jobert is an associate with Figurr Architects Collective, the Montreal-based firm that designed the bathrooms to the school’s specifications – a concept Figurr now promotes as Washrooms for All. As Joubert explains, “Inclusiveness was the university’s number one priority. There was to be no separation of gender. You just walk in and find a place to go.” As for the fate of the urinal in such a hyper-inclusive world, she admits that “urinals are not there…because women can’t use them.”

The same thinking has apparently taken hold in government circles, largely due to 2017 federal legislation that added “gender identity and gender expression” to the list of prohibited grounds for discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act. Advocates now claim this change enshrines a universal right to unisex washrooms everywhere. In 2021 Parks Canada issued a “Directive on Inclusive Sanitary Facility Design” that requires all new and newly-renovated park buildings to have gender-inclusive washrooms. The 2019 report that led to this directive cites the human rights law amendment directly and offers numerous washroom design options to meet this alleged obligation; none involve urinals.

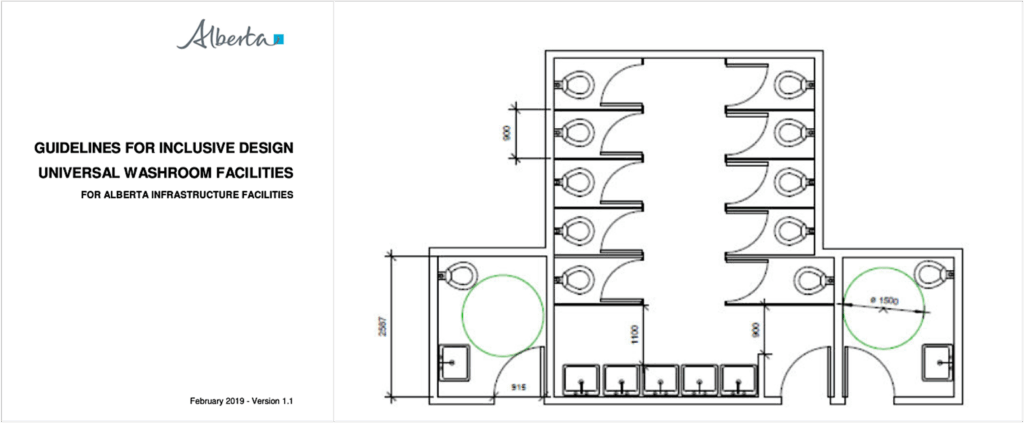

Similarly in Alberta, a 2019 document Guidelines for Inclusive Design Universal Washroom Facilities released by the former NDP government again references the 2017 federal legislation and sets out design parameters for public buildings specifying that “urinals will not be provided in new builds” because they are not inclusive. Canada’s National Model Building Code is also being updated to incorporate gender-neutral washroom standards that need not include urinals.

Things seem to be looking grim for the wall-mounted chamber pot.

Pee Here, and Quickly

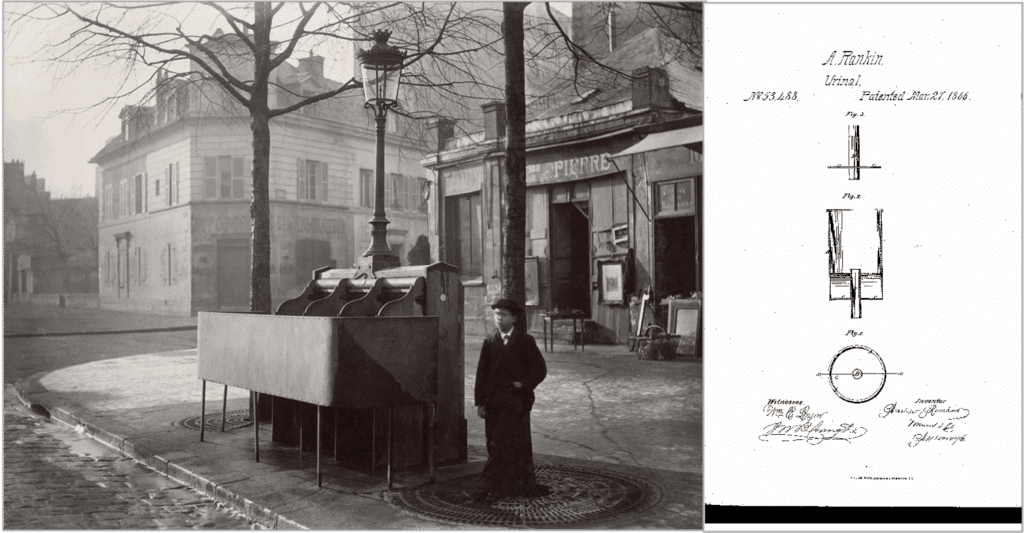

While trees and fenceposts have served the purpose from time immemorial, the modern urinal owes its origins to the rise of factories during the Industrial Revolution, which necessitated a way for male workers to relieve themselves quickly on the job. Beginning in the 1830s, city officials in Paris began installing rudimentary public urinals on street corners – later known as pissoirs – to meet the needs of male passersby caught short, and to improve overall public health. The first urinal patent was granted to inventor Andrew Rankin of New York City in 1865 for a disinfectant system to eliminate odours emanating from the by-then-ubiquitous devices; as Rankin’s patent explains, urinals were “frequently employed in railroad depots, ferry-houses and other places of public resort.”

All urinals save water – their second major benefit. Canada’s National Plumbing Code requires that a standard urinal consume no more than 1.9 litres per flush. That compares with 6 litres for toilets.

The ceramic urinal and its variants – including trough-like contraptions often found behind European pubs which enable men to jam together for maximum throughput – can be found across the world. And while the urinal today may be suffering from a noticeable lack of public support, it remains a marvel of utility and efficiency. Some of these benefits may only be enjoyed by half the population, but it outperforms its toilet competition across numerous and important measures, and in ways that should interest everyone.

First, the urinal is the fastest option for men. “Urinals have always served an important purpose in allowing men to pee standing up,” says Klaus Reichardt. “And that means we can get in and out of the restroom quicker.” Reichardt is founder and president of Waterless Co. Inc., a California-based company that makes waterless urinals. In 1991 he invented a system similar in intent to Rankin’s 1865 innovation that uses an oil-filled cartridge in the drain to cut the smell from urinals and which eliminates the need to flush away the waste with water. “You don’t need liquid to flush a liquid,” Reichardt points out in an interview.

While Reichardt’s system uses no water at all, all urinals save a lot water – their second major benefit. Canada’s National Plumbing Code requires that a standard urinal consume no more than 1.9 litres per flush. That compares with 6 litres for toilets designated for industrial, commercial or institutional use. In other words, a standard urinal uses one-third the water to perform the same task as a toilet when used by a male in any public building. A man forced into a unisex toilet is thus wasting up to 4.1 litres of potable water with every flush. Scaled up over hundreds of millions of flushes across the country for half the population, it is an enormous amount of lost water.

“Water conservation has become a huge issue,” says Reichardt, whose home state is frequently stricken by droughts. In fact, he cites the skyrocketing cost of municipal water in California as a major factor in his company’s success. “If we only offer toilets for men, we are going to increase water usage tremendously,” he warns. While advocates of gender-neutral washrooms typically see themselves as crusaders for gender equity, they are also inadvertent proponents of a vast amount of environmental waste.

Urinals are also excellent space-savers, both directly and indirectly. Regarding the urinal-less USS Gerald R. Ford, Chad Kaufman, president of the Public Restroom Company – a Nevada-based firm that installs washrooms in parks and other public spaces – told Navy Times that a standard urinal takes up less than half the floor space of a toilet stall. “Why would you want your ship to be bigger just for fixtures?” he asked. “You can get twice as many urinals as water closets.” In any large public facility, including sports stadiums and concert halls, the urinal’s quicker service time and smaller footprint for men means more room for larger washrooms for women.

Curiously enough, urinals also offer the opportunity to harvest a product very high in nitrogen and phosphorus as a potential source of fertilizer. Reinhardt eagerly supplies several studies revealing the efficacy of using his waterless urinals to collect undiluted urine for such efforts. One example is a January 2025 study by Spanish researchers in the academic journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling (impishly titled “Urine Luck”) reporting that 1 cubic metre of “yellow water” can help produce 2.4 tons of hydroponic tomatoes. In another, a team from Norway used urine to grow microalgae outdoors in the forbidding Nordic climate.

Is Your Aim True?

Urinals outperform toilets by every standard measure of efficiency: time, space, cost, environmental impact and resource collection – and are for men far more convenient to boot. But there is one category in which the disappearance of urinals will leave women noticeably worse off. Not efficiency, but accuracy. When urinals are replaced with unisex toilet stalls, men will inevitably use them to pee standing up. And because their aim is not always very good, women who enter immediately after a man has just left can face an annoyingly messy situation.

Every woman I have discussed this with expressed immediate revulsion at sharing toilets with men in busy public bathrooms. Such anecdotal evidence is backed by polling data. A 2015 survey of women conducted by U.S. modular bathroom manufacturer Green Flush Restrooms revealed that “two-thirds of respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘definitely agreed’ that they prefer to use restrooms that are only used by women.” Why? According to the survey, many women expressed “the frustration of sitting down on a toilet seat that men have urinated on.” A similar survey by British bathroom fixture supplier Formica yielded an identical two-thirds preference plus, worrisomely, found that 18 percent of women would “actually try to use the toilet less” if there were only unisex washrooms at their place of work.

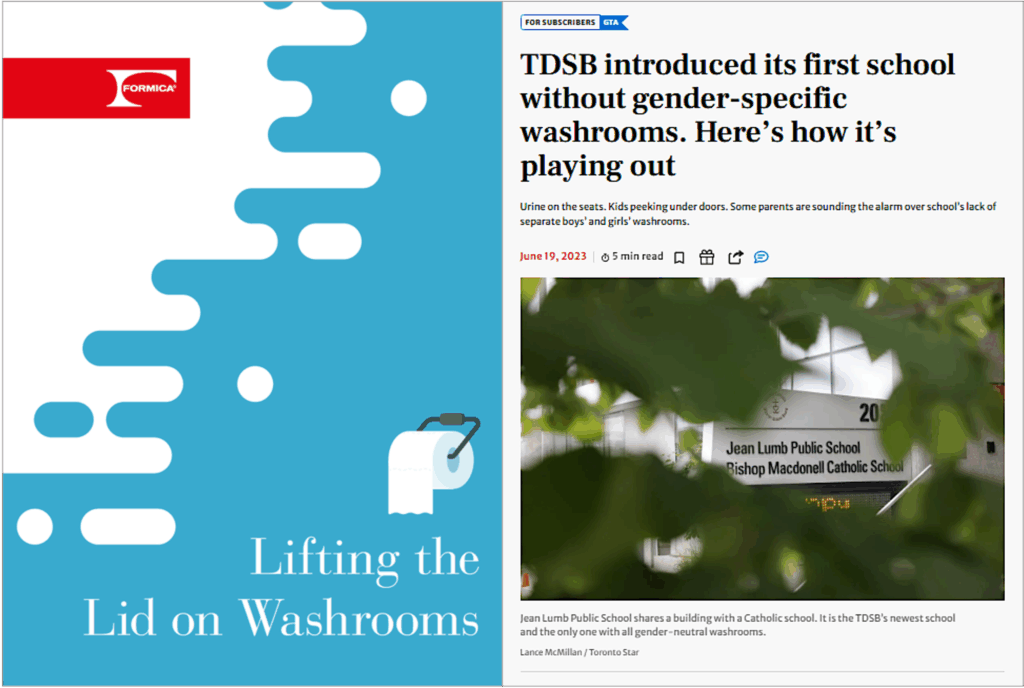

Here in Canada, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) in 2019 unveiled Jean Lumb Public School, its first school with no separate boys’ or girls’ bathrooms. “Universal washrooms honour all identities and gender expression” and offer “a safe and private space for all students,” TDSB trustee Alexis Dawson gushed to the Toronto Star. Yet the response from students and their parents was not acceptance, but a barrage of complaints regarding safety, privacy, bathroom hijinks and hygiene. As the Star reported, one mom said her Grade 1 daughter “comes home and requests to take a shower because the school toilet seats are dirty.” According to the paper’s investigative reporter, “boys are suspected of being the culprits.”

Seat up or down? In a 2017 poll by British bathroom fixture manufacturer Formica, two-thirds of women surveyed said they would rather not share a bathroom with men in a public building. When the Toronto District School Board opened Jean Lumb Public School in 2019, its first school with no gender-specific washrooms, many parents and students complained about habitually dirty toilet seats. An investigation by the Toronto Star concluded that “boys are suspected of being the culprits.”

Seat up or down? In a 2017 poll by British bathroom fixture manufacturer Formica, two-thirds of women surveyed said they would rather not share a bathroom with men in a public building. When the Toronto District School Board opened Jean Lumb Public School in 2019, its first school with no gender-specific washrooms, many parents and students complained about habitually dirty toilet seats. An investigation by the Toronto Star concluded that “boys are suspected of being the culprits.” Even potty-parity crusader Anthony admits there are problems when men and women use the same toilets. “Yes,” she says reluctantly, “there are a lot of women who do not like to use a toilet that a man has just used.” But, she says hopefully, “People will get used to it.” Besides, she notes, everyone uses the same washroom on airplanes and in hotel rooms. “There are places where you are forced to share. It can be done.”

What are the advantages of urinals? And why are they being removed to make way for gender-neutral washrooms?

The Pushback

Despite the confidence displayed by Anthony, Dawson and other proponents regarding the inevitability of genderless, urinal-less washrooms, other evidence suggests the unisex washroom may be more a passing fad than a permanent state of affairs. To whit, universal washrooms do not enjoy universal support.

While the gender-neutral washroom appears well-entrenched at Canadian universities, according to architect Joubert, the concept remains tenaciously unpopular off-campus. Given the amount of time her firm invested in creating its ‘Washrooms for All’ campaign, she’s been disappointed by the overall lack of interest.

As mentioned above, in 2019 Alberta’s NDP government unveiled new provincial guidelines for gender-neutral washrooms that mandated “urinals will not be provided in new builds” throughout the province. Later that year, however, the United Conservative Party swept to power and deep-sixed the entire initiative. According to Benji Smith, press secretary for current Minister of Infrastructure Martin Long, the old NDP design guideline “has been removed as it doesn’t align with the current Alberta Building Code or the Accessibility Design Guide.” As a result, designers and builders are again free to include urinals wherever and whenever appropriate. (And after C2C Journal inquired about the NDP document, it disappeared immediately from the provincial website.)

And while the gender-neutral washroom appears well entrenched at many Canadian universities, according to architect Joubert, the concept remains tenaciously unpopular off-campus. Given the amount of time her firm invested in creating its “Washrooms for All” campaign, she says she’s been disappointed by the overall lack of interest. “We always ask our clients if this is something they would be interested in,” she says. But so far no one other than UdeM has gone for it. Even the federal government regularly demurs on the idea, she says. “It has not been wildly popular,” deadpans Stephen Rotman, Figurr’s founding partner, in the same interview.

Even at the few non-university public facilities that have embraced the idea, the changes often prompt a backlash from patrons who prefer the old binary way of doing things. Noting that many females “are just not comfortable using gender neutral bathrooms,” theatre-goer Lynda Palmer organized a Charge.org petition in 2023 in response to Centre in the Square’s new washrooms. “The ratio of biological women frequenting this venue far outweighs the percentage of those identifying as gender neutral or the opposite gender, so why must they be the ones inconvenienced?” Palmer asked. Marketing director Randall declined to answer questions about the petition or the overall reaction to his building’s unisex washrooms.

At Jean Lumb Public School in Toronto, the Star’s initial investigation was prompted by the outcry of a group of 125 parents calling for a return to boys’ and girls’ washrooms. And as for the U.S. Navy’s gender-neutral heads, inventor Reichardt says “various ship board suppliers, who know ships and crew and engineers intimately through sales contacts,” have told him that a dramatic increase in water-usage has prompted internal regret about the decision to sail without urinals.

What are the problems with gender-neutral washrooms?

Many women report discomfort with shared washrooms, particularly regarding hygiene and privacy. According to a 2015 survey by Green Flush Restrooms, two-thirds of women preferred using women-only facilities, citing frustrations such as sitting on toilet seats that men have urinated on. One British survey found that 18 percent of women would “actually try to use the toilet less” if only unisex options were available.

At Jean Lumb Public School, which opened in 2019 and is first school in the Toronto District School Board to not have separate boys’ and girls’ bathrooms, many students and parents have complained about problems with hygiene, privacy and safety. One mother said her Grade 1 daughter “comes home and requests to take a shower because the school toilet seats are dirty.”

Equity versus Efficiency: The Final Reckoning

The ongoing and widespread pushback against unisex washrooms suggests the battle over urinals is far from over. And at the core of this bathroom controversy is a question that has dogged deep-thinkers for centuries: what price fairness?

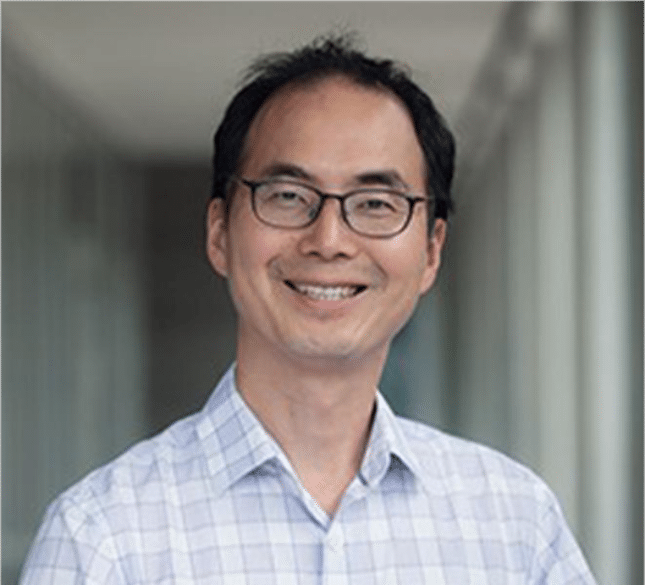

Tim Huh is a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business and holder of a prestigious Canada Research Chair in Operations Excellence and Business Analytics. His typical research milieu concerns the optimization of business systems such as call centres. But in 2019 he applied his analytic toolkit to the issue of universal bathrooms. Using data from a large soccer stadium in South Korea plus a range of existing washroom research, Huh and his co-authors set out to determine the best allocation of bathroom resources given society’s current preoccupation with gender equity.

The resulting article The potty parity problem: Towards gender equality at restrooms in business facilities in the academic journal Socio-Economic Planning Sciences wrestles with how to reduce waiting times for female customers considering typical business constraints. As Huh observes in an interview, the simplest solution is also the most dramatic. “Universal bathrooms are one way to equalize wait times,” he notes. “There are no equity issues if everyone has to wait in the same line.” If delivering identical waiting times for all customers is the only requirement, Huh observes, then it makes sense that every washroom should serve both men and women.

But, as we have already seen, such a solution means the end of the urinal and therefore imposes some large costs on society. “Urinals are very efficient,” Huh affirms. Further, while “people who want universal washrooms seem to express a stronger preference” than those who don’t, “many women do not want to use a bathroom with men.” In addition to the mess, these aversions include religious observance, privacy concerns and personal preference. Some women, as both Anthony and Joubert acknowledge, consider the washroom to be a female-only sanctuary where they can relax and chat with friends; having to share it with men destroys that ambiance.

Urinals save time, space and water. They’re cheaper to operate and easier to clean. And for reasons of hygiene, privacy, safety and personal preference many – perhaps most – women simply dislike the idea of sharing washrooms with men.

The fate of the urinal thus comes down to a trade-off between equity on the one hand and efficiency, as well as convenience, hygiene, culture and even aesthetics, on the other. Prioritizing sameness of waiting times by forcing everyone to use one washroom and thereby raisings the wait for men may meet the demands of relentless gender crusaders. But doing so comes at a higher cost across a wide variety of other metrics and social considerations.

Putting the equity versus efficiency conflict to the test, Huh’s research reveals the unsurprising outcome that a complete conversion to unisex washrooms improves female waiting times by lengthening the time men spend waiting. From the strict perspective of economic logic, Huh acknowledges, such an outcome violates Pareto optimality. This concept, named for 19th century Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, holds that for a change to be considered optimal, gains enjoyed by one party cannot come at the expense of another. Huh’s results further show that any wait-time improvement experienced by women will likely be far less significant than expected. This is because women must now compete with men for the same stalls, and those men will take longer to do their business in the absence of urinals. For these reasons, his paper concludes, simply converting existing washrooms to unisex operations “may not be a proper solution to ensure potty parity.”

Parity in waiting times can be achieved, or nearly so, Huh’s research finds, by retaining sex-segregated washrooms and raising the ratio of dedicated female to male facilities to 3:1. Another possibility, he says, is to provide male, female and unisex washrooms, which should mollify all but the most dogmatic gender activists while maintaining efficient operation from a plumbing perspective. Various combinations offer differing outcomes, Huh’s paper finds – but in no case does his research recommend an end to the men’s room or urinals. (It must also be recognized that in a world without urinals, many men will out of necessity find other places to go, harkening back to the smelly and unhygienic public situation that led to their invention in the first place.)

Urinals save time, space and water. They’re cheaper to operate and easier to clean. And women are unlikely to enjoy the results in their absence. For reasons of hygiene, privacy, safety and personal preference many – perhaps most – women simply dislike the idea of sharing washrooms with men. Mandating universal washrooms and getting rid of urinals will leave almost everybody and everything worse off. The battle between equity and efficiency is a walk-off win for efficiency.

Asked his own personal opinion on the matter, Huh replies plainly, “I would be sad if we got rid of urinals.” It’s hard to imagine any man disagreeing. Or nearly any woman, for that matter.

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior features editor at C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.