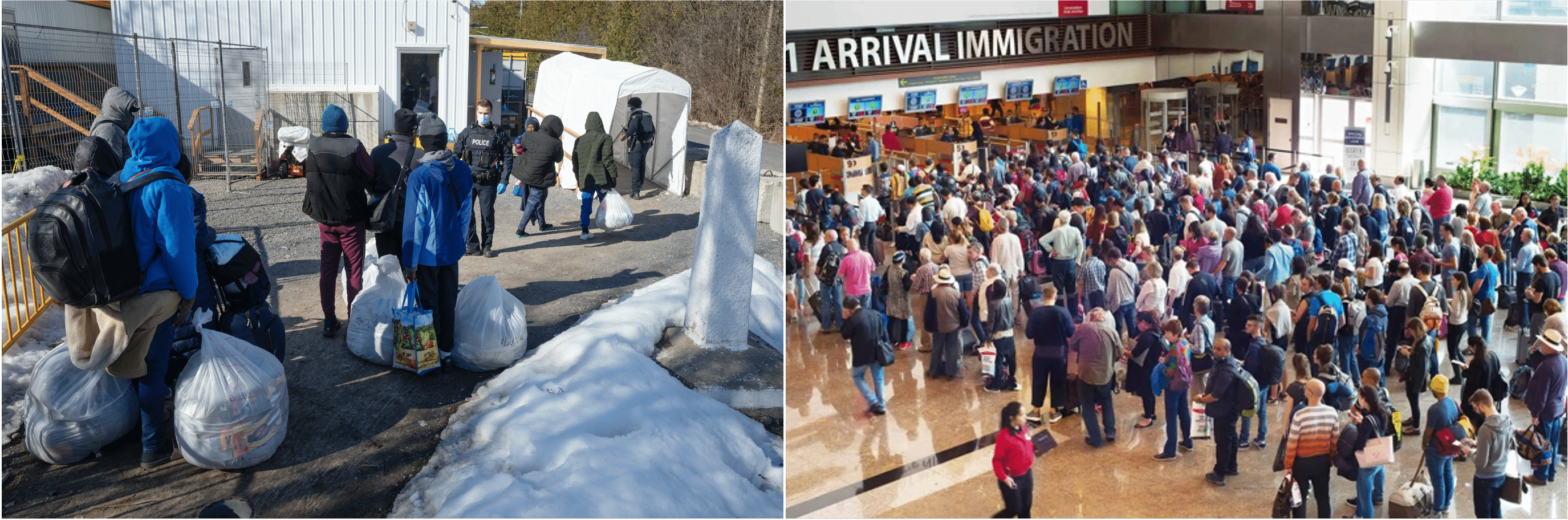

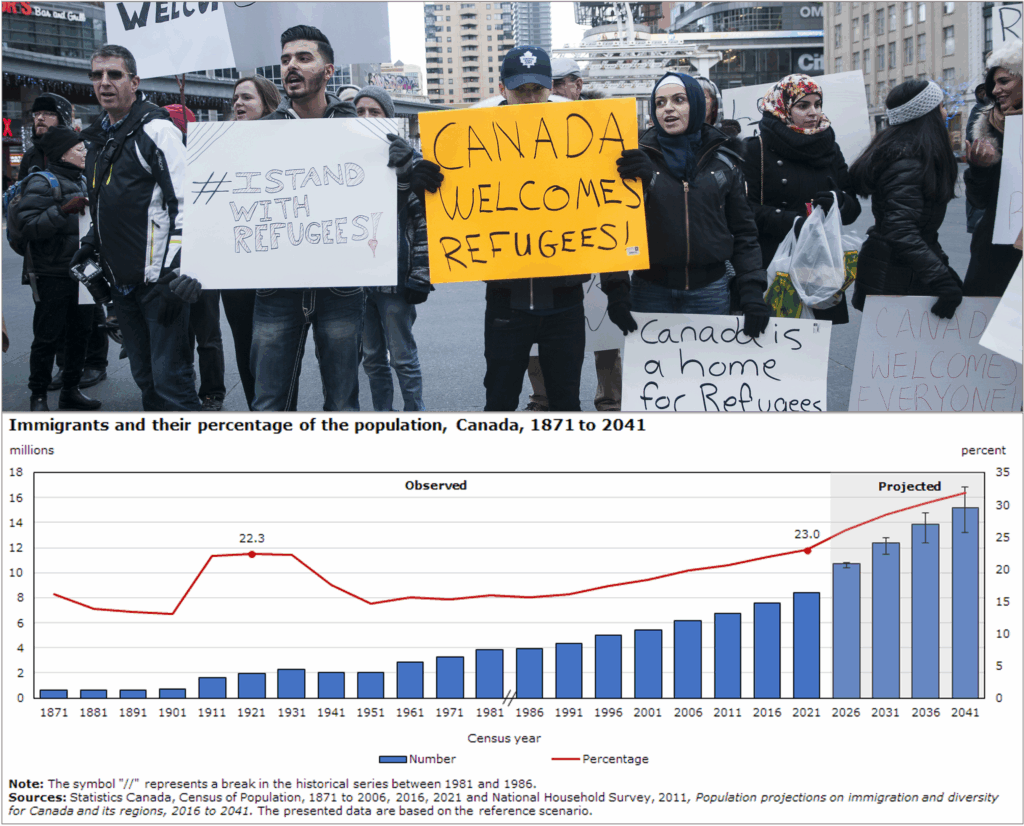

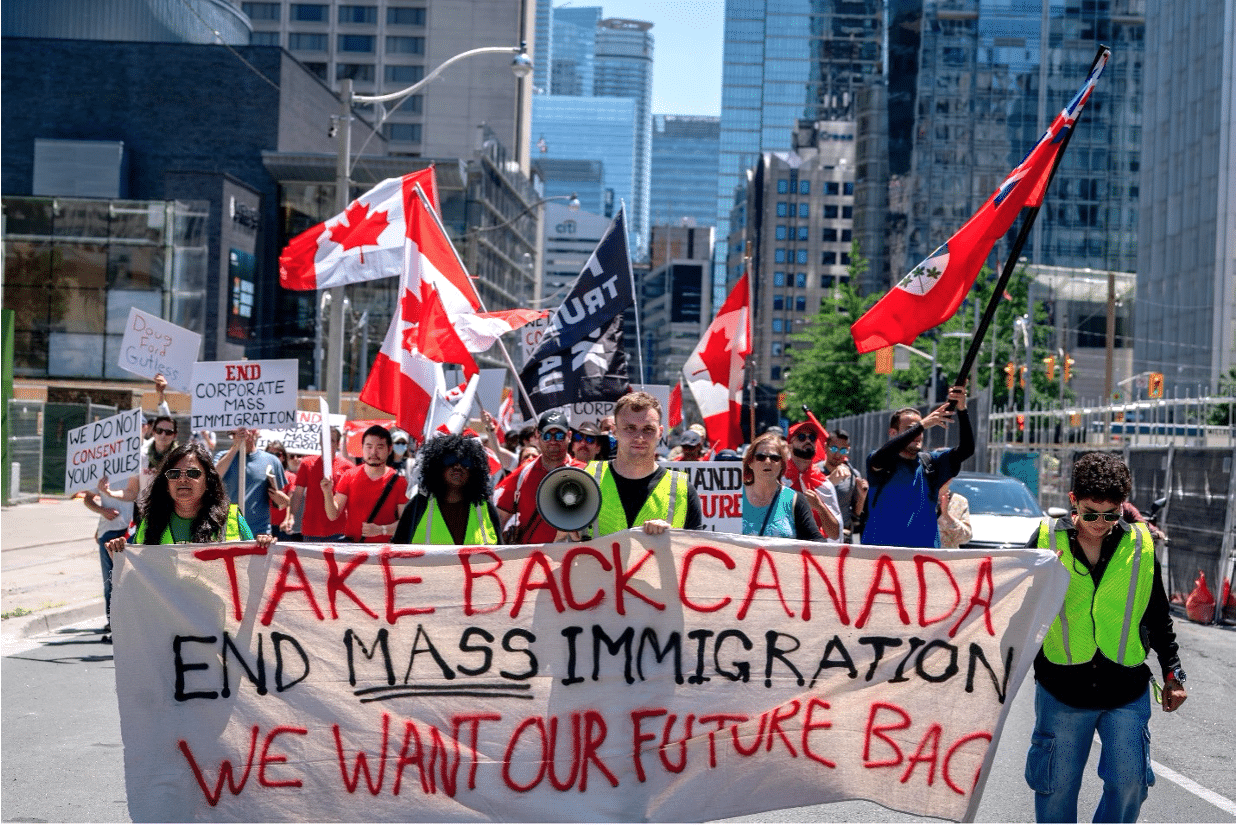

Canada is undergoing one of the most radical demographic experiments in the Western world. In 2023 the country admitted 1.25 million newcomers, the highest number in its history, pushing the total population over 40 million. Underscoring the scale of this transformation, immigration now accounts for 98 percent of Canada’s population growth. This is not a temporary surge but a deliberate government strategy that gathered momentum throughout the Justin Trudeau era. In response to mounting public pushback, his Liberal government last year issued a smokescreen of grandiose pronouncements that masked a meagre underlying promise to “stabilize” Canada’s population growth – while maintaining a target of 500,000 new permanent residents per year, plus nearly 700,000 temporary foreign workers, seasonal workers and international students.

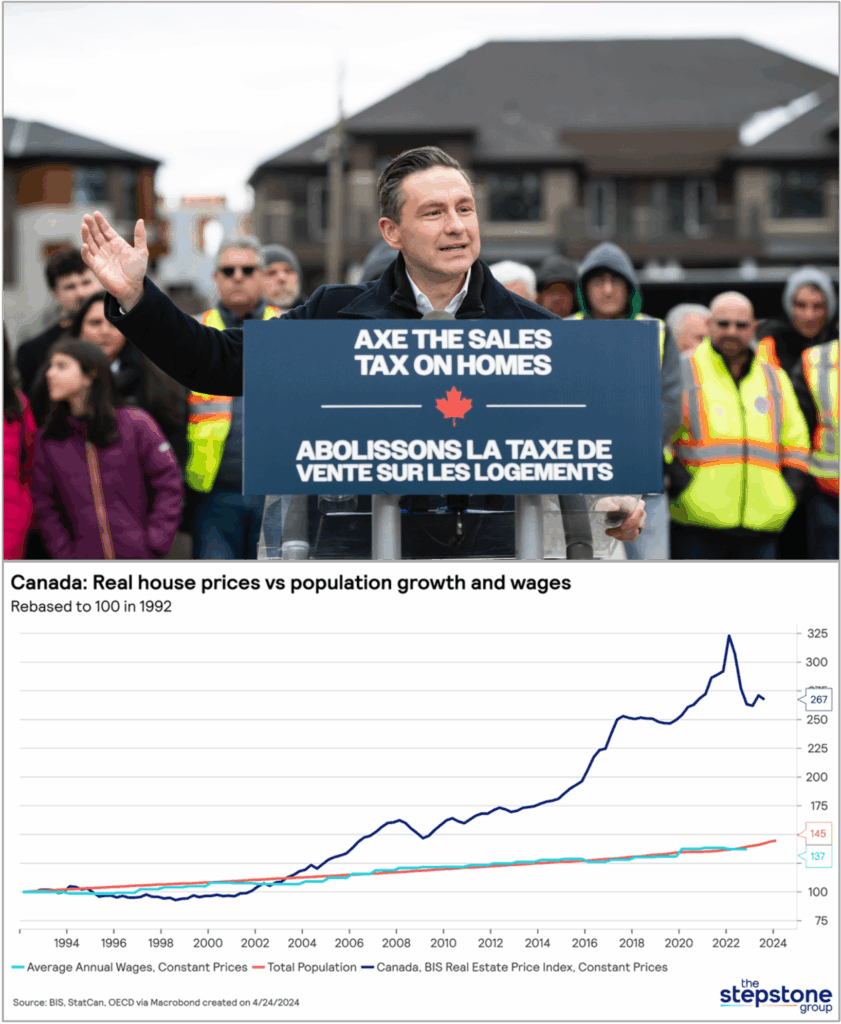

The negative consequences to life in Canada have been glaring. Housing grows ever-less affordable, particularly in major urban centres like Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, where surging demand gallops away from puny supply additions. The average cost of a home in Canada has soared past $700,000, effectively pricing out most young working families and first-time buyers. Even rental markets are being squeezed beyond sustainability, with vacancy rates in major cities hovering near historic lows. In Toronto, average rent for a one-bedroom apartment exceeds $2,500 per month. Healthcare systems, already strained, are buckling under the weight of rapid population growth, with waiting times for non-emergency surgery often stretching into years. Public infrastructure like roads, public transit and schools has not kept pace, eroding Canadians’ quality of life.

Economically the situation is equally troubling. While Canada’s GDP continues to (just barely) expand, this is driven entirely by increasing population. GDP per capita – a much more insightful measure of how a nation’s people are doing – has been declining for years. So even as the country’s headline economic figures are propped up by immigration, Canadians themselves are becoming poorer. As the Bank of Canada notes, this is linked to stagnation in labour productivity, largely caused by declining capital investment but exacerbated by an influx of low-wage workers in sectors like retail and hospitality. Meanwhile, inflation continues to erode purchasing power and the cost-of-living crisis plagues millions. And then there is continuing urban decay and surging crime, exacerbated by Canada’s ever-lighter vetting of incoming migrants – including from hotbeds of terrorism like Gaza.

Political acknowledgement of immigration’s role in these problems remains decidedly muted. Federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre campaigned vigorously during the recent election campaign on inflation, housing costs and the decline in Canada’s standard of living. His rhetoric doubtlessly resonated with a working-age middle class and younger voters who feel abandoned by elites. Yet on the immigration file, Poilievre tiptoed as if picking his way through a minefield. The party’s campaign platform acknowledged the housing crisis but avoided directly linking it to immigration levels. Instead, Poilievre focused on bureaucratic inefficiencies and tax policies, sidestepping one of the root issues. Why?

The answer, I suggest, is not merely political but philosophical. Among Canadian elites – on both the left and the right – immigration has become a kind of secular virtue, an unquestioned good that transcends debate. To question it, even modestly, is to risk moral excommunication. Canadians have been fed the mantra that “diversity is our strength.” The progressive left frames any critique as racism, xenophobia or white nationalism; the corporate right views immigration as a driver of economic growth and disregards its social costs. Even many conservatives, while eager to pose as defenders of the forgotten Canadian middle class, are hesitant to challenge the dogma that the more open we are to the world, the more virtuous we become.

This silence betrays a deeper unease – an ambient confusion, even a kind of moral embarrassment – about what a nation truly is and what it means to belong to one. It reflects a reluctance to articulate, let alone defend, the idea that national identity entails more than administrative citizenship, that it carries with it bonds of memory, mutual obligation and shared destiny. It also reflects a failure to confront the moral and philosophical foundations of national identity. To understand this crisis, for that is what I believe it is, we must turn to the roots of our predicament – not in policy papers or economic data – but in the competing visions of human belonging that shape our politics.

The Ascent of Liberal Universalism

At the heart of the immigration debate lie two contrasting visions of the moral order: one universalist, liberal and abstract, the other particularist, conservative and rooted. These visions are not merely academic; they influence how we think about obligation, community and the purpose of the nation-state.

The liberal universalist vision (which can also be described as cosmopolitan or globalist) is dominant in Canada’s elite institutions: universities, media, government, NGOs and many corporations. It views human beings primarily as bearers of rights and consumers of things, detached from place, history or culture. From this perspective, compassion must be borderless and justice requires an impartial and equal concern for all persons, regardless of citizenship or proximity. In this view, the nation is little more than a legal construct, a container for administering universal principles; certainly, it is something less than entirely sovereign.

It is not hard to see how such an outlook renders preferring one’s own countrymen over strangers morally suspect, a form of chauvinism, a jarring and almost bizarre double-standard. This worldview underpins much of Canada’s recent immigration policy, one that has increasingly prioritized global humanitarian commitments over the country’s economic, social and security needs. This is why Trudeau’s government framed high immigration levels as a moral imperative, a way for our “post-national state” to “do our part” on the world stage.

Beneath this policy framework lies a profound metaphysical conviction, one rarely articulated but widely assumed. It conflates the universality of human dignity (a Christian concept, one that I consider both legitimate and central to the Western conception of humanity) with the feeling that it therefore follows that people are abstract and interchangeable – detached from the specificities of history, culture and community.

Liberalism, which began as a promise of freedom, ends by exiling the soul from any true homeland. It liberates but leaves us orphaned. It advances a morality based on what might be called ‘a view from nowhere’.

Rooted in Enlightenment-era universalism, this view regards the individual as existing prior to and independent of all cultural, historical, or communal ties. From this abstraction, liberalism determines that distinctions of nation, kinship and cultural inheritance are at best arbitrary and, more often, unjust. Love of one’s own is no longer regarded as a natural and noble form of human attachment, but as a moral defect that requires correction.

This view has become the prevailing orthodoxy of our moral and political order. To enforce it, liberal societies have erected vast and intricate legal, bureaucratic and pedagogical systems designed not only to protect individuals but also to refashion them. Human rights commissions, diversity protocols and equity audits do not merely arbitrate justice; they train citizens to adopt and internalize a particular, deracinated, abstract moral posture. In so doing, they sever moral reasoning from personal experience and undermine the natural bonds of place, tradition and belonging.

What remains is a self unmoored from history and home, obliged to treat all equally – and, thus, no one intimately. The natural moral order, what St. Augustine named the ordo amoris or “order of love”, is inverted. Love of one’s own is rebranded as bias; belonging is redefined as exclusion. Liberalism, which began as a promise of freedom, ends by exiling the soul from any true homeland. It liberates but leaves us orphaned. It advances a morality based on what might be called “a view from nowhere”.

How is mass immigration reshaping Canadian citizenship?

The Conservative Alternative

In contrast, the conservative-communitarian tradition asserts that we are not disembodied agents of reason; we are beings shaped by particular loyalties, customs and traditions. Accordingly, love and obligation flow outward from the near to the far: from family to neighbour to nation to humanity. We develop our caring for the wider world not by negating these natural loyalties but by affirming them. The love of one’s own is not a moral failure; it is the seedbed of all moral development. This perspective views the nation not as an arbitrary and ultimately dispensable construct but as a moral community, bound by shared history, culture and mutual obligations.

The late British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton coined the term oikophilia – Greek for “love of home” – as a counterpoint to the left’s use of “xenophobia” to discredit anyone who questioned open borders. (Source of photo: fronteirasweb, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

The late British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton coined the term oikophilia – Greek for “love of home” – as a counterpoint to the left’s use of “xenophobia” to discredit anyone who questioned open borders. (Source of photo: fronteirasweb, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)Sir Roger Scruton, the late British philosopher and one of the most eloquent defenders of this tradition, understood the tension and explored it with clarity and grace. To advance the conservative argument, he coined the term oikophilia from two Greek roots: oikos, meaning home, and philia, meaning love. Scruton thereby articulated a moral intuition often dismissed in modern discourse: that attachment to one’s own is not a form of exclusionary sentiment or pathological nostalgia, but rather the essential foundation of social cohesion and political order. Oikophilia deftly rebuked the left’s casual slur of “xenophobia” aimed at anyone who questions unlimited immigration, vast intake of refugees and unvetted migrants, or crime patterns among unassimilated newcomers.

“The nation-state,” Scruton wrote, “is not a machine for achieving social justice, or a contract for mutual advantage. It is a home – a place that is ours, the foundation of our trust, the source of our sense of belonging.” In another essay, he put the matter even more plainly: “If we owe obligations to humanity, it is because we already owe obligations to those close to us, from whom our understanding of obligation derives.” For Scruton, the liberal vision, for all its professed concern with justice, is unable to deliver. “The abstract rights of man,” he once remarked, “are a poor substitute for the concrete duties of citizenship.”

By attempting to leap over the intermediate structures – family, religion and nation – universalism hollows out the vital forms of human attachment and leaves a bloodless husk. It is an ethic professing to love humanity in general while ignoring or scorning the concrete demands of neighbourly life. As G.K. Chesterton mordantly observed in his poem The World State:

The villas and the chapels where

I learned with little labour

The way to love my fellow-man

And hate my next-door neighbour.

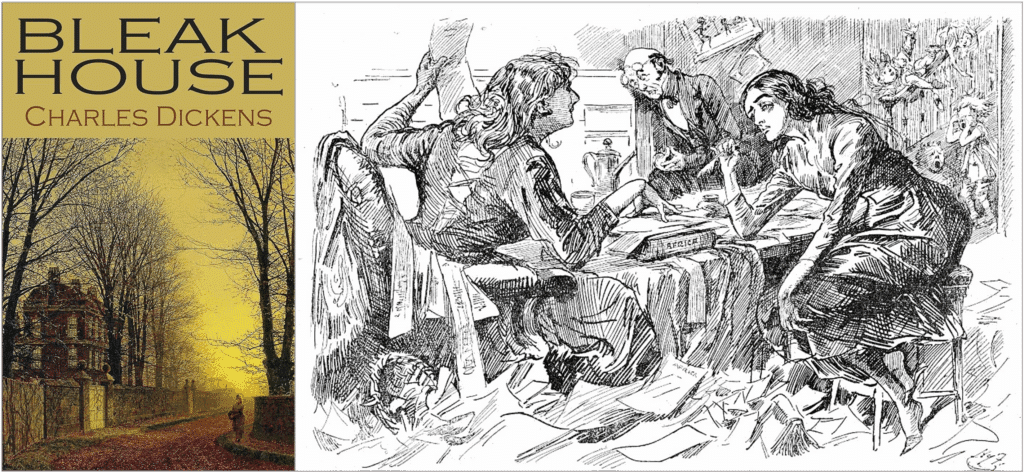

Charles Dickens made a similar point in his novel Bleak House through the satirical Mrs. Jellyby, whose “telescopic philanthropy” extended compassion to the distant peoples of Africa while her own children and neighbours languished in neglect.

This concept of an order of love, rooted in the thought of Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas and Aristotle, maintains that moral obligation is not uniform but graded by proximity. It does not license xenophobia; instead, it acknowledges the finitude of human caring and the situatedness of the human person. Humans are not deracinated, abstract agents, but creatures embedded in families, communities and nations. This view, one that I share, holds that it is natural – even morally necessary – that we care most deeply for those closest to us.

What does the Canadian immigration policy update reveal about the political and moral priorities of Canada’s governing elites?

A Comeback for the “Order of Love” and “Located Beings”?

J.D. Vance, the new American Vice President, has been giving political expression to this classical and Christian insight. In his bombshell speech at the Munich Security Conference in February, Vance argued that, “A country that does not prioritize the well-being of its own citizens is not a moral country. It is a failed country.” In another interview, Vance offered the at-once blunt and morally lucid opinion that, “Your compassion belongs first to your fellow citizens. That doesn’t mean you hate people from outside your borders, but there’s an old-school concept…that you love your neighbor as yourself.”

Cosmopolitan advocates like Stewart appeal to the abstract duties of global citizenship, whereas Vance stands firmly within the older tradition of moral realism, which begins with his natural affections as a husband and father, extends through the bonds of community, and culminates in the love of country.

Just as a father who treated his own children no differently from complete strangers would be rightly judged morally derelict, so too should be a nation that fails to prioritize the good of its own people. Vance’s Munich speech emphasized the primacy of national cohesion and the duty to care for one’s own. To love rightly, Vance argues, is not to love indiscriminately, in some flattened, universalist fashion, but to acknowledge a hierarchy of moral obligation grounded in closeness, kinship and civic belonging.

This affirmation of graded moral obligation elicited a swift rebuke from cosmopolitan quarters, most notably former UK MP Rory Stewart, who on his popular podcast “The Rest is Politics” dismissed Vance’s remarks as a retreat into parochialism. Yet in doing so, Stewart laid bare the sentimental confusion at the heart of liberal cosmopolitanism: it mistakes the universality of fundamental human dignity for the erasure of particular loyalties. Stewart appeals to the abstract duties of global citizenship, whereas Vance stands firmly within the older tradition of moral realism, which begins with his natural affections as a husband and father, extends through the bonds of community, and culminates in the love of country.

The contrast is telling. Canadians have long struggled to reconcile their humanitarian impulses with their responsibilities as stewards of a unique, historical political community. We pride ourselves on our kindness, openness and soft-power decency, but these virtues become vices when they are severed from the rootedness of civic love and extend outward in all directions. The ordo amoris may jar polite Canadian ears, trained and subdued by decades of multicultural idealism. Still, it names a truth we neglect at our peril: that moral seriousness begins with loyalty, with loving rightly those who are ours to love. To invert that order is not compassion, it is dereliction.

Though not a conservative, the distinguished British philosopher Bernard Williams recognized the limits of cosmopolitan abstraction. In his 1985 book, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, Williams reminded us that any credible moral philosophy must contend with the concrete realities of human attachment. He was deeply skeptical of the ideal of a universal moral law propounded by 19th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, which seeks to untether ethical obligation from the particularities of personal relationships. Such an ideal, Williams argued, places an impossible demand on moral agents, one that overlooks the densely woven ties that bind us to those we love. To ask a father to regard his child and a stranger with equal concern is, for Williams, not the apotheosis of rational ethics but a fundamental misunderstanding of human nature.

“We are not agents of pure reason, detached from circumstance,” Williams wrote in his essay The Idea of Equality, cautioning against the Kantian ideal. “Our commitments are lived, not theorized.” And in his book Moral Luck, he issued a sobering warning against “the tyranny of abstract principles” that fail to account for the embodied and embedded nature of moral life. “If morality is to make sense,” Williams wrote, “it must begin from where we are. We are located beings, and our obligations are shaped by that fact.”

David Stove, the Australian philosopher known for his acerbic wit, was even more blunt. “There is something pathological,” he wrote in “What Is Wrong With Our Thoughts?”, “in the belief that a man has no more right to prefer his own family or country than he does a stranger. This is not morality; it is moral derangement.” In On Enlightenment, Stove argued that abstract moral universalism frequently leads to absurd, even harmful, conclusions: “A man who says he has no more love for his countrymen than for a stranger is either lying, or a man from whom no help will come.”

What are the impacts of mass immigration on Canadians’ quality of life?

Canada’s Crisis of Meaning

Scruton, Vance, Williams and Stove offer a much-needed corrective to the moral confusion that pervades Canada’s immigration debate. They remind us that a nation is not a moral abstraction to be administered by technocrats, nor a blank canvas upon which to project fashionable ideals of universal justice. It is, instead, a concrete inheritance – a web of affections, memories and obligations – into which we are born or invited and to which we owe fidelity. A healthy polity depends not on the erasure of boundaries but on their moral intelligibility. Only within the thick texture of family, neighbourhood, language, tradition and the other elements collectively making up community life do our ethical duties take on substance and meaning.

Canada’s immigration crisis is, ultimately, a crisis of meaning. The liberal vision imagines a world of rights-bearing individuals, untethered from history or place, free to roam wherever they will and with as much claim upon their destination as the locals. But real nations are not weightless constructs. They are moral communities.

Prioritizing the needs of distant strangers – recall the “telescopic philanthropy” of Dickens’ Mrs. Jellyby – over those of one’s fellow citizens is not, as our political class would have it, the peak of moral enlightenment; rather, it is the abdication of the responsibilities that make moral life possible. Such a stance reflects not compassion and generosity but forgetfulness: forgetfulness of the fragile bonds that sustain our civic life and the quiet duties we owe one another. In the name of unlimited kindness, we risk dissolving the forms of life that make kindness more than sentiment. At stake is more than simply a policy debate, but a philosophical one: What does it mean to belong? What do we owe, and to whom? If the answer is to be serious, it must begin in the ordered loves that bind us to home, history and each other.

Canada’s immigration crisis is, ultimately, a crisis of meaning. The liberal vision imagines a world of rights-bearing individuals, untethered from history or place, free to roam wherever they will and with as much claim upon their destination as the locals. But real nations are not weightless constructs. They are moral communities. Canada must rediscover the ethical grammar that views obligation not as descending from metaphysical abstraction but beginning with the individual and radiating outward. It must affirm that to love one’s own is not to hate or ignore the other, but to honour the structure of human affection and duty. This is not a call for exclusion, but for rootedness; not for parochialism, but for prudence.

Canada’s globalist supporters have grown frustrated with the increasing discontent of Canadians who perceive that relentless immigration is increasingly unravelling the nation’s cohesion. Although this unrest is real, it should not be read as a rejection of compassion but as a plea to restore a moral order that values the immediate bonds of community and country over the abstract claims of universalism. Canada faces a defining choice: continue eroding its identity for a borderless vision or reaffirm the deep loves that sustain a moral community. Only by grounding itself in these concrete affections can Canada maintain its humanity and act with true justice in a divided world.

Patrick Keeney is a Canadian writer who divides his time between Kelowna, B.C. and Thailand.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.