“I am a Canadian, a free Canadian, free to speak without fear, free to worship God in my own way, free to stand for what I think right, free to oppose what I believe wrong, free to choose who shall govern my country. This heritage of freedom I pledge to uphold for myself, and all mankind.”

—John Diefenbaker, Dominion Day, 1960

As historical figures fade from living memory, what we come to believe about them – if we care about truth – ultimately relies on accurate histories. This is one strength of Freedom Fighter: John Diefenbaker’s Battle for Canadian Liberties and Independence, Bob Plamondon’s biography recently published by the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy.

It is particularly important in the case of Diefenbaker, whose legacy had been stained, seemingly forever, by Peter C. Newman’s biography Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years. An Austro-Czech émigré, Newman became a fixture of Canada’s literary scene as a journalistic gadfly and prolific author hungry for controversy. His 1963 opus, released while Diefenbaker was still Progressive Conservative leader, portrayed the former prime minister as a quixotic loner – “a mysterious mixture of vanity and charm, vulnerability and brass, outrage and mischief.” Another biographer, Denis Smith in Rogue Tory: The Life and Legend of John G. Diefenbaker, described his subject as “a man outside of time and place in late-twentieth century Ottawa.” Accordingly, in his back-cover blurb endorsing Freedom Fighter, journalist Jeffrey Simpson calls the book “revisionist” in outlook.

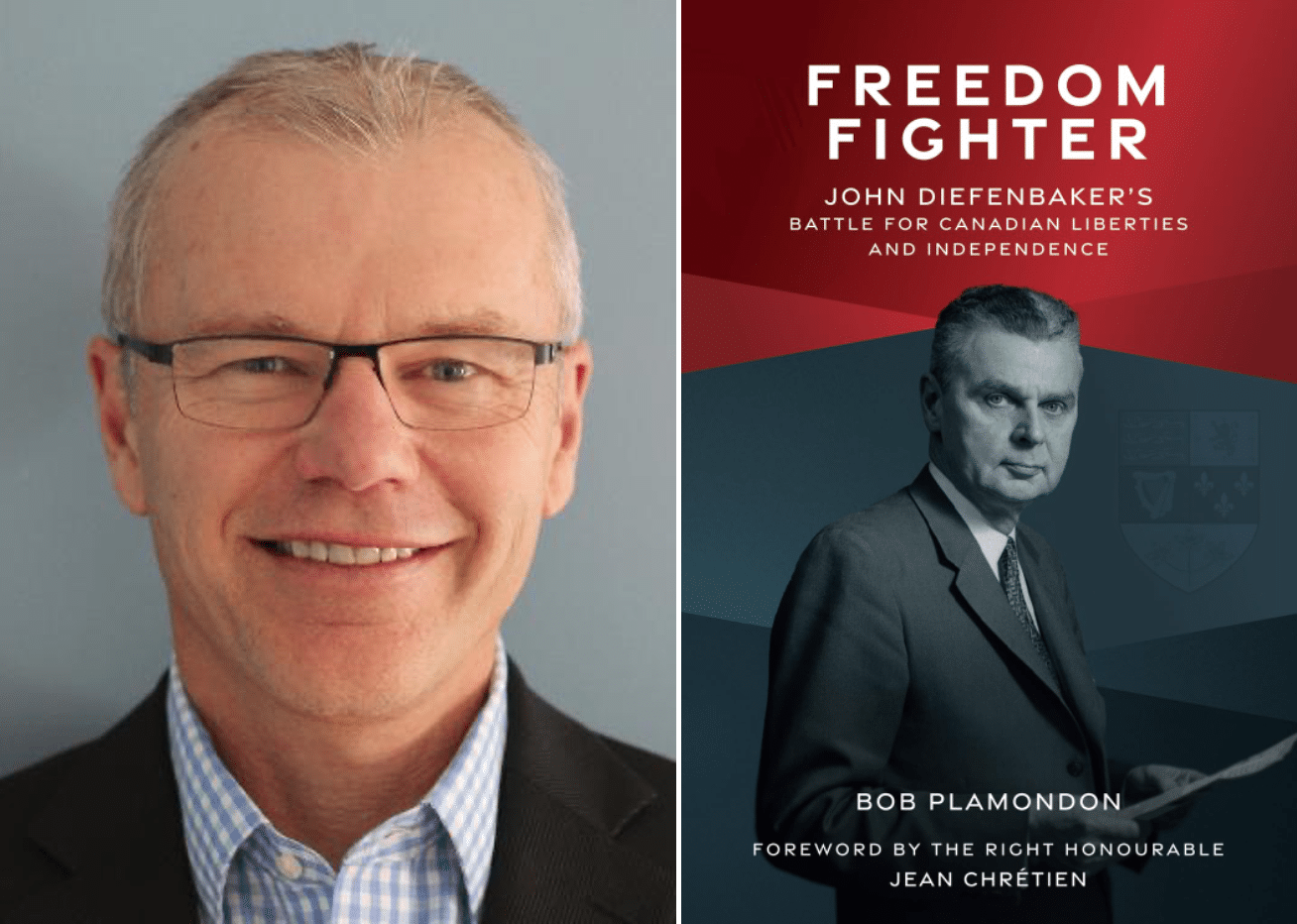

“Revisionist” in outlook: Bob Plamondon’s (left) recent book Freedom Fighter: John Diefenbaker’s Battle for Canadian Liberties and Independence stands out among similar literature as a commendable attempt to objectively examine Diefenbaker’s legacy, his political life and historical significance.

“Revisionist” in outlook: Bob Plamondon’s (left) recent book Freedom Fighter: John Diefenbaker’s Battle for Canadian Liberties and Independence stands out among similar literature as a commendable attempt to objectively examine Diefenbaker’s legacy, his political life and historical significance. But Plamondon’s effort is only revisionist in the sense that it avoids adjectives like “renegade” and “rogue”, declining to portray Diefenbaker as a mere purveyor of populism, and seeking instead to judge his legacy and place him objectively into history. In this Plamondon is convincingly successful. While not showcasing Dief’s flaws, the book makes no secret of them, calling the PC leader “a stubborn loner…[insecure]…about his position with eastern-based power brokers within the Progressive Conservative party.” The book avoids duplicating much of the personal side of Diefenbaker showcased in The Duel: Diefenbaker, Pearson and the Making of Modern Canada, John Ibbitson’s recent tandem-biography of Dief and his Liberal nemesis, Lester Pearson. Freedom Fighter concentrates on Diefenbaker’s political life and historical significance with little said, for example, about the Chief’s two marriages.

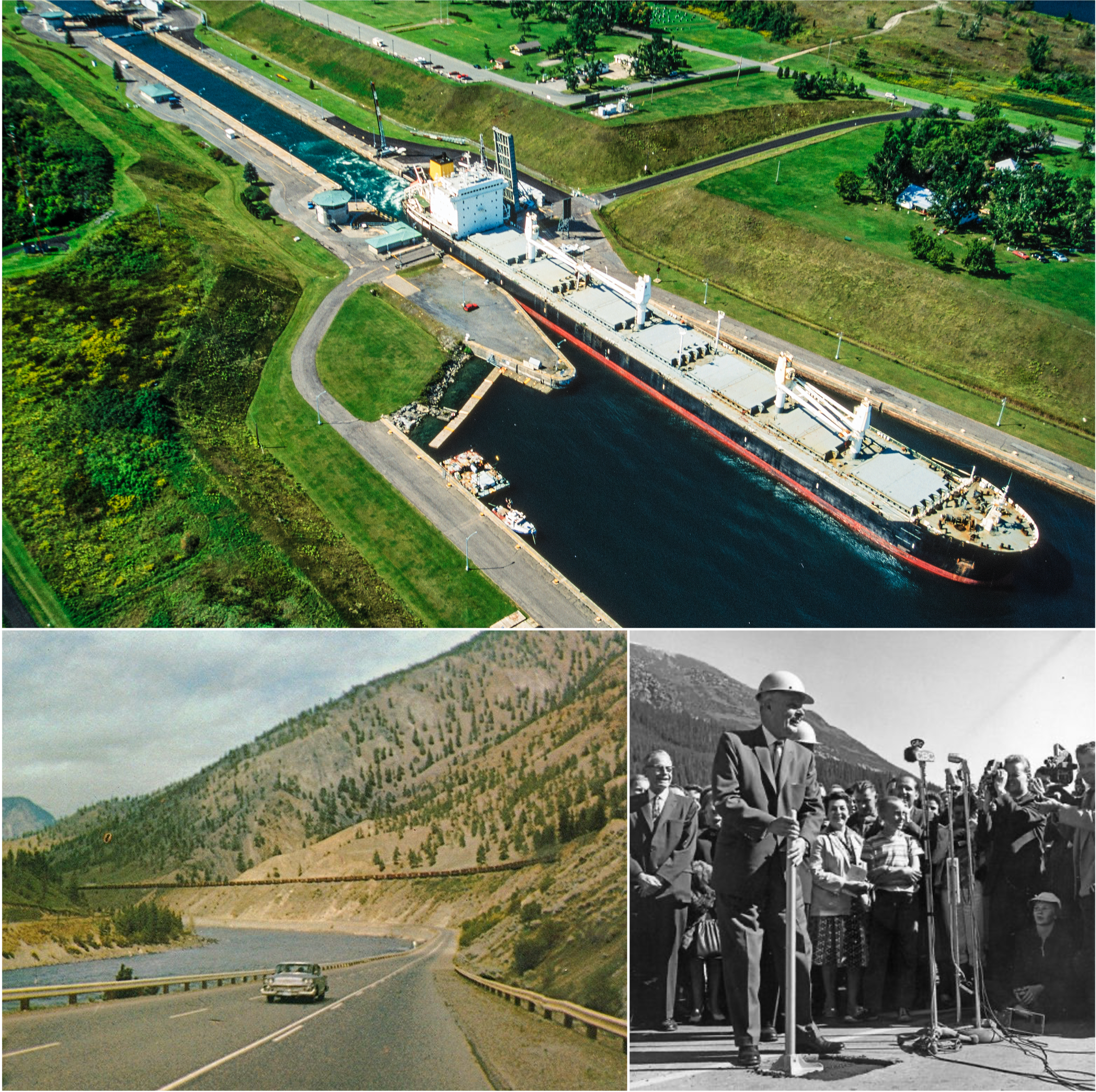

Plamondon ranks Diefenbaker as a consequential prime minister, one who oversaw continued economic growth, completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Trans-Canada Highway, and significant domestic policy reforms. “Diefenbaker has a record of accomplishment,” Plamondon states in words that would surely have stuck in Newman’s craw. “None of the major reforms and policies he implemented as prime minister were reversed by his successors. Indeed, all subsequent prime ministers expanded upon his progress in social policy and protecting individual liberties. There is no doubt on the facts that he was a successful politician and prime minister.”

Plamondon, an economist and writer based in Ottawa, has penned political-historical biographies, notably on Jean Chretien (2017), a scorching volume on Pierre Trudeau (2013) and two books on Canadian conservative politics – Full Circle (2006) and Blue Thunder (2009). Freedom Fighter is a worthy addition to this group, an engaging popular history sprinkled with informative photos of the protagonist. The content is arranged more-or-less chronologically, with individual chapters devoted to specific themes, such as First Nations, the Canadian Bill of Rights, Canada-U.S. relations, and others. Despite relying on a solid breadth of footnoted, mainly secondary sources, the book’s easy flow makes it accessible to any interested reader.

Diefenbaker’s early career was marked by two things. These were, first, his humane approach to the law, where he routinely represented poor farmers, natives and conspicuously unsavoury characters, often overcoming long odds to win their cases. Second was his dogged pursuit of a political career.

Full disclosure: I consider Plamondon a friend, grew up in a family of Diefenbaker supporters and once even skipped school to meet “the Chief” at a book-signing in Montreal. This should not cause the reader to question the merits of Plamondon’s account.

How has the legacy of John Diefenbaker been controversial or misrepresented?

The legacy of John Diefenbaker, a Saskatchewan-raised lawyer and Progressive Conservative politician who in 1957 became Canada’s 13th prime minister, was long overshadowed by Peter C. Newman’s biography Renegade in Power, which portrayed Diefenbaker as “a mysterious mixture of vanity and charm, vulnerability and brass, outrage and mischief.” His reputation was further shaped by narratives that painted him as “a man outside of time and place.” However, the more balanced assessment provided in Freedom Fighter: John Diefenbaker’s Battle for Canadian Liberties and Independence, a 2025 biography by Bob Plamondon, shows that Diefenbaker was a consequential prime minister with enduring policy achievements.

The Tyranny of the Present

Our 13th prime minister was born in rural Neustadt, Ontario in 1895, the son of William Diefenbaker, a teacher, and Mary (née Bannerman), a homemaker. The family moved to Saskatchewan when John was 8 – just before the creation of the province – which at the time was on Canada’s raw frontier. Between the completion of the transcontinental railway in 1885 and the First World War, over 3 million people migrated west, many of them immigrants from central and eastern Europe, creating an environment at once exciting and tumultuous for the Diefenbakers.

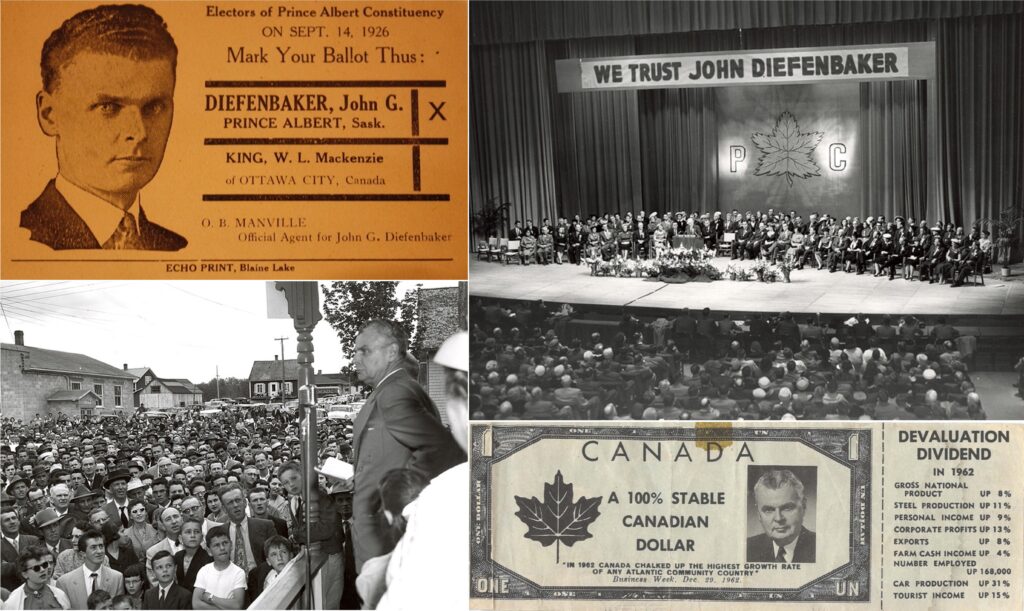

After graduating from the University of Saskatchewan, he set up a law practice northwest of Saskatoon, ultimately moving it to Prince Albert. Diefenbaker’s early career, as described by Plamondon, was marked by two things. These were, first, his humane approach to the law, where he routinely represented poor farmers, natives and conspicuously unsavoury characters, often overcoming long odds to win their cases. Second was his dogged pursuit of a political career. Diefenbaker ran repeatedly for office – mostly without success. As noted in the book, he lost “five municipal, provincial and federal elections between 1925 and 1940.” He also twice ran unsuccessfully for the PC leadership before finally winning in 1956.

The very next year “Dief” – or “the Chief”, as he was known since he became leader (also because he was honorary chief of several Indigenous bands) – was thrust into power due to Liberal mishandling of the trans-Canada natural gas pipeline project. He parlayed his minority government into a landslide majority the following year, displaying the incomparable campaign skills that made him a political legend. Before “Trudeaumania” there was the Diefenbaker sweep.

One great conceit of our society is recency bias, wherein past figures are judged by today’s – ostensibly superior – sensibilities. Denis Smith’s assessment that Diefenbaker was somehow “outside of [his] time” reflects this essentially progressive view: that his ideas and style were somehow antiquated and not as “advanced” as his contemporaries positioned on the inevitable arc of history.

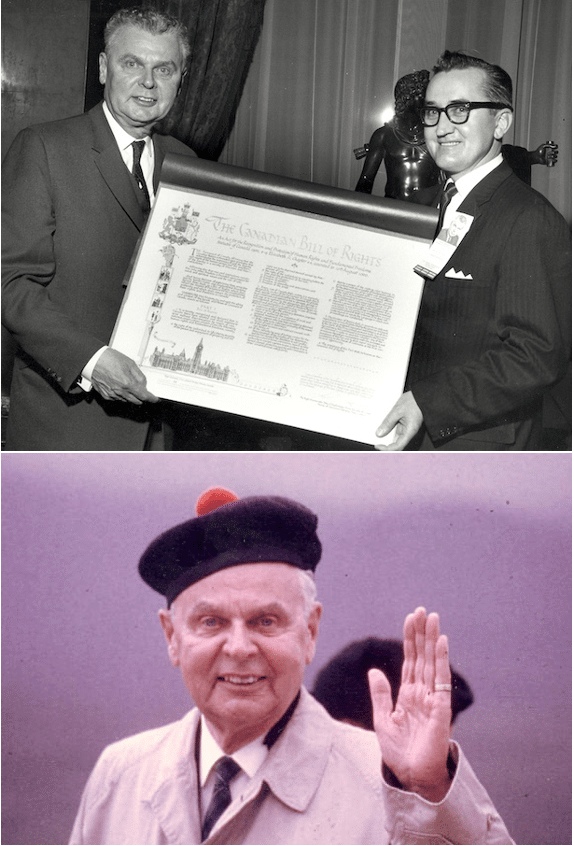

Though largely avoiding this, Plamondon occasionally falls into defending Diefenbaker by applying the standards of today, instead of sticking strictly to good historical practice and always evaluating Diefenbaker in the context of his era and his society. Dief strengthened Indigenous rights, he appointed women, he promoted and passed the Canadian Bill of Rights. These are all true, and were unusual for his time. But they are admirable more – and mainly – for their intrinsic value rather than because they’d appeal to the modern reader or gain a nod from a left-wing academic.

Plamondon attributes Diefenbaker’s visceral sympathy for “the little guy” to his experience growing up with a German surname in the culturally still very British Canada. “Diefenbaker was animated by his experience as someone of German heritage,” Plamondon writes, “and it gave him sympathy for Canadians not part of the conception of Canada as a union of two founding peoples, French and English.” In Dief’s own words, “It distressed me that those who were neither English nor French in origin were not treated with the regard that non-discrimination demands.”

Despite his father William having been born in Canada, when Dief ran in the 1925 federal election campaign he was still called a “Hun” (which young readers today may not even know was a pejorative for German in those days). In reply he admitted at one campaign event that his grandmothers spoke no English, only Scot’s Gaelic, and asked, if there was no hope of him becoming Canadian, “Who is there hope for?”

Diefenbaker was already a formidable orator, a skill he’d honed from his school days. He was also very funny, although his humour is harder to appreciate nowadays, accompanied as it was by shaking jowls and fingers stabbing the air. Such as when he roasted newly elected Liberal leader Lester Pearson in the Commons over his fear of going to the polls: “On Thursday there was shrieking defiance, on Monday there was shrinking indecision.” One of Dief’s best routines concerned the scandal over Lucien Rivard, a notorious career gangster who had escaped captivity on the Liberal government’s watch by wangling permission to water his prison’s outdoor skating rink on a noticeably warm March day. As the scandal unfolded, Dief would wind himself up and exclaim, “You know, it was on an evening much like this that Lucien Rivard was sent out to flood the prison rink…!”

“He helped us…when no one else would”

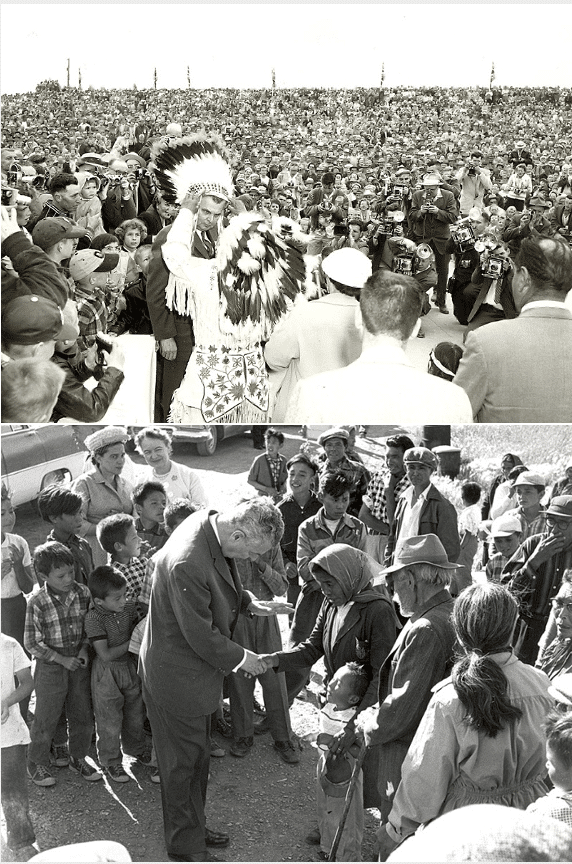

Freedom Fighter devotes a chapter to Diefenbaker’s relationship with Indigenous Canadians, known then simply as Indians. Indigenous rights were of lifelong importance to him. As a young practising lawyer prior to his political career, he stood up for treaty rights as well as representing native defendants in court. Quotes from Métis author Maria Campbell provide moving testimony of his devotion to these communities. “He helped us,” Campbell wrote, “and the important thing was that he did so when no one else would.”

All Dief’s achievements would likely pass muster with our latter-day moral arbiters, who have so far refrained from cancelling Diefenbaker as they’ve done with Sir John A. MacDonald, Egerton Ryerson and others. This part of the Chief’s legacy speaks more to his upholding enduring values than to what might be fashionable today.

The Chief routinely praised First Nations for volunteering to fight for Canada in the Second World War when they had no obligation to do so. As Plamondon writes, he rose in the House of Commons during a 1944 debate on recruitment, singling out “an Indian by the name of Arcand, a man denied citizenship, who has nine sons in the armed forces.” He also spoke frequently of how Indigenous Canadians, then unable to vote in elections, were denied legal rights, particularly in seeking recourse against Crown decisions that affected them.

Were one to round out his postmodern bona fides, the fact that he appointed the first native Canadian Senator, Chief James Gladstone of southern Alberta’s Blood Tribe, would serve. It was of course also Progressive Conservative legislation that gave natives the right to vote in 1960. And Diefenbaker named the first female to the federal Cabinet, Ellen Fairclough, who served as Minister of Citizenship and Immigration from 1958 to 1962.

And his Canadian Bill of Rights – something Diefenbaker had been working on at the provincial level since the mid-1930s. Plamondon views Diefenbaker’s ultimate implementation of this legislation as a necessary precursor to Pierre Trudeau’s 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms. He describes how, although the bill had no constitutional authority, with time it was referenced in numerous court cases and increasingly influenced judicial decisions. Notably, in R. v. Drybones, the Supreme Court of Canada nullified a section of the Indian Act due to its differing treatment of an off-reserve-living native compared to a white man.

All these achievements would likely pass muster with our latter-day moral arbiters, who have so far refrained from cancelling Diefenbaker as they’ve done with Sir John A. MacDonald, Egerton Ryerson and others. This part of the Chief’s legacy speaks more to his upholding enduring values than to what might be fashionable today.

What shaped John Diefenbaker’s commitment to minority and Indigenous rights?

“Consciousness of Injustice”

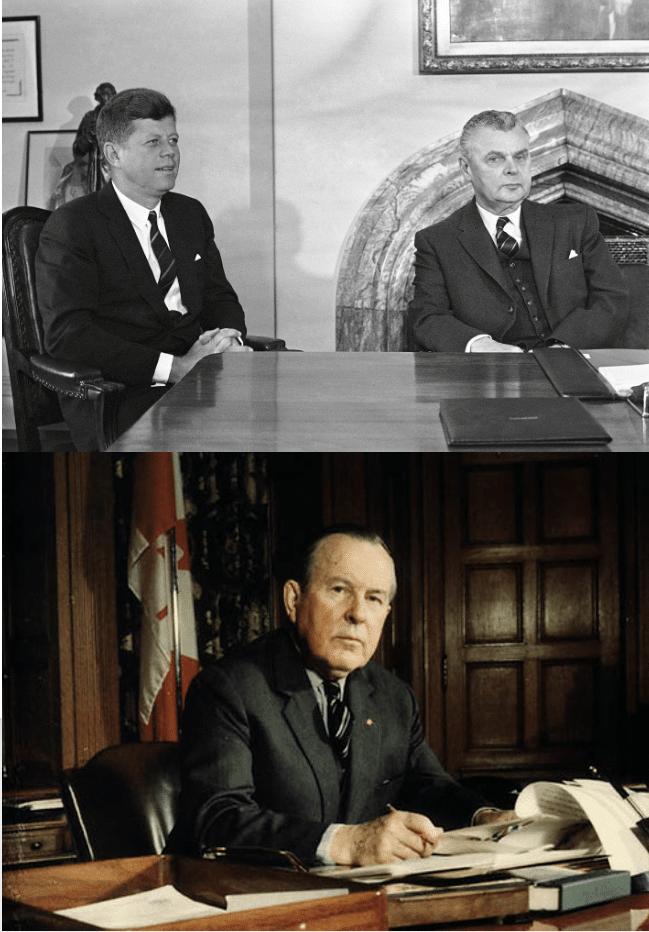

It’s striking how many of the issues and challenges faced by Diefenbaker persist today, with a bit of a modern veneer. These jump out in Plamondon’s narrative. As Prime Minister, Diefenbaker had a notoriously frosty relationship with U.S. President John F. Kennedy. The generational and class differences between them were exacerbated by differing personalities. Said the president to his brother Robert after a Diefenbaker visit to Washington: “I don’t want to see that boring son of a bitch again.”

But Kennedy’s ire went further. He actively cultivated a relationship with Canada’s Liberal Opposition Leader, Lester Pearson, and even interfered in the 1963 federal election, which produced a Liberal minority. The U.S. State Department had been continuously monitoring discord in the PC cabinet over deployment of U.S.-made nuclear-armed anti-aircraft missiles in Canada (an American priority at this point in the Cold War) and, early in 1963, issued a press release “clarifying” statements made by various Canadian officials, including the Prime Minister. This served to destabilize Diefenbaker’s government, precipitating an election.

As Plamondon recounts in his chapter on Canada-U.S. relations, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy bragged to Kennedy that he and Secretary of State George Ball had “knocked over the Diefenbaker [government] by one innocuous press release.” In the campaign that followed, Kennedy also lent the Liberals his best pollster, Lou Harris, who later told the Canadian Press he’d made a “lifelong friend” of Pearson and that helping him defeat Diefenbaker was “one of the highlights of my life.” Plamondon notes that a Washington Daily News columnist channelled Kennedy in revelling over the defeat of the “crypto-anti-Yankee” Diefenbaker government. Donald Trump, apparently, isn’t the first U.S. President to prefer softer, malleable, ingratiating Canadian prime ministers.

A belief in the essential equality of all Canadians was central to Diefenbaker’s political philosophy, and resonates against the current ideology of identity politics. The Chief was an inveterate opponent of what he called “hyphenated Canadian[ism]”, which at the national level he contrasted with his idea of “One Canada”. Dief was bewildered, as one might be, by how emphasizing differences could bring unity. As Plamondon notes, at one point Dief remarked to his Cabinet that it was hard to see how “unity and the development of one nation would be furthered by the…perpetuation of a system which emphasized the racial origins of the groups that made up the population.”

This core belief led to accusations that he didn’t “get” Quebec or understand the concerns of French Canadians. His rivals in the PC party were advancing a policy of deux nations, which sought to placate Quebec’s demands. Sixty years on, it’s likely that Diefenbaker was more right than wrong, given the perpetuation of Quebec’s grievances and how many Canadians don’t fit into either of the “nations”.

Freedom Fighter is a welcome, necessary addition to Canadian historiography. Plamondon has done a commendable job portraying Diefenbaker as a flawed but great Canadian leader, relevant in our troubled era.

Plamondon argues that Diefenbaker’s commitment to individual liberties and freedom was “baked in” from his youth. Quoting the Chief’s memoirs: “At an early age, I developed a consciousness of injustice, which has never left me. The idea of the poor being treated differently, the working man looked down upon as a digit, filled me with revulsion. I was beginning to add to my highland inheritance an acquired distrust of powerful forces and concern over their overwhelming impact on the helpless.”

Lastly, Diefenbaker’s embodiment of Western populism and discontent couldn’t be more relevant today. From early in his career, he defended “the little guy” – farmers, First Nations, western Canada in general. He railed against the “lords of opulence” in Winnipeg whose stranglehold on grain marketing depressed farmers’ incomes; it would be left to a Conservative prime minister 50 years later to do away with the Canadian Wheat Board.

His locking horns with central Canadian media, whom he dubbed the “Eastern Magnates”, also rings very familiar; nowadays they are better-known as elements of the Laurentian Elite. They thought Diefenbaker was unfit to lead – as they do of virtually every Conservative leader today. Conflict with the likes of PC party president and back-room schemer Dalton Camp, or even Bank of Canada head James Coyne, cement Diefenbaker’s image as an outsider fighting against the machine. It’s easy for Plamondon’s readers to see western Canada’s current frustrations mirrored in Diefenbaker’s struggle with the forces arrayed against him.

Freedom Fighter is a welcome, necessary addition to Canadian historiography. Plamondon has done a commendable job portraying John Diefenbaker “warts and all”, not “just warts” as other biographers have done. He portrays the Chief as a flawed but great Canadian leader, relevant in our troubled era. He also shows that Diefenbaker’s vision represents a road not travelled that might now have Canada in a better place had he prevailed over his political opponents.

How did John Diefenbaker embody Western populism in Canadian politics?

John Diefenbaker’s political persona was often identified with Western Canadian Prairie populism. From challenging central Canadian elites to defending farmers and members of First Nations, the man who became universally known as “The Chief” consistently sided with those he saw as overlooked by the system. He railed against the “lords of opulence” in Winnipeg, fought the grain marketing system, and battled figures like Progressive Conservative party president Dalton Camp and Bank of Canada Governor James Coyne. Diefenbaker’s clashes with Eastern news media and party insiders cemented his image as a political outsider using populism to champion the West.

John Weissenberger is a Calgary geologist, freelance writer and amateur historian.

Source of main image: Diefenbaker, John George, 1895-1979, retrieved from University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections.