Michael Ignatieff, former leader of the federal Liberals, was famously annihilated in the 2011 election: losing his own seat, dropping the Liberals to third party status and handing Prime Minister Stephen Harper his coveted majority government. And key to that inglorious defeat was the manner in which the Harper Conservatives defined their untested opponent. After spending almost his entire working life outside the country as a public intellectual, television commentator and writer, Ignatieff – grandson of a Russian count and son of famed Canadian diplomat George Ignatieff – had returned to the country of his birth to claim his inheritance as Canada’s next Liberal Prime Minister. A Conservative brain trust that built Harper’s image on the prosaic patriotism of Tim Horton’s coffee, hockey, history and military pride knew exactly what to do with that story line. “Just visiting” snarled one Conservative attack ad during the 2011 campaign. “He didn’t come back for you” snapped another.

Not only were the ads effective in characterizing Ignatieff as a privileged, out-of-touch egghead, but they were quickly proven true. The day after his ignominious defeat, Ignatieff stepped down as Liberal leader. A year-and-a-half later he decamped to Harvard. And in 2016 he moved even farther afield − to Hungary − to become president and rector of Central European University (CEU), an English-language graduate school in Budapest.

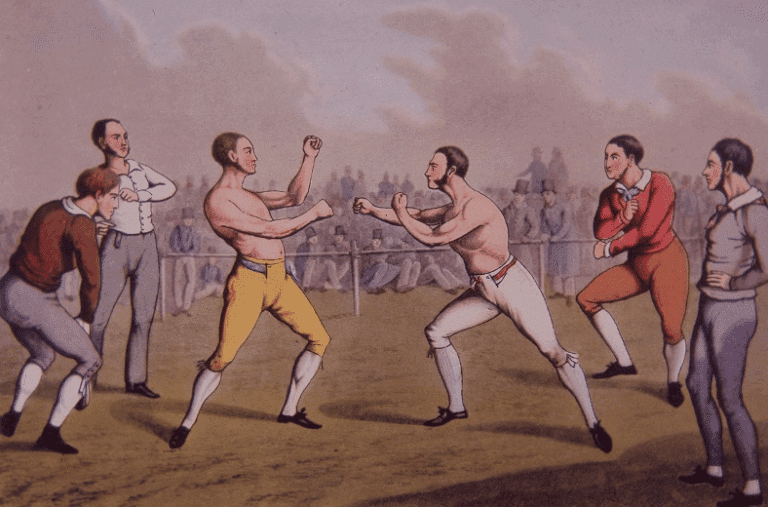

But since then a funny thing has happened to Canada’s most famous political visitor. Perhaps as a result of the mugging he took from Harper’s hitmen, the 70-year-old Ignatieff seems to have discovered the art of a successful counterpunch. In Budapest, he’s in the midst of another high-stakes scrap with an even more belligerent political foe, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. But this time around Iggy’s giving as good as he gets. In fact, he might even come out on top in his scrap with Eastern Europe’s premier political bully. For friends of liberal democracy, there’s a lot to like about the new, battle-toughened Michael Ignatieff.

But first, how did he end up in Hungary? “The CEU job was interesting to me because my wife Zsuzsanna is Hungarian so we have family here, because it is a very good school, and because I thought it would be interesting,” an affable Ignatieff explains in a lengthy interview at CEU’s campus in downtown Budapest late last year. “But I didn’t realize,” he adds after a beat, “that it would be this interesting.”

As president of CEU, Ignatieff has been thrust into a heated battle between Hungary’s formidable Prime Minister Orban and billionaire philanthropist George Soros. Orban is widely seen in the West as part of a dangerous worldwide shift towards nationalist strongmen. He takes a hardline stance on immigration, displays a worrisome partiality for court-stacking, and his close friends seem to become very wealthy. He once even boasted of creating an “illiberal democracy” in Hungary. The Hungarian-born Soros, on the other hand, made his money in currency speculation and has since dedicated his wealth and influence to the promotion of democracy, free speech and a variety of progressive causes throughout the world, including as major backer to Hillary Clinton’s disastrous presidential campaign. Conflict between these two titans arises from Soros’ strident advocacy of open-borders during the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis and Orban’s nationalist predilection for closed borders. Hungary, in fact, recently completed a Trump-like fence along its boundary with Serbia to put a stop to illegal immigration. As effective nationalism typically requires an external villain to rally domestic voters, Orban has found his requisite foil in the New York City-based Soros.

The scale of conflict between Soros and Orban has no real parallel in Canadian politics. Last fall, for example, Hungarians were asked to participate in a ‘public consultation’ on the so-called Soros Plan for immigration, even though such a thing doesn’t formally exist and Soros has no role in Hungarian politics. Many of the government’s questions on this faux referendum were either deliberately provocative or outright deceptive. (Agree or Disagree: migrants should receive milder sentences for crimes they commit.) During the consultation period, Orban also ran a massive government publicity campaign – the drive from Budapest’s international airport to downtown was plastered with billboards featuring the same grinning picture of Soros every few hundred metres.

Ignatieff and his school are collateral damage in Orban’s war on Soros. CEU was set up in Budapest in 1993 with funding from Soros to advance liberal democratic values in Eastern Europe. As part of his efforts to advance illiberal values, Orban last year unveiled new education regulations threatening all foreign-accredited universities operating in Hungary, including CEU (which grants degrees registered in New York State), with closure. “This piece of law is a targeted political attack,” says Ignatieff. “We are being held hostage to a regime that paints us as ‘that Soros University,’” a claim he says is false since Soros no longer has any direct role in CEU. Orban’s move has likely been inspired by Russian President Vladimir Putin, who recently used a similar tactic to strip another freedom-minded, Soros-funded university in St. Petersburg of its ability to teach.

Ignatieff responded with a rapid, multi-pronged counterattack. He convinced 14 Nobel Prize winners to sign a letter of support amid a deluge of international criticism aimed at Orban. The Hungarian Academy of Sciences passed a resolution calling for CEU to remain open. The U.S. State Department – President and Orban fanboy Donald Trump’s State Department, no less – also issued a statement backing the school and touting its “strong bipartisan support.” A street march in April drew an estimated 10,000 students, staff and university supporters. A week later another march saw 50,000 to 80,000 Budapest residents take to the streets in defense of academic freedom. Public demonstrations of this sort are politically significant in Hungary, which has a long tradition of street democracy, including the famous 1956 Uprising against the Soviets. And while Orban may be a bully, he’s also an effective politician with a keen sense of the public mood. When similarly-sized marches opposed a planned Internet tax and Budapest’s putative Summer Olympics bid, he swiftly changed course both times rather than put himself offside popular sentiment. “Orban is responsible to public opinion,” notes Ignatieff, who seems confident the streets are on his side. “One of the reasons they are coming after us is that we are one of the last free institutions left in Hungary.” Bold talk from someone many Canadians remember as the ultimate political pushover.

When he competed for power in Canada, Ignatieff struggled to resolve the conflict between his intellectual curiosity and the grimy necessities of political life. “Academics are supposed to be tremendously smart, but one of the things about academics is that they often comically and cruelly lack good political judgement,” he remarked quite presciently, and without irony, during his keynote speech at the 2005 federal Liberal convention, which launched his ill-fated Canadian political career.

There’s no shortage of examples where Ignatieff’s intelligence got the better of his political judgement. He famously supported U.S. President George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq because he’d heard first hand accounts from Iraqi Kurds about Saddam Hussein’s gas attacks. (He only disavowed the invasion after he became a Liberal MP and Hussein’s “weapons of mass destruction” turned out to be a mirage.) He was a reliable supporter of Canada’s Afghanistan mission when many other Liberals weren’t. He backed Harper on a harmonized sales tax. He took a realistic and nuanced position on torture and terrorism. And during the 2011 election, he mostly avoided the sort of negative campaign ads that proved so effective against him. All these principled positions cost him real partisan advantage. Then, in the final days of the campaign, he revived politically toxic talk of an informal coalition with the NDP and Bloc in an interview with CBC’s Peter Mansbridge, largely because he couldn’t resist discussing how such a thing might operate under the rules of Parliament. Ignatieff was perhaps too smart and too principled to succeed in Canadian politics.

But that was then. Now he’s in an arena where intellectualism is an advantage rather than a liability. His mobilization of elite support from inside and outside Hungary hints at the scope of a massive contact list built up from decades as a globe-trotting boffin. And he seems to have learned a thing or two about positioning, narrative and political nous. “I haven’t met with any opposition politicians publicly or privately since I took this job,” he reports. “My job is exclusively the defense of this institution.” No coalition talk this time around.

Freed from the demands of political leadership, Ignatieff is also an interesting writer once more. His latest book “The Ordinary Virtues: Moral Order in a Divided World,” released last year, is the product of a special assignment from the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs in honour of its centennial. The organization commissioned Ignatieff to tour the world in search of evidence of the fulfilment of philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s industrial age evangelical dream of a universal morality. The idea being that 21st century innovations such as the Internet, world trade and UN-ordained global governance were finally bringing humanity together under a common set of moral values in a way that religion never could.

Ignatieff wound up rubbishing the dream. After travelling from the ganglands of Los Angeles to the slums of South Africa and Brazil to the jungles of Myanmar and the old battlefields of Bosnia looking for a unifying new world morality, he came to the conclusion such a thing is sheer poppycock. “A global ethic, applicable to all mankind, is essentially unimaginable and irrelevant,” he writes. “Globalization of our economies does not produce globalization of our hearts and minds.” In stark contrast to his dreamy successor as Liberal leader, who famously imagines Canada as the world’s first “post-national” state and issues reckless open invitations to the world’s sea of refugees, Ignatieff recognizes that despite the wishful thinking of global utopians, everyone and every country remain relentlessly focused on their own backyard. When we do act for the benefit of others far from our immediate neighbourhood, it’s out of pity rather than conformity to international human rights dogma; we remain a tribal, rather than global, people. While he still calls himself a human rights scholar, Ignatieff seems refreshingly grounded in gritty reality.

He even allows that Orban has a point when it comes to the immigration issue at the crux of the spat with Soros. “I would not agree with the forced imposition of refugee quotas on any country,” he says. “No country can exist without firm and effective border control.”

Following Ignatieff’s successful turn as street protest impresario and his careful orchestration of international and domestic support, even pro-Orban intellectuals in Hungary admit, in private conversation, that the government probably made a mistake in trying to take down one of the country’s most prestigious schools. Perhaps in evidence of this, Orban recently changed tactics. While other foreign universities, such as the Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, were permitted to sign deals protecting their future, CEU was instead slapped with a 12-month moratorium on such negotiations. This has the effect of placing the school in limbo for a year – at least until the Hungarian national elections are over and Orban can back down without losing face. And while this move may affect the school’s ability to recruit students and staff over the short term, it also hints at CEU’s long-term survival. The school’s punishment for being linked to Soros may simply be one year of living uncertainly.

It’s too soon to call it a win, but CEU’s future seems more secure now than it did last spring when Lithuania was offering the school a new home. “I want to keep CEU in Budapest,” says Ignatieff, claiming his role in the school’s defense is more than just a day job. “I have Hungarian family and a personal stake here. I’m not just passing through. Next to Canada, this is the country where I have the deepest roots.”

Of course one cannot hear that comment without being reminded of his feeble pushback against the “just visiting” rap in Canada. So did he learn anything from that visit? “I’m certainly glad of my time in politics, and it has served me well now,” he admits. In his struggles with Orban − and especially the way he has defined CEU’s narrative as a bulwark of academic freedom and democracy in an increasingly illiberal Hungary − he seems a much savvier and better prepared adversary than voters in Canada will remember. But do those old barbs still hurt?

“It stung at the time,” he says, after a long and reflective pause. “I was angry that Stephen Harper got away with framing me as ‘not one of us.’ He got away with it because he was a very effective politician – and that’s politics.” Having learned a thing or two about politics in the experience, however, this former Liberal leader is now a far more formidable opponent. And Hungarian democracy, if not Canadian, is the better for it.