The health of my patient will be my first consideration; I will not use my medical knowledge to violate human rights and civil liberties, even under threat.

—World Medical Association: Declaration of Geneva, 2006

Where all men think alike, no one thinks very much.

—Walter Lippmann, 1937

We all remember when it was natural to strike up a conversation with a stranger on a street, in a mall or in a café. Sharing a smile would often start the enjoyable process from which mutual trust and understanding could flow. Seeing other people’s open faces and hearing them laugh felt contagious and energizing. A spontaneous encounter had a chance to turn into something long-lasting and meaningful.

Those times were pre-Covid-19; the pandemic has brought great upheaval to social norms. Rarely do many of us talk to strangers in public places. Communication is largely transactional – aiming a few words at a clerk behind a plexiglass shield and straining to hear the muffled reply. Laughter has become a rarity. And even if others smile at us, we hardly can tell – or know when to smile back. All we see are faces largely hidden behind masks and staring, shifting or downcast eyes.

Happily, that is beginning to change. Mask mandates are dropping left and right across the United States. As of June 8, 35 U.S. states had removed these requirements in indoor or outdoor public settings. A few U.S. governors have even prohibited local governments and school boards from countermanding such state policy. At the same time, the exposure of Anthony Fauci’s serial contradictions has loosened his grip on the American psyche – weakening the entire pro-mask side. Gathering limits are disappearing as well; the recent Indy 500 was packed with mostly unmasked auto race enthusiasts and fans are once again jamming stadiums for pro sports.

If Canada is to enter a major political struggle over the possibility of long-term masking, then surely it is worth revisiting the basic question of whether masks actually work.

In Canada, a number of provinces are also reopening – led in speed by Alberta, where all provincial restrictions will be dropped within two weeks of 70 percent of the population receiving one dose of vaccine. That pointedly includes the mask mandate. If this occurs, and much of the rest of Canada follows suit, the summer of 2021 could end up being, if not exactly the “best summer ever” in the previous hopeful words of Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, then at least one to rekindle normal life and, perhaps, look back upon as the time when the Covid-19 pandemic was put in its grave.

These lovely sentiments – surely shared by millions of Canadians – could be dashed, however. Reopening is threatened by a number of political leaders, urged on by an entrenched medical/scientific faction, who appear almost terrified of normality’s return and whose default position is to lock down, prohibit and prevent. Ontario, for example, only re-authorized camping last Friday and recently extended its state of emergency until December. Premier Doug Ford, wrote Matthew Lau in the Financial Post, “has turned the presumption of liberty completely on its head. In Ontario there is now a presumption of government control.”

Even in Alberta, big-city mayors are suggesting they might defy the province’s mask mandate lifting. They are egged on by vocal medical experts who have formally demanded that masks remain in place until 70 percent of the population has had two vaccine doses. This may amount to something like “forever,” since vaccination curves in other countries to date have gone nearly flat at approximately 55-65 percent with even one dose. Alberta, it was reported last week, is having trouble achieving the last several percentage points leading to 70 percent with one dose.

In short, if some have their way, it could be masks for a long time. Should further new Covid-19 variants or new infectious diseases come along in the meantime, it might be masks forever.

If Canada is to enter a major political struggle over the possibility of long-term masking, then surely it is worth revisiting the basic question of whether masks actually work. And, even if masks are shown to be useful in slowing the transmission of Covid-19, the public has a right to understand whether habitual mask-wearing carries negative health effects, in order to weigh the costs against the benefits of such an intrusive long-term policy.

With those questions in mind, C2C Journal brings you this exclusive, carefully researched two-part analysis. In Part I, we review the recent history of mask requirements and discuss the initial evidence around widespread mask-wearing.

When it Began: The WHO Mask Guidance

On April 6, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued Interim Guidance on the use of facemasks against Covid-19. The organization advised only health professionals to wear medical masks or respirators and to avoid non-medical masks because the effectiveness of the latter, it stated, was not established.

Significantly for the wider population – or seemingly so – it also cautioned that “the wide use of masks by healthy people in the community setting is not supported by current evidence and carries uncertainties and critical risks.” Among these were potential self-contamination by frequent touching and re-wearing of single-use masks, breathing difficulties and a “false sense of security, leading to potentially less adherence to other preventive measures such as physical distancing and hand hygiene.”

The WHO’s April guidance was consistent with the statements of numerous public health officials worldwide. It was, for example, preceded by the official statement by Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam who suggested that “putting a mask on an asymptomatic person is not beneficial, obviously if you’re not infected.”

The official advice should have been unsurprising, even though by this time millions of individuals were rushing to scour store shelves for any and all mask varieties, while others rigged up bizarre contraptions out of old diving helmets or even fish bowls, and a few were seen shuffling down aisles in full hazmat suits (real or home-fashioned). But the official advice was consistent with decades of established international guidance for the management of disease outbreaks, in which masks are recommended for those who are sick – to protect the healthy – but not ubiquitously (see, for example, the WHO’s guide of 2018, or Public Health England Principles of 2015, or the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada Primer on Population Health).

Physician Margaret Harris, a member of the WHO’s coronavirus response team, was quoted saying that “the mask is almost like a talisman,” making “people feel more secure and protected.” An official scientist appeared to say that mask-wearing was no longer about science, but about sorcery and emotion.

Regardless of how sound these recommendations are, they soon were thrown overboard as fears spread of “asymptomatic spreaders,” many doctors and scientists started asserting benefits to the public wearing almost any sort of mask, and governments and international organizations sought to reassure jittery populations they were taking “crucial steps” to “save lives” – which now included requiring people to wear masks in a variety of settings.

The WHO subsequently updated its mask guidance, with the most recent document issued on December 1, 2020. Citing a number of studies, this one advised the general public to wear either medical or three-layer fabric facemasks in indoor and outdoor settings where ventilation is inadequate and physical distancing is less than 1 metre. It asserted several pandemic control benefits to such practice, including reduced spread of viral respiratory droplets and reduced stigmatization towards mask-wearers (a transient phenomenon early in the pandemic). Further stated benefits included making people feel that “they can play a role in contributing to stopping spread of the virus,” encouraging proper hygiene and, finally, reducing transmission of other respiratory illnesses such as tuberculosis and influenza.

The WHO’s list of disadvantages, however, had grown significantly and now also included potential headaches, facial skin problems, difficulties communicating, discomfort, improper mask disposal, poor compliance among young children and difficulties for people with developmental challenges, with chronic respiratory problems or those living in hot and humid conditions. Nor should this have been surprising either, for as we shall see it too was consistent with longstanding scientific understanding. None of these mask-associated risks, however, received a thorough airing in news and social media.

On the contrary, many governments imposed even more stringent and often duplicative requirements, like requiring masks and distancing even outdoors where ventilation was good, or masks and plexiglass barriers, or masks, face shields and distancing. Masks, meanwhile, took on novel roles as political statements or articles of faith employed by political leaders, organizations, public health figures and much of the population. People were even seen swimming with paper masks. Physician Margaret Harris, a member of the WHO’s coronavirus response team, was quoted in an NPR column saying that “the mask is almost like a talisman,” making “people feel more secure and protected.” An official scientist appeared to say that mask-wearing was no longer about science, but about sorcery and emotion.

Meanwhile, no one in the public sphere seemed willing to peruse the WHO’s December 2020 guideline in detail. Had they done so, they might have noticed two statements eerie in their juxtaposition. First, the WHO clearly recognized the serious limitations of the studies it cited about the efficacy of masking to reduce viral spread: “[The] studies differed in setting, data sources and statistical methods and have important limitations to consider notably the lack of information about actual exposure risk among individuals, adherence to mask wearing and the enforcement of other preventive measures.” Second, the WHO nonetheless insisted on universal mask usage: “Despite the limited evidence of protective efficacy of mask wearing in community settings, in addition to all other recommended preventive measures, the [guidelines development group] advised mask wearing.”

The WHO’s categorical recommendation, then, rested on admittedly shaky foundations. Over half a year has passed. One would expect there to be an ever-growing number of studies dedicated to Covid-19 and related issues, including masking. And so there has been.

Current Evidence on Mask Effectiveness

More than 300 scientific papers have been published specifically on masking during the pandemic. The best way to evaluate such a vast body of research without losing the forest for the trees is to focus primarily on literature reviews and systematic reviews (special types of scientific analysis that summarize up-to-date knowledge on a particular issue). This narrows the search to some 20 review studies (as of May 2021). Six of these provide support for universal mask wearing using epidemiological data (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). Six others offer mechanical evidence by describing material and filtration properties of masks. Two reviews are inconclusive (this and this), while the rest are less relevant (comparing medical masks to N95 masks in a healthcare setting, for example, this).

The University of Hawaii team’s conclusion appears decisive: “All available epidemiologic evidence suggests that community-wide mask-wearing results in reduced rates of COVID-19 infections.”

The most recent and comprehensive review is by researchers from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, published in April 2021. This interdisciplinary report outlines the “state-of-the-art understanding of mask usage against Covid-19” by covering the most important epidemiological data, face mask filtration mechanisms and mask recontamination and reuse.

In their epidemiological evidence the researchers cite eight publications that report a positive association between mask wearing and a reduced risk of Covid-19 infection. These studies were conducted in China, Thailand, the U.S., Germany and Canada. The Canadian evidence notably encompassed both provincial data from Ontario and nationwide data analyzing the effect of mask wearing on Covid-19 case numbers over the course of eight months. “In the first few weeks after their introduction, mask mandates are associated with an average reduction of 25 to 31% in the weekly number of newly diagnosed COVID-19 cases in Ontario,” the study concluded. It also speculated that had indoor masking been mandated by early July, there would have been 25-45 percent fewer weekly cases across the country than actually occurred.

The other studies were different in methodology and reported varying strengths of the association between mask wearing and risk reduction, ranging from 15 percent to 80 percent. The University of Hawaii team’s conclusion appears decisive: “All available epidemiologic evidence suggests that community-wide mask-wearing results in reduced rates of COVID-19 infections.”

Not All Science Is Created Equal: RCTs vs. Observational Studies

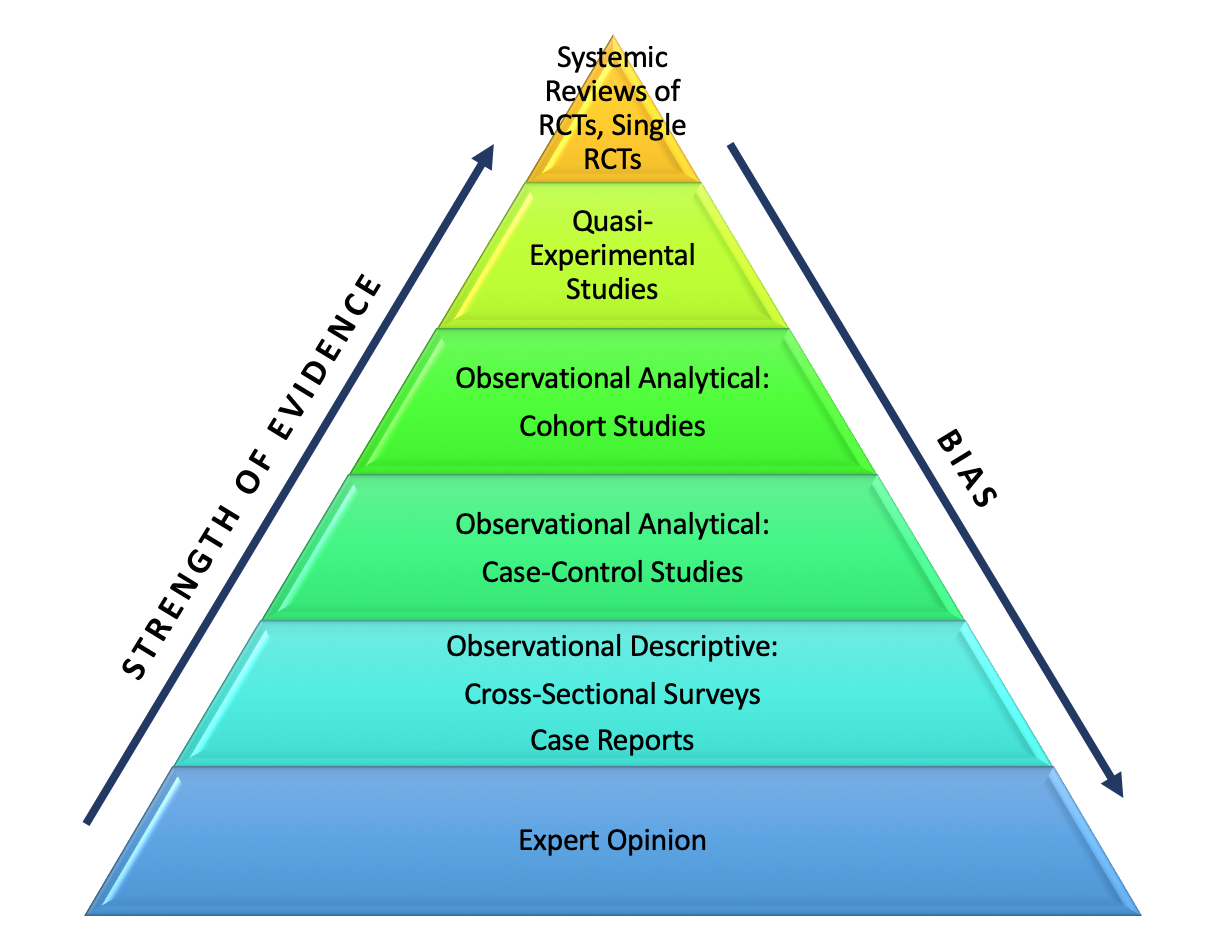

The take-home message from the above research appears unequivocal: masks work. The factual conclusion provides scientific support for the political decision to impose a public mask mandate. But for one fact: nearly all Covid-19-related epidemiological studies are either observational analyses (such as this or this), simulation studies (such as this), or a combination thereof (like the Canadian study described above). Almost none involved randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Why does that matter?

The distinction between study types is imperative for it speaks of the quality and not simply the quantity of the available scientific evidence. Setting aside simulation studies that are hypothetical and therefore of lesser empirical value, it is important to understand the differences between RCTs and observational studies (case-control and cohort studies are two types).

With respect to influenza, five out of six randomized controlled trials conducted in healthcare settings found no significant difference between mask-wearing and control groups…None of four RCTs performed in broader community settings found a significant difference between masking and remaining bare-faced.

The RCT facilitates an objective comparison between various types of intervention, or between treatment and non-treatment. The RCT achieves this by using the process of randomization, assigning participants randomly either to experimental or control groups. The goal of such studies is to prevent manipulation of the results and to draw, as accurately as possible, a causal relationship between an intervention, or a behaviour, and the subsequent outcome.

The link of causality cannot be achieved in observational research, which involves analyzing data gathered in natural conditions without researchers’ intervention. Although observational studies are illuminating and useful in various scenarios, they are inevitably biased. The bias occurs because such studies do not allow for direct control over confounding variables that may have an impact on the study results. For example, for one to say that “A causes B” requires ensuring that the effects of all other important variables on B have been removed or cancelled through randomization.

This is impossible in observational studies, always leaving a chance that the observed outcome B might have been caused by a variable, or variables, other than A. Thus, observational studies, even those employing advanced statistical analyses, cannot reach conclusions stronger than establishing temporal associations between one thing and another. But association, or correlation, does not demonstrate causation. (The Canadian study cited above, for example, notes that mask mandates are “associated” with a reduction in the rate of Covid-19 infection; it does not assert a causal relationship.)

The Odd Reluctance to Conduct RCTs in Regard to Public Health Matters

Which brings us back to the 300-odd mask-related studies conducted in the Covid-19 era. Many, indeed, found associations or correlations between widespread adoption of masks and a reduction in Covid-19 case counts, or a slowing of acceleration in case counts. In an observational study like this one, however, it is reasonable to ask whether the detected reduction in Covid-19 transmission was caused by mask wearing. Could it not have been due to other preventative health measures adopted around the same time, such as improved hand hygiene, limited social interaction, physical distancing in public settings or even individuals’ general health regimen? And what about the impact of other variables such as age or race on the risk of catching the virus? Finally, could there be other, as-yet overlooked confounders that affect virus spread? Randomization is required to negate the effects of the confounding variables, known or unknown.

Because of these known limitations of observational studies, the RCT is recognized as the gold standard of clinical research practice, a rigorous tool of cause-and-effect analysis. One of the world’s leading experts in medical standards and statistics, Dr. Janus Christian Jakobsen, who is frequently cited for her systematic reviews of meta analyses, authoritatively stated:

“Clinical experience or observational studies should never be used as the sole basis for assessment of intervention effects – randomized clinical trials are always needed…Observational studies should primarily be used for quality control after treatments are included in clinical practice.” (Emphasis added.)

It is thus clear that in health-related contexts, researchers should rely on RCTs whenever possible and use observational studies to gather supplementary evidence.

The most common arguments against RCTs are that they are expensive, time-consuming and impractical for population-wide interventions. There are also understandable ethical objections against exposing healthy control groups to contagious and potentially fatal infections, in this instance attempting to determine whether unmasked people are more likely to catch Covid-19. In fact, some have asserted, in reference to the WHO, that “we should not generally expect to be able to find controlled trials” in the context of population health measures.

Still, it has been over a year since mask mandates were first imposed in many countries. Given the prodigious effort poured into seemingly anything to do with Covid-19, this should be ample time for researchers to gather resources and test mask effectiveness in a controlled experimental setting. Nor was it unheard-of prior to the pandemic to perform RCTs in healthcare and wider-population settings to evaluate the effect of mask wearing on the transmission of respiratory illnesses such as influenza (see this review of 2010) and influenza-like illness (also see this scoping review of 2020). These studies clearly overcame objections related to practicality and ethics. Why should Covid-19 be different?

The cited reviews present intriguing details: with respect to influenza, five out of six RCTs conducted in healthcare settings found no significant difference between mask-wearing and control groups. Even more important from the standpoint of the current pandemic, none of four RCTs performed in broader community settings found a significant difference between masking and remaining bare-faced. For influenza-like illnesses, the pooled data from five other RCTs as well showed a non-significant protective effect of mask wearing for avoiding either primary or secondary infection. These results appear substantial and would seem of some relevance to the current pandemic. But there is more.

End of Part I.

Coming next in Part II: Should you care whether masks are more like a sieve or a filter? Is there really no RCT-generated “gold standard” evidence regarding whether wearing masks reduces the spread of Covid-19? And is there any basis to concerns of ill effects from wearing masks?

Maria (Masha) V. Krylova is a Social Psychologist and writer based in Calgary, Alberta who has a particular interest in the role of psychological factors affecting the socio-political climate in Russia and Western countries.