Dead Wrong: How Canada Got the Residential School Story So Wrong is a follow-up to Grave Error, published by True North in late 2023. Grave Error instantly became a best-seller and continues to move briskly on Amazon. Both books were edited by C.P. Champion and myself, Tom Flanagan. People wanted to read the book! Why? Because they heard through word-of-mouth as well as from alternative media that it contained well-documented information not readily available elsewhere concerning the history of Canada’s Indian Residential School (IRS) system and the facts surrounding recent claims about “unmarked graves”.

Why is another book needed? Simply put, because the struggle for accurate information continues. Very few of those who promulgated unsubstantiated claims or rumours about “discoveries” of the “remains of missing children” at Kamloops and other former IRS sites have admitted their errors. Outrageously, the New York Times, to some still the world’s most prestigious newspaper, has never retracted its absurd and inflammatory headline that “mass graves” (suggesting the commission of a deliberate atrocity) were uncovered at Kamloops.

Dead Wrong: How Canada Got the Residential School Story So Wrong is a sequel to the best-seller Grave Error; it dismantles the many falsehoods and distortions surrounding Canada’s former Indian Residential School (IRS) system, most notably that the “remains of 215 children” were discovered at the Kamloops IRS (right). (Source of right photo: Aaron Hemens)

Dead Wrong: How Canada Got the Residential School Story So Wrong is a sequel to the best-seller Grave Error; it dismantles the many falsehoods and distortions surrounding Canada’s former Indian Residential School (IRS) system, most notably that the “remains of 215 children” were discovered at the Kamloops IRS (right). (Source of right photo: Aaron Hemens)Despite this grudging admission, however, the First Nation’s government still has not carried out excavations that would determine whether or not there are human remains under the former apple orchard close by the old school building. Up to this point, the one reliable excavation carried out at a former IRS site, the Pine Creek Residential School in Manitoba, found nothing. Other excavations have led to claims of finding bones, but these were done near mission churches and community cemeteries, where it was long known that legitimate and documented burials had taken place. It is not surprising to find bones if you dig in a cemetery!

Some reporters and politicians have become more careful about their wording, using phrases like “potential gravesites” or “possible burials”. Canadian legacy media outlets, however, have largely doubled down on the Kamloops narrative. CBC, CTV, Global TV, the Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail and many other media outlets carry on as if nothing has changed since the May 27, 2021 announcement. Globe reporter and columnist Tanya Talaga’s 2024 book The Knowing was glowingly reviewed and nominated for the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Journalism, despite erroneously accepting the non-discovery at Kamloops.

What evidence supports the Kamloops “unmarked residential school graves” claim?

The announcement in May 2021 by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation claiming to have found buried remains of schoolchildren originated from a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey that identified “anomalies” in the soil. Such disturbances can be anything from old construction materials or decayed building foundations to animal or human bones. GPR surveys cannot specify the nature of such soil disturbances, however, i.e., identify “human remains”. As books like Dead Wrong (published November 2025) highlight in their pursuit of the truth, the Kamloops First Nation has not yet carried out excavations to determine whether any human remains are present. To date, the one reliable excavation at a former Indian Residential School site, Pine Creek in Manitoba, found nothing.

The legacy media also have offered hagiographic coverage of the so-called documentary Sugarcane, a feature-length film sponsored by National Geographic which was even nominated for an Academy Award. Dead Wrong’s editorial team is not aware of any reporters or columnists who spotted the dozens of factual errors in Sugarcane. The sole exception is independent journalist Michelle Stirling, working closely with researcher Nina Green, whose analysis entitled “The Bitter Roots of Sugarcane” is included in Dead Wrong. It charts these errors that, taken together, enabled Sugarcane to tell a fundamentally false tale whose villains are, of course, former IRS officials and clergy. It is important to get this straight because Sugarcane is bound to be inflicted upon generations of defenceless Canadian schoolchildren.

Because Kamloops is in British Columbia, it is not surprising that many of the “unmarked graves” narrative’s aftershocks occurred in that province. The Sugarcane pseudo-documentary was one; the movie’s story is centred on St. Joseph’s IRS, located near Williams Lake, less than 300 km northwest of Kamloops. Several other incidents are also described in Part I of Dead Wrong, entitled “How B.C. Went Berserk.”

Independent journalist Michelle Stirling (left), a contributor to Dead Wrong, charted the factual errors in the 2024 pseudo-documentary Sugarcane – a fundamentally false tale whose villains are former IRS officials and clergy. At right, a “crime wall” scene from Sugarcane. (Sources: (left screenshot) YouTube/Michelle Stirling; (right photo) © National Geographic Documentary Films/Courtesy Everett Collection)

Independent journalist Michelle Stirling (left), a contributor to Dead Wrong, charted the factual errors in the 2024 pseudo-documentary Sugarcane – a fundamentally false tale whose villains are former IRS officials and clergy. At right, a “crime wall” scene from Sugarcane. (Sources: (left screenshot) YouTube/Michelle Stirling; (right photo) © National Geographic Documentary Films/Courtesy Everett Collection)In the spring of 2024, for example, the small city of Quesnel (400 km northwest of Kamloops) made national news when the mayor’s wife bought ten copies of Grave Error for distribution to friends. After numerous noisy protests held by people who had never read the book, Quesnel city council voted to censure Mayor Ron Paull and tried to force him from office. Paull won a victory in the courts and his wife, Pat Morton, is now suing the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs for defamation. But the couple have had to endure many headaches and expenses. It’s all described in Chapter 1, written by me.

Then there was the attempt to rename the Sunshine Coast community of Powell River because it was supposedly named after Israel Powell, a 19th century B.C. Superintendent of Education who was supposedly a founder of an IRS in B.C. (he wasn’t) and who supposedly sent Indian children from Powell River to Kamloops (he didn’t). It’s not even completely clear that the town was named after him; it may have been named after another Powell. Frances Widdowson tells that story in our book.

B.C. MLA Dallas Brodie was expelled from Opposition Leader John Rustad’s shadow cabinet and the Conservative caucus for daring to point out the emperor’s lack of clothing. It’s clear that the Kamloops narrative has assumed almost sacred status in B.C., which means that asking questions about its veracity can destroy nearly anyone’s public career.

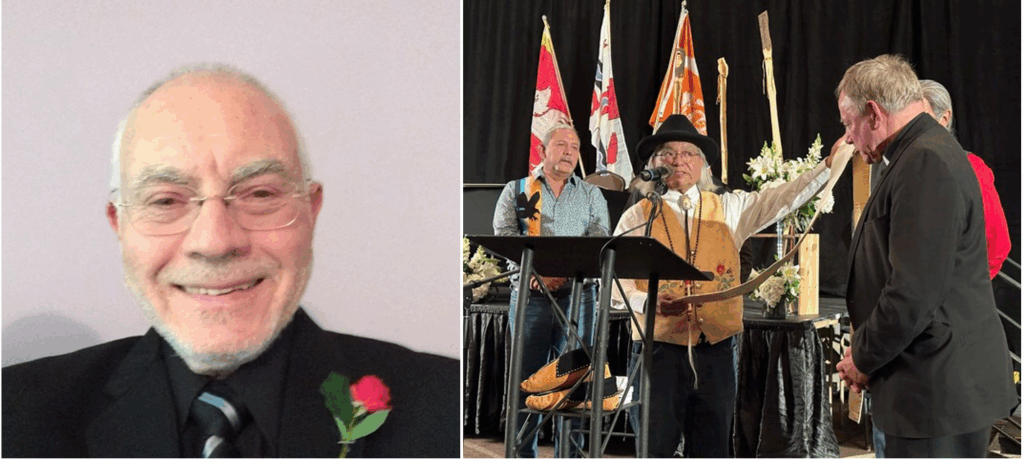

The Kamloops IRS was run by the Oblate order of the Roman Catholic Church, but you would be wrong if you thought the Church might defend the record of its missionaries against allegations of secret murders and clandestine burials. The Church’s current leaders must know the limitations of GPR and realize there is no hard evidence of crimes at Kamloops. Yet they don’t want to lose the support of their still-substantial following among the Shuswap people of B.C. The result is the “Sacred Covenant” between the Archbishop of New Westminster (i.e., Vancouver) and the Kamloops band, described for us by Hymie Rubenstein. Like politicians depending on votes, church leaders sometimes reframe historical truth when they’re trying to keep their followers’ support.

Also not to be forgotten is how the Law Society of B.C. has forced upon its members training materials that assert against all evidence the literal truth that children’s remains have been discovered at Kamloops. As told by James Pew, B.C. MLA Dallas Brodie was expelled from Opposition Leader John Rustad’s shadow cabinet and the Conservative caucus for daring to point out the emperor’s lack of clothing. It’s worth recalling that Rustad himself was expelled from the B.C. Liberal Party in 2022 for speaking the truth about a controversial subject, in his case climate change. Despite his experience, Rustad would not rise to Brodie’s defence. It’s clear that the Kamloops narrative has assumed almost sacred status in B.C., which means that asking questions about its veracity can destroy nearly anyone’s public career.

Abandon the truth: In Dead Wrong, Hymie Rubenstein (left) explains how church leaders, just like politicians, can discard the facts and reframe history to keep their followers’ support, as the Archdiocese of Vancouver did in signing the “Sacred Covenant” with the Kamloops band. (Source of right photo: Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc)

Finally, there is the story of Jim McMurtry, suspended by the Abbotsford District School Board shortly after the 2021 Kamloops announcement. McMurtry’s offence was to tell students – entirely truthfully – that while some Indigenous students did die in residential schools, the main cause was disease, particularly tuberculosis. McMurtry might have been reinstated had he made the apologies demanded of him, but he stood his ground and was fired. In Dead Wrong McMurtry pulls together some excerpts from his book The Scarlet Lesson, which when it first appeared sold so quickly on Amazon that the distributor had trouble keeping it in stock.

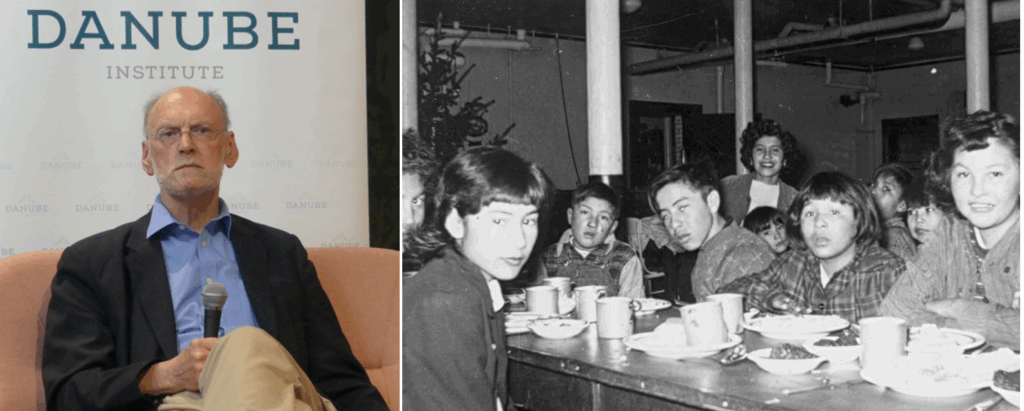

Beyond the ongoing debate over what may have happened at the Kamloops IRS, little progress has been made in rehabilitating the general image of the schools. Thus, we offer readers some evidence about life in the IRS system. Noted British historian and ethicist Nigel Biggar presents a balanced overview of the evidence in his chapter, “Residential Schools Were No ‘Atrocity’.” We are grateful to Biggar for taking the time to intervene in our Canadian debates as he is one of the world’s leading authorities on colonialism and Indigenous peoples.

What is “residential school denialism” and how is it being used?

“Residential school denialism” is a false accusation levelled by a number of Canadian NDP politicians, radical academics and Indigenous activists against anyone who criticizes or questions the dominant narrative concerning Canada’s former Indian Residential Schools, particularly claims that numerous schoolchildren were murdered and secretly buried at school sites and that remains of some of the victims have been identified. Because it aims to discourage dissent and criticism or even criminalize it (through proposed federal Bill C-413), the “denialism” narrative aims to avoid engaging with historical facts and hard evidence, while turning to state power to choke off discussion. Books like 2023’s Grave Error and its 2025 sequel, Dead Wrong, seek to head off this disturbing slide towards authoritarianism.

Historian Ian Gentles and former IRS teacher Pim Wiebel offer a richly detailed analysis of health and medical conditions in the schools. They show that these were much better than what prevailed in the Indian reserves from which most students came. There, children and adults typically lived crowded together in tents or one-room cabins with little sanitation. Tuberculosis was endemic, so that almost all children who came to an IRS were already infected. True, mortality among IRS students was higher than among other Canadian schoolchildren, but that’s the wrong comparison. The right comparison would be between enrollees in the IRS system and those who remained in their home communities, a comparison which critics of that system avoid making.

Another important contribution to understanding the medical issues is by Eric Schloss, awarded the Order of Canada for his humanitarian medical work, who narrates the history of the Charles Camsell Indian Hospital in Edmonton. The Camsell was not an IRS but its patients included many IRS students from Alberta and nearby provinces. IRS facilities usually included small clinics but students with serious problems were often transferred to Indian Hospitals for more intensive care.

Today the Camsell’s “segregated” health care is maligned; “survivors” demand federal compensation, rumours swirl on Facebook that the old site is full of “ghosts” and accusations of secret burials have been levied. The site’s redeveloper not long ago even commissioned a GPR survey to hunt for any signs, of course finding nothing. Schloss, who worked as a physician in the Camsell, describes how it delivered state-of-the-art medicine, probably better than the care available to most children anywhere in Canada at the time.

Also important in this context is an extract for the years 1946-48 from the chronicles kept by the Grey Nuns, a Canadian Roman Catholic religious order, who worked at St. Mary’s Residential School at Standoff, Alberta. It paints a revealing portrait of daily life in an IRS, vividly illustrating the care that the nuns took for the children’s well-being. The chronicles counter much of the current mythology about the IRS, describing how the children in fact could frequently return home both for short visits and longer vacations, and how their parents were repeatedly welcomed at the school for religious and secular celebrations. It also describes the wide variety of recreational events provided for the children, from movies in town to musical performances and sporting competitions.

In this vein, we should also mention the contribution by Rodney Clifton, “They Would Call Me a ‘Denier’,” which describes his experiences working in two residential schools in the 1960s as a dorm supervisor among other roles. Clifton does not tell stories of hunger, brutal punishment and suppression of Indigenous culture, but of games, laughter and trying to learn native languages from his Indian and Inuit charges.

The positive memories of Clifton and of the Grey Nuns do not mean that everything was always proper in the facilities. In a system of 143 schools spanning more than a century and educating perhaps as many as 150,000 children, there were undoubtedly many sad and even tragic occurrences, which in the current climate of opinion are endlessly re-told and re-emphasized. But recollections such as those printed here enable a more balanced understanding of what life was like in the schools.

Toronto lawyer and historian Greg Piasetzki tells the story of how “Canada Wanted to Close all Residential Schools in the 1940s. Here’s Why it Couldn’t.” For many Indigenous parents, particularly single parents and/or those with large numbers of children, residential schools were the best deal available. They offered better food, clothing and shelter than many parents could provide. They could teach reading and writing, which very few parents could do. And they were free of charge, courtesy of Canadian taxpayers and unpaid missionaries. Indian parents were often suspicious of public schools in town, fearing – correctly – that their children would be picked on there. And the IRS offered paid employment to large numbers of Indians as cooks, janitors, farmers, health care workers and, as time went on, increasing numbers of teachers and even principals.

Kimberly Murray tried to redefine ‘missing children’ to include every single Indigenous youngster who went through an IRS, Indian hospital, orphanage, prison or other institution – thus creating an agenda that could go on for decades no matter what happens to the claims about Kamloops.

Finally, Dead Wrong offers readers several articles about various topics more broadly associated with the IRS. Hymie Rubenstein describes the attacks on the reputation of the Oblate missionary Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, a towering figure of Prairie history who made immense and positive contributions, who in recent years has been denigrated because of his support for the schools.

Cosmin Dzurdzsa reviews the wave of arson against churches – the number of damaged houses of worship eventually totalling well over 100 across Canada and some of them being priceless heritage buildings – that was touched off by the false announcement of children buried at the Kamloops IRS. Shamefully, Canadian authorities have tracked down and prosecuted almost none of the arsonists.

After the Kamloops announcement Kimberly Murray, a Mohawk lawyer, was appointed “Independent Special Interlocutor” to gather information on “missing” IRS students and unmarked graves and make recommendations to the Minister of Justice. In her report to the minister, Murray tried to redefine “missing children” to include every single Indigenous youngster who went through an IRS, Indian hospital, orphanage, prison or other institution – thus creating an agenda that could go on for decades no matter what happens to the claims about Kamloops. Dead Wrong devotes a chapter by Michelle Stirling to critiquing Murray’s report.

Michael Melanson analyzes the “Land Back” movement as a force looming ominously behind agitation over the IRS. And Brian Giesbrecht takes to task lawyers who make reckless accusations and call for international investigations of the “genocide” that Canada supposedly visited upon its Indigenous peoples.

A trend in post-Second World War politics has been to expand the concept of genocide, originally coined to denote the deliberate program by Germany’s Nazi regime to destroy European Jewry, to include other atrocities which, though terrible in their own way, were not aimed at the deliberate annihilation of entire peoples. In Canada, Indigenous and other so-called progressive activists have tried to label the colonial administrations of France and Britain as genocides of native peoples. In 2015 Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission adopted the phrase “cultural genocide” to describe the IRS, inserting a deliberately inflammatory (as well as vague and confusing) term to replace what was previously described as integration or assimilation.

Indigenous and other so-called progressive activists pushed to have the treatment of Indigenous people labelled as genocide; the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (right) adopted the phrase “cultural genocide” to describe the IRS system, a deliberately inflammatory and one-sided term. (Sources of photos: (left) Wandering views/Shutterstock; (right) Mikayla Grimes/National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

Indigenous and other so-called progressive activists pushed to have the treatment of Indigenous people labelled as genocide; the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (right) adopted the phrase “cultural genocide” to describe the IRS system, a deliberately inflammatory and one-sided term. (Sources of photos: (left) Wandering views/Shutterstock; (right) Mikayla Grimes/National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)Building off these developments is Frances Widdowson’s scholarly analysis of the charge of residential school “denialism”, which is being used by true believers in the Kamloops narrative to shut down any criticism or questions. It illustrates how, in the absence of good evidence and arguments, proponents inevitably turn to the power of the state to choke off discussion. The aforementioned Murray is, not surprisingly, in the thick of the movement to condemn “denialism” – which often includes the false charge that “denialists” somehow deny that residential schools even existed.

The Kamloops narrative presented an opportunity for inflation of vocabulary with reports of secret deaths and burials to support claims of genocide. In 2022 NDP MP Leah Gazan, who has both Jewish and Indigenous ancestry, persuaded the House of Commons to give unanimous consent to a resolution on residential school genocide: “That, in the opinion of the House this government must recognize what happened in Canada’s Indian residential schools as genocide, as acknowledged by Pope Francis and in accordance with article II of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

Consent to the resolution was deemed unanimous, but it is better described by the Latin phrase nemine contra, “no one against.” Parties in the House of Commons often agree among themselves not to oppose motions of this type because they are expressions of sentiment, not binding legislation. There was no recorded vote by individual MPs.

Earlier that year, an amendment to the Criminal Code outlawed willful promotion of anti-Semitism “by denying or downplaying the Holocaust,” the latter being defined as “the planned and deliberate state-sponsored persecution and annihilation of European Jewry by the Nazis and their collaborators from 1933 to 1945.” Introduced as a private member’s bill by a Conservative MP, this legislative amendment said nothing about a Canadian genocide of Indigenous people. Still, it provided a platform for Gazan to argue that, once Parliament had recognized the existence of an Indigenous genocide, it should also move to criminalize denial of it.

What was the primary cause of death for schoolchildren at Canada’s former Indian Residential Schools?

Contrary to narratives of murders and secret burials in unmarked graves, the overwhelming historical evidence indicates the main cause of death for pupils in residential schools was disease, particularly tuberculosis. Still, health, sanitation and medical conditions in the schools were often much better than on Canada’s Indian reserves at the time, where tuberculosis was endemic, meaning many children probably arrived at school already infected. Students with serious problems were often transferred to specialized care such as the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton, Alberta, which delivered state-of-the-art medicine for the time, as recounted by a former Camsell Hospital physician in the book Dead Wrong (published in November 2025).

On September 26, 2024, Gazan took the next step by introducing a private member’s bill, C-413, to further amend the Criminal Code:

“Everyone who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, willfully promotes hatred against Indigenous peoples by condoning, denying, downplaying or justifying the Indian residential school system in Canada or by misrepresenting facts relating to it

(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.”

This bill failed to pass, but Gazan reintroduced it in the new Parliament of 2025. Had these sorts of provisions been in force back in 2021, it might well have become a crime to point out that the Kamloops GPR survey had only identified soil anomalies rather than buried bodies. But “anomalies” is now the band chief’s own public position, illustrating the situation’s absurdity. Would an Indigenous leader now be accused of “denialism” by Murray or Gazan? Or, now that the term “anomalies” has been deemed acceptable, would critics who were previously maligned (and perhaps charged and even imprisoned) be pardoned and financially compensated?

As the proponents of the Kamloops narrative have failed to provide any convincing hard evidence for it, they are trying to mobilize the coercive authority of the state to stamp out dissent.

While the wheels of legislation and litigation grind and spin, those who wish to limit open discussion of residential schools in general and the Kamloops narrative in particular have developed a formidable rhetorical strategy around “denialism”, drawn from the earlier debates about the Holocaust. Murray Sinclair, the Chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for example, labelled Senator Lynn Bayek a “denier” because she had maintained that residential schools had done some positive things. Sinclair portrayed Bayek as slow-minded, dim-witted and delusional.

The most energetic academic purveyor of the “denialism” concept is Sean Carleton, a self-proclaimed “settler scholar” and associate professor of history and Indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba, who defines it as the “the rejection or misrepresentation of basic facts about residential schooling to undermine truth and reconciliation efforts in Canada.” He has been so successful in propagating the term that the invocation of “denialism” has become a routine rhetorical move in the legacy media to avoid questions of fact and logic.

Most of what is written by Carleton and other proponents of the denialism trope follows Sinclair’s ad hominem path. Almost never is there factual engagement on the question of whether children were clandestinely murdered and buried at Kamloops. As the proponents of the Kamloops narrative have failed to provide any convincing hard evidence for it, they are trying to mobilize the coercive authority of the state to stamp out dissent.

In addition to providing the public with critical facts, information and context about this contentious and influential issue, one of the main hopes behind publication of Dead Wrong is to help head off this ominous move toward authoritarianism.

Tom Flanagan is the author of many books on Indigenous history and policy, including the best-selling Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us and the Truth About Residential Schools, which he co-edited with C.P. Champion.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.