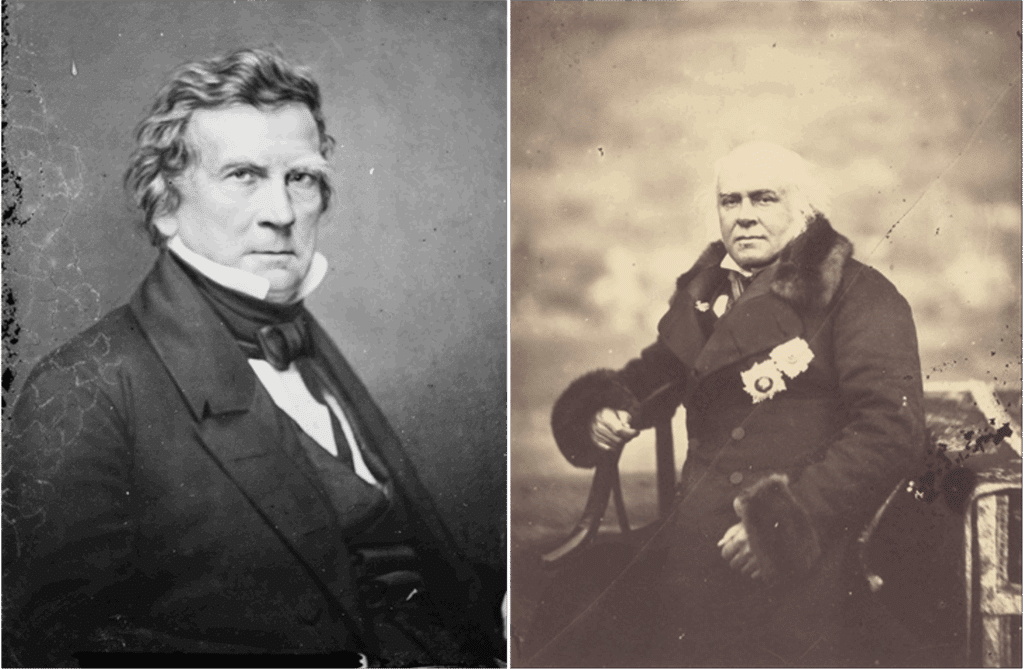

There was free trade between the United States and Canada before there was a country called Canada. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 came into force 13 years prior to Confederation. Also known as the Marcy-Elgin Treaty after chief negotiators William L. Marcy, the U.S. Secretary of State, and Lord Elgin, Governor-General of British North America, it enabled bilateral free trade in raw and lightly-refined goods including meat, grains, vegetables, tobacco, coal, pitch, tar and lumber. Mutual fishing rights were also included.

According to Canadian historian D.C. Masters, the agreement was “a skillfully drafted compromise” that set off a tremendous economic boom throughout British North America, which then consisted of the United Province of Canada (Ontario and Quebec) plus New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Prior to the treaty, cross-border commerce stood at $18.9 million; in 1855 it shot up to $42.8 million and by 1866 had more than tripled to $73.3 million. While this was a period of rising prosperity throughout the young continent, the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) played a significant role in boosting demand for Canadian goods. Then politics got in the way.

The treaty was set to last for a minimum of 10 years, after which it could be revoked by either party on one year’s notice. As soon as the Civil War was over the U.S. government exercised its right to kill the deal. Northern resentment over Great Britain’s perceived support for the Confederacy was a factor. But, as historian Masters points out, “The real foundation of the opposition [to the treaty] was protectionism opinion.” In the post-war period, American farmers and industrialists saw no need to trade with the Canadian provinces when they could supply the needs of their newly re-unified country by themselves.

“A skillfully drafted compromise”: The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State William L. Marcy (left) and Lord Elgin, Governor-General of British North America (right), established a lucrative free-trade regime between the United States and Great Britain’s Canadian colonies 13 years prior to Confederation.

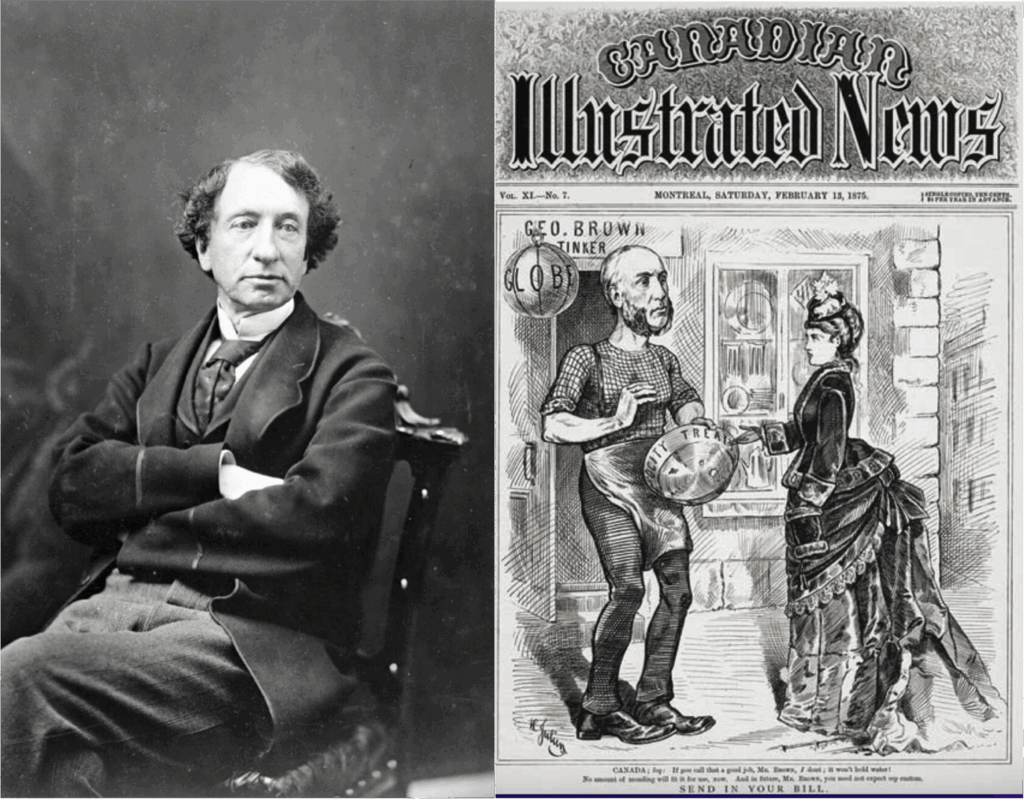

“A skillfully drafted compromise”: The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State William L. Marcy (left) and Lord Elgin, Governor-General of British North America (right), established a lucrative free-trade regime between the United States and Great Britain’s Canadian colonies 13 years prior to Confederation.Once the treaty was revoked in 1866, trade dropped sharply, triggering a “Canadian business crisis” – an economic calamity that lent immediacy to the gathering Confederation movement. After the events of 1867 established the new country, Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, tried repeatedly to reach another trade deal with his neighbours, without success. Eventually he pivoted away from free trade and embraced his own version of protectionism.

Following the 1878 federal election, Macdonald introduced his famous National Policy that saw Canada turn inward with steep tariffs and other barriers to trade. While politically popular at the time, Macdonald’s National Policy is now regarded as disastrous economic policy because of its role in raising prices, limiting competition and slowing the development of Western Canada. Academic studies have since found it to be responsible for a loss of between 4 percent and 8 percent of Canada’s GDP.

After the Americans revoked the Marcy-Elgin treaty in 1866, Canada’s first Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald (left) repeatedly tried to reach another trade agreement with the U.S. When that failed, he introduced his own protectionist National Policy in 1878. At right, the cover of Canadian Illustrated News depicting “Miss Canada” returning a broken pan labelled “Reciprocity”. (Source of right photo: Library and Archives Canada)

After the Americans revoked the Marcy-Elgin treaty in 1866, Canada’s first Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald (left) repeatedly tried to reach another trade agreement with the U.S. When that failed, he introduced his own protectionist National Policy in 1878. At right, the cover of Canadian Illustrated News depicting “Miss Canada” returning a broken pan labelled “Reciprocity”. (Source of right photo: Library and Archives Canada)This narrative arc of the Marcy-Elgin Treaty – a mutually-beneficial trade arrangement that came undone due to American political eruptions and was then made worse by reflexive Canadian economic nationalism – has set the pattern for Canada-U.S. trade relations across the ensuing 171 years.

And here we go again.

The Protectionist Merry-Go-Round

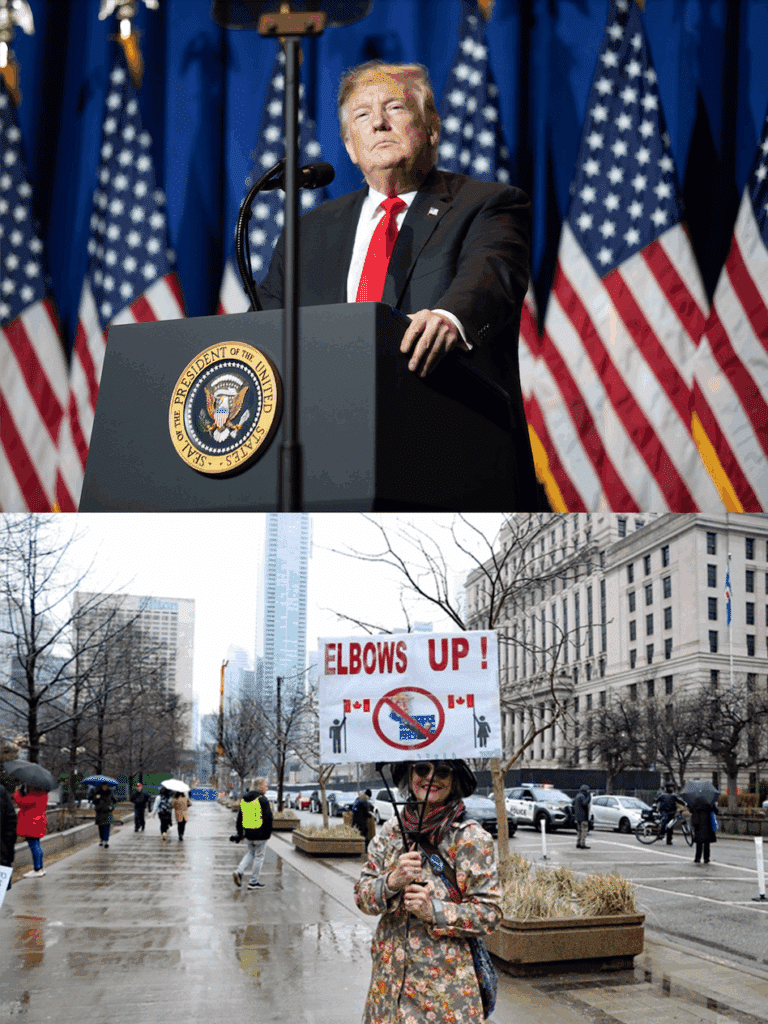

U.S. President Donald Trump’s America First Trade Policy, formally launched as soon as he took office in January, has upended world trade by imposing substantial tariffs on imports from nearly all countries. In Canada, long considered America’s closest ally and best trading partner, the initial imposition of 25 percent tariffs despite the presence of the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA, the successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA), was seen as a deep insult as well as an economic nightmare. With Canadians having enjoyed free trade with the U.S. since 1989, any restriction to that access is now considered a serious provocation.

‘For most of Canadian history,’ observes Asa McKercher, ‘there has been this merry-go-round of alternating protectionism and openness from the U.S., which leads to a subsequent Canadian response.’

The new Liberal government of Mark Carney quickly retaliated with counter-tariffs, leading to a further response from the White House. Additional moves included on-again, off-again “grace periods” or deferrals of certain tariffs by Trump, plus new threats and the quiet exemption of all items previously covered by CUSMA. Amid all the chaos and uncertainty, a wave of economic and political nationalism has swept across Canada. As the 2025 federal election campaign unfolded, for example, voters told pollsters that the ability to stand up to Trump had suddenly become a key factor in their voting intentions. Such sentiment handed a surprising win to Carney, who made much of his plans to get tough with the U.S. President.

Consumers similarly vowed to punish their American neighbours with “Buy Canadian” pledges and a boycott on American travel. “Elbows Up!” became a national catch-phrase. When Statistics Canada reported Canada’s trade with the U.S. in May had slipped to 68.3 percent of total exports, down from the 2024 average of 75.9 percent, headlines such as “Canadians begin to diversify trade” and “Efforts to broaden trade in Canada working” treated it as a reason to celebrate, since it suggested the country was moving past its dependency on those nasty Americans. For most Canadians, the Trump tariff war is the biggest disruption in Canada-U.S. relations they’ve ever experienced. And many seem determined to make their neighbours suffer for it.

Among those with a longer perspective, however, the recent ructions are just one more episode in a long-running economic soap opera that began way back in 1854. “For most of Canadian history,” observes Asa McKercher, “there has been this merry-go-round of alternating protectionism and openness from the U.S., which then leads to a subsequent Canadian response.” McKercher is a political scientist specializing in Canada-U.S. relations at the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

For reasons of geography, culture, language and economics, there’s tremendous logic in facilitating the freest possible trade between Canada and the U.S., McKercher says in an interview. But politics has a habit of getting in the way. In 1910, for example, Republican President William Howard Taft put aside his country’s protectionist tendencies and negotiated a new reciprocity treaty with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government. But Laurier was defeated by the anti-free-trade Conservatives in the 1911 federal election and the treaty was never implemented. Canadian voters were in another of their anti-American moods.

In the early days of the Great Depression, Canadians were suddenly feeling more amenable to trading across the border when the U.S. shifted back into protectionist mode with its infamous Smoot-Hawley tariffs. Then in 1948, the Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King negotiated yet another free trade deal with the Americans but King, on the verge of retirement, spiked the deal for fear his successor Louis St. Laurent would suffer the same fate as Laurier in 1911.

Back and forth trade relations between Canada and the U.S. have gone, with the U.S. typically setting the pace. It is a rich historical record that offers many valuable lessons for today. And perhaps the best source of advice on how Canada should respond to the chaos of Trump’s current tariff shocks can be found in what historians today call the “Nixon Shocks”.

Birth of the Third Option

In the early 1970s, U.S. President Richard Nixon was dogged by a new economic malaise termed “stagflation” – stagnant economic growth combined with high inflation – arising from the U.S. government’s enormous spending on the Vietnam War and numerous misguided domestic policies. In response to this erosion in America’s financial might, Nixon upended the global economic status quo with his New Economic Policy. This included taking the U.S. dollar off the gold standard, ending the Bretton Woods fixed-exchange rate system, instituting wage and price controls and imposing a 10 percent tariff on all imports.

To Canada’s shock and horror, it too was subjected to Nixon’s tariffs. During the postwar period Canada and the U.S. had once again been slowly embracing freer trade; the 1965 Auto Pact, for example, allowed automobiles and automotive parts to flow across the border duty-free and is often considered a precursor to later free trade deals. Nixon’s move thus constituted a serious break in Canada’s improved access to the U.S. market and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau argued vigorously for an exemption. But like his predecessor Macdonald in the 1860s, Trudeau was unsuccessful.

The Nixon Shocks “served as a reminder of how Canada was reliant on America in such a big way,” says McKercher, acknowledging the obvious parallels with today’s situation. “And that gave rise to the idea that we shouldn’t rely so heavily on the U.S. anymore.” In 1972, Liberal cabinet minister Mitchell Sharp released a white paper outlining three possible reactions to the Nixon Shocks. First was to maintain the status quo. Second, to seek even stronger economic relations with the U.S. And third, to look elsewhere. The Trudeau government found the final choice, what came to be known formally as the Third Option, to be the most attractive and pursued it aggressively.

The Third Option’s overarching objective was to sever Canada’s deep economic and cultural ties with the U.S. It didn’t work.

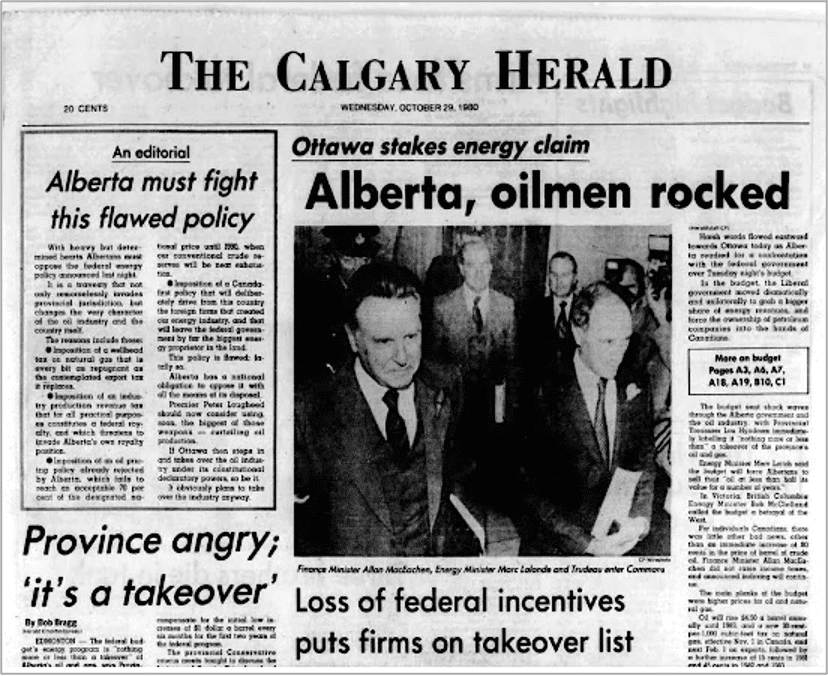

As McKercher explains, the Third Option involved more than just a shift away from the U.S. in terms of commerce. In addition to seeking out other countries to serve as trade “counterweights” to the mighty U.S. economy, “Trudeau also sought to expand political and cultural relations with many other countries, including Communist countries in Eastern Europe and elsewhere,” he says. “There was a big emphasis on China, Cuba and the Soviet Union.” At home, the Third Option gave birth to many aggressive protectionist policies aimed at keeping the Americans at bay, including the Foreign Investment Review Agency and National Energy Program which, in turn, fomented Western separatism. “These were policies specifically meant to discourage foreign investment in Canada,” explains McKercher, describing them as “self-inflicted harms.” Trudeau’s insular push signalled another of Canada’s periodic eruptions of economic nationalism and anti-Americanism, with the hard-left NDP frequently egging him on.

Blind alley: In response to the Nixon tariffs, the Trudeau government attempted to reduce Canada’s reliance on the U.S. through its “Third Option” policies that included the Foreign Investment Review Agency and National Energy Program (NEP). Shown, the front page of the Calgary Herald on October 29, 1980 following the NEP’s introduction, which greatly exacerbated western Canadian alienation.

Blind alley: In response to the Nixon tariffs, the Trudeau government attempted to reduce Canada’s reliance on the U.S. through its “Third Option” policies that included the Foreign Investment Review Agency and National Energy Program (NEP). Shown, the front page of the Calgary Herald on October 29, 1980 following the NEP’s introduction, which greatly exacerbated western Canadian alienation.The Third Option’s overarching objective was to sever Canada’s deep economic and cultural ties with the U.S. It didn’t work. Throughout the 1970s, the share of Canadian exports delivered to the U.S. never dropped below 65 percent. By the early 1980s, it was well over 70 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of exports directed towards other countries barely budged. There was no diversification of Canada’s export trade in spite of all the self-harm caused by policies such as the NEP. In fact, foreign direct investment from the U.S. actually increased over this time, as did Canadian investment in the U.S.

Today, the Third Option is widely acknowledged as being a complete failure. “As much as the government wanted to expand relationships elsewhere, the private sector did not,” says McKercher. “Like any government initiative, it couldn’t change basic facts. And the pull of geography is really, really strong.” The Canadian business community maintained its tight focus on the U.S. because doing so made the most sense, regardless of what Ottawa thought. As for Trudeau’s attempted courtship of Western European democracies and Communist dictatorships in Eastern Europe and Asia, none ever showed any serious interest in free trade with Canada.

Second Option Gets a Second Chance

The Pierre Trudeau government’s unwavering commitment to the Third Option throughout the 1970s not only failed to diversify Canada’s economy and spurred-on Western Canadian alienation, it also precipitated Canada’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Amidst the lengthy 1981-1982 recession, however, there appeared a ray of hope. In 1982 Trudeau set up the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada headed by former finance minister Donald S. Macdonald. The commission was to investigate all aspects of the Canadian economy and deliver advice on how to “respond to the challenges of rapid national and international change in order to realize Canada’s potential.” Such a sweeping mandate can be seen as tacit admission of how badly the country’s existing policy mix had failed.

By the time the Macdonald Commission reported, three years and 75 volumes later, Trudeau was no longer prime minster. It was thus up to Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney to accept the Commission’s recommendations, which included a comprehensive repudiation of the Third Option and the promotion of much closer integration with the U.S. via a free trade agreement – what was once considered the second of Sharp’s three options. All this was based on well-documented and irrefutable economic evidence. “Geography, combined with similar cultural and ethnic backgrounds has given rise to an interrelationship between the…Canadian and U.S. economies,” the Macdonald Commission’s final report stated. “This interconnection is immeasurably more extensive than Canada’s relationship with any other country or group of countries. Canadian economic well-being thus depends substantially on our relations with the United States.”

To his credit, Mulroney set aside his party’s old animus towards free trade and entered into negotiations with U.S. President Ronald Reagan. The result was the 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA, passed and ratified in Canada in late 1988, following a bruising federal election campaign) and in 1993 NAFTA, which encompassed Mexico as well. The experience has been unquestionably positive for Canada.

Five years after the signing of the FTA, bilateral trade with the U.S. was up by a third; after ten years, it was up over 140 percent. While some domestic industries formerly protected by the remnants of Macdonald’s centuries-old National Policy were hit hard by the changes, many more new industries sprang up to take their place. Perhaps the biggest advantage was a “spectacular” improvement in Canada’s labour productivity brought on by the newfound competition, investment and openness. This success encouraged subsequent federal governments to sign free trade deals with other countries, including Israel, Chile, South Korea and Great Britain, although none of these later deals compare in significance to the original FTA.

“Mulroney made the bet to align Canada with a booming U.S. economy under Reagan. And it was a pretty good bet to make,” says McKercher, citing the tremendous economic advantages that have arisen as a result of free trade. The lesson? “We will never get away from the U.S. economy. Nor should we want to.”

What makes Canada-U.S. trade so hard to replace?

Friends No More

Despite the wisdom of the Macdonald Commission and the many benefits it wrought, the 2025 Trump tariffs have abruptly brought discredited Third Option attitudes back to life. “Our old relationship with the United States, a relationship based on steadily increasing integration, is over,” Carney declared during his election victory speech in April. He followed up this eulogy on Canada-U.S. relations with concrete action, including efforts at “recalibrating” relations with China in hopes of gaining greater trade traction to replace the U.S. market.

Carney also jetted to Brussels to sign a defence procurement and rearmament agreement with the European Union, a body that has almost no role to play in Canada’s immediate national security concerns. While in Europe, Carney again sought to emphasize his newfound distance from the U.S. with the curious claim that “Canada is the most European of non-European countries.” Such an allegation is highly debatable, given the “Euro-ness” of New Zealand and Australia, as well as Chile, Colombia, Argentina and many other Spanish-speaking nations. What seems far more certain is that Canada is still the “most U.S. of non-U.S. countries”.

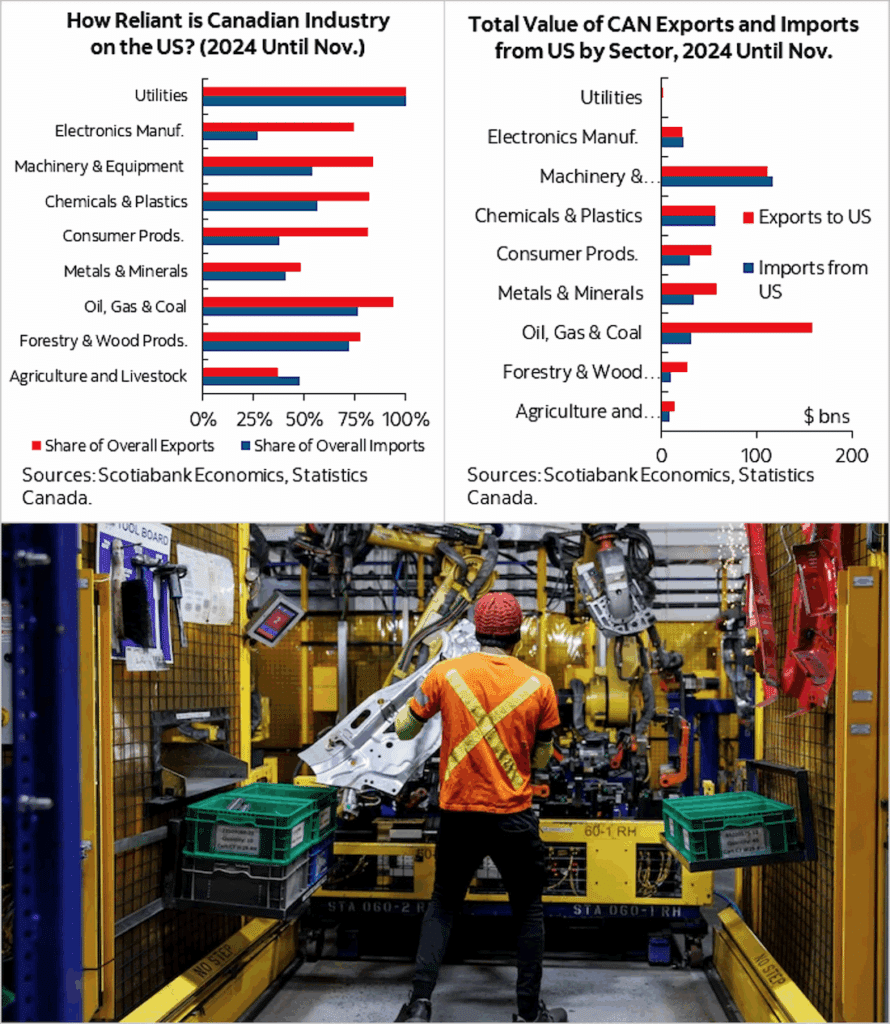

Regardless of the Prime Minister’s posturing, the fact remains that even after the Trump tariffs, the U.S. still accounts for more than two-thirds of Canada’s entire export market; China represents less than 4 percent.

At home, Carney has sent mixed signals on trade. He wisely dropped his government’s much-maligned Digital Services Tax (DST) when Trump complained about it. And since the G7 meeting in Kananaskis, he has said repeatedly that Canada will sign a new trade deal with Trump by the end of July. But Carney has also pursued other deliberately provocative protectionist policies that harken back to Pierre Trudeau’s failed Third Option efforts such as FIRA and the NEP. Most strikingly, his government passed the Bloc Québécois’ Bill 202 that shields Canada’s inefficient and self-harming supply management system for dairy, egg and poultry producers from all future trade negotiations. There is simply no way to reconcile such a move with a commitment to open borders or free trade. Like the DST, supply management is a major irritant for Trump.

“It’s shocking,” says Martha Hall Findlay of the Carney government’s unswerving commitment to Canada’s comparatively small dairy sector, a move that risks imperilling the country’s broader and vastly larger trade interests – including far more valuable segments of the agriculture sector. Hall Findlay is the director of the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and a former Liberal MP. “Supply management is bad for the economy,” she says bluntly. While she admits it is popular right now for Canadian politicians to be seen thumbing their noses at Trump, the dairy controversy reveals “an incredible lack of political leadership. Mark Carney is eventually going to have to deal with this.”

Regardless of the Prime Minister’s posturing, the fact remains that even after the Trump tariffs, the U.S. still accounts for more than two-thirds of Canada’s entire export market; China represents less than 4 percent. It is impractical to the point of delusional to think Canada could ever replace its U.S. trade with another country or trading bloc. This includes proposals such as the Canada-Australia-New Zealand or “CANZUK” alliance that was discussed in a previous instalment of this special series on restoring Canada.

“We need to recognize that we are very dependent on the U.S.,” says Hall Findlay. “It will always make far more sense to trade with the Americans than anyone else,” agrees McKercher, casting a glance back through Canada’s trade history with the U.S., from the highs of the Marcy-Elgin Treaty and FTA to the lows of the Nixon and Trump shocks. “They are the world’s biggest economy and they are right there, beside our border. Any policy that tries to cut us off from the American market is doomed to failure.”

How did the recent Trump tariffs affect Canada, even with CUSMA in place?

What Now?

Accepting the vast weight of historical and economic evidence that Canada’s best interests lie in maintaining a copacetic trade relationship with the Americans, the current situation presents a real dilemma for practical-minded Canadian policy-makers. A return to Third Option-style isolationism may be popular with pundits, but will leave Canadians as a whole worse off in the long-run. Every Canadian export sector with the exception of agricultural products and minerals depends on the U.S. for at least three-quarters of its sales. Two million Canadian jobs also depend on the American market, with over half of them in the country’s manufacturing sector centred in Ontario and Quebec. There is no getting around these facts.

Further, experience suggests the U.S. will eventually return to its senses and embrace a freer trade regime at some point – higher tariffs mean higher prices and less choice for American consumers, after all. But such a thing seems unlikely in the near term, given Trump’s determination. So what should Canada do in the meantime?

Hall Findlay, who is also a member of the Expert Group on Canada-U.S. Relations organized by Carleton University and the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, advocates a multi-track response. Acknowledging the inescapable gravitational pull of the American market, she recommends Canada make common cause with the many American businesses and interest groups that understand the true significance of trade between the two countries, particularly in border states. “As much as Canadians may enjoy going ‘elbows up’ and not flying to Florida, it will be [those] Americans who are hurt the most by these tariffs who will eventually fix the problem,” she says.

Hall Findlay also accepts the need to look elsewhere for new trade opportunities. Then again, that’s good advice at all times. “We certainly don’t need a Trump shock to promote greater trade” with other countries, she quips. Recall that in the ten years following the FTA’s implementation, Canada’s bilateral trade with the U.S. grew substantially, as would be expected. But as economist Daniel Schwanen wrote for the Institute for Research on Public Policy in 2004, “Canada’s [trade and investment] relationships with the rest of the world in some cases grew even faster” over this time. The reason, as previously discussed, is that the entire Canadian economy became more productive and trade-focused in the wake of the challenges and opportunities presented by the FTA. And this had an effect far beyond exports to just one country.

Reminiscing about Canada’s past export successes brings up Hall Findlay’s final major issue: Canada is not the trading nation it used to be. “We have a stumbling economy,” she warns. Across a wide range of key economic indicators, Canada’s performance is dismal and has been for a decade or more. “Our productivity is crappy, our living standard and growth figures are also poor compared to the U.S. We are simply not doing very well in any of these areas. And we can’t blame Donald Trump for that.”

Are We Still a Trading Nation?

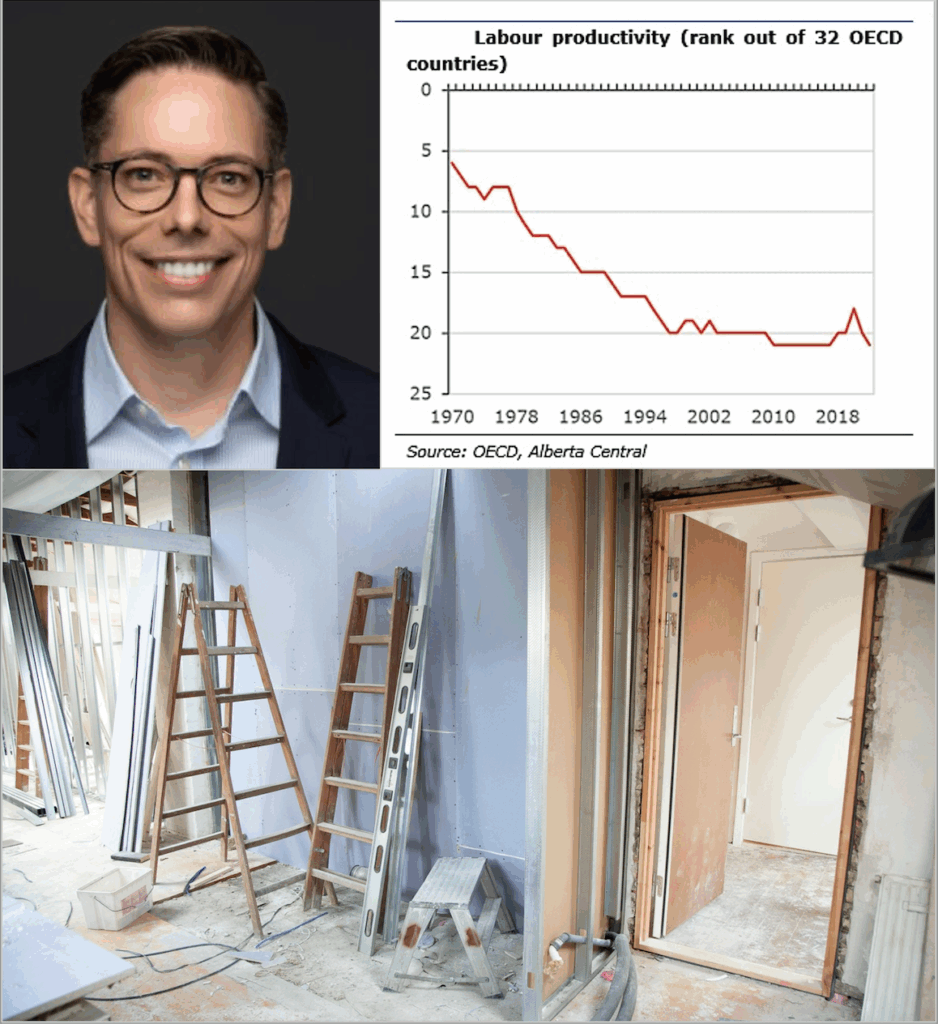

Canada’s productivity crisis has been much discussed in recent years – in 2024 the Bank of Canada called it a “break-the-glass” emergency – but it has yet to be addressed in any significant way. Charles St. Arnaud, chief economist at Alberta Central, the trade association for the province’s credit unions, has authored several recent research reports charting the gradual decline in Canada’s productivity and trade competitiveness over the past several decades, and the reasons behind that phenomenon.

“Canada once had the sixth-highest level of labour productivity in the OECD,” says St. Arnaud in an interview. “Now it ranks 22nd.” Canada lags not just the mighty U.S. in this measure, but many smaller countries such as Australia, Sweden and Denmark. And the rot seems to be everywhere. Noting that skillful managers are one key to improving productivity, a recent OECD report frets that the “quality of management of Canada’s manufacturing firms is…well behind the U.S.” Of even greater concern than managerial expertise is the scope and scale of investments in machinery, equipment and intellectual property (ME&IP), all of which form the foundation for a healthy, productive economy. The total for this metric peaked in Canada in 2008 and has been falling ever since.

According to St. Arnaud’s calculations, Canadian house-flipping activity (including renovations and ownership transfer costs) is now nearly equal to annual expenditures on ME&IP. “We are no longer investing in productive assets,” he says with concern. “Household borrowing has crowded out private investment.”

The growing significance of the housing market signals a profound shift in the Canadian economy from its earlier focus on export markets to that of domestic consumption. Between the 1960s and the 1990s, St. Arnaud calculates exports contributed approximately half of the growth in per capita GDP. Since the 2000s, that share has fallen to zero. Given this, he asks, “Can we even still call ourselves a trading nation?”

As St. Arnaud explains it, Canada “became complacent about our place in the global trading system over the past decade because we had the biggest consuming nation in the world at our doorstep.” Now that this relationship has been imperilled, Canada needs to find its footing as a trading nation once more. “We will always be integrated with the U.S. in some fashion,” he notes. “But we need to prove we can still be competitive.”

How is Canada’s productivity crisis tied to the Trump tariffs?

Another Macdonald Commission Moment

As the saying goes, every crisis contains an opportunity. And given the slow but inexorable decline in Canada’s productivity, the Trump tariffs offer the chance to make a much-needed course correction. What Canada needs, in essence, is another Macdonald Commission moment – the decisive enunciation of a new vision for Canada that breaks sharply with the presiding ideology. In our current case, this refers not to Pierre Trudeau’s disastrous Third Option policies, but to those of his son, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who focused less on currying favour abroad and more on celebrating excess at home with a panoply of indulgent social policies. It should also be possible to achieve such an epiphany without the need for three years of research, given that the Macdonald Commission’s conclusions still hold relevance today.

Wherever the spark comes from, the goal should be to use the current break in our relations with the U.S. to retool the Canadian economy and fix our flagging productivity.

One possibility for jump-starting a national conversation on economic matters is Canada’s Productivity Initiative, a series of six conferences organized by Hall Findlay’s School of Public Policy and funded by the Alberta government. Topics include tax reform, competition policy, immigration and natural resource development, and all prompt common-sense economic suggestions that are largely in line with what the Macdonald Commission uncovered over 40 years ago. “Any political decision-maker with a sense of history will already know the lessons,” Hall-Findlay says. “We have talked about productivity for ages. It is time to do something about it.” Other think tanks and financial organizations are similarly at work ringing alarm bells and offering concrete policy suggestions to Ottawa on productivity matters.

Wherever the spark comes from, the goal should be to use the current break in our relations with the U.S. to retool the Canadian economy and fix our flagging productivity. While this repair job will not be painless, the current bout of “Elbows Up!” patriotism, general acceptance that some economic hardship is in the offing because of the tariffs and a ready-made villain in Trump mean Canadians as a whole may be more accepting of short-term discomfort than they normally would be.

The current confluence of events thus offers a unique opportunity to make some tough choices across a wide range of policy areas. Here we can include lowering taxes and simplifying the tax code to encourage investment and risk-taking, improving the country’s basic infrastructure, paring back environmental and other regulations, curtailing social welfare programs, promoting competition and managerial skills, pushing back against Indigenous veto-seeking and all the other potentially unpopular but necessary things required to make Canada a highly-productive and flourishing trading nation once more. While Carney has proposed to do some of these things for a handful of “nation-building” mega-projects that meet his personal favour under Bill C-5, which includes the Building Canada Act, these reforms need to be implemented on an economy-wide scale and without political micro-management. As soon as possible.

“Hopefully this is a wake-up call for people to realize that industry and investors need to do more, and governments need to do less,” says McKercher. Whether this task falls to the current government or its eventual successor remains to be seen.

The proper response to the Trump tariffs is thus not to invent new ways to hate Americans or to engage in vain attempts at reducing the vast array of goods and services that move across the border on a daily basis. Like tempestuous siblings, Canada and the U.S. are connected in ways that can never be undone – and it is sheer folly to argue otherwise. Rather, Canada should take this time to consider its own flaws and fix what is broken. Only once our house is back in order can we consider ourselves ready to take full advantage of the American market when the opportunity for freer trade returns. And based on 171 years of experience, we can be sure it will.

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior features editor at C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.