[Editor’s Note, September 12, 2025: A previous version of this article contained incorrect information; four sentences were subsequently deleted or modified. C2C regrets its error.]

Birju Dattani seemed the ideal candidate to head the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC). We know this because the June 14, 2024 press release from Liberal Justice Minister Arif Virani explained that Dattani had been chosen through a “rigorous, open, transparent and merit-based selection process” to be the CHRC’s next Chief Commissioner. Dattani would be the first Muslim and first “racialized person” to head the federal organization dedicated to protecting the rights of all Canadians. Perfect.

The only problem with this otherwise masterful plan was that Dattani had an alias the government didn’t know about. As “Mujahid Dattani”, he had posted and shared numerous controversial opinions about Israel and its conflict with the Palestinians. Dattani has also written about and spoken at events addressing Israel, and Middle Eastern affairs and politics. Some of those events also included sessions on Israeli “apartheid” (a calumny against a country that extends full rights to its Arab, Druze and other minorities) and the role of terrorism in furthering political objectives.

None of this was revealed by the federal government’s rigorous, open, transparent and merit-based selection process. It only came to light following due diligence by the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs and other Jewish organizations which then made their intelligence available to the national media. Dattani’s unsuitability for the post was worsened by his appointment coinciding with the Justin Trudeau government’s introduction of Bill C-63, the since-deceased Online Harms Act, which would have given the CHRC Chief sweeping powers to police online postings to stamp out “hate”, however defined.

During a subsequent federal investigation into how he came to be hired, Dattani was asked why he used the nom de plume Mujahid when expressing controversial opinions or participating in anti-Israeli events. He claimed it was merely “whimsical”. Dattani’s appointment was supposed to take effect on August 8, 2024, but he went on leave one day prior and then resigned on August 12 without ever having worked at the position. (Curiously enough, he later claimed to be the “former Chief of the Canadian Human Rights Commission”.)

How did someone so obviously wrong for the top job at the CHRC get selected in the first place? The answer seems obvious. As a Muslim and self-identified “racialized person”, Dattani ticked some very big boxes for a Justin Trudeau government obsessed with identity politics and Islamophobia. Whether Dattani was actually qualified was irrelevant; his appointment felt right. That uncovering the huge problems with his candidacy was left to Jews – a group that has long experienced religious discrimination and hatred – further highlights the enormous flaws in how human rights are defined and adjudicated in this country.

Feelings, Nothing More Than Feelings

Dattani’s tale is just one of many, many examples of the rot throughout Canada’s human rights industry. Rather than delivering on their fundamental obligation to protect the individual rights of all Canadians, the nationwide superstructure of human rights tribunals and commissions has instead become obsessed with the politics of identity and the invention of obscure new rights that further such activism. Significantly, it is the feelings of alleged victims, and not the objective truth, that matter these days.

A few examples of this fixation. Last month the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal awarded $10,000 to a man who was dismissed after a week on the job due to his own incompetence. After telling him he was fired, his employers then discovered he had not been truthful about his real identity and that he’d once been convicted of bank robbery. According to the provincial tribunal, the mere fact his past conviction was mentioned by his employers on his way out the door entitled him to a $10,000 cash award. No actual discrimination was ever proven as he’d already been fired when the alleged offence took place. Nonetheless, his employer had to pay for hurting his feelings.

The CHRC recently invented the new complaint of “flying while black” to rationalize siding with a woman who claimed she’d been discriminated against when she attempted to cut into another line at a busy Air Canada check-in counter at the Vancouver International Airport and was rudely rebuffed by an attendant, whom she identified as “Asian”. There’s no proof her race or that of the attendant had anything to do with how she was treated. This case additionally raises the odd – and entirely counter-factual – notion that a stress-free boarding experience is a human right. And in Ontario, a small-town mayor was fined for not proclaiming Pride Month, the provincial human rights tribunal declaring the Emo township municipal council’s democratic vote to be “discriminatory” because the mayor was “demeaning and disparaging” to the activists who demanded he fly their flag. In other words, he hurt their feelings.

Even in losing causes, the human rights apparatus seems determined to defend the feelings of its clients. The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission once pursued a case for four years regarding an atheist who felt offended at having to hear a Christian prayer at a public meeting. Although the case was finally and properly dismissed, since no discrimination ever occurred, the adjudicating tribunal in a final jab still declared the prayer “disrespectful”. In Nova Scotia, the human rights commission has even declared an interest in how people dress up on Halloween, with a video admonishing residents not to wear sombreros or wigs to parties for fear someone somewhere might not like it.

The rot runs deeper than this fixation with feelings, however. The human rights industry at times appears committed to eradicating – rather than protecting – the most fundamental rights guaranteed to Canadians. Beyond frequent and alarming intrusions against freedom of speech, a bizarre 2023 CHRC discussion paper on religious intolerance singles out Christianity as an example of “systemic religious discrimination.” Rather than protecting religious freedom, as is its statutory obligation, the CHRC openly criticizes Canada’s most widely-practised religion. “Statutory holidays related to Christianity, including Christmas and Easter, are the only Canadian statutory holidays linked to religious holy days,” the paper reads. That “non-Christians may need to request special accommodations to observe their holy days” is thus presented as evidence of discrimination. But it actually indicates the opposite: accommodation for religious minorities is already protected by law.

While the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights represented a necessary kick in the pants for Third World dictatorships or European countries that had acquiesced to the boot heel of fascism, Canada already had a system for protecting the basic rights of Canadians – long before the UN even existed.

The same paper offers a long and familiar list of traits that it claims are associated with historical acts of discrimination in Canada: “white, male, Christian, English-speaking, thin/fit, not having a disability, heterosexual, gender conforming.” All such people are unfairly smeared as being intolerant, hardly the sort of thing one would expect from an organization supposedly dedicated to preserving the rights of everyone, even those in the majority.

How did this happen? And how can we fix it?

How has the rise of identity politics influenced bodies like the Canadian Human Rights Commission?

The “Rights Revolution” Comes Calling

To hear advocates tell it, Canada was late to the party on human rights. According to Stephen Heathorn and David Gouter in their 2013 book Taking Liberties: A History of Human Rights in Canada, “Canada was surprisingly slow to adopt the rights revolution…given concerns that existing norms and liberties could conflict with these new universal rights.” For Heathorn and Gouter, the starting point of the global “rights revolution” is the 1948 signing of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

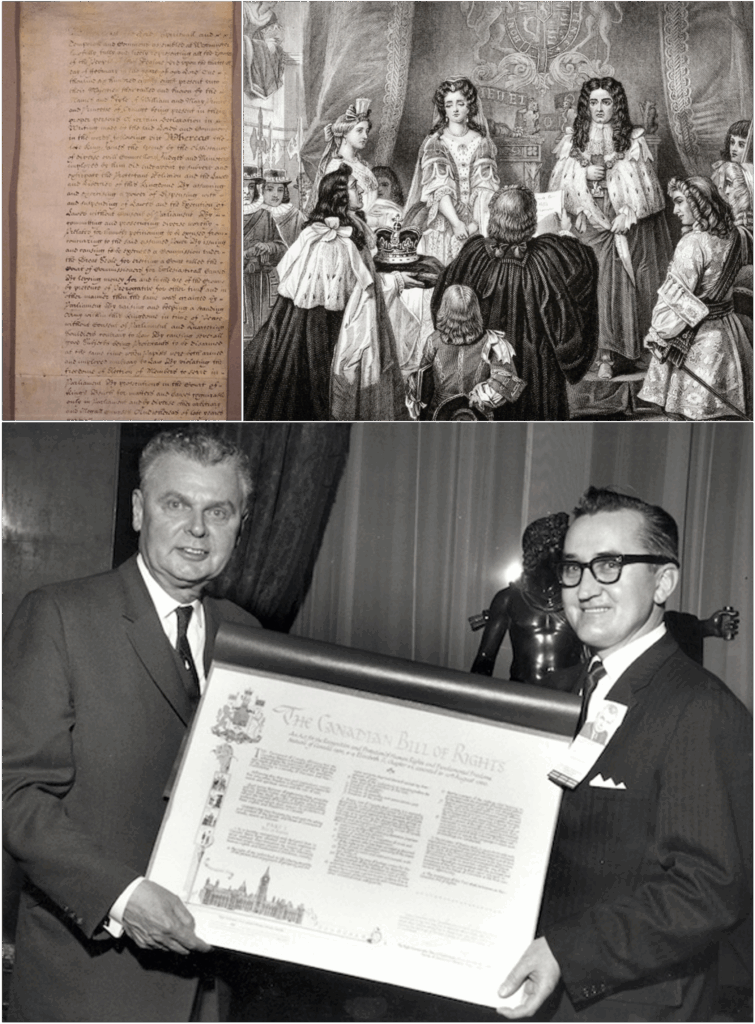

Yet while the UDHR represented a necessary kick in the pants for military dictatorships in the Third World or certain European countries that had willingly acquiesced to the boot heel of fascism, Canada already had a robust and democratic system for protecting the basic rights of Canadians – long before the UN even existed. Its origins date back to the English Parliament’s 1689 Bill of Rights, which itself drew upon rights that had developed in England over the previous millennium, and became a pillar for modern Western justice and democracy by limiting the power of the Crown, protecting speech and enumerating several critical rights common to all citizens, including the right to a fair trial. This has all been part of Canada’s legal inheritance since the conquest of British North America in 1763.

The tradition of assembling a strict legal framework around the defence of human rights grew endogenously as Canada matured. In 1944, for example – four years before the UN’s UDHR – Ontario passed its Racial Discrimination Act explicitly prohibiting “any notice, sign, symbol, emblem or other representation indicating discrimination or an intention to discriminate against any person or any class of persons for any purpose because of the race or creed of such person or class of persons.” Subsequent legislation prohibited discrimination in employment, education, rental accommodation or public spaces. Then in 1960 Prime Minister John Diefenbaker provided all Canadians with the Canadian Bill of Rights that affirms “the dignity and worth of the human person and the position of the family in a society of free men and free institutions.”

If, as Heathorn and Gouter claim, Canada was late in joining the UN’s “rights revolution”, it was because there was no need to do so.

The first “Rights Revolution”: Long before human rights tribunals came along, Canada’s legal and political system already protected fundamental rights, having inherited the English Parliament’s Bill of Rights (top left), signed by William III and Mary II (top right) in 1689, followed later by Ontario’s 1944 Racial Discrimination Act and the Canadian Bill of Rights, signed by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker (left, at bottom) in 1960. (Sources: (top right image) Classic Vision/age fotostock; (bottom photo) The Canadian Press/University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections)

The first “Rights Revolution”: Long before human rights tribunals came along, Canada’s legal and political system already protected fundamental rights, having inherited the English Parliament’s Bill of Rights (top left), signed by William III and Mary II (top right) in 1689, followed later by Ontario’s 1944 Racial Discrimination Act and the Canadian Bill of Rights, signed by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker (left, at bottom) in 1960. (Sources: (top right image) Classic Vision/age fotostock; (bottom photo) The Canadian Press/University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections)Nonetheless, a “rights revolution” did eventually arrive in Canada, coinciding with greater concern for the rights of women and recent immigrants. The first dedicated human rights commission was inaugurated in Ontario in 1962, with various other provincial and territorial bodies following. In 1977 the federal CHRC was unveiled. Each of these organizations has its own rules, but common to all is a laxity in procedure and law. The commissions act not as neutral quasi-courts but on behalf of complainants, no costs are assessed against complainants for failed claims, and onerous but essential court rules for procedures such as cross-examination are replaced with loosey-goosey tribunal hearings.

The overarching goal is to create an easy-to-navigate, quasi-legal system that’s cheaper and less intimidating than a regular courtroom. Tribunals are also empowered to make cash awards to aggrieved complainants for a wide variety of reasons, paid for by those found guilty of discriminating against them. As the B.C. Human Rights Commission website helpfully explains, “compensation for injury to dignity, feelings and self-respect” can be granted based on, among other criteria, whether the complainant has been “crying each day for the first month and [experiencing] sadness for 1 year.”

And while making the justice system easier to access and more attuned to its participants’ feelings may sound good on paper, this has been achieved – if at all – only at the cost of damaging or corrupting virtually every element of the legal process. Canada’s human rights system is, in fact, unique in the world – and not in a good way. As author Tristin Hopper points out in his recently released book, Don’t Be Canada: How One Country Did Everything Wrong All At Once, in other countries “discrimination law is enforced through the regular court system rather than via quasi-judicial tribunals that are scandalously prone to abuse.”

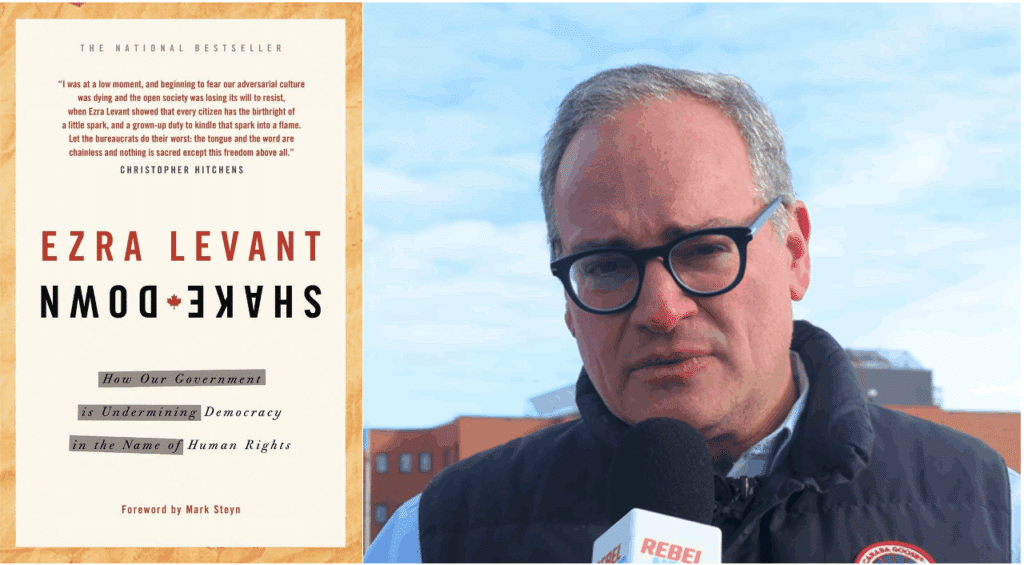

“Human rights commissions were a beautiful idea – that failed,” charges journalist Ezra Levant in his 2009 book Shakedown: How Our Government is Undermining Democracy in the Name of Human Rights. Levant comes by his cynicism honestly. Shakedown recounts his lengthy struggles with the Alberta Human Rights Commission (AHRC) over his decision as publisher of the Western Standard (a print publication no longer in operation and unrelated to the current online news site of that name) to print the infamous (but utterly legal) Mohammed cartoons. The AHRC proved preoccupied with the feelings of the Muslim complainants at seeing the cartoons displayed, showing zero regard for Levant’s free speech rights.

The complaint was eventually dismissed, but not before Levant spent $100,000 on legal fees and mounted an unusual defence strategy that included video-recording the ham-fisted proceedings and doggedly winning the battle of public opinion. Levant estimated the Alberta government spent $500,000 on the services of 15 government bureaucrats to hound him. Had he lost, of course, he could have been forced to pay off his complainants – particularly if the cartoons had made them cry or feel sad.

In his book Shakedown, journalist Ezra Levant recounts his battle with the Alberta Human Rights Commission (AHRC) to defend his right to publish the infamous Mohammed cartoons; the AHRC focussed on the feelings of the Muslim complainants, showing zero regard for Levant’s free speech rights. (Source of right screenshot: Rebel News)

In his book Shakedown, journalist Ezra Levant recounts his battle with the Alberta Human Rights Commission (AHRC) to defend his right to publish the infamous Mohammed cartoons; the AHRC focussed on the feelings of the Muslim complainants, showing zero regard for Levant’s free speech rights. (Source of right screenshot: Rebel News)Shakedown also argues that the vast public funds consumed by the human rights industry are essentially moot. The living facts of modern Canada reveal that the essential battles for equality across sex, race and religion are won. As of 2009, a Sikh had already served as premier of B.C., while the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada was a woman and a black woman was Governor-General. Unfortunately, as Levant writes, “The human rights industry spawned by Canada’s human rights commissions had become too big to fold up and throw in the recycling bin.” To keep the machinery running, new causes to champion had to be invented and “new previously unknown brands of discrimination had to be found.” The result can be seen in the current concern over the feelings of convicted bank robbers and an over-weaning desire to control how undergrads dress up at Halloween.

The article discussed an unnamed Indigenous student who’d been given special treatment by St. Mary’s administrators allowing her to drop MacKinnon’s class after the drop-out deadline. The student later recognized herself in MacKinnon’s article and complained to the NSHRC claiming she was humiliated by the anonymous reference.

None of this can occur in a vacuum. In practice, it has entailed policing the speech and other forms of expression of individual Canadians – in direct conflict with those fundamental freedoms dating back to the 1689 Bill of Rights and beyond. As Levant concludes, “An institution devoted to human rights has now become the biggest threat to our core liberties – most notably, freedom of speech.” Levant’s prescription in 2009 was to “pull the plug” on Canada’s entire human rights industry. It’s still good advice today.

An “F” for “Q”

Like Levant, John MacKinnon got an up-close and unwilling view of how human rights commissions operate today. When asked if Canada would simply be better off without them, the philosophy professor at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia immediately answers, “Yes.” As MacKinnon explains in an interview, “I would be the first to dismantle human rights commissions in Canada. I think in a just society you want citizens to have access to the law and to lawyers, but human rights commissions just aren’t the way to do that.”

Five years ago MacKinnon caught the baleful glare of the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission (NSHRC) over an article he wrote for the Society for Academic Freedom and Scholarship’s (SAFS) newsletter. Entitled “Indigenize This”, the article discussed an unnamed Indigenous student (identified as “Q”) who’d been given special treatment by St. Mary’s administrators allowing her to drop MacKinnon’s class after the drop-out deadline. Instead of getting an F, as she deserved, she was awarded a W, for withdrawn. The student later recognized herself in MacKinnon’s article and complained to the NSHRC claiming she was humiliated by the anonymous reference. The commission endorsed her claim and referred the case for adjudication, with the university and SAFS as the named defendants, which dragged on for several years.

Last year, MacKinnon and St. Mary’s sought a judicial review of the proceedings on the basis that there’d been no actual discrimination against the student (who by then had been identified as Kendra Gould). As the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, which assisted the defendants in their case, explained in a press release, “Human rights laws do not exist to prevent hurt feelings, humiliation, or offensiveness.” Instead, discrimination laws are intended only for “the most extreme type of expression that has the potential to incite or inspire discriminatory treatment.” [Emphasis added]

Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Denise Boudreau agreed and in April dismissed the case, indicating that referrals to real courts can deliver an important check on the quasi-legal human rights system. Yet the NSHRC refused to accept Boudreau’s decision and launched an appeal. SAFS’ and MacKinnon’s already years-long ordeal looked set to continue. But just this week, the NSHRC abruptly dropped its appeal. The upshot: another grotesque waste of time and resources at the hands of Canada’s human rights apparatus.

Having seen first-hand how a human rights commission was willing to sacrifice the basic right to free speech and free thought in order to protect the fragile victimhood of student Q, MacKinnon is dubious that this system can be reformed. “There are good arguments for ensuring average, normal, everyday Canadians have access to the legal system,” he says. “But establishing a parallel system of justice is a dodgy thing. And it opens up these commissions to considerable abuse.”

That’s why MacKinnon welcomes talk of abolishing the NSHRC and its country-wide counterparts: “I think they have become dangerous things.” The contrast between the emotional nature of the NSHRC claim and the precise ruling of an actual court of law was not lost on him. Justice Boudreau, he notes, “was pretty dismissive of the idea that you can haul people into court or before a human rights commission simply because you were offended about something.”

He worries, however, that even this fallback and safety valve are fragile. “Given the state of law schools these days, you could easily get a very different kind of judge,” MacKinnon says. “It’s only a matter of time before you end up with some hard-bitten ideologue who will disregard the law” and simply rubber-stamp whatever a human rights commission or tribunal has decided. Consider it one more reason to eliminate them as soon as possible.

Why is the human rights tribunal process a threat to fundamental freedoms like free speech in Canada?

How to Abolish Human Rights Commissions

While there’s renewed appetite across North America for reducing the size of government – from U.S. President Donald Trump’s chainsaw approach under the Department Of Government Efficiency to Prime Minister Mark Carney’s veiled suggestions of future budget cuts – there remains the practical issue of how to go about eliminating human rights commissions.

Critically, there’s no constitutional requirement for human rights commissions, points out lawyer Marty Moore of the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms. “Legislatures created them and so they are entirely creatures of statute,” says Moore in an interview. “They only exist because the taxpayers’ representatives – the elected MLAs and MPs and MPPs in the provincial and federal governments – have chosen to expend massive amounts of taxpayer dollars to create a quasi-judicial place to adjudicate disputes between many private individuals and entities about issues related to human rights.” Accordingly, passing one simple bill in each province and territory and one in Ottawa could remove all of Canada’s human rights commissions for good. That’s provided public opinion could be managed in that direction – a gigantic if.

Moore’s eagerness to see that happen comes from his own long and frustrating experiences with the institutions. Case in point is the apparently never-ending saga of Jessica Yaniv (aka Jessica Simpson, aka Jonathan Yaniv), a transgender woman who has repeatedly used human rights commissions to force ordinary citizens into uncomfortable and demeaning situations. In 2018, for example, Yaniv claimed it was her human right to coerce unwilling female estheticians into shaving her – still highly present – testicles. After bringing a complaint against more than a dozen beauty salons in Vancouver, Yaniv eventually lost.

More recently, Yaniv horrified parents when he attempted to participate in a beauty show for teens and young women. Here too he was unsuccessful, though not without causing severe disruption and distress. “The process in many of these circumstances is the punishment,” Moore notes. “It is an incredibly fearful, intimidating process, especially for people that don’t engage in litigation regularly. Yes, we won, but we won with expert evidence and cross-examining, and through an incredibly litigious and aggressive process.”

Moore calls Yaniv’s complaint over his Brazilian waxing “an example of a matter that, quite frankly, should have never been taken up by a human rights commission or tribunal. But because we have this expansive version of protections in the code for undefined protected grounds such as gender identity and gender expression, this is what we get.” It need not be this way.

As Moore points out, most human rights law in Canada is already covered by other statutes and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, including protections against discrimination by government or private businesses on the basis of an individual’s race, religion, sex and other key characteristics. From this perspective, human rights commissions and tribunals are merely duplicating what the legitimate justice system is already doing. Their main purpose now, therefore, is to offer vexatious, unbalanced or easily-offended individuals a way to practise low-cost lawfare against honest, law-abiding folk.

Yet despite losing his job, having to leave his home, enduring relentless smears by his enemies and being cast adrift by his erstwhile employer, May remains reluctant to abandon human rights commissions entirely.

While he agrees with Moore on the need to dismantle the human rights apparatus, MacKinnon’s sense of fairness has him arguing that the existing justice system be enhanced to ensure no one is left behind. Putting an end to human rights commissions “would entail increasing use of the legal system,” he notes. Accordingly, “I’d want to see expanding accessibility to legal services” so that all legitimate cases of discrimination are properly heard and settled.

If Canada’s human rights tribunal system were abolished, what is the proposed alternative for handling discrimination cases?

Or Might the Beast Be Tamed?

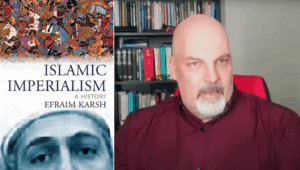

Such is the power of the concept of human rights that even individuals who have felt the full force of the industry’s wrath may still argue to preserve some aspects of it. In 2022, Collin May was fired as Chief of the AHRC following a political smear campaign against him by the provincial NDP, activists and left-wing bloggers who claimed he was an Islamophobe and thus unsuitable for the position. The sole basis for this claim was a book review May wrote for C2C Journal 13 years earlier. To its immense and enduring discredit, Alberta’s UCP government quickly buckled under the pressure.

While May’s case bears some superficial similarities with that of Dattani, May wrote the (fair-minded) book review under his own name from a standpoint of expertise and scholarly training, and was eminently qualified for the AHRC position. He held a law degree, a Master’s in Theological Studies from Harvard and another post-graduate degree from the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. As well, he had served as an AHRC commissioner for three years before his appointment as Chief.

Collin May was fired as Chief of the Albert Human Rights Commission over a scholarly review of Efraim Karsh’s historic book Islamic Imperialism; a champion of free speech and fierce opponent of cancel culture, May nonetheless remains optimistic that human rights commissions can serve a purpose if they “refocus on human rights…rather than on identity politics.” (Source of right screenshot: YouTube/Leaders on the Frontier)

Collin May was fired as Chief of the Albert Human Rights Commission over a scholarly review of Efraim Karsh’s historic book Islamic Imperialism; a champion of free speech and fierce opponent of cancel culture, May nonetheless remains optimistic that human rights commissions can serve a purpose if they “refocus on human rights…rather than on identity politics.” (Source of right screenshot: YouTube/Leaders on the Frontier)Yet despite losing his job, having to leave his home, enduring relentless smears by his enemies and being cast adrift by his erstwhile employer, May remains reluctant to abandon human rights commissions entirely. “They need a lot of changes,” May says in an interview. In particular, they “need to refocus on human rights more as protection for the individual rather than on identity politics.” In addition, “they also need to be streamlined. It’s [sometimes] taking five years to get a decision.” Recall that human rights commissions were long promoted as a quicker alternative to the court system.

May also echoes Moore and MacKinnon in identifying the problematic overlap between human rights commissions and Canada’s real court system. “About 85 percent of the complaints to the Alberta Human Rights Commission in 2021 and 2022 were derived from disputes at work,” he says. “But employment disputes now have so many venues, including the Alberta Labour Relations Board and Employment Standards Code, for employees to make complaints if they think they’ve been treated unfairly. I believe we should take a lot of those employment-based cases away from the human rights commissions entirely.”

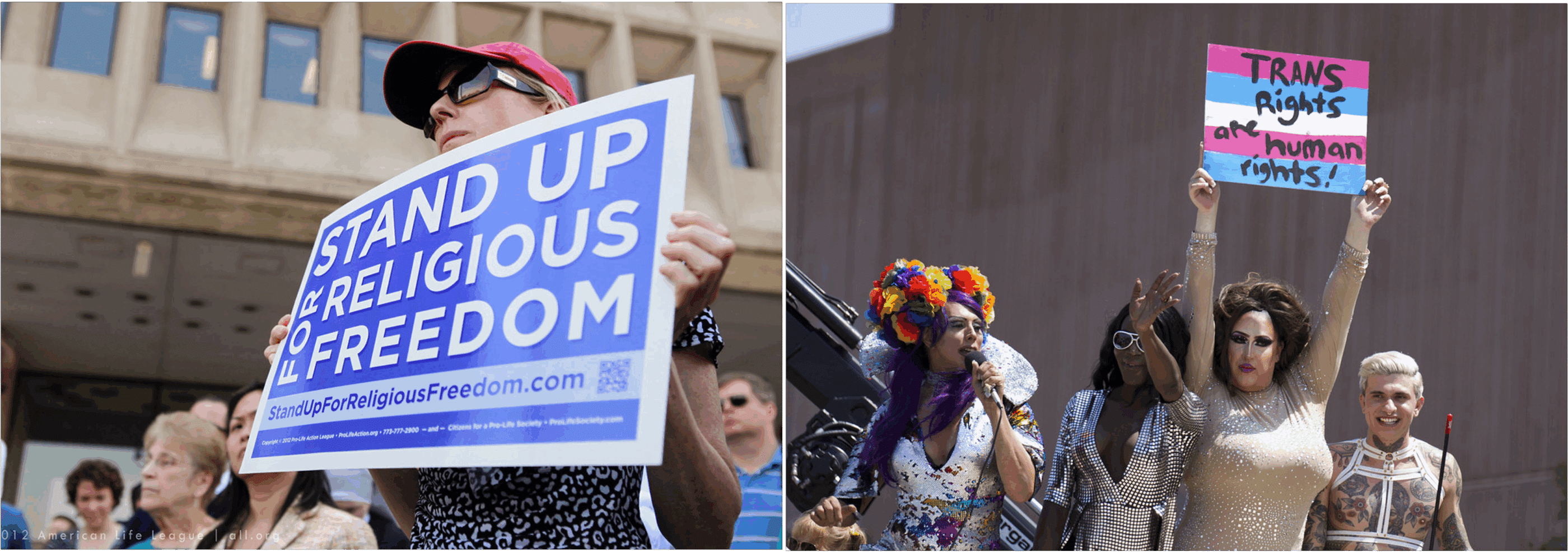

Such reforms, suggests May, who has spent much of the past several years giving presentations and writing about how to endure and oppose cancel culture, including in C2C Journal, would allow human rights commissions to be refocused on the protection of the four fundamental freedoms outlined in the Charter. These are freedom of: conscience and religion; of thought, belief, opinion and expression; of peaceful assembly; and of association. This is especially germane considering that the last two items are properly considered political rights that protect individuals from the overwhelming power of government. The human rights system has, unfortunately, largely degenerated into a way for a powerful government institution to impose its will on hapless and defenceless individuals or small business owners.

Human rights or identity rights? The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ four fundamental freedoms – of conscience and religion; of thought, belief, opinion and expression; of peaceful assembly; and of association – often clash with newly concocted identity rights, with governments and adjudicators siding with those pushing the latter. (Sources of photos: (left) American Life League, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0; (right) San Diego Shooter, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Human rights or identity rights? The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ four fundamental freedoms – of conscience and religion; of thought, belief, opinion and expression; of peaceful assembly; and of association – often clash with newly concocted identity rights, with governments and adjudicators siding with those pushing the latter. (Sources of photos: (left) American Life League, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0; (right) San Diego Shooter, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)“We’ve turned the human rights system into identity rights,” May emphasizes, drawing attention to how older and fundamental rights often clash with newly discovered (or concocted) identity rights. Nor does the human rights system worry much about consistency. As discussed earlier, it is now acceptable for government organizations to attack Christianity as being inherently discriminatory. At the same time, May points to his own experience being attacked for alleged discrimination merely for posing questions about another religion, namely Islam. “This should not be the case,” May insists. “We should be able to question any religion, to take a critical lens to religion. You’d think in a liberal democracy we’d be able to do that.” Speech, it bears mentioning again, is supposed to be protected by the Charter. But not under the lopsided rule of Canada’s human rights apparatus.

The Endgame

Created to fix a problem that never existed in the first place – this country has always had a robust legal system that, as it evolved, proved eminently capable of protecting its citizens’ rights – Canada’s human rights commissions and tribunals have instead made things worse. It’s not too harsh to call them an abject failure. Rather than standing up for the timeless rights that were first formally enunciated nearly 350 years ago, these institutions have grown fixated on inventing fanciful new rights. Here we include such innovations as the right never to be offended, the right to be shielded from the truth, the right (if you happen to be black) to a stress-free experience at the airline check-in counter, and on and on.

The only viable solution to this untenable situation is the eradication of Canada’s entire human rights superstructure. This could be done quickly and painlessly through acts of Parliament and provincial legislatures. And with no damage to anyone’s true human rights; thousands of individuals and businesses, in fact, would find their own rights better protected.

Meanwhile the United Nations, the supposed font of the “rights revolution”, is hard at work concocting even more far-fetched rights, such as the newly discovered right to “a healthy environment”. And when these new rights conflict with fundamental rights as enunciated in the Charter, commissions and tribunals habitually ditch Canada’s Constitution and go with whatever is novel.

None of this is to say that human rights are not of vital importance; our democratic society is founded upon the recognition of the individual rights of every citizen, made manifest by a justice system that is able and willing to defend them. But as we have seen, this task is far too important to be left to the 14 human rights enforcement systems currently operating across Canada. These organizations have been hijacked by interest groups and ideological activists – the notorious case of Dattani being emblematic of a much wider if generally lower-key trend – and have wandered far from their original mandates.

While it may sound radical, the only viable solution to this untenable situation is the eradication of Canada’s entire human rights superstructure. Legally and technically, this could be done quickly and painlessly through acts of Parliament and provincial legislatures. And with no damage to anyone’s true human rights; thousands of individuals and businesses, in fact, would find their own rights better protected. Most complaints currently made to commissions and tribunals ought to be dismissed out of hand since they comprise tales of bruised egos from self-proclaimed victims. Other incidents should be passed on to more suitable institutions; May, for example, makes a strong point about the overabundance of employment-related cases best handled elsewhere.

As for the small remainder of claims that may turn on valid allegations of discrimination, the court system is far better-suited to handle such cases. Its higher standards for procedure and evidence help protect innocent defendants, weed out frivolous claims ahead of time, and subject any serious claims to proper test and scrutiny. And if genuine discrimination is proven, then appropriate punishment can be applied. Such a system was how human rights were defined and protected in the era before the “rights revolution” was inflicted on Canada.

Lynne Cohen is an Ottawa-based writer and non-practicing lawyer. She has authored four books, including the ghost-written autobiography The Life of Moshele Der Zinger: How Singing Saved My Life.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.