When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence. That’s when civil war happens, because you start to think the other side is so evil, and they lose their humanity.

—Charlie Kirk in conversation on a U.S. college campus, from a recent video

The news of Charlie Kirk’s assassination reached me just as I sent an email to my editor at C2C to discuss a submission regarding another subject. He’d been concerned it had “the air of someone attempting to play cricket against barbarians with rocket launchers and hand grenades.” I countered that, though it may be a hopelessly outdated instinct, I remain committed to what the conservative philosopher Michael Oakeshott called “the conversation of mankind”. Oakeshott hoped that amidst the propaganda, ideology and raw partisanship of politics, reasoned voices of conviction and civility might still prevail.

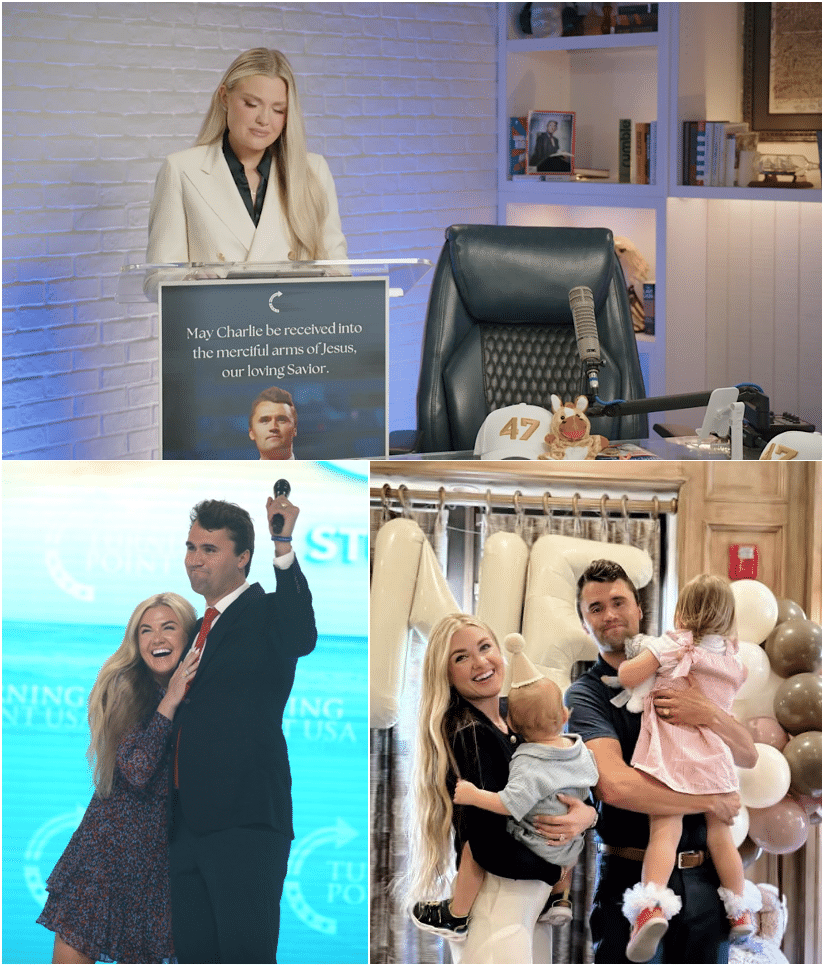

Kirk embodied this conversational approach to politics. I was not his follower nor necessarily a fan of all his political views, but his presence in American politics was inescapable. As the founder of the grassroots organization Turning Point USA, he brought hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of young people over to conservatism. He did so in an, for our time, unusual way: by touring university campuses, inviting not merely supporters but – always – critics to the microphone. In focusing on universities, Kirk strode into the lion’s den: ground zero of the culture wars (as we have described it), the fountainhead of postmodernism, critical theory and wokism.

As Johnathan Turley, professor of public interest law at George Washington University, put it, “He was particularly hated for holding a mirror to the face of higher education, exposing the hate and hypocrisy on our campuses.” So for the many young conservatives who felt intimidated or dismissed on this increasingly unsafe terrain, Kirk’s model of calm and grounded civility was empowering. His message was: don’t be afraid, stand firm and argue your point. Kirk clearly enjoyed engaging with others, taking even the most hostile questions seriously, listening sincerely and responding with a mix of good humour, confidence and reasoned argument rather than rancour. “Disagreement,” he liked to say, “is a healthy part of our systems.”

Kirk was a fan of Donald Trump, and Turning Point USA unquestionably helped get Trump re-elected last November, so Kirk was called all the predictable names: extremist, racist, anti-trans, Hitler, liar. He was routinely misquoted or had hateful opinions falsely attributed to him. He met such slurs with civility, striving to refute rather than retaliate. Habitually attacked as a “fascist”, Kirk vigorously defended Jews and Israel. He carried himself with a composure that belied his youth. His foray to the UK in May to debate at Cambridge and Oxford quickly became the stuff of legend.

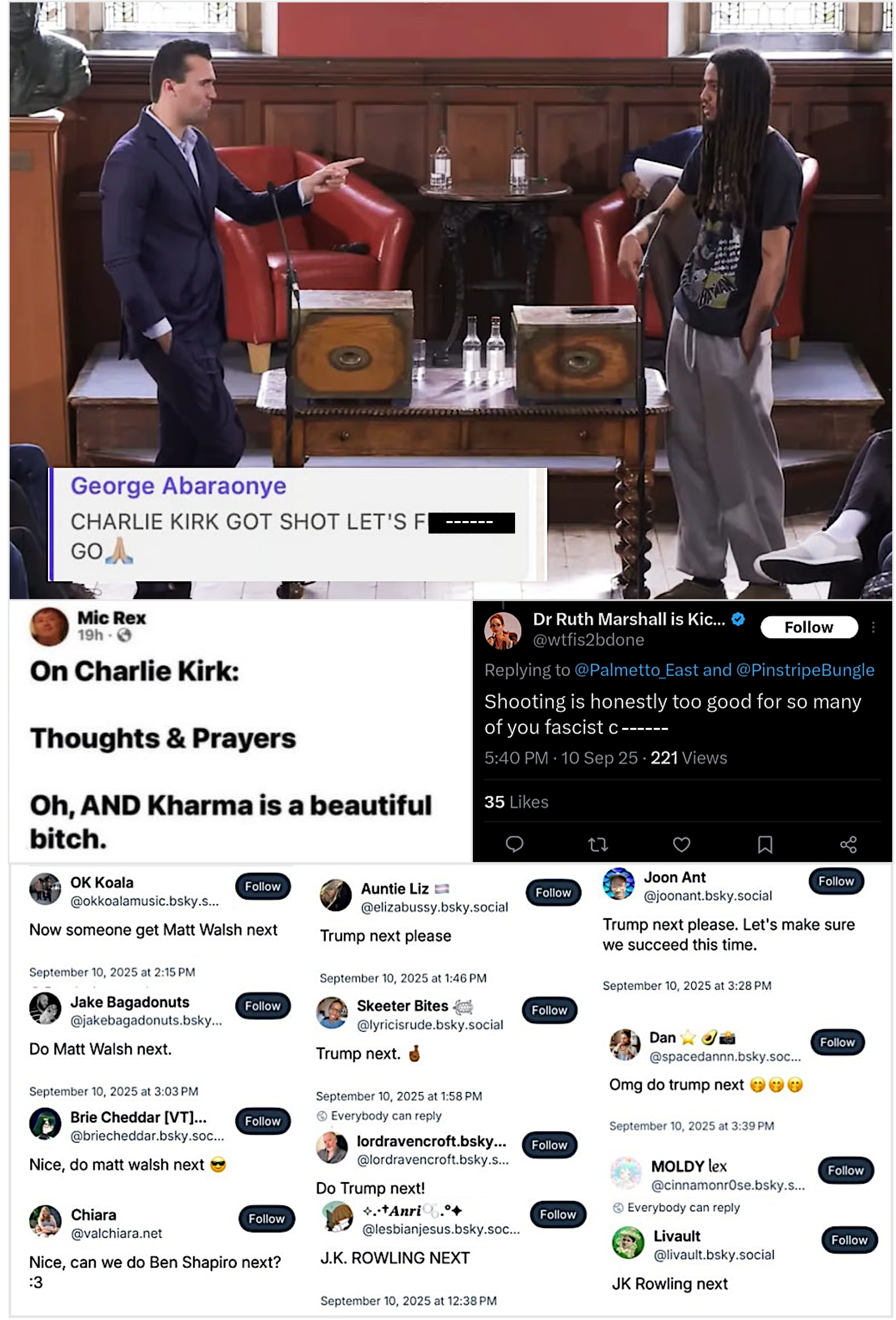

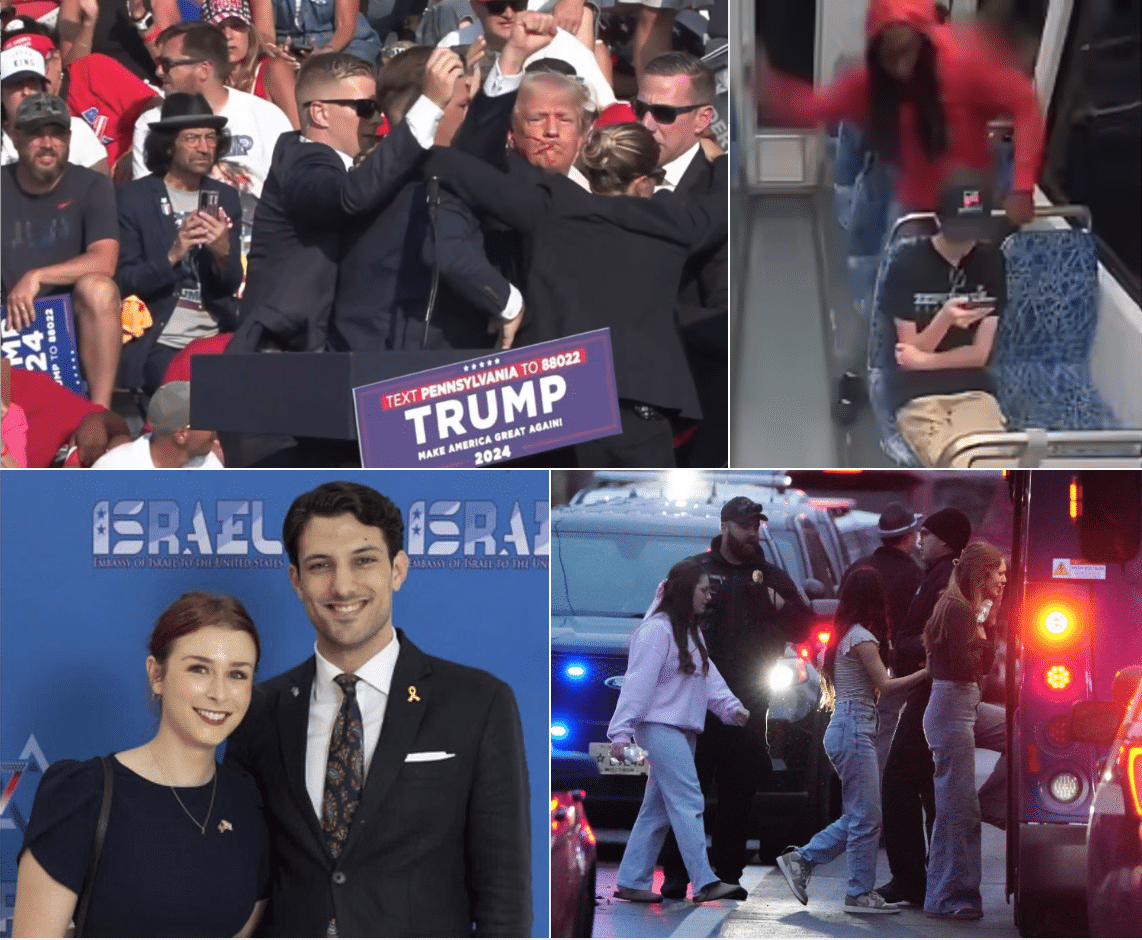

So the reaction from large swathes of the left around the world to Kirk’s death by an assassin’s bullet on September 10 at Utah Valley University in Orem, before an audience of 3,000 and beneath a banner reading “Prove Me Wrong”, has been especially chilling and ominous. News and social media as well as the political arena all swelled with callousness, self-righteous dismissiveness, gloating and even calls to arms, with some presenting the 31-year-old’s demise as a model to replicate. “He got what he deserved” and “good riddance to the fascist” were some of the milder examples. Some openly called for more killings, including of J.K. Rowling, Ben Shapiro, Elon Musk and Donald Trump. A conservative group began tracking such utterances and, within four days, had a list of more than 50,000.

A motion for a minute of silence in Congress to honour Kirk was booed by some Democratic members. Only a day earlier, Democratic Senator Chris Murphy had thundered that, “We’re in a war to save this country,” adding, “you have to be willing to do whatever is necessary” to win. Employees at a Michigan Office Depot refused to print posters announcing a prayer vigil for Kirk. A serving agent of the U.S. Secret Service was caught posting that Kirk taking a bullet to the neck, bleeding out on stage and leaving behind a wife and two young children, was “karma”. And George Abaraonye – the Oxford Union President-elect and who supports the violent destruction of Western institutions – in multiple posts celebrated the murder of the man he had not only debated but whom he had met with first and shared drinks with afterwards, including one reading, “Charlie Kirk got shot, let’s f—— go.”

I have often been perplexed why it is that those who most loudly proclaim their devotion to abstract virtues like love, tolerance, diversity, inclusivity, social justice and anti-fascism habitually justify cruelty and violence in the name of their ideals. It is as if the louder one speaks of one’s love of humanity, the easier it becomes to ignore and even reject – sometimes gleefully – simple human decency. As Sasha Stone wrote on her Substack, “The Left has been hijacked by the modern equivalent of the Manson Family.”

Enlightenment rationalism imagined the world as scientifically knowable and thus, in theory, perfectible; Marxism reinterpreted conflict as class struggle destined to culminate in utopia; the managerial state promised that expertise, data and regulation would eliminate disorder. But when we forget life’s finitude, suffering and intrinsic, immutable flaws, politics ceases to be the art of prudence and compromise, becoming a fever dream of utopia.

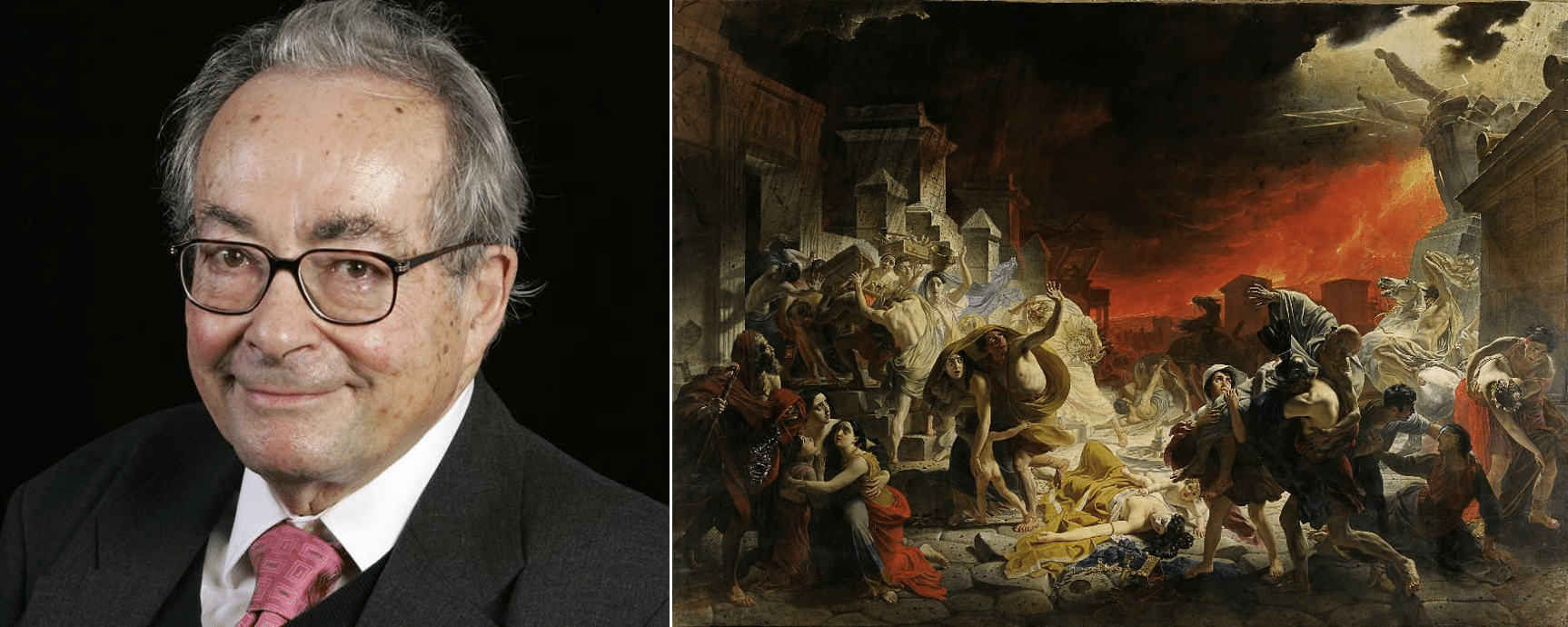

How did it become practically a mark of virtue to cheer for the death of a fellow human being? Part of the explanation, I believe, lies in what the literary critic George Steiner called the death of the tragic vision of human existence. In The Death of Tragedy (1961), Steiner argued that tragedy, once the supreme expression of human grandeur amid inevitable suffering, had perished in Western culture. Its loss, he insisted, was not merely aesthetic but civilizational.

The tragic view holds that suffering is not accidental but essential to the human condition. Fate, chance and defect cannot be mastered or abolished by will, only endured with dignity. Chance, flaw and necessity are woven into the fabric of existence. This recognition sets the tragic sensibility apart from utopian political schemes of collective redemption. Enlightenment rationalism imagined the world as scientifically knowable and thus, in theory, perfectible; Marxism reinterpreted conflict as class struggle destined to culminate in utopia; the managerial state promised that expertise, data and regulation would eliminate disorder.

But when we forget life’s finitude, suffering and intrinsic, immutable flaws, politics ceases to be the art of prudence and compromise, becoming a fever dream of utopia. And once utopia is the goal, violence is reimagined as purification, cruelty as the ticket to redemption. History offers grim reminders. The French Revolution’s Reign of Terror claimed untold lives in the name of liberty. Stalin’s gulags promised the dawn of equality. Mao’s Cultural Revolution and Pol Pot’s killing fields styled themselves as pathways to purity. Each horror arose from the refusal to accept what late 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant so memorably expressed: “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever built.”

The tragic sensibility is not equivalent to fatalism, let alone nihilism; it does not regard human life and history as accumulations of catastrophes. The tragic vision does recognize limits and, thus, tempers ambition with humility. It teaches that our motives are mixed, our victories partial, our knowledge flawed, and that human beings are capable of nobility and depravity, generosity and cruelty, great insight and blinding ignorance. To acknowledge this crookedness is not despair but clarity. Only those who accept the tragic limits of the human condition can hope to build anything that lasts.

“Tragedy speaks of the dignity of man as he is, not of man as he might wish to be,” Steiner wrote. Kirk himself frequently urged against seeking utopianism and for recognizing limits. Losing this perspective means forgetting our limits and opening the door to the cruelties of those who believe themselves pure. Politics thus becomes a substitute religion. It ceases to seek compromise and instead promises salvation through power. Opponents turn into enemies, compromise becomes betrayal, disagreement breeds enmity, and violence follows. Those who see themselves as righteous feel justified in demonizing and destroying.

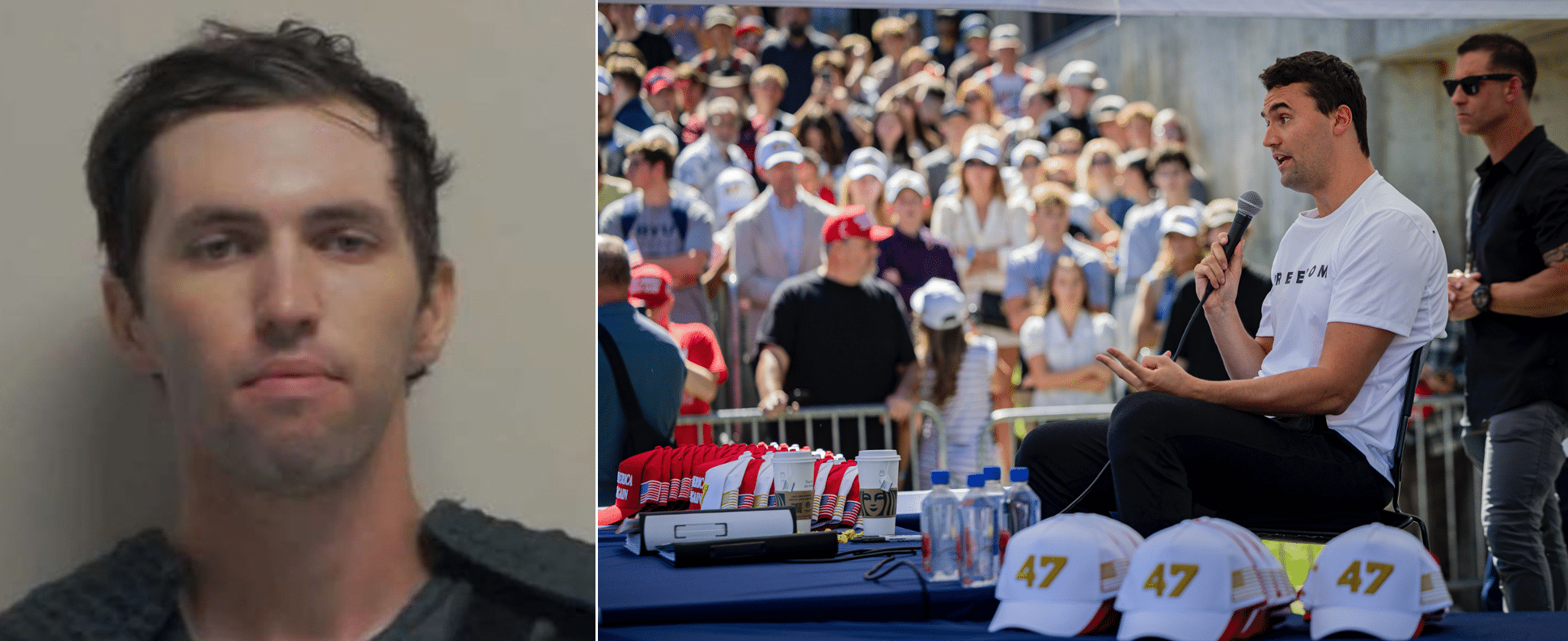

This impulse is not confined to the left, though its current expression there is particularly striking given its rhetoric of compassion. What is cloaked in the language of virtue is often little more than the intoxication of self-righteousness. And self-righteousness untempered by humility is lethal. This danger is not abstract but immediate, made chillingly clear in the figure of Charlie Kirk’s accused assassin, 22-year-old Tyler James Robinson.

Although some media sources initially attempted to portray Robinson as “right-wing” or “MAGA” – at least one outlet even claimed Robinson attacked Kirk for not being right-wing enough – a large body of facts was quickly accumulated. Robinson was raised in a stable, middle-class, politically conservative family with two parents married for more than 25 years, who were actively engaged in their three sons’ lives. In recent years, however, Robinson drifted noticeably leftward. He enrolled on scholarship in Utah State University, reportedly earning a 4.0 grade-point average, but soon dropped out.

His outright radicalization was, apparently, quite recent, and seems to have been driven or at least influenced by his roommate and lover, Lance Twiggs, who recently began transitioning to a female self-identity. Robinson recently described himself as a leftist and expressed his hatred for Trump. The shell casings on the murder weapon – an ordinary bolt-action rifle – were minutely engraved with symbols, abbreviations and sayings indicating hard-left, anti-conservative and/or pro-trans sentiments. None of the aforementioned facts are social media speculation; all were provided in public briefings by Utah’s Governor, Spencer Cox or other public officials. On Tuesday, Robinson was arraigned and formally charged with aggravated murder, a capital offence in Utah.

One can imagine Robinson, cloaked in the illusion of righteousness, seeing himself as a moral agent striking a blow against evil. In such a mindset, the opponent is no longer a fellow mortal – flawed, finite and vulnerable – but a cipher, a symbol of oppression, a barrier to redemption. The act of murder is seen not as malice but as necessity, the price of purity. Ideology masquerading as virtue – what Steiner warned would emerge when societies deny the tragic condition of mankind. Thus the logic of the post-tragic mind: the refusal to recognize in one’s adversary crooked timber like oneself. On the urging of his family, Robinson turned himself in to the authorities, who say his roommate/lover has been cooperating with the investigation.

It is noteworthy that Canadians have matched Kirk’s worst American enemies in ghoulish hatefulness and vitriol. ‘Shooting is honestly too good for so many of you fascist c----,’ posted Ruth Marshall, an associate professor of religion and politics at the University of Toronto, just hours after Kirk’s slaying.

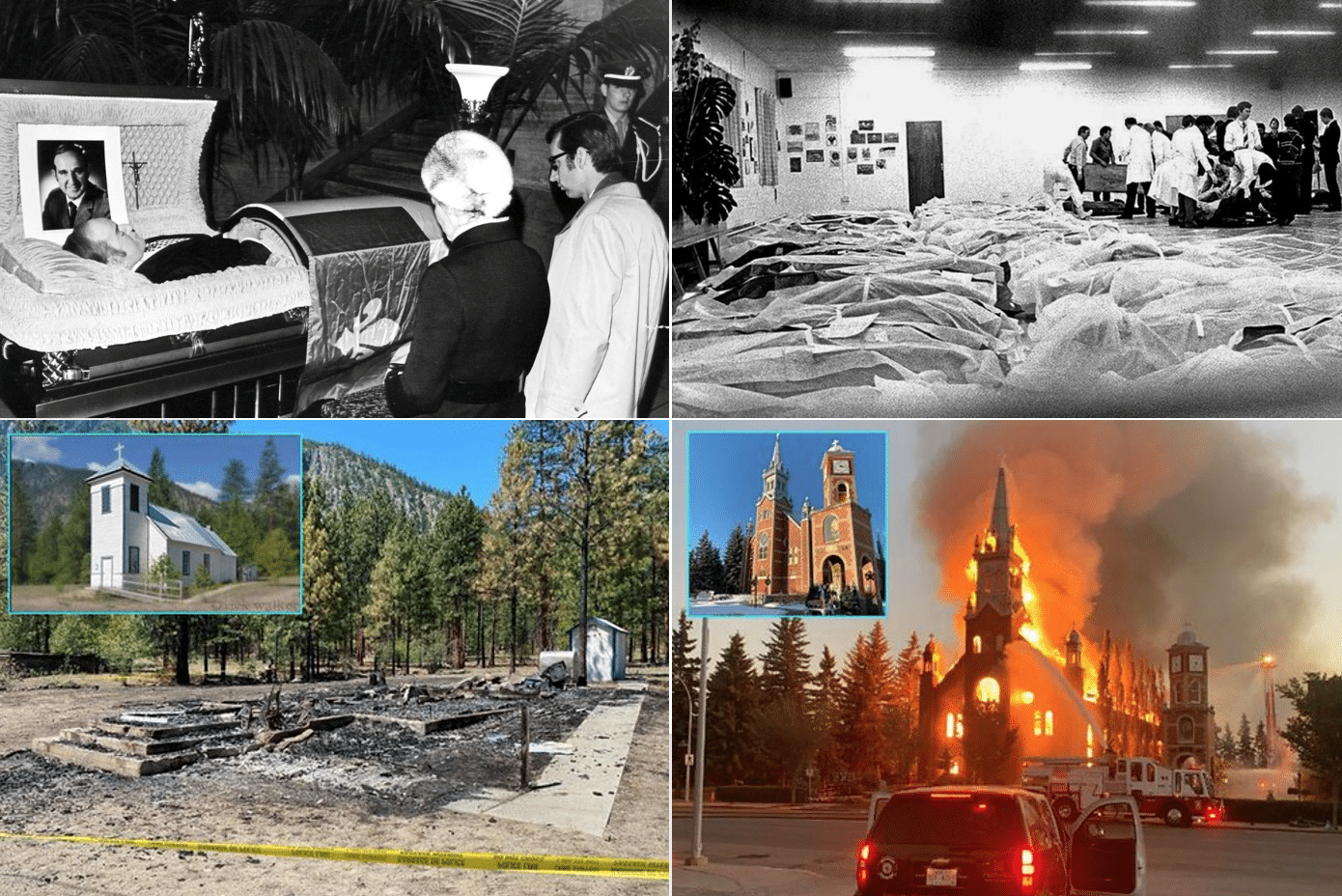

Canadians often imagine themselves immune to such eruptions. We flatter ourselves as a kinder, gentler people, protected by compromise, multiculturalism and tolerance. Yet our history tells another story. The October Crisis of 1970 saw a cabinet minister murdered in the name of Quebec independence. The Air India bombing of 1985 was instigated in Canada and killed 329 people, most of them Canadians. In 2021, following the unproven claims of unmarked graves at former Indian Residential Schools, more than 70 churches – Catholic, Anglican and others – were vandalized or burned across the country. For the past two years, nearly continuous protests have signalled a desire to demonize and even kill Jews.

Violence dressed as righteousness, then, is not alien to the Canadian soul. Such episodes show that our self-declared creed of multiculturalism, politeness and tolerance is no vaccine against extremism. Indeed, Canadian self-satisfaction may itself be a dangerous ideology, one that blinds us to alienation, dislocation and the erosion of shared meaning. We “celebrate” “diversity” as the left defines these terms, but neglect the moral and civic formation that makes genuine diversity, including of belief and opinion, sustainable.

It is noteworthy that Canadians have matched Kirk’s worst American enemies in ghoulish hatefulness and vitriol. “Shooting is honestly too good for so many of you fascist c—-,” posted Ruth Marshall, an associate professor of religion and politics at the University of Toronto, just hours after Kirk’s slaying. (Marshall had previously referred to mainstream conservative Canadian media outlets as “fascist”.) An acquaintance of mine tells of how her granddaughter’s school classmates erupted in cheers and applause upon learning of Kirk’s death, while the teacher watched impassively. A Toronto teacher went one better, showing a roomful of elementary kids the graphic assassination video and reportedly declaring that Kirk “deserved” what he got.

Although terror attacks, murders and assassinations are nothing new to either country, I believe our present moment is uniquely vulnerable. Wokist ideology continues to march through Canada’s institutions, dispensing its toxic brew (though it is being broadly resisted in the U.S.). Social media amplifies outrage, rewarding fury while punishing restraint. Every disagreement becomes an “existential crisis”. Every opponent to the right is cast as Hitler. The language of “emergency”, “racism” and “genocide” saturates politics. The path from rhetorical violence to physical violence grows short. Politicians, journalists and, now, private citizens face death threats – and more. To borrow from Ernest Hemingway’s famous line about bankruptcy, the corrosion of civic peace happens gradually, then suddenly.

What is to be done? I believe the antidote is not panic or repression, let alone a resort to popular violence as some are intimating on the right (and as some on the left are already practising), but recovery of the tragic wisdom that tempers politics with humility. This requires cultural renewal. We need to cultivate the virtues that allow citizens to live with difference, making civic peace possible: prudence, courage, humility and charity. The humanities, once guardians of civilization’s fragility, must reclaim that role.

We need a civic ethos that balances rights with responsibilities, freedom with duty, diversity with shared norms. Without restraint, pluralism degenerates into tribalism. Religious faith – or at least the metaphysical imagination it nurtures – once reminded us of mystery and of limits, engendering (and in Christianity’s case, actively urging) humility. Even for the secular, the recognition that reality exceeds our grasp can serve as a check against hubris. As the Anglo-Irish philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch observed, the moral life begins in attention, in looking outward toward something beyond the self. That act is itself an antidote to ideology. The tragic sensibility makes one much less likely to exult in another’s death, instead recognizing the helplessness that, in the end, we all have in common.

We must also speak frankly about the dangers of utopian extremism. Cold War-era Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose suffering gave him every excuse to hate the other side and elevate his own to purity, put it eloquently in his magisterial The Gulag Archipelago: “[T]he line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.” Such understanding powerfully counters ideologies that would divide the world into a binary of the pure and the impure, oppressor and oppressed, enlightened and benighted. The battle is not merely political but spiritual, within each human heart – and that recognition both demands and engenders humility.

I see hope in the soul-stirring response of Erika Kirk, who, even in the wake of her husband’s assassination, insisted that civility, dialogue and courage are not relics of a vanished past but imperatives for the present. As she declared in her first public address after his death, “The movement my husband built will not die. It won’t. I refuse to let that happen.” In the 48 hours following Kirk’s death, Turning Point USA reported over 32,000 inquiries to start new campus chapters.

The worldwide outpouring of sympathy and support for Kirk (including from the Cambridge Union) has been similarly heartening. Canadians took part in this as well, with vigils in multiple cities and a powerful tribute in the House of Commons by Conservative MP Rachel Thomas, with some Liberal MPs and ministers joining the Conservative caucus in a standing ovation. And a hopeful sign that at least some on the other side understand the situation’s gravity are the widespread disciplinary actions, including firings, levied against some of the more vicious gloaters.

Charlie Kirk’s assassination exposes the left’s troubling embrace of ideological righteousness and the peril of a politics that forgets humility. His death lays bare the fragility of civil discourse and the dangers of a political imagination that refuses to acknowledge human limits.

Amidst these glimmerings, however, Kirk’s murder remains a warning. It was, after all, on a campus, the landscape where Kirk chose to engage, where he thought the campaign for the minds of young people would be won or lost, that he was killed. Was Kirk himself attempting to play cricket against barbarians? One wonders. Notwithstanding Erika Kirk’s outstanding magnanimity, numerous younger American conservatives are warning that this event will radicalize them and that dialogue is even less likely than before.

And for Canadians to think “it can’t happen here” is the surest way to guarantee it will. The erosion of civic peace stems from ideological righteousness, the loss of the tragic sense and the abandonment of humility. Winston Churchill once mocked the “bloody-minded professors” whose grand theories paved the road to ruin. His words echo in our present, as we’ve seen.

Every destructive ideology cloaks itself in virtue, granting permission to demonize opponents and demand sacrifices. And when the tragic vision is forgotten, those sacrifices are always paid in blood. Canada’s responsibility, like that of every free society, is to confront its history honestly and protect the delicate experiment of ordered liberty with the sobriety taught by tragedy. As history has demonstrated – from Athens to Paris, from Moscow to Beijing, and now in the 21st-century West – when the tragic sense is lost, the unrestrained rhetoric of virtue turns into the justification for violence.

Charlie Kirk’s assassination reminds us of these truths with terrible clarity. It exposes the left’s troubling embrace of ideological righteousness and the peril of a politics that forgets humility. His death lays bare the fragility of civil discourse and the dangers of a political imagination that refuses to acknowledge human limits. When the tragic wisdom is abandoned, utopian illusions rush in, promising paradise but delivering blood. The tragic vision counsels us to temper politics with humility, without which freedom cannot endure. Perhaps I am attempting to play cricket in a war zone, but that is who I am.

Patrick Keeney is a Canadian writer who divides his time between Kelowna, B.C. and Thailand.

Source of main image: Gage Skidmore, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.