You can’t beat A+. It is instantly recognizable as the best possible mark anyone can earn, signifying the pinnacle of hard work and subject mastery. Despite the steady erosion in educational standards at schools and universities across Canada, many students and teachers still care deeply about what A+ means, as a grading scandal at Manitoba’s Brandon University reveals.

According to a recent Winnipeg Free Press investigation, Brandon University’s campus has been roiled by allegations that Bernadette Ardelli, formerly the school’s dean of science, changed the grade of a student in an advanced science course from F to A+ over the instructor’s objections. The student, the newspaper alleges, is related to someone known to Ardelli.

A university employee who spoke anonymously told the paper’s investigative reporter Maggie Macintosh that the grade improvement “was mathematically impossible” given that the student had not attended any of the class’s mandatory labs. Even had they earned a perfect score on every other aspect, the maximum possible grade would have been B. A former classmate told Macintosh it was “shocking” to learn of the grade change since, “I assumed [the student had] dropped the class.” In fact, the assigned A+ was a higher mark than this student earned, despite regularly attending labs.

The school’s faculty association launched a grievance over the loss of academic freedom and conflict of interest the incident entailed. But while Ardelli reportedly offered an apology for overriding the instructor’s grade without consultation, the adjusted mark apparently remains in place even after the official investigation. Ardelli has even been promoted to Vice-President of Research and Graduate Studies.

While this tale can be seen as yet another depressing example of the rampant grade inflation and decline of overall standards within the Canadian education system, it also contains the seed of a more hopeful perspective. At least some students and teachers at Brandon University feel strongly enough about the integrity of their school’s letter-based grading system that they’re prepared to speak out (even if anonymously) to defend the concept.

Where once B.C. students received a mark ranging from A to F based on how well they knew their material, now they’re placed in one of four standardized assessment categories: Emerging, Developing, Proficient and Extending.

Despite what experts may claim, there is real truth in letter grades. And they deserve a strong defence.

A “Continuum of Learning”

As part of a decades-long ideological shift in Canadian schools towards “student-centred” learning methods, the manner in which students are assessed and graded is changing dramatically. Quantitative assessment techniques that involve assigning letter grades or percentage scores on report cards based on test results and other objective metrics are being replaced with softer and more qualitative approaches that rely on a teacher’s subjective observations of a student’s progress and descriptive written feedback.

This trend is most apparent in the 2023 decision by the B.C. government to abolish letter grades in primary and middle schools and assess all students from kindergarten to Grade 9 on a new Provincial Proficiency Scale. Where once B.C. students received a mark ranging from A to F based on how well they knew their material, now they’re placed in one of four standardized assessment categories: Emerging, Developing, Proficient and Extending.

This move is extremely popular within the education establishment. In an article in The Conversation, an online journal that publishes essays and commentary by academic writers, University of British Columbia education professor Victor Brar claims the new scale improves the schooling process by shifting focus away from student deficits and towards student strengths. It does this, he says, by emphasizing the “process of learning itself” rather than verifiable test results.

Brar dismisses old-school grading systems as being too hard on students. “Letter grades and percentages position some students (with As or Bs) as having strengths, while other students (with Cs or Ds) are regarded as not even being on the continuum of learning. Letter grades highlight the deficits of underperforming students, thereby perpetuating a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts,” he writes.

B.C.’s new proficiency scale, Brar admits, has left many parents worried that the lack of objective marking standards may cause their children to “lose their competitive edge” once they reach university. (Sources of photos: (top) woodleywonderworks, licensed under CC BY 2.0; (bottom) Brandon Sun)

B.C.’s new proficiency scale, Brar admits, has left many parents worried that the lack of objective marking standards may cause their children to “lose their competitive edge” once they reach university. (Sources of photos: (top) woodleywonderworks, licensed under CC BY 2.0; (bottom) Brandon Sun)Rather than sort students by those who know the material and those who don’t, Brar argues it is better to report on how students are learning. “The centrepiece of B.C.’s new curriculum is a set of core competencies – cross-curricular proficiencies for students in the domain of communication, critical thinking and social-emotional awareness and relations,” he writes. These softer skills are prioritized over measurable outcomes – like the ability to recite facts and figures or perform required math calculations.

Standing logic and common sense on their heads, Brar further argues that this new system is actually more rigorous and reliable than what it’s replacing. “Although letter grades had the appearance of being definitive, they were ambiguous: students received the very visible stamp of a letter grade or percentage but had little understanding of how that grade came to be,” he states. He thus claims an earned A or F is fuzzier and harder to understand than a teacher’s subjective opinion of how that student is doing.

Even Brar admits, however, that the recent move has left many families uneasy. Besides concerns about the new scale being unclear and subjective, there’s also the issue of how it will affect the future path of students making their way through the education system to adulthood. Parents, he has heard, “express concern around the flip-flop between how the scale is applied in kindergarten to Grade 9, but not in grades 10 to 12 or post-secondary institutions.” Some also fret their kids will “lose their competitive edge” once they reach university, as the post-secondary system (for now at least) still maintains a strict focus on test results, letter grades and competitive rankings.

What is the B.C. Provincial Proficiency Scale, and how does it differ from traditional grading schemes?

In 2023, the British Columbia government replaced traditional letter grades for students in kindergarten through Grade 9 with a four-tier scale: Emerging, Developing, Proficient and Extending. Unlike traditional grading methods that measure mastery against objective metrics, the new scale focuses on the process of learning and core competencies such as social-emotional awareness. Critically, Emerging and Developing are defined as not being a failing grade. This eliminates a traditional quantitative measure used to identify students who are falling behind.

Not to worry, the education professor declares. The new Provincial Proficiency Scale “doesn’t necessarily ignore competition. Instead, it asks students to be concerned with their competitive relationship with themselves first, before considering it with others.” In other words, it ignores competition altogether.

Confused By Design

Brar is right about one thing. A lot of parents don’t like the new system. According to a 2023 readers’ poll by the Delta Observer community newspaper conducted when the policy was first rolled out, only 8 percent of parents welcomed the new scale; 84 percent wanted a return to the old letter grades.

A year later, the Fraser Institute released a scientific poll conducted by the polling firm Leger that came to a similar result. The survey asked 1,200 Canadian parents with school-aged children their thoughts on the importance of “regular, clear student assessments”. Ninety-eight percent said clarity was very or somewhat important. A similarly massive plurality of 93 percent of parents said letter grades were “clear and easy to understand” while a majority struggled to define what “Extending” or “Emerging” actually meant. Again, a majority of B.C. parents opposed the move away from letter grades.

A closer look at the definitions for these new terms suggest parents are right to worry about their usefulness. From the provincial booklet “Unpacking the Proficiency Scale”:

- “Emerging” indicates that a student is just beginning to demonstrate learning in relation to the learning standards but is not yet doing so consistently. Emerging isn’t failing.

- “Developing” indicates that a student is demonstrating learning in relation to the learning standards with growing consistency. The student is showing initial understanding but is still in the process of developing their competency in relation to the learning standards. Developing isn’t failing.

- “Proficient” is the goal for all students. A student is Proficient when they demonstrate the expected learning in relation to the learning standards. Proficient is not synonymous with perfection.

- “Extending” is not synonymous with perfection. A student is Extending when they demonstrate learning, in relation to learning standards, with increasing depth and complexity…Extending is not the goal for all students.

Beyond the fact none of the categories entail failure or perfection in relation to the provincial curriculum, very little else is clear. They seem designed to obscure rather than illuminate a student’s progress by studiously avoiding quantifiable results or coherent conclusions.

‘Students who actually need help the most could be in a situation where they’re falling through the cracks instead of being noticed earlier,’ VanHof warns.

Most B.C. parents see this as a giant backward step, concluded Paige MacPherson, the Fraser institute’s associate director of education policy. “A clear majority of Canadian parents with children in K-12 schools find letter grading easier to understand…than the B.C. government’s new descriptive grading,” she writes in her summary of the poll report mentioned above. MacPherson urges any provincial government seduced by the idea of abandoning traditional assessment methods to be “mindful” that “these changes do not make report cards clearer and easier for parents to understand their child’s academic progress.”

An “Emerging” Crisis

The conceptual fog enveloping B.C.’s new proficiency scale is creating genuine, real-world problems, says Joanna DeJong VanHof, education program director at the Ottawa-based think tank Cardus. Despite what supporters claim, VanHof explains in an interview, qualitative assessments tend to measure student performance “relative to their peers” since the grading categories are restricted to a few large and poorly defined buckets. As a result, the traditional focus on what an individual student is actually learning is lost. This neuters the feedback mechanism that report cards are supposed to entail, which can create significant problems.

VanHof imagines a scenario in which a child is labelled as an Emerging learner for many years. Under the old system, that student would likely have earned Ds or Fs, raising red flags that would have sparked interventions at home and school. Now, she says, it may never become obvious to parents that their child is failing. Remember, the official definition of “Emerging” explicitly states that it isn’t a failing grade. The resulting confusion could mean the student doesn’t promptly – or perhaps ever – receive the remedial assistance he or she needs. “Students who actually need help the most could be in a situation where they’re falling through the cracks instead of being noticed earlier,” VanHof warns. Concrete grades, she says, “translate objective standards of learning into meaningful criteria for parents to understand.” Everyone knows this, she adds, because such standards have been around for centuries. Objective marking schemes allegedly date back to 1792, when University of Cambridge tutor William Farish repurposed a nearby shoe factory’s system for determining whether its products were “up to grade” as a way of ranking his students’ progress.

While the stated purpose of removing letter grades is to make the school system more equitable and ensure struggling students are not labelled as failures, another education expert predicts B.C.’s new system will likely have the opposite effect: the greatest costs will be borne by the least fortunate families.

John Hilton-O’Brien is executive director of the Alberta-based Parents for Choice in Education. His organization lobbies for a greater role for parents in the education system and favours traditional assessment standards. Hilton-O’Brien worries that B.C.’s new rules will end up exacerbating inequalities. “Well-resourced parents can hire tutors, they can interpret these opaque competency-based reports, and they can navigate the system,” he observes in an interview. But not all families have access to such resources, or have the spare time to figure out whether “Emerging” is better or worse than “Developing”. Disadvantaged students will thus be at the greatest risk of being left behind under B.C.’s new system.

More broadly, Hilton-O’Brien worries that the new measurement system could estrange all parents from their children’s education by turning schools into the “sole interpreter of student progress.” If parents lack a proper understanding of how their children are doing because report cards no longer contain actionable information, families will be pushed further away from the nexus of decision-making for their children. In essence, Hilton-O’Brien says, the educational bureaucrats who concocted this new system have interposed themselves between teachers and students. The new system will also make life tougher for teachers, VanHof suggests, as they must now interpret and translate the vague categories of “Emerging” and “Extending” when meeting with confused parents.

B.C.’s new proficiency scale may even increase grade inflation, a longstanding problem in Canadian schools. VanHof explains that because the proficiency scale is inherently subjective, standards can vary from class to class depending on the teacher and the mix of students. Given the vagueness of the categories, students may end up being placed in higher proficiency levels than they deserve. Hilton-O’Brien echoes this view. “What letter grades do is introduce an element of accountability to the system itself,” he says. Removing those As and Fs erases “visible records” of underperformance and makes the entire system unaccountable.

How do no-fail and de-streaming policies impact the classroom environment?

Policies such as Ontario’s 2021 de-streaming of Grade 9 and the broader no-zero approach create significant challenges for teachers by forcing them to instruct students with vastly different grade levels of ability in a single class. These initiatives are rooted in an ideological pursuit of equalization of outcomes, which assumes that any disparity in student achievement is a sign of an unjust system. The practical results of this education policy can be seen in the decline in teacher morale and the increase in classroom chaos, as educators must manage a wide diversity of student needs and abilities.

Beyond Letter Grades: De-streaming and No-Fail

The disappearance of letter grades from B.C. public schools is not an isolated policy change, Hilton-O’Brien cautions. Rather, it is part of a much larger trend affecting assessment standards across the country. In 2010, for example, Ontario created a new grading standard called Growing Success which retained letter grades but expanded the range of qualitative assessments to include teacher observations, student portfolios and self-assessments. It also introduced a “no-zero” approach that discouraged teachers from failing students or giving penalties for handing in their assignments late.

The removal of letter grades, de-streaming and no-fail guarantees all spring from the ‘same philosophical soil,’ says Hilton-O’Brien. ‘There’s been this ideological shift from excellence to equalization of outcomes. If unequal outcomes persist, then the system must be unjust.’

Then in 2021, Ontario rolled out a “de-streaming” policy that eliminated separate academic and applied courses across Grade 9. Previously, applied courses in math, for example, focused on everyday math problems while academic courses prepared students for university-level problem-solving. The purported goal of de-streaming – similar in intent to B.C.’s proficiency scale – was to ensure equal treatment of all students, regardless of ability. According to the teacher-run group Ontario Educators, the old streaming system reinforced economic disparities and racism since black and Indigenous students disproportionately enrolled in applied programs. “De-streaming is not only a good thing for students, but an ethical imperative,” its website declares. Some Ontario school boards have since extended de-streaming to Grade 10 courses on an ad hoc basis.

National problem: Similarly to B.C.’s proficiency scale, Ontario’s Growing Success assessment standard introduced a “no-zero” approach that discourages teachers from failing students or docking marks for late work.

National problem: Similarly to B.C.’s proficiency scale, Ontario’s Growing Success assessment standard introduced a “no-zero” approach that discourages teachers from failing students or docking marks for late work.As Hilton-O’Brien observes, however, removing the “evidence of unequal outcomes” does not remove inequality. Rather, de-streaming and no-fail policies simply create more problems inside the classroom. “When you de-stream, you’re putting students with potentially three or more grade levels of difference into one room,” he says. The same effect occurs when the possibility of failure is removed and students are moved up regardless of ability. Now teachers must juggle a huge variety of competing needs within a single classroom. “They’ve got to perform the emotional labour for struggling students who can’t keep up and they’ve got to defend the system to parents who are confused or frustrated,” says Hilton-O’Brien. “These policies degrade teacher morale.” There is also evidence this chaos is contributing to greater school violence as classroom conflicts turn physical.

The removal of letter grades, de-streaming and no-fail guarantees all spring from the “same philosophical soil,” observes Hilton-O’Brien. “There’s been this ideological shift from excellence to equalization of outcomes. If unequal outcomes persist, then the system must be unjust. Therefore, we should eliminate the structures that reveal differences.” Such a worldview ignores reality, he says: “People naturally differ in pace and disposition and in their aptitudes.”

Instead of enforcing equity of outcomes, he says, the system should give each student what they need to succeed. If students receive failing grades, there should be mechanisms to help them master key concepts before they’re sent onward to the next grade. Simply removing the distinctions between students does not address the gaps in their knowledge. It just punishes the students who are struggling.

What are the measurable consequences of declining educational standards in Canada?

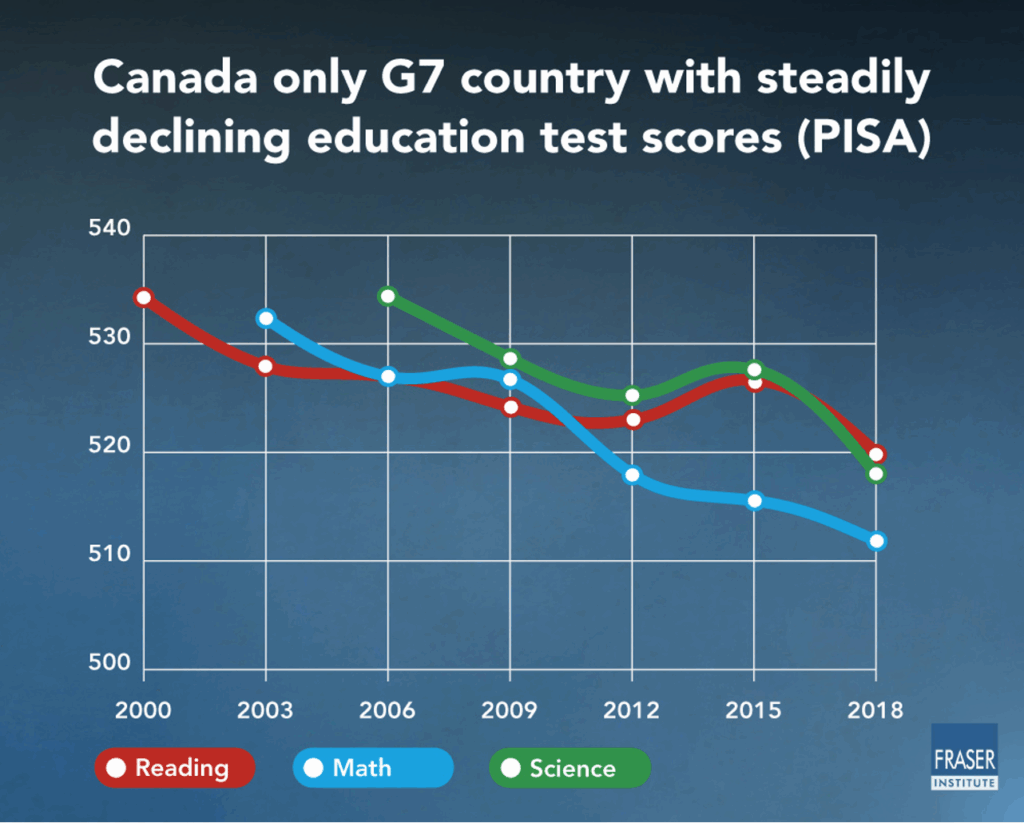

The shift toward student-centred and qualitative assessment has coincided with a measurable decline in the academic performance of Canadian 15-year-olds and a rise in grade inflation. According to international PISA tests, Canada’s results from 2003 through 2022 in math dropped by 35 points, a decline equivalent to losing two full grade levels of learning. Some provinces, including Alberta and Ontario, have implemented “back-to-basics” reforms to their provincial curriculum. However, the broader national trend suggests the move away from objective learning standards is degrading the quality of Canada’s education system relative to its international peers.

The Pushback

The accumulated evidence suggests this slackening of school standards is weakening the overall quality of Canadian education. Over the past decade, for example, Canadian students’ scores on testing under the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) have steadily trended downward. Organized by the OECD, PISA assesses the reading, math and science skills of 15-year-olds in countries around the world. Although Canada often ranks well, its scores have been consistently declining. From 2003 through 2022, Canada’s PISA results in math fell by 35 points, roughly equivalent to a drop of two whole grade levels (for those who still think in grade levels, as opposed to proficiency scales).

Some provinces are paying attention. Alberta is rolling out a multi-year recalibration of its entire school curriculum that puts much greater emphasis on fact-based schooling. Ontario has promised its own “back-to-basics” curriculum reform, set to take effect at the beginning of the next school year, that promises to include direct math instruction in kindergarten. It should be noted, however, that the Fraser Institute has criticized Ontario for failing to fully rid its school curriculum of damaging diversity, equity and inclusion criteria. The province is also acting on a major investigation into provincial reading skills that found Ontario’s previous student-centred approach to literacy instruction left many students unable to read. In response, the province is reforming how reading and writing are taught, chiefly by returning to conventional – and amply proven – “phonics”-based instruction. Positive change does appear possible.

Independent schools provide an additional safety valve for parents confused or frustrated by the ideological obsessions of the public school system. John Wynia is league coordinator of the League of Canadian Reformed School Societies, which represents 20 independent Christian schools in Ontario. Wynia himself taught at Hope Reformed Christian School in Paris, Ontario, where his expectation that students work hard and achieve good grades earned him a reputation, he recalls, as a “tough” teacher. In an interview, he says students have “often thanked” him for his demanding approach after they graduated, “because when they went to university, they were very well-prepared.” And despite Ontario’s aversion to late penalties, Wynia continued to deduct marks for late school work, although he says he granted extensions when requested.

“The reason people are going to independent schools is because they are better at communicating with parents,” notes Hilton-O’Brien. Despite the official demise of letter grades in B.C., he says many non-public schools still informally provide that information to parents who demand it. “A teacher might say in the parent-teacher interview that your child would get a B minus,” he observes. Similarly, VanHof says independent schools have done a lot of work around implementing the new policy by translating unhelpful categories such as Emerging “into terms of real objective standards of learning.” She also sees independent schools as being more “nimble and able to make changes that are in line with their mission and vision” rather than being bound by ponderous bureaucratic structures.

If the issue is how to address equity concerns and the performance of certain racial groups, Wynia points to the American No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) as a better model for government intervention. This legislation, passed in 2002 under Republican President George W. Bush, was designed to tackle what Bush famously called the “soft bigotry of low expectations”. This term refers to the self-defeating belief that some groups in America are incapable of meeting higher educational standards due to their race, background or socioeconomic status – and thus must be protected from failure by making failure impossible. This appears to be the thinking behind the new B.C. proficiency scale that similarly doesn’t include an option for failure.

The NCLB took a different approach. It measured school progress with annual standardized testing in reading and math and sought to raise standards at schools with kids who were predominantly poor and/or black. Evidence five years later showed higher student scores among many of the target populations, especially blacks. “There’s a lot of research and a lot of evidence that shows that if you have high expectations for your students, your students will rise to meet those expectations,” Wynia says.

Demand better: The No Child Left Behind Act tackled the “soft bigotry of low expectations” by tracking progress and raising expectations across all schools. Shown, U.S. president George W. Bush signs the bill in Hamilton, Ohio on January 8, 2002. (Source of photo: Paul Morse/White House)

Demand better: The No Child Left Behind Act tackled the “soft bigotry of low expectations” by tracking progress and raising expectations across all schools. Shown, U.S. president George W. Bush signs the bill in Hamilton, Ohio on January 8, 2002. (Source of photo: Paul Morse/White House)Gritty Optimism

At the broadest level, VanHof observes, “Education is about the formation of persons.” Beyond day-to-day individual learning and skills retention, this includes longer-term goals such as building resilience, capacity and lifelong learning skills that can help a student succeed throughout their life. Hiding failure or attempting to create the illusion that all students are equal in their abilities and outcomes undermines this larger educational process aimed at the whole person. Students are, in essence, being told lies about their capabilities and future prospects.

Eckert warns against an excessive focus on the well-being of students – as is the focus of most educators today – because it exempts students from any sense of struggle.

VanHof points to the work of Jonathan Eckert as offering a better way. Eckert is a professor of Educational Leadership at Baylor University in Texas and a former consultant to the U.S. Department of Education under both the Bush and Obama administrations; he is also a Senior Fellow at Cardus. Eckert coined the phrase “gritty optimism” to reflect his findings that teachers need to challenge students and base their efforts on a realistic view of the world.

“Gritty optimism is the belief that students can become more of who they are created to be,” Eckert writes in a December 2025 article in the academic journal Improving Schools. “Learning is productive struggle,” he observes, and educators who foster this in their students tend to “base their optimism on evidence and experience.” Eckert also warns against an excessive focus on the well-being of students – as is the focus of most educators today – because it exempts students from any sense of struggle. While well-being may seem like a worthy goal, without sufficient challenge and hardship, he says, students come to think “everything is happy, comfortable, and easy.” That may sound like a nice vacation, but Eckert is convinced it’s no way to run a school, or build an adult.

VanHof agrees. “Gritty optimism really captures the fact that education done well is education in which there’s hard work involved,” she says. Abolishing letter grades, making all progress relative, eliminating the possibility of failure and disenfranchising parents from the entire educational process is the exact opposite of gritty optimism. It’s what you might call a solid F.

Christina Park is a graduate student in the Master of Journalism program at the University of British Columbia.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.