When lawyers recently launched a sexual harassment lawsuit against the RCMP, and which now numbers 300 female RCMP officers as claimants, it was, and is, illuminating to peruse the opinion pages. There, one can find a daily dose of indignation levied at the police force for its failure to keep pace with social progress and purge itself of institutionalized sexism.

Sexual harassment is supposed to reference clear, morally deplorable behaviour related to sex (lascivious actions or comments towards anyone regardless of gender). However, not all cases of sexual harassment fall within clear boundaries of “morally deplorable” behaviour, nor does everyone agree as to where those boundaries fall. As such, the interpretation of sexual harassment has ballooned and blurred the lines of guilt and innocence.

The basic guideline for determining sexual harassment stems from then Supreme Court Chief Justice Brian Dickson’s definition in 1989 of sexual harassment as “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that detrimentally affects the work environment or leads to adverse job-related consequences for the victims.”

“Unwelcome” is the operative word. Unlike in a murder trial, adjudicators in a sexual harassment case usually do not try to determine if a crime has been committed, but whether certain behaviour amounts to a crime. Verdicts ultimately come down to a judge’s, or a panel’s, interpretation of evidence, not just the evidence itself. And the evidence that bears the most weight is whether the victim deems the alleged behaviour as “unwelcome.”

“Social progress” versus nuance

Society’s going tally of unwelcome behaviour grows daily. Every time we identify another “no-no” (a teacher who puts her hand on a student’s shoulder, a boss who compliments a female subordinate on her outfit, a co-worker who repeats a joke within earshot of another colleague who takes offense), too many assure us another step has been gained in the ladder of social progress.

The irony of such progress over the past few decades is that it occurs within ever- tighter boundaries of political correctness. We claim to have reached an unprecedented level of openness in society, yet we talk, act, and think within surprisingly and increasingly narrow bounds. The risk of offending someone is simply too great. And when we do allow ourselves to speak in a politically incorrect manner – what was once called “freedom of expression” – someone will invariably get offended, even if on behalf of someone else.

Matters related to sex especially demonstrate the contradiction between modern “anything goes” social norms and the constraints of political correctness.

On the one hand, some cover their shocked mouths at Barack Obama’s comment that Kamala Harris is the “best looking attorney general” in history, a comment which, in a different time and context, might be taken as a lighthearted compliment but was instead deemed “objectification.” Alternatively, many are okay with formerly (and often still) controversial acts like premarital sex and abortion. Then consider our pop culture, in which the most risqué music videos fare best and sado-masochism is the new flavour for young adult novels.

The condemnation reflex

We live in an increasingly sexualized society, yet are conditioned to stay neatly within socially acceptable boundaries—and to gasp indignantly at anything that falls outside of them. The result is that ever-fewer people think through issues rationally, much less talk about them in a robust and challenging way. Too many only have time for reaction, and in matters related to sexual harassment, it increasingly seems there is only one “correct” reaction—and it must come quick.

Sexual harassment of the “morally deplorable” variety does exist, even if no one files a lawsuit. Frequently, and unfortunately, victims keep mum about incidents for any number of reasons, from fear to social pressure to misplaced notions of shame. The mistreatment of colleagues or subordinates deserves retribution, not only for the sake of justice but for the sake of enabling all of us to go about our daily lives free from molestation.

Yet the downside of our current reliance on a term as subjective as “unwelcome” to define sexual harassment is how it prevents people from being free from unexpected allegations, dependent on context and someone else’s feelings. (If our sexual harassment codes applied in Paris, half of French men—and perhaps a few women – would end up charged.) It is impossible for Canadians to know in every instance what might constitute “unwelcome” behaviour to everyone they encounter. A comment from one person might be found funny by a friend, yet that friend might find the same comment from someone else offensive. Even if the intention, probably to draw a laugh, from both utterers was the same, the joke may only be perceived as “welcome” from one.

In this world, it is not harassment that we prosecute, but, at least in some instances, unpopularity, social awkwardness, and personal animosities. The intention of the utterer is rarely considered in harassment cases. Much more weight is given to perception of the hearer – if the victim says they felt uncomfortable, or if they feel their work environment was adversely affected. The courts thus often rule in favour of protecting the victim’s right to freedom from offense, even if in doing so, they ultimately rule against the unwitting perpetrator’s right to freedom of expression.

Sexual harassment is thus a remarkably slippery issue on which to adjudicate and a remarkably powerful instrument for anyone who dares to wield it. If the requisite basis for a legal case is nothing more than an individual’s “word,” how they felt negatively affected by a comment, then the door is left wide open for those who might fabricate such sentiments out of a base desire to ruin a boss’s career or bolster a bank account.

While one is inclined to believe in the existence of a social moral compass that diverts individuals from acting on such impulses, the realist recognizes it often fails, or is absent in some people. False accusations do occur. When the flexibility of sexual harassment arbitration is exploited for unethical gain, the entire concept of “sexual harassment” as an offense is diluted; this is to the detriment of those who rely on its legitimacy when seeking compensation for real injuries.

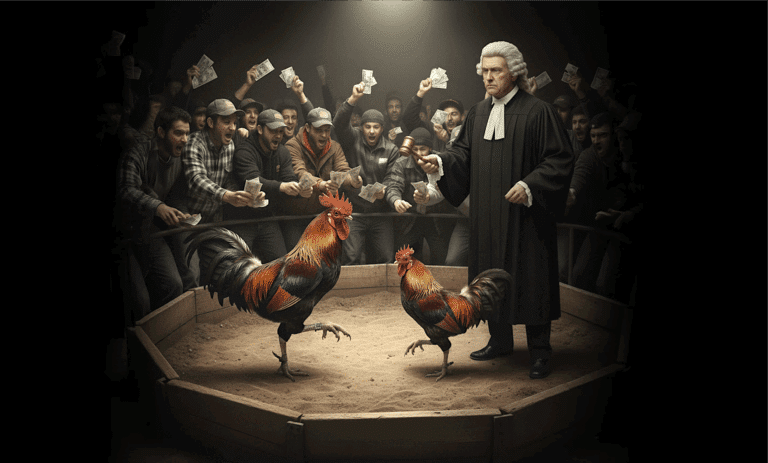

This is the danger of a class action lawsuit. Three hundred plaintiff submissions are bound to run the full gamut of perceptions, some correctly identifying intended harassment and others wide of the mark, yet the verdict will apply to all. The trial has yet to begin but wager the court will offer a harsh judgment to the RCMP. Then, when the gavel finally falls, listen for the whoops and shouts from the plaintiff’s support benches and the awkward silence from those who might have questioned the decision. After all, who can argue with social progress?

~

Yule Schmidt is a Special Assistant to the Yukon cabinet. She holds a B.A. in History from Stanford University and an M.A. in History from McGill University. This article reflects her personal views and not that of her employer.