No medal is sufficient to honour the veterans of the Bomber Command

Canada’s recognition of Second World War Bomber Command veterans last month was long overdue. The delay is attributed to the controversial nature of the raids – their objective was to destroy the German war machine and break morale, and many civilians died in the process. The effectiveness, and morality, of the raids has thus been questioned. For decades, the Canadian government avoided the controversy by ignoring the veterans, reinforcing the notion that they had committed wrongs. This notion was reinforced by the Canadian War Museum’s apologetic exhibit of the Bomber Command five years ago. The storyline remains that “our boys” committed a wartime atrocity which is a black mark on our nation’s history.

I have a degree in military history. I have studied wars and their politics, strategies, and atrocities. But I will be the first to admit that I know nothing about war. I do not know what it feels like to fire a gun at someone, and have one fired at me. I do not know what a friend’s body looks like after a grenade has struck him. And I do not know what alchemy allows soldiers to run into the fight with purpose rather than away from it with fear.

War is incomprehensible unless you have fought in one. The smells, the sounds, the fear, and the disgust of a battlefield cannot be conveyed by film or prose, only experience. For millennia, war and civilian society were kept separate to shield civilians from seeing the horrors of battle and because they would not be able to understand what they see.

Yet this division between civilian society and the military has evaporated over the past century. It started with the World Wars, particularly the second. Soldiers no longer left for distant battles as they did in the past; battles came right to their towns. Civilians were no longer shielded, at least in Europe. In North America, they were luckily protected by two oceans so most Americans and Canadians never saw the atrocities of battle first hand. And for the most part, the Second World War is still remembered as “the Good War” with a few exceptions – Dresden, Tokyo, and Hiroshima. By and large, soldiers left for the war and returned to crowds cheering their victories and mourning their losses.

Vietnam changed the way civilians view war. For the first time, people saw an uncensored version of what soldiers do on a battlefield. Graphic images were projected daily onto the T.V. screens in every American living room. It was nothing new – American soldiers in La Drang were no less noble than their counterparts in Iwo Jima. Yet the public had not watched Iwo Jima unfold. They did not see American G.I.’s clearing caves by throwing in grenades without checking for women and children, nor did they see Japanese soldiers feigning surrender before pulling pins from concealed grenades, blowing up themselves and their captors. But the public saw My Lai.

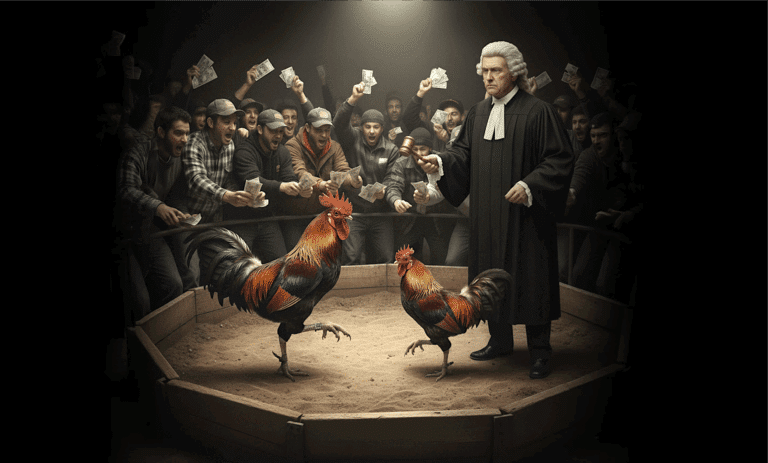

Since Vietnam, civilians have entered the world of warfare as self-appointed military watchdogs. But in doing so, they refract war through the prism of modern civilian ethics, which have no place on a battlefield. For a soldier to perform his or her duty, civilian ethics must largely be broken down in training – particularly that most fundamental ethic, “thou shalt not kill.” Still, many academics continue to analyze past and present wars, publishing revisionist perspectives that locate atrocities among past victories. Yet in doing so, they stigmatize not only the offending act but the soldiers who were sent to commit it. Those soldiers have every right to object. As one Iwo Jima vet put it: “Some people today will tell you it was cruel and inhumane, but you weren’t there – we were.”

In the West at least we have often been particularly hard on the soldiers themselves. Protestors in the sixties spat at American soldiers returning from Vietnam to demonstrate their opposition to the war, even though most of the soldiers were draftees. Two high schools in Germany each received a peace prize this summer from a national NGO for prohibiting soldiers from entering school grounds to recruit, their profession ostensibly too distasteful for the classroom. After a spate of abuse and attacks, British soldiers securing last year’s Olympics were counseled by their commanders to travel in groups and avoid carrying military day sacks or other army identifiers. And Bomber Command veterans were refused recognition for decades because their mission was deemed too controversial. There are certainly cases of soldiers acting dishonourably in battle, and there are court martials to deal with them. But the act of fighting itself is not dishonourable.

I will let you in on a little secret about war: all wars are crimes, but all soldiers are noble. The veterans of the Bomber Command no less so. They braved one of the most dangerous campaigns of the entire war and for decades received little gratitude from the country they served, finding validation only in the shared experience of their band of brothers. No medal is sufficient to honour them. Canadians owe them more than a commemorative bar. We owe them an apology.

They say dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. Although it may not be sweet and right to die for your country, it should be sweet and right to serve. Lest we forget that.

~

Yule Schmidt is a Special Assistant to the Yukon cabinet. She holds a B.A. in History from Stanford University and an M.A. in History from McGill University. This article reflects her personal views and not that of her employer.