The following article is adapted from a presentation to a communications class at Royal Roads University on 8th June 2017.

For 2016, the Oxford Dictionary’s word-of-the-year was “post-truth.” The dictionary defines post-truth as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

In an analysis of the post-truth phenomenon published by The Economist on 10th September 2016, their writer expanded slightly on the Oxford definition, characterizing it as a reliance on assertions that “feel true” but have no basis in fact.

The writer argued that then-candidate Donald Trump is a prime source of post-truth, but he also cited members of Poland’s government who linked the plane crash that killed a previous president with Russian black-ops, Turkish politicians who claimed the perpetrators of the recent bungled coup were acting on orders issued by the CIA, and how the successful campaign for Britain to leave the European Union relied on dire warnings of how hordes of immigrants would result from Turkey’s imminent accession to the union.

The writer recommended that mainstream politicians find “a language of rebuttal… Humility and the acknowledgement of past hubris would help.” So would reliance on democratic institutions – the legal system, and independent bodies that draw on science to inform policy. And, he added, ‘being called pro-truth might be a start.’

With a few narrow caveats, The Economist is right. Only in its cheerful stand-up-and-be-counted solution do I find it to be if not actually wrong, unreasonably optimistic.

Certainly, many things stated with great certainty by public figures are indifferent to empirical fact and logical consistency. Such is the essence of post-truth: Fed enough of it for long enough, we embrace despair and cynicism – we riot or we don’t vote – and we come to believe truth is no longer possible, or even matters.

The truth is, this is not a good time for truth.

But this was not always the case. So, what happened to our democracy? How did we get here?

Three reasons.

First, as a society, as citizens and people, we don’t love truth enough to be truthful. Regardless of facts or evidence, we believe what we want to believe.

And we lie, often.

According to an Ipsos poll last year, two-thirds of Americans think it’s alright to lie in some circumstances. Other studies suggest most of us can’t chat for ten minutes without some untruth. Cheating on resumes is a major problem, 35 percent of Americans believe in flying saucers, and 80 percent of online dating site users juice their profiles.

In these circumstances, why would anybody expect politicians to be careful with truth?

Thus, our struggle with post-truth begins with “we the people.” We must learn to love truth again.

The second is post-modern relativism.

The popular and subversive idea that there are no absolutes, that you may have your truth, and I will have mine, robs us of the shared factual foundations that make reasoned discourse possible.

Black Lives Matter, for example, allows no shared reality. “You’re a white man, you can’t understand my experience as a black woman.”

How then, do you even start a conversation? This rejection of absolute truth – and it runs right through society – is very dangerous. In the end, it leads to tribalism: E pluribus, pluribus.

The third reason people give up on truth is that truth’s institutional gatekeepers – the legal system, academia, science and media The Economist would have us rely upon – are failing.

Let’s start with the legal system. The Supreme Court of Canada, for example, has adopted the post-modern idea that the Constitution is a so-called living tree. Precedent is now no guide to the present. Law must reflect societal consensus. It becomes what nine judges think Canadians think, today.

How fickle can that be?

Well, in the Sue Rodriguez case 20 years ago, the SCOC ruled that assisted suicide was illegal. But two years ago – not even a generation later – it was ruled a human right. And since then, 1,300 Canadians have used physicians to kill themselves…physicians, whose centuries-old profession had famously required of them an oath to ‘first, do no harm.’

Reasonable people can disagree over the merits of assisted suicide. But what trust can a citizen have in eternal verities, if a court can turn a once-absolute truth upside down and inside out in a mere 18 years?

Then there are the provincial human rights codes, where the crime is hurting somebody’s feelings.

Years ago, I seem to recall an occasion when illegal shellfish harvesting in British Columba was the almost exclusive preserve of a particular ethnic community.

That much was known. For a newspaper to report it however, would expose it to a human rights complaint that it had brought “an identifiable minority into hatred and contempt.”

In such cases, truth is not a defence. As a result, the media have learned to leave certain truths unsaid.

In regards to science and academia, anything I say about their failing defence of truth in the short time I have today would sound like a drive-by shooting.

But, the relationship between donors, researchers and results, and the necessity of being on the right side of proper thinking to gain access to research funding, is hotly debated.

Furthermore, the changing role of universities from privileged seekers of truth, to trainers of a workforce raises a serious question: Do professors even have time any more, for serious public engagement on substantive issues?

The news media, meanwhile, has a fascination with conflict. That’s what journalism schools teach because that’s what the public will buy. The problem is that this leads to an emphasis on big personalities and process. Who’s winning this week, who’s sinking in the polls, who’s uttered a killing gaffe will always be more titillating than policy and the balanced prose that better represents the big picture.

Not that readers will ever admit that this is the way they like it. To test our readers’ tastes, I once did a survey in a small newspaper.

The results showed keen interest in city council, the court docket and our editorials. Serious readers we have, I told the newsroom, govern yourselves accordingly.

This was pre-Internet and in those days, the features came page-ready.

Well, about a week later, the Torstar package containing the horoscope, crossword and a column by Ann Landers, failed to arrive and we filled the space with something useful and improving.

That’s when we found what our readers really cared about. The switchboard lit up like a Christmas tree: “Where’s my crossword? Where’s the horoscope? Where’s Ann?

My readers had fibbed, and not just in their pre-Internet personal ads.

That’s why the media don’t go deep on policy, and why they mainly talk about process.

If this is the public taste, it pays politicians to be outrageous.

Even as the media attacked Trump in the most slanted coverage I have ever seen – I have never before seen actual media collusion with a campaign – Trump was still their perfect candidate. Always something to write about, always reliably over the top.

Hillary Clinton, with the odium of scandal ever swirling around her, was a close second.

People got the coverage they wanted and the result was that Americans voted not on agreed facts, but on the facts they were prepared to accept, and how they felt.

Now, I have caveats.

Based on forty years of close observation, I can say that things aren’t always what they seem, nor are they necessarily as bad or worse than they’ve ever been.

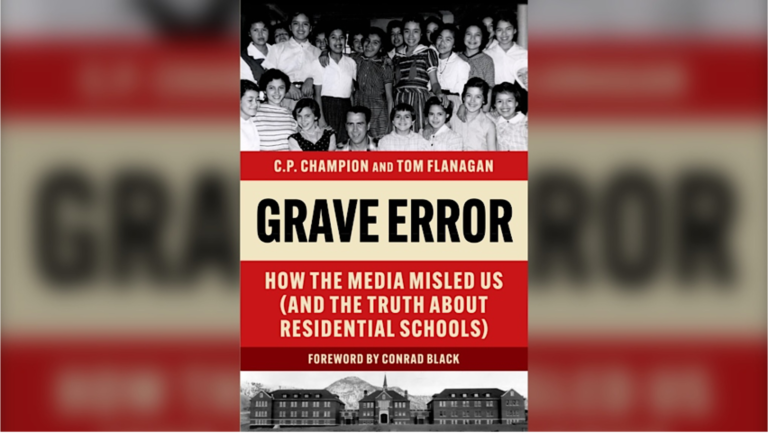

At the Calgary Herald, we were once accused of writing to Conrad Black’s orders, because our editorials on a particular subject were similar in tone, content and conclusion to other papers he owned, notably the Ottawa Citizen and the National Post.

I admit, to any reasonable jury, it would have looked like we all got the same buff envelope under the door every morning. But it just wasn’t so. The truth is we all came to the same conclusions, on our own.

And while I was in the PMO, a very senior retired bureaucrat suggested that we had a sinister plan to confuse public debate on climate change. He made it sound very plausible. The only problem was that however it looked to him, again, it just wasn’t so.

In other words, you cannot reliably deduce intention from outcome. And, it’s something to be wary of: post-truth is so hot that if you look hard enough, you can find it anywhere.

Still, it’s a real problem. So where’s the hope?

Not, I fear, in any overnight recovery of journalistic standards, let alone a post-Trump epiphany of hubris and humility in the Fourth Estate. Welcome as that would be, the bad news is that this is something to pray for, not to bet on.

The public thinks it rewards journalistic objectivity, but it does not.

Neither, sadly, should we place our hopes in a crusading judicial system, or in any establishment that declares the science of anything to be settled.

Through testing theories by experiment, humanity has reached wonderful practical understandings of the way our world works. However, scientists think today rather differently about many a consequential matter than they did a hundred years ago. Even Einstein’s theory of relativity is no longer treated as “settled science” but is being challenged and rethought in many laboratories.

Settled science is indistinguishable from faith, or indeed from the mentality that refuses to hear facts and arguments that undermine the evidence of its feelings.

But, there is good news.

We own the tool that separates truth from a tangle of lies.

The Anglo-American free-speech tradition is messy. Feelings do get hurt, and those who love sausages and good government shouldn’t watch either being made. But when all sides of an issue are examined in the marketplace of ideas, heard and debated, subjected to reason and lubricated on occasion with courage and resolution, out comes the truth. The truth, as we know, sets us free. And enjoyment of our heritage of freedom is what all of this is about.

Not that any of this is easy. We spoke earlier of politically correct forces and how they try to define the parameters of public life, actively trying to silence those who don’t agree with them. Of the three things that got us here, they’re the biggest problem: post-modernism is the mother of post-truth, and subjective evaluations of reality are very much in vogue. But all the more reason, therefore, for us to cling to our free-speech tradition like shipwreck survivors to a raft.

We need to rescue it, or else.

This will indeed take courage. Certainly, it will take engagement. If we do not use it, and stand by others who stand for truth, we will assuredly lose it.

The good news is that isn’t too late. To lift a line from the X-Files, “The truth is out there.” For those who truly desire it, it always will be.