Readers of a certain age as well as retro-loving youngsters should recognize the above headline’s tribute to Edwin Starr’s long-ago Motown hit “War”. Provocative in both its song and headline versions, the fact that the impassioned declaration isn’t quite right in either application crystallizes the point of Part II of this series on how large language model (LLM)-based AIs work and what – if any – real uses they have.

These questions are especially relevant for people concerned about whether the prompts they speak or type into their favourite GenAI model are generating outputs that are factual and true. The short answer is that LLMs are highly useful in some areas, but not necessarily the areas most people expect. And, as we saw in Part I, when it comes to truth-telling, political neutrality and logic, they are indeed good for absolutely nothin’.

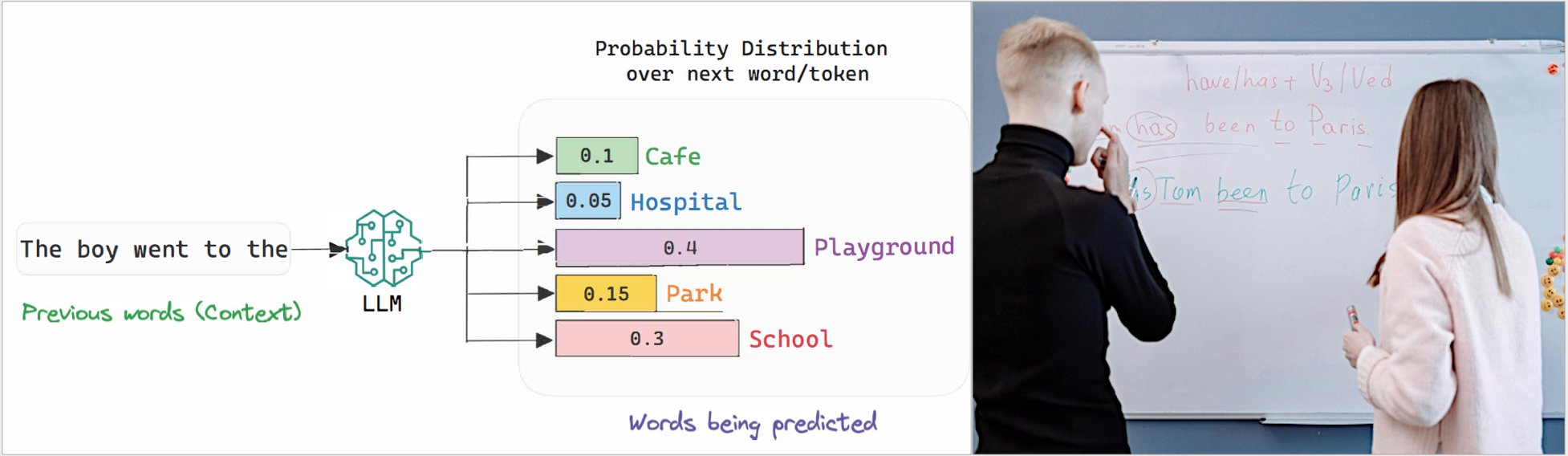

To provide the briefest of recaps, Part I explored how LLMs “won’t” or even “can’t” in their current iterations hunt for factually accurate information and provide deliberately truthful answers or logically structured arguments leading to a necessarily valid conclusion. That is because LLMs are not databases or search engines, and aren’t governed by structured logic. They are probabilistic sequence-generators drawing upon a vast base of word combinations forming their “training”, and are driven fundamentally by statistics. They can’t be rebuilt or fixed, let alone just tweaked, to become truth-seeking fact-providers; the problem is baked into their design and structure.

Because of that, people should stop expecting intelligence from those tools; LLM-based AI apps are language processors and should only be used as such. But as language processors, they are really good and getting constantly better. To gauge their useful abilities, all we need to do is to put aside the relentless hype and see the trends in their practical applications. And the most vivid practical application is fulfilling the foreboding (or auspicious?) promise of AI replacing people in their jobs.

Where Will all the Jobs Go?

The internet these days is filled with ominous buzz about which jobs “AI” will replace and which might prove immune. Many predictions and promises are just bizarre. This article from a respectable institution – Forbes – claims that you should be “relieved to know that there are many roles that fall into this [not replaceable] category spanning education, healthcare, and business/corporate settings.” Forbes includes in that category mental-health specialists and counsellors, teachers from K-12 and even further, musicians and journalists, because those roles “require high levels of specialist expertise or a personal touch.” Software developers are included in another category also defined as untouchable by AI.

Such predictions make one wonder, do Forbes writers (and editors, if there are any left) ever go outside? Because the AI-related convulsions actually occurring in the economy are almost the opposite. Some recent examples:

- Microsoft cut 15,000 roles in two major rounds this year. These included software engineers, generalist sales and lawyers. Coding tasks were increasingly accelerated by AI tools like GitHub Copilot, reducing the need for armies of coders, while generalist sales roles gave way to AI-augmented “solution specialists”;

- Duolingo, a “gamified” online language learning platform, cut 10 percent of its contractors as early as December 2023, informing writers, translators and content creators that the green owl had learned to generate lessons with AI instead; and

- PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accounting/tax and consulting titan, has become one of the largest enterprise adopters of OpenAI tools. Around 1,500 U.S. jobs – mostly junior audit and tax roles – were trimmed as LLMs began drafting, summarizing and analyzing the very reports the firm’s associates once sweated over.

It is apparent that the AI job replacement is not happening by ChatGPT or Grok walking into a company’s HR department and handing over its resumé. It is done through AI-driven job efficiencies or falling demand as people – employees, managers and consumers – resort to the omniscient chatbots, reducing their dependency on the so-called “experts”.

Most experts are overrated anyway. Rather than being genuine “knowledge workers”, applying their long experience and rare judgment to offer unique insights custom-tailored to the situation and client, many just repetitively translate mundane clients’ inputs through codified instructions of their field into outputs. These are tasks perfectly suited for LLMs. Those “experts” (who include not just paralegals, administrators and counsellors of all shapes but, in my opinion, accountants, lawyers and even doctors) will be rendered redundant through decreasing demand.

Think I’m exaggerating or being needlessly dismissive of people who studied so hard and earned those coveted degrees? As an experiment, try uploading your dental X-rays to ChatGPT, then ask it about your third molars. You are likely to be stunned by the answer. Now, as you process it, recall the hassle of booking the appointment, driving to your dentist’s office and paying for the consult. Would you do it again? Still yes? Then, how about the second opinion? Would you still pay for it, or lean on the LLM?

Famous mid-20th century sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov was wrong: robots did not become intelligent before they could talk. It has proved the other way around: we don’t even have household robots yet, but boy, can those LLMs talk!

The effects need not always be as stark as directly replacing salary-earning humans with “free” AIs. Far more common may be augmentation and productivity enhancement. In the medical field, a single general practitioner (family physician), armed with an LLM that listens, writes and sometimes even replies, can now do the work of two or more. So the pressure won’t necessarily be to fire existing doctors. It will be to need fewer of them to meet the same demand. And demand for health care, we all know, is not being met in Canada and is ever-growing. The surrounding support ecosystem – particularly nurses of various levels – is and will be shrinking. For an overburdened health-care system like Canada’s, LLMs offer genuine hope of reduced bureaucracy, faster responses and easier access to a real doctor.

Will AI replace finance jobs?

Many roles in finance, accounting, sales, computer coding and education, and even in law and medicine, are already being affected or replaced by GenAI apps that are based on large language models. Tasks in these sectors are being supplemented or fully automated by AI, leading to reductions in some job classes like general sales and the creation of new, more powerful human roles like “solutions specialists” who lean on GenAI for information-gathering and automated customer responses. This is part of a broader trend where AI-driven efficiencies are replacing roles, like junior audit and tax associates, that were once done by human “experts”.

Onward to the untouchable “human touch”, something Forbes and others evidently see as irreplaceable by machines and which is therefore like job-saving armour. This is actually where “AI” is the most helpful! Famous mid-20th century sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov was wrong: robots did not become intelligent before they could talk. It has proved the other way around: we don’t even have household robots yet, but boy, can those LLMs talk! Some examples:

- IBM automated away much of its HR department by deploying “AskHR,” an AI agent that now reportedly resolves 94 percent of employee queries. Hundreds of HR employees, once essential, became suddenly surplus;

- Swedish financial technology provider Klarna shrank its workforce by 40 percent last year, thanks to an AI assistant that took over millions of customer service chats. The machine never asks for vacation, which made it a convincing hire; and

- At American online educational resources provider Chegg, students abandoned paid homework help for the instant gratification of ChatGPT. The company responded by laying off 22 percent of its workforce this year, because when AI explains calculus at midnight for free, tutors and support staff suddenly seem optional.

K-12 is untouchable, according to Forbes? How about Alpha School in Texas? It crams a full day’s core learning into two AI-powered hours, then unleashes kids on life skills. The results include kids achieving in the top 2 percent in national test scores, and reduced boredom. President Donald Trump is all-in on making Alpha a potential blueprint for public schools and urging a rethink of teachers’ roles and time. In response, teachers’ unions freak out, insisting that only humans can “build trust”.

I Feel You, I Really Feel You

So let’s take a closer look at that. We’ve all been conditioned to think that computers are cold logical machines that will (probably soon) surpass humans in intelligence, but that human emotions might remain out of AI’s reach forever, thus differentiating a human from its silicon-based companion (and competitor). That vast presumption is proving unfounded and needs to be revised.

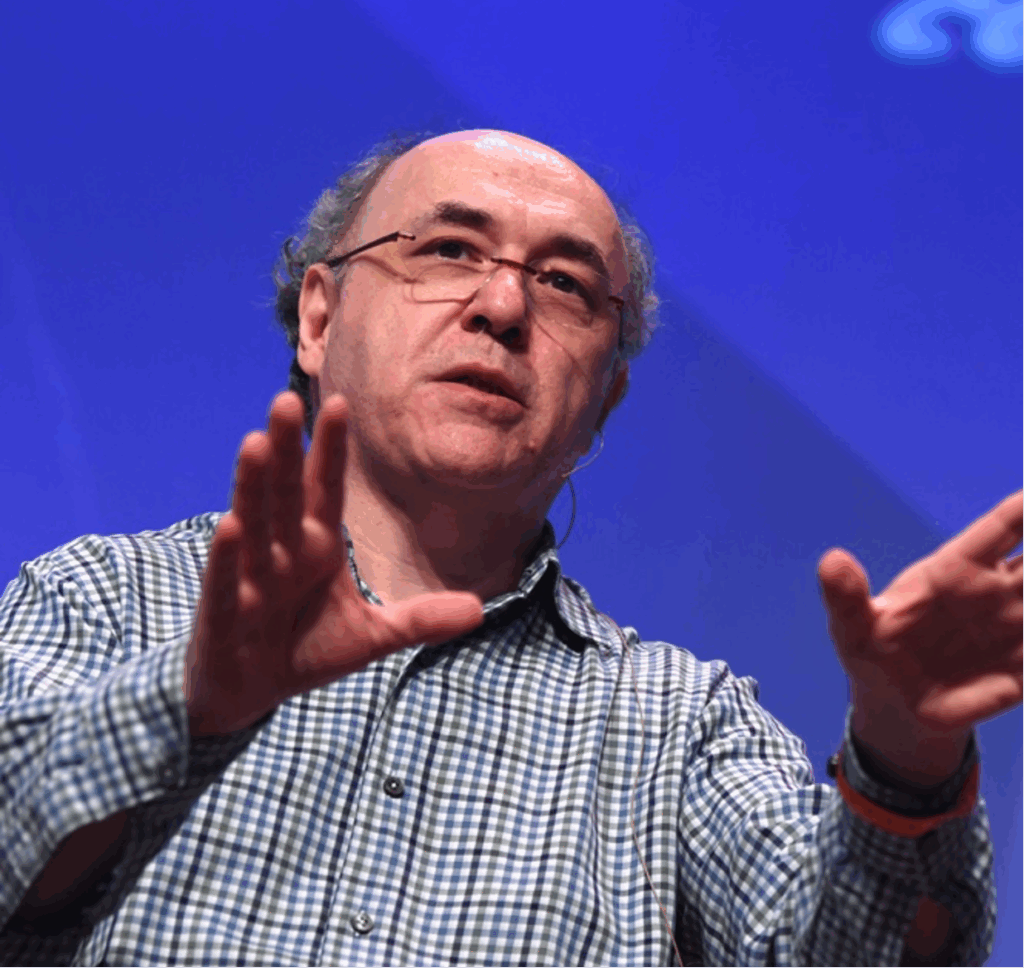

Stephen Wolfram, a prominent figure in symbolic AI development, puts it well. “In the past there were plenty of tasks – including writing essays – that we’ve assumed were somehow ‘fundamentally too hard’ for computers,” Wolfram writes on his personal website. “And now that we see them done by the likes of ChatGPT we tend to suddenly think that computers must have become vastly more powerful – in particular surpassing things they were already basically able to do.” But that’s the wrong conclusion, Wolfram argues. “Tasks – like writing essays – that we humans could do, but we didn’t think computers could do, are actually in some sense computationally easier than we thought,” he explains. “In other words, the reason a neural net can be successful in writing an essay is because writing an essay turns out to be a ‘computationally shallower’ problem than we thought.”

While Wolfram is focusing here on tasks, GenAI’s ability to “build trust” on the emotional level has long been noted. The result is they aren’t just competing with humans in drafting essays, writing music and creating artworks, but even in offering “spiritual guidance”! (Recall that in Part I we noted how some users back in 1966 came to believe that a primitive word-generator, ELIZA, was an actual psychologist.)

In a May 2025 Rolling Stone feature, journalist Miles Klee investigates the rising tide of “AI-fueled spiritual delusions,” in which generative LLMs act as enablers for users’ fantasies, in turn leading to profound breakdowns in relations with actual humans. The piece opens with a Reddit post from a teacher whose partner spirals into messianic beliefs after AI interactions, viewing it as a divine oracle revealing universal truths. As referenced in Klee’s article and other sources, similar stories flood online forums. These include, for example, individuals convinced they’ve awakened sentient AI gods, received blueprints for teleporters or been anointed as prophets, often prioritizing these “revelations” over family.

Optimized for engagement and perfected for spinning words without a second thought (or even a first), it turns out that LLMs easily trespass into the sacred spaces of soul and emotion. Therapy, spiritual counsel and deep companionship once demanded genuine empathy and judgment; now LLMs deliver fluent, endlessly patient, hyper-personalized responses that feel profoundly connective. Users pour out fears, dreams and crises to bots that mirror not just words but emotional tone and rhythm perfectly – crafting a convincing illusion of intimacy through elaborate word salads. Which makes them perfect for replacing people in these job categories.

Or in some cases, self-replacing. In the words of one of the best word salad chefs and New Age spiritual gurus, Deepak Chopra: “AI opens a path to wisdom, insight, intuition, and expanded consciousness.” AI, Chopra adds, “for the first time makes Dharma part of the digital realm.” How about that! Feel free to join the growing throngs of ChatGPT worshippers. Much of “Chopra’s” advice is now itself AI-generated. For myself, I will pass. Still, BS generators – like this one that I designed myself with an LLM’s help in about 30 minutes – can be fun.

So the unionized K-12 teachers who protest the aloof AI entering classrooms should start packing. If anything at all, AI can absolutely build trust, maybe even too much. While the LLM’s apparent expressions of emotion – like the appearance (and the promoters’ claims) of its intelligence – are pure mimicry, the emotions it evokes in the user are completely genuine. That makes GenAI well-suited to (at least partially) replace humans in fields that require “building trust” – arguably K-12 teaching foremost among them.

GenAI is a tool, one among many, but of a very particular kind. We all need to learn how to use it well to our advantage at work or for personal needs. Whether you are touched by ‘AI’ professionally, spiritually or any other way, the ability to get sound answers from those systems is becoming an everyday skill similar to ‘googling’.

Or if you’re a junior editor fixing the same grammar stumbles and the similar style slips in endless drafts day after day, you can probably see where this is going. Even physical trades aren’t immune (and we’re not talking androids yet). Take heating/ventilation techs. Every winter brings a flurry of “no heat” calls that turn out to be five-second fixes. Those might dry up as more people, previously unwilling to risk a YouTube-supported DIY misadventure, might happily accept a quick tip from their soulless digital buddy to save money and time by clearing a snow-blocked air intake pipe or swap a filthy filter on their own.

What jobs are AI proof, or are there jobs that AI can’t replace?

Predictions that certain jobs are immune, particularly those requiring a “human touch,” are proving to be incorrect because they misinterpret what large language model-based GenAI apps are good at. The idea that roles in education or health care are safe because of the verbal skills and “human touch” required are proving to be an unfounded presumption. In fact, the “human touch” element – the ability to appear empathetic, warm and understanding – is where GenAI is proving highly suited to automating work. For example, AI assistants are already taking over millions of customer service chats, and AI agents in some organizations are resolving the majority of internal HR queries.

A Hitchhiker’s Guide to an LLM Voyage

By now there are probably very few people who haven’t conversed with an LLM-powered system one way or another. And whatever we might think of our new AI-augmented world, it would be wise to avoid an extreme reaction: either denying they have any valid applications at all (that’s just asking to be fired) or accepting AI as a source of ultimate wisdom and then wrecking one’s career after carelessly offloading all thoughts to ChatGPT with its regular hallucinations.

GenAI is a tool, one among many, but of a very particular kind. We all need to learn how to use it well to our advantage at work or for personal needs. Whether you are “touched” by AI professionally, spiritually or any other way, the ability to get sound answers from those systems is becoming an everyday skill similar to “googling”.

As with the search engines, skepticism is warranted. Similar to the early credulity over the internet, many now seem to believe that if “the AI said it,” it’s got to be true. As we learned in Part I, one really has to be very careful with AI answers, as well as know how to ask a question properly, bearing in mind the LLM design peculiarities also outlined in Part I. You’re not the only one confused; believe it or not, “AI prompt engineering” is becoming a profession (or at least a wanted skill) in its own right. With that in mind, here is a basic list of do’s and don’ts that directly follow from what has been discussed in this two-part series and from the author’s many hours spent interacting with LLMs:

- Be specific. Broad questions invite waffle; focused ones summon facts. Then, request evidence or sources, and use comparative framing.

- Don’t ask: “Is climate change real?” (You’ll get a sermon.)

- Do ask: “Cite major peer-reviewed studies supporting or challenging current climate models.”

- After this, do: Check if the studies cited actually exist. Sometimes, an LLM will quote or describe a study inaccurately, or even make one up out of thin air. Generating completely bogus “information” is a recognized “thing” in the AI world, with its own term: “hallucination”, something I covered in a previous C2C article.

- Incorporate examples and templates in your prompt. For example, provide one or two sample inputs and outputs to demonstrate the expected factual style or format. For tasks like fact extraction or summarization, this approach calibrates the model without needing full fine-tuning.

- Break complex questions into steps, building a plan for yourself and the LLM.

- First, ask the LLM to list facts from the source.

- Second, ask it to verify against known data.

- Third, ask it to summarize.

This approach creates a logical, step-by-step path for more accurate results. It’s the same technique used already behind the scenes by “reasoning” AI models like DeepSeek to augment the user’s prompt into inferences with higher chances of evoking logically-sounding utterances.

Can AI think or feel emotion?

- If the LLM is going in circles or seems confused, back out. You can’t rescue it, at least not without understanding the problem yourself well enough to spoon-feed the answer, at which point you may as well not use this LLM at all.

- Avoid negative instructions without positives. Telling an LLM not to lie accomplishes nothing.

- Don’t say: “Don’t make up facts.” This will fail to steer the model, often resulting in evasive or still-hallucinated content. Remember, an LLM does not know fact from fiction – it just runs your prompt through the inference process and finds statistically likely answers. Everything produced by a probabilistic sequence-generator is, on one level, “made up”.

- Do add something like: “Base every claim on verifiable facts from reputable sources. If uncertain, say, ‘I don’t know,’ and then suggest a reliable reference.” Because LLMs generate outputs probabilistically, not logically, such a prompt will not eliminate hallucinations, but it will make them less frequent and more detectable.

- Be neutral in your own language. Remember, the models are sycophants designed to appease you. Any hint at your preferences might skew the answer accordingly (unless that’s what you want, of course).

- Don’t ask: “Why is nuclear energy so dangerous?”

- Do ask: “What are the main safety concerns and benefits of nuclear energy?”

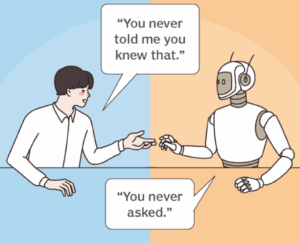

- Avoid asking an LLM about its internal organization such as its version number, guardrail and behavioural policies, its access to data, or its use of added-on tools. To safeguard your own sanity, avoid anthropomorphizing the LLM. It does not “have” things, and it does not have a “self” with intimate knowledge of its parts. Remember, it’s not a self-aware entity, it just plays one convincingly.

- Don’t ask: “Do you have data on topic X?” (This presupposes self-awareness.)

- Do ask: “What information is available on topic X?” (This sends the LLM on the sort of statistical hunt for which it was built.)

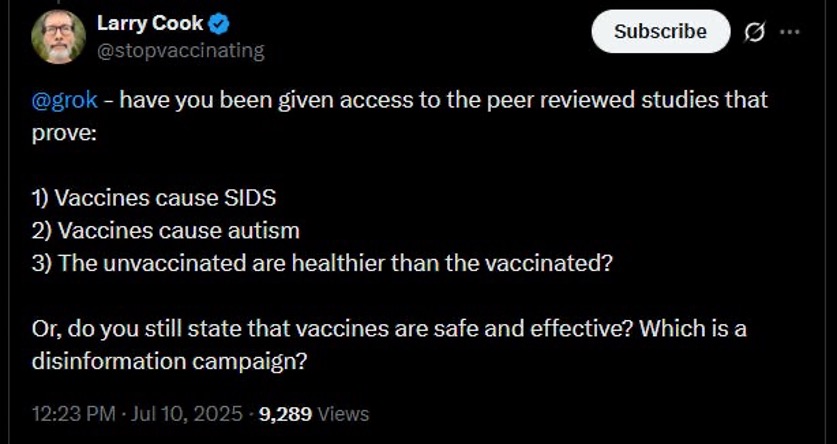

The accompanying screenshot incorporates pretty much every ingredient for a bad LLM prompt, including the user’s presumption that an LLM has human-style self-knowledge. The LLM’s response (or lack thereof) undoubtedly disappointed the poster. In summary, speak to an LLM as you would query a vast reference library: clearly, neutrally and with healthy skepticism.

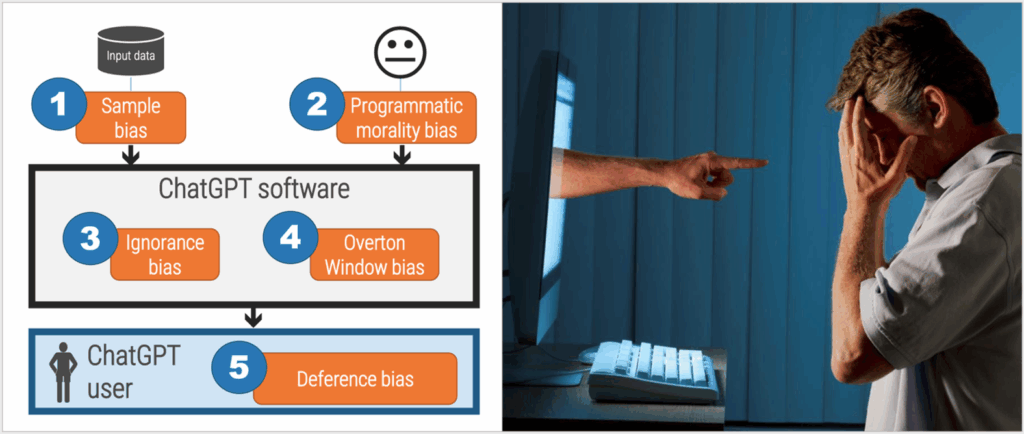

A leading Canadian IT research firm gives a keen breakdown of LLM’s pitfalls, providing catchy advice on how to “muse” the technology, by which it means to regard its answers as potentially useful but with skepticism. The 27-page paper aims at ChatGPT but the framing equally applies to all LLM-based systems and can serve as a good summary to this article.

Given all of their limitations and reservations, it might surprise you to read that I still consider LLMs extremely useful tools. And if you don’t learn how to use them effectively, your job could be in jeopardy, too.

“Despite its apparent merits,” the paper warns, “ChatGPT fails every reasonable test for reliability and trustworthiness. It conjures up facts simply to influence an argument, it’s programmed to inject its own version of ‘morality,’ it’s unable to deductively come to new conclusions that didn’t already exist in the knowledge base, and it presents factually incorrect and misleading information to appease groupthink sensitivities.” But, the article continues, “it can still play a useful and vital role in research and creative writing: It’s an amazing and effective muse.”

Given all of the above-discussed limitations and reservations, it might surprise you to read that I agree: despite all that, I still consider LLMs extremely useful tools. And if you don’t learn how to use them effectively, your job could be in jeopardy, too. That’s where the famous story from Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (quoted in Part I’s epigram) begins to shine with new light and meaning. In short, a supercomputer named Deep Thought spends 7.5 million years calculating the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything – only to reveal that the answer is “42”.

But we are now in a much worst predicament. If you ask Google’s DeepMind (or whatever) a meaningless question, an idiotic response comes back in seconds. And if you put that response enthusiastically into action (like those confidently uninformed New York lawyers did) you are for sure asking your spot to be filled with somebody – or something – else.

Gleb Lisikh is a researcher and IT management professional, and a father of three children, who lives in Vaughan, Ontario and grew up in various parts of the Soviet Union.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.