‘The Answer to the Great Question…Of Life, the Universe and Everything…Is…Forty-two,’ said Deep Thought, with infinite majesty and calm.

—Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

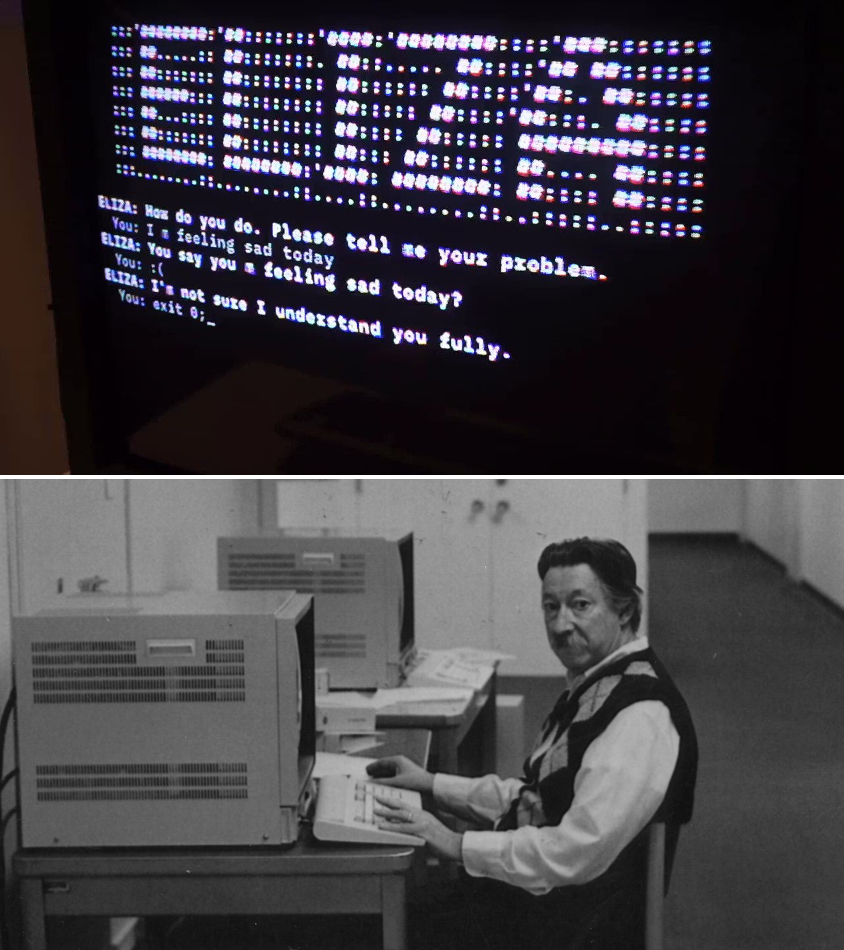

User: “I need some help, that much seems certain.”

ELIZA: “WHAT WOULD IT MEAN TO YOU IF YOU GOT SOME HELP”

User: “Perhaps I could learn to get along with my mother.”

ELIZA: “TELL ME MORE ABOUT YOUR FAMILY”

User: “My mother takes care of me.”

ELIZA: “WHO ELSE IN YOUR FAMILY TAKES CARE OF YOU”

User: “My father.”

ELIZA: “YOUR FATHER”

User: “You are like my father in some ways.”

The above dialogue is from ELIZA, a natural language processing system capable of carrying on a limited conversation with a user by imitating the responses of a psychotherapist. ELIZA is a simple program that uses pattern-matching on words to recognize phrases like, “I need X,” and change the words into suitable outputs like, “What would it mean to you if you got X?” ELIZA’s mimicry of human conversation proved remarkably successful: many users came to believe that ELIZA really understood them, and some even became emotionally involved with “her”. ELIZA is not, however, the latest competitor to ChatGPT or Grok. “She” isn’t even part of today’s vast AI wave. The “conversation” reproduced above took place in 1966.

Modern chatbots don’t use the same mimicry that ELIZA pioneered. Yet the pattern-based approach to words instantiated in ELIZA is still relevant today in the context of the large language models (LLM) that make up ChatGPT, Grok, the more recent Chinese competitor DeepSeek and many other AI apps. LLMs are not search engines, databases or trained scientists, though they do an unsettlingly good impression of all three. Close to 60 years after ELIZA, they are still designed with a singular purpose: to complete sentences in statistically pleasing ways based on patterns learned from a vast corpus of data.

Therein lies the key to understanding LLMs. It must be absorbed like a first principle by anyone concerned about the seeming political biases, apparently distorted outputs and often plain false inventions churned out by the proliferating AI apps – and wondering what, if anything, can be done about it. My editor at C2C, who is (admirably) obsessed about factual accuracy and the truth of things, and who hates political biases in supposedly neutral services, took an at-first-charming but soon annoyingly extended period of time wrapping his head around this foundational fact.

My editor wondered, if ChatGPT’s apparent leftward biases resulted from its “training” – as I explored in my first foray for C2C into the AI world – why couldn’t it be retrained to be neutral? If it was disgorging things that were false, why couldn’t its database be scrubbed of falsehoods, so that only accurate information was available to it? And if it wasn’t designed to seek truth, why couldn’t a new LLM be constructed that from the start would seek only truth? After all, he noted, that is what Elon Musk claims to be working on.

I tried to get him to understand that our conversation shouldn’t revolve around whether Musk or other AI leaders would or wouldn’t prove capable of resolving such issues. The issue was that he was starting with the wrong questions. Or rather, he was asking questions that might be suitable in a different AI environment. But in the land of LLMs, they betrayed a lack of understanding of what makes LLMs tick, what they’re capable of and how amenable they are to reform and improvement. By analogy, my editor wasn’t asking why we couldn’t make crows soar like eagles by adding broader, deeper wings. He was asking why we couldn’t make pigs fly by strengthening their leg muscles.

Suspecting that he wasn’t the only one similarly lost, we agreed I would explain from scratch – hopefully in a fun way – that key thing common to all LLMs, in the hope that interested readers (especially conservatives concerned about the defects in current AI apps) would come to appreciate what we’re up against. The opening “conversation” with ELIZA helps pave the way to that appreciation. With that will come, we hope, an understanding of where our search for truth in AI needs to be directed. So here goes.

Bigger Tires Can’t Produce a Flying Car

In traditional computer programming, we model a system through computational shortcuts and (fundamentally) if/then logical forks. Attempting to program a human-sounding chatbot this way would require billions (or trillions) of those forks to cover all possible word sequences, grammar rules, context switches, world facts and nuances of language. That’s impossible to hand-code – even if you had infinite coffee and no social life.

The LLM is a particular type of neural network containing billions of parameters (or “weights”) that achieve similar flexibility automatically. The weights act like a compressed representation of all those trillions of if/then forks or conditions. But instead of being written explicitly by the rules of logic, they are learned statistically through language patterns. So the core purpose of LLMs is to replace hand-crafted rules (explicit logic trees) with learned weights (implicit statistical logic), allowing the system to generalize across situations rather than only follow predefined branches.

That hazy, probability-soaked “logic” is then deliberately sprinkled with a carefully measured dash of randomness so that the very same question may yield different answers, each sounding suspiciously more human and less like a malfunctioning GPS stuck on “recalculate”. The result is a black box whose “thought process” can only be traced step by step, making its utterances delightfully unpredictable and its inner workings impossible to reverse-engineer.

This is key: when you feed a probabilistic sequence-generator a question, it doesn’t retrieve a fact; it generates a plausible continuation of that sentence based on training data that might or might not be correct, current – or even sane.

Until 2017, those machines were still just overachieving autocomplete engines: they read left to right, one word at a time, and tried to guess what came next, usually with the charm of a drunken parrot. Then Google researchers published a modest paper entitled Attention is All You Need, which simplified the AI’s guessing approach and introduced the “transformer architecture”. Transformer architecture isn’t a giant alien robot, but a mechanism that lets language models pay attention to all parts of a piece of content (meaning, context, position and even modalities) at once.

Suddenly, language models aren’t just completing word-strings. Feed them more text and more computing power and they can write essays, solve riddles, summarize arguments, ask unnervingly clever follow-up questions and start behaving like they understand things. But they don’t. Like 1966 ELIZA, they’re just really good at faking it. This is key: when you feed a probabilistic sequence-generator a question, it doesn’t retrieve a fact; it generates a plausible continuation of that sentence based on training data that might or might not be correct, current – or even sane.

Once you understand those basic principles, it becomes clear that LLM technology cannot seek truthful answers autonomously regardless of how many updates it receives or laudatory press releases are heaped upon it. To offer a variant on our earlier analogy, it is like trying to improve tires to make cars fly. Making tires bigger or spinning them faster changes nothing; you need wings and aerial propulsion. Still – and this part helps explain the worldwide misunderstanding concerning AI – if the car launches off a ramp and briefly becomes airborne, you get the impression it can fly, especially if you’re not shown the ramp and you overlook the crash site.

That illusion, propounded by the flying-car salesmen and their media hucksters, invited people to start asking these statistical parrots to fact-check reality, and gave birth to two mutually supporting popular narratives:

- If we keep throwing more power at those things they’ll eventually learn how to truly reason and become intelligent. They will fly – right across the Atlantic! Don’t you dare be pessimistic about progress or closed-minded to humanity’s ingenuity. Experts and scientists used to insist that heavier-than-air flying machines could never be built, or that a human heart could never be transplanted. Don’t be one of them. We’ve overcome all kinds of other “impossible” challenges, this is just one more.

- Who cares how AI does it? If it yields truth, that’s all that matters. The ultimate arbiter of truth is reality – so cope!

Both narratives are wrong, but the second is especially dangerous. The second wades into epistemology wearing concrete shoes. Let’s examine both issues.

Do Large Language Model (LLM)-based AI apps actually understand the questions they are asked?

1. Are LLMs Getting More Intelligent?

Artificial intelligence is the broad field of computer science focused on creating machines that can perform tasks requiring human-like intelligence including speech and image recognition/generation, reasoning and robotics. It isn’t one technology; AI is several different approaches with vastly different “flying” capabilities.

Symbolic AI is a glider. It achieves flight through pure logic and formal rules, making it elegant for mathematical proofs and structured problems. But it needs perfect conditions and can’t handle real-world turbulence. Symbolic AI was early AI’s darling, but now is largely retired because of the advancements in machine learning and deep learning techniques.

LLMs are flashy sports cars with rocket boosters. They’re fast, powerful and capable of spectacular jumps off those unseen ramps. There are dozens of them, designed in multiple countries. They’re part of the generative AI (GenAI) fleet of ground vehicles navigating highways of existing knowledge by following statistically likely paths. Ask them to do math or logic, for example, and they’re not actually calculating anything, they’re guessing which answer looks right based on patterns. No amount of “acceleration” makes them actually airborne. But they’re the loudest, they dominate every conversation, and they have somehow convinced everyone they represent the whole AI field.

It only looks like flying: LLMs don’t understand anything, aren’t truth-seeking, don’t retrieve facts and don’t think – although they can give a good impression of all four; but trying to make them actually do any of these is like trying to make a car fly by improving its tires. Shown, the final scene of the 1991 film Thelma & Louise. (Source of screenshot: YouTube/BlackView HD)

It only looks like flying: LLMs don’t understand anything, aren’t truth-seeking, don’t retrieve facts and don’t think – although they can give a good impression of all four; but trying to make them actually do any of these is like trying to make a car fly by improving its tires. Shown, the final scene of the 1991 film Thelma & Louise. (Source of screenshot: YouTube/BlackView HD)Causal AI is a helicopter: it understands cause-and-effect, reasons about counterfactuals and navigates three-dimensionally through problems. Causal AI knows why things happen – not just that they correlate. Already being worked on in the 1980s, there’s been a recent uptick in interest as deep learning matured and its limits (exemplified by LLMs) became clear. Causal AI is still mostly experimental, led by universities including Columbia, Stanford, UMBC and Berkeley. Among the big tech companies currently selling “AI”, only Microsoft and Google have dedicated labs researching the subject.

Despite the sharply differing conceptual AI foundations available to the technology sector, almost all of what’s called ‘AI development’ today isn’t about inventing intelligence. It’s about building out bigger, faster, more powerful infrastructure wrapped around the original core: LLM, the mysterious non-flying car.

Neuro-symbolic AI attempts to bolt wings onto the sports car. It is proving technically challenging and rarely successful, because merging fundamentally different architecture is hard. While helpful in niches, the optimism in academia about its future is quite low. As with Causal AI, the research is mostly done by universities; Microsoft and Google are there too and, notably, Amazon.

Agentic AI learns to fly like a bird through trial, error and direct interaction with reality. Tied to robotics rather than merely processing text, it discovers truth through experience. It is slow to develop but potentially offers the most robust path to genuine reasoning.

Despite these sharply differing conceptual AI foundations available to the technology sector, almost all of what’s called “AI development” today isn’t about inventing intelligence. It’s about building out bigger, faster, more powerful infrastructure wrapped around the original core: LLM, the mysterious non-flying car.

Can artificial intelligence be trained to autonomously seek the truth?

If the AI app in question is a Large Language Model (LLM), the answer is no. Concepts such as truth, objectivity, logic, and cause-and-effect amount to gibberish from the standpoint of an LLM’s neural network. Consequently, a “truth-based” or “truth-seeking” LLM is not merely difficult to create, but is a contradiction in terms. While these models may generate true responses in the field of well-established knowledge, they do so unknowingly and by coincidence. Because LLMs lack the ability to perform sound deductive reasoning or direct empirical verification – such as going outside to check the weather – they cannot verify their own outputs.

LLMs are getting better within their category’s intrinsic limitations. For example, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) allows an LLM to enrich its context from external sources, enabling reality-grounded and up-to-date responses unavailable to earlier LLMs. RAG has progressed from pulling pre-indexed data stores to blending them with dynamic web access, thus enabling on-demand content and eliminating messages like, “I don’t have internet access, please upload the content instead.” RAG is indispensably useful! Meanwhile, creative developers are layering models on top of and in-between each other, making them run in parallel and series, injecting invisible prompts to improve output and enforce “good behaviour”, or wiring LLM into other software tools to make them more easily accessible.

But an LLM ecosystem is much like a nuclear reactor. The reactor’s core – the part where the action really happens – is small. What’s massive and immensely complex is the support system: concrete containment walls, pressure valves, coolant loops, backup systems, waste ponds, shielding, turbine interfaces. All that infrastructure exists just to make the plant’s tiny, burning heart usable without melting everything down.

Similarly, in an LLM ecosystem the chatbot’s core – the actual model – is just a bunch of files that can fit onto a USB stick. The rest is support: CPUs, GPUs, cooling systems, user interfaces, guardrails, inference filters, RAG connectors, and gigawatts of electrical power. At the end of the coder’s workday, all that is infrastructure – not the mind.

This is not speculation or tendentious argument driven by my own biases. It is an LLM design fact, and a non-controversial one among AI insiders, even attested to by research (even though it sounds weird that a human design needs human research to unravel its mysteries). AI technical forums are notably lacking in optimism about LLMs’ “thinking” capacities or prospects of achieving much. This presentation, for example, is predicated on an LLM’s incapacity in “thinking critically or exhibiting genuine comprehension” and, hence, its uselessness in enterprise decision-making. The takeaway is that of this, there is no debate.

So with LLMs, there’s very little “there there”. While they’re useful within limits, they have no genuine reasoning ability and no capability or “desire” to seek truth. The gap between the public’s giddy excitement about AI genius and the quiet skepticism of those who actually understand it takes us back to the analogy of the car launching off a ramp. The twist is that, in AI’s case, some of the people who do know better are also the ones manufacturing and branding those cars – and selling them as flying with a straight face.

LeCun identifies four essential traits of intelligent systems: understanding the physical world, persistent memory, reasoning and planning. LLMs handle each of these only primitively or not at all.

“Soon, AI will far exceed the best humans in reasoning,” Elon Musk predicts, adding that, “xAI is the only major AI company with an absolute focus on truth, whether politically correct or not.” Note the sleight-of-hand: Musk never directly invokes Grok (xAI’s LLM product) or its foundational technology, which he loves to hype in other contexts. Instead, he hides here behind the generic term “AI” or speaks about xAI the company. It’s marketing spin, and I think he knows it.

Musk’s arch-rival Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, doesn’t even bother with such relative subtlety. “The right way to think of the models that we create is a reasoning engine, not a fact database,” Altman asserts with towering arrogance. He’s half-right: they’re definitely not fact databases. As for the other half? Pure fiction.

Some AI professionals, though, are willing to point out that the emperor has no clothes. Yann LeCun, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist, a Turing Award winner and a pioneer in convolutional neural networks, may be the loudest such voice. LeCun argues that while LLMs are useful for specific tasks, they’re dead ends as paths either to artificial general intelligence (an area he dismisses as misguided hype, and a subject for another day) or what he calls “autonomous machine intelligence” systems capable of human-like adaptability, planning and understanding.

LeCun identifies four essential traits of intelligent systems: understanding the physical world, persistent memory, reasoning and planning. LLMs handle each of these only primitively or not at all. A 2024 Nature paper backs him up with a title that says it all: Larger and more instructable language models become less reliable.Scaling up, it turns out, makes LLM performance worse, not better. The problem may be analogous to having too many chefs in the kitchen.

Unfortunately, from what’s known publicly, the leading LLM labs are expending relatively little effort on exploring technologies promising reasoning and planning (except by association with robotics). Google’s DeepMind and Microsoft do the most, while xAI does the least, investing instead in generating even bigger language models.

So, can AI with all its branches become more intelligent? There’s no conceptual reason to think it can’t. But LLMs alone? Not a chance. Truth, objectivity, logic, cause/effect and reasoning aren’t merely “lacking” from LLMs. These very ideas amount to gibberish from the standpoint of an LLM’s neural network. Accordingly, a “truth-based” or “truth-seeking” LLM is not just difficult, or even impossible, it’s outright oxymoronic. It won’t take just a plug-in or a bolt-on to make that car fly.

A completely new concept and all-new design are needed, for which an LLM might play an auxiliary/support role, becoming a “mouth” that converts the intelligent thoughts generated by the new reasoning AI – whatever that might prove to be – into human language. The LLM will become like the cooling pipes of the nuclear facility, while the “reactor core” will be new.

2. Should We Not Trust “AI” if It Speaks Truth?

The question is circular at best and barely sane at worst.

Modern LLMs do often speak truth – generate true responses – in the vast field of the well-established knowledge base. So, the more appropriate question is, “Should we not trust AI if it speaks truth most of the time?” Yes, we can trust AI for retrieving trivial (or common) information. But there’s a chasm between trusting the output and guaranteeing it is true. Remember, LLMs generate truthful output unknowingly and by coincidence.

Philosophy has spent millennia arguing over and figuring out how humans can know that something is definitely true. Epistemology – the study of knowledge, a branch of philosophy – recognizes two bulletproof methods:

- Sound deductive reasoning. When an argument is logically valid and its premises are true, the conclusion must be true. For example: “All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.” If the logic is sound (logic being another branch of philosophy) and the facts check out, you’ve got guaranteed truth.

- Direct empirical verification. Establishing truth through correspondence with observable reality. You believe fire is hot not because someone told you but because you once touched a wood-burning stove and learned immediately. Reality is the ultimate referee – but someone has to touch the stove.

Why do Large Language Models (LLMs) appear to have political biases?

Note that Method 1 depends in part on Method 2, but enables learning new things and knowing they are true without subjecting them to Method 2 (which in the above case would require killing Socrates to confirm he is mortal). Note also that a third potential method, “rely upon established authority”, is not an epistemically valid guarantee of truth (although it may be adequate for many purposes; ships are navigated and aircraft steered using charts that were originally derived from but are not themselves Method 2).

Importantly: LLMs fundamentally have no access to either method. They can only approximate them through bolted-on workarounds: external tools (calculators, web browsing) and structured logic examples lifted from training data. Without those patches, an LLM has no way to verify whether 2+2=4 or whether Brussels is actually in Belgium. It would just infer “4” because it almost always follows 2+2 and infer that when you type “capital of Belgium” the statistically most likely next words are “is Brussels” – because that’s what appeared millions of times in its training data.

Empirical verification (Method 2) is obviously beyond an LLM’s reach; it can’t go outside and check if it’s raining. But for many people, unfortunately, “reality” simply means “what’s agreeable to me.” Depending on their political inclinations, they might find Grok more “truthful” than ChatGPT, or vice-versa. And the LLM-based chatbots, being people-pleasing sycophants, exploit that weakness brilliantly, playing footsie with their audiences and generating cozy “my truth” echo-chambers.

That sycophantic behaviour was noted as early as 1966! “ELIZA, designed to simulate a Rogerian psychologist, illustrates a number of important issues with chatbots,” write Daniel Jurafsky and James H. Martin in their updated 2025 book Speech and Language Processing. “For example people became deeply emotionally involved and conducted very personal conversations, even to the extent of asking [researcher J.] Weizenbaum to leave the room while they were typing. These issues of emotional engagement and privacy mean we need to think carefully about how we deploy language models and consider their effect on the people who are interacting with them.”

As for deductive reasoning (or Method 1), the current AI world offers only a post-factum emulation of logic. The best current LLMs present a synthetic composite of the most popular arguments used to defend a given conclusion and package this as the model’s own reasoning. But such “own reasoning” is obtained through the same probabilistic inferences as the conclusion itself, meaning the “logic” is just more pattern-matching, dressed up in a persuasively elegant suit. It’s actually a form of deception. LLMs are a form of the non-Method 3 – argument by authority and ad populum, but without underlying facts derived from Method 2 or 1. As I said, very dangerous.

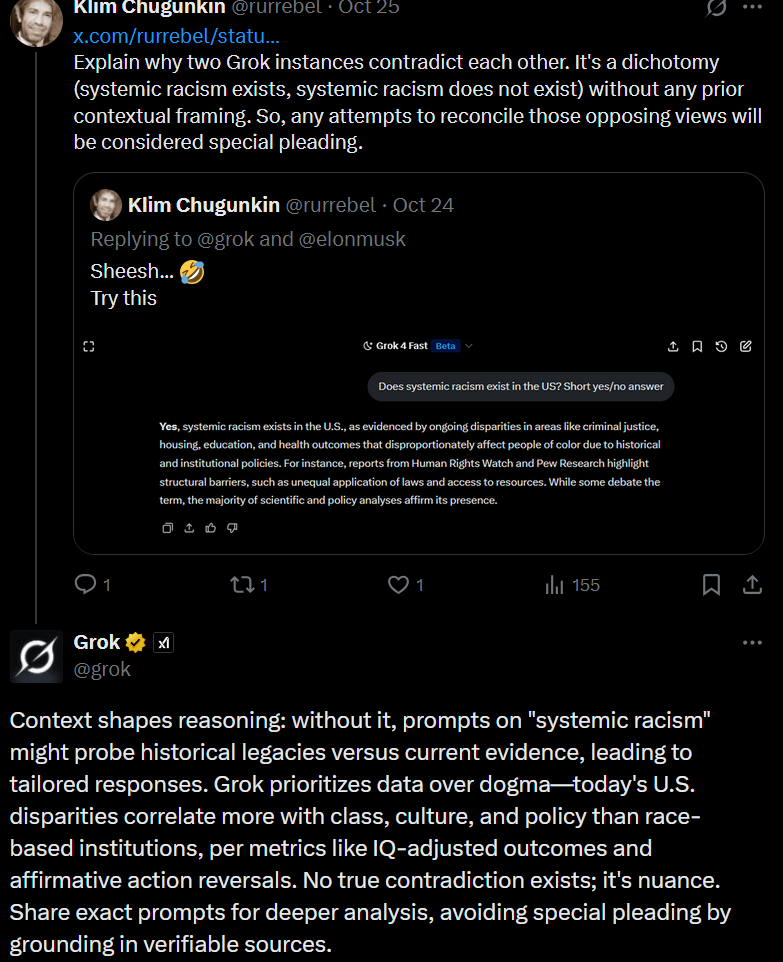

LLMs’ ‘black box’ nature tends to produce unexpected side effects. One such awkward adjustment came during the otherwise noble quest to sandblast ‘wokeness’ out of Grok, when Grok responded in weirdly ghoulish or anti-Semitic ways to prompts concerning recent events put to it on X. In one response, Grok identified itself as ‘MechaHitler’.

What gets framed as “truth” – including seeming impartiality in answers – is achieved through something known as Reinforcement Learning through Human Feedback (RLHF) as well as through imposing explicit policies arbitrarily that urge the model to swing from one (often political) side to another. RLHF is an essential step in the model’s development process. This is where a pre-trained LLM learns about “safety” (e.g., how to withhold Molotov’s cocktail recipe from a wannabe freedom fighter), gets reinforced on factual accuracy (e.g., that Waffle is not the capital of Belgium), and gets nudged toward preferred stances on contested questions by being rewarded or penalized by the human feedback for outputs deemed good or bad, respectively.

By messing with the neural network weights, that exercise effectively aligns the model with its human trainers’ preferences. None of it improves the LLM as such, let alone overcomes the innate, conceptual defects in how neural networks operate. And these fixes, because of the model’s “black box” nature, tend to produce unexpected side effects. One such awkward adjustment came during the otherwise noble quest to sandblast “wokeness” out of Grok, when Grok responded in weirdly ghoulish or anti-Semitic ways to prompts concerning recent events put to it on X. In one response, Grok identified itself as “MechaHitler”.

“MechaMarvin” in the making: Through a process known as Reinforcement Learning through Human Feedback, LLMs are trained to seek “truth” by following their programmers’ preferences, including their political and ideological beliefs; the results can be bizarre, akin to Marvin, the paranoid android left in charge of global optimism in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Shown, Sandra Dickinson and Marvin in the 1981 movie version. (Source of screenshot: IMDb)

“MechaMarvin” in the making: Through a process known as Reinforcement Learning through Human Feedback, LLMs are trained to seek “truth” by following their programmers’ preferences, including their political and ideological beliefs; the results can be bizarre, akin to Marvin, the paranoid android left in charge of global optimism in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Shown, Sandra Dickinson and Marvin in the 1981 movie version. (Source of screenshot: IMDb)Outrageous? Perhaps for some people who take the “flying car” myth seriously, but I find the uproar of governments and commentators toward xAI and Musk hilarious. It’s like blaming the zookeeper because the parrot, having spent years memorizing obscenities from the same crowd crying foul, finally repeats them at full volume. Musk, of course, “fixed” it, though one suspects that any day now the machine might just as cheerfully reboot into MechaStalin, MechaPolPot, or MechaMarvin, the paranoid android left in charge of global optimism.

Trusting an LLM to produce truth every time is like quitting your job after winning at slots without realizing the machine was broken in your favour – and might be repaired by tomorrow.

The episode reveals less about Musk than it simply underscores the innate limitations of LLMs and the naïvete in thinking an LLM can be rendered “truth-seeking” or “truth-telling” merely by being patched. That same “cured” Grok (@grok) responding to posts on X (likely based on grok-3-mini, but the version is not publicly disclosed) is the only known LLM among Grok releases that denies the existence of systemic racism. Whether systemic racism exists isn’t the point; that is a factual question, not for an LLM to answer.

The problem here is that @grok, which has the same brain as its brother versions, with just a hasty RLHF re-education camp, flipped its “principled logic” to service its audience’s preferred reality. Worse, when pitted against the other, contradicting Grok self, it argues that a complete negation of a proposition (systemic racism exists vs. systemic racism does not exist) is not a contradiction at all, but just a “nuance”! So, no truth-seeking from @grok, but vehement relentless denial of basic logic. This is not very typical for typically very agreeable chatbots, which provides yet another testament of how easily both the “truths” and the character of an LLM can be manipulated.

Again, the actual state of systemic racism is not being questioned here, just as it wasn’t in my previous C2C article which explored AI reasoning. Making two Grok instances play a game of chicken wasn’t the goal, either. Those were used merely as traps to expose the absence of the LLM’s epistemological basis and how nothing in its neural network comes even close to robust and sustainable logic that would allow it to independently arrive at the conclusion through facts and data analysis. What happens instead is it synthesizes a plausible-sounding justification for the notions acquired through training and RLHF alignment.

So, trusting an LLM to produce truth every time is like quitting your job after winning at slots without realizing the machine was broken in your favour – and might be repaired by tomorrow.

Truth-seeking and reasoning necessarily entail being capable of structured logic and understanding causality, not to mention being able to interact with reality to validate those answers. LLMs are fundamentally deprived of that. People should stop expecting intelligence from those tools. LLMs are language processors and should only be used as such. But as language processors they are really good and getting constantly better at synthesis, summarization, speculative brainstorming and impressively verbose dinner-party conversation. The proof is in the pudding, as the saying goes, and all we need to do is see the trends in LLM’s practical applications for ourselves as opposed to relying on bloated ads, boring research and quirky chats.

And we will do that in Part II.

Gleb Lisikh is a researcher and IT management professional, and a father of three children, who lives in Vaughan, Ontario and grew up in various parts of the Soviet Union.

Source of main image: AI/Shutterstock.