The most expensive words I ever said were “Condo art.”

I meant it as a compliment to the superior decorating skills of the woman who would become my wife. Superior, that is, to the commercial hotels I frequented, with their green paint, rosewood furniture, and peppercorn ducks… And those fading prints of Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party in the restaurant, its rich gastronomy contrasting bleakly with the meagre fare upon my plate.

It was the ’90s. She had just put the finishing touches on our new place. “Nice condo art,” I said.

“Pure bloody kitsch,” she heard. And went shopping.

These days, our condo is adorned with a considerable investment in “Nice modern art.” We like it. But, as conservatives, we feel a bit conflicted. Can pictures “my kid could have painted” be conservative art?

Our conservative friends say they like it. Even friends who have Thomas Kinkade prints on their walls. And our kids find it encouraging.

So there these pictures hang, and we live with the cognitive dissonance. But, are we enjoying forbidden fruit?

Artistically, the left advocates for revolution and utopia through the avant garde, and the abandonment of rules, restraint and often technique. But does that mean conservatives can only express themselves through formalist, traditionalist approaches to art?

One of the better known conservative contemporary artists in the world today is Provo, Utah painter Jon McNaughton. We know he’s a conservative because he loudly self-identifies as one. And because conservatives like him, and liberals don’t. Steven Colbert has skewered him, as has Rachel Maddow. New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz described McNaughton’s paintings as “bad academic derivative realism”, “propaganda art” and “visually dead as a door nail.”

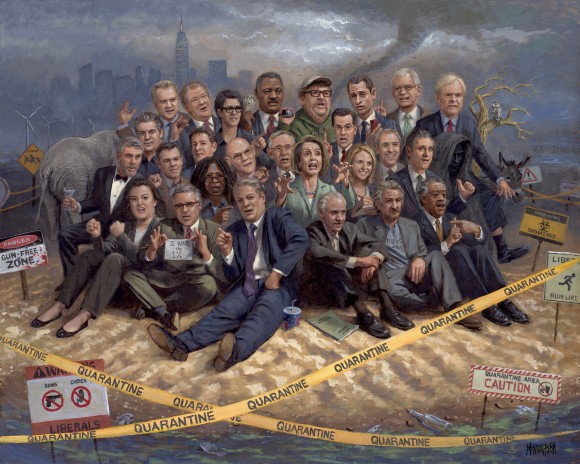

McNaughton paints overtly conservative themes and resolutely anti-left subjects. His 2013 piece, Liberalism is a disease, depicts two dozen prominent members of America’s liberal media and political elite (plus Mitt Romney), quarantined in a “gun-free” zone. (Pure imagination, alas.)

And, he uses the traditional, formal, realist style. In his One Nation Under God, the crowd of characters flanking Jesus include recognizable facsimiles of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Ronald Reagan and many other historical figures amongst a host of generic icons of American culture. In short, the oft-described “artist of the Tea Party” ticks all the conservative boxes, and none of his work leaves any room for misunderstanding of his political bias.

Some conservatives find McNaughton’s dearth of subtlety off-putting, ham-fisted, and even embarrassing to their cause. They prefer the paintings of a conservative artist like Atlanta’s Steve Penley. His work is also unmistakably conservative in its choice and treatment of subjects, but his style is modern and abstract. According to a 2015 profile in the Atlantic Monthly, Penley’s art is much favoured by conservative intellectuals like the late Andrew Brietbart and pollster Frank Luntz, and Republican heavyweights like Senator Ted Cruz and House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy.

McNaughton and Penley are unambiguously conservative, both in their art and their public personas. But the life and work of another American painter, the late Andrew Wyeth, demonstrates that one can be a conservative artist without being obvious and noisy about it.

Like McNaughton, Wyeth was a formalist in a modernist time and thus he endured more than his fair share of critical disapproval. But his work was (and is) widely appreciated and occasionally defended. “In today’s scrambled-egg school of art, Wyeth stands out as a wild-eyed radical,” observed one critic in 1963. “For the people he paints wear their noses in the usual place, and the weathered barns and bare-limbed trees in his starkly simple landscapes are more real than reality.”

Wyeth’s conservatism is subtle, but that is the source of its power. In a comparison of Wyeth and Kinkade published in The Imaginative Conservative, author and critic Dwight Longenecker praised Wyeth’s unflinching eye for the harsh and heroic realities in American life as “authentic conservatism, in stark contrast with Kinkade’s “Christian kitsch” that “communicates everything that is bogus and stereotypical about American conservatism.”

Of those four conservative artists, I’m betting only Wyeth will still be selling in a hundred years’ time.

There is no small irony in the fact that apart from American conservatives, the other great champions of artistic hyper-realism in the 20th century were the Communist dictatorships of China and the Soviet Union.

In 1932 “Wise Leader and Dear Teacher” Josef Stalin met with favoured Soviet intelligentsia at novelist Maxim Gorky’s apartment. The goal of the gathering was to define socialist art. Characteristically, Stalin settled the matter: “To depict our life correctly, he [the artist] cannot fail to observe and point out what is leading towards socialism. So this will be socialist art. It will be Socialist Realism.”

Naturally, those present instantly recognized this for the towering insight that it was: Socialist Realism would inspire the masses by merging party and ideology with adoration of “Mother Russia.” How could it produce anything other than great art? In practice, of course, it produced little more than vast quantities of propaganda and bore witness to the extinction of human creativity in a totalitarian state.

Oh, there were exceptions. The bucolic abundance of Arkady Plastov’s Collective Farm remains warm and inviting decades after it was commissioned to cover up the genocidal reality of collectivization. You can’t lay that kind of guilt on American social realists like Norman Rockwell – or Jon McNaughton today – although no doubt some progressive essayist has argued that Rockwell was Plastov’s equal in burying “the awful truth about American racism, sexism, and imperialism.”

Canada was mostly a spectator, or fencesitter if you prefer, to these great 20th century struggles for the soul of art. It has been argued that some members of the Group of Seven, particularly Tom Thomson, expressed fundamentally conservative ideas through their landscapes of the great white north. But progressives might just as easily claim Thomson et al as proto-environmentalists or indigenous voice-appropriators.

With the vast expansion of the welfare state in the late 20th century, Canadian art and artists were effectively socialized, with Soviet-style consequences for the country’s overall creative output. Billions of tax dollars invested in “culture” has undoubtedly increased the quantity of Canadian art, but most of it reflects the modernist, progressive, avant garde bias of the granting agencies, arts faculties, and bureaucracies that control the money. If there are any Rockwells, McNaughtons, Penleys or Wyeths painting in Canada today, they are likely eking out a living in the online art market, where quality actually matters.

Despite its widely alleged philistinism, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper did little to disrupt the comfortable world of Canada’s subsidized arts cartels. It did, however, erect a couple of monuments in Ottawa that will be snickered at for years by liberals as examples of conservatively-themed art supporting a conservative government narrative.

The first was a monument marking the 2010 centennial of the Royal Canadian Navy. As a historical and military tribute, it was a perfectly conservative artistic initiative. However, the modernist, abstract sculpture overlooking the Ottawa River – a white curved slab topped by a gold ball – left much to the imagination… A sail? The bow of a ship?

At the unveiling, I wondered how many navy veterans would be uncomfortably reminded of an iceberg.

In 2015, the government erected another monument on Parliament Hill, this one marking the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. It was a conservative artistic trifecta; historical, military and realistic. It supported the government’s Defence of Canada narrative, by featuring the united struggle of anglophone, francophone, aboriginal, and female Canadians. (And the monument’s cannon pointed south…)

It is unlikely however, that these monuments will long be acknowledged as exclusively conservative art. Like the magnificent War Memorial nearby, they evoke national themes and patriotic sentiments in the hearts of Canadians of all political persuasions.

Canada’s preference for the realist style, in most of its Ottawa monuments, is ironic. Aesthetically at least, it suggests we have a greater kinship with the Russians and their Socialist Realist tradition, perhaps best exemplified by the St. Petersburg memorial to the defence of Leningrad, than with our American allies.

After all, the Americans chose to commemorate 9-11 with a modernist installation. The Israelis too, went the abstract route with their Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Tel Aviv.

But so what? Art is a barometer of cultural change. The creative travesty of one century often becomes the precious heritage of the next. As the old leftie playwright George Bernard Shaw said, “All great truths begin as blasphemies.”

Thus, when his opera Tannhauser opened in 1845, Richard Wagner appealed to a nascent but fervent German nationalism. In a time of undemocratic monarchies within Europe, this was a hugely controversial and revolutionary statement. Indeed, in a letter to his friend Franz Liszt, Wagner confessed to “an enormous desire to commit acts of artistic terrorism.”

Given their history, Germans are understandably cautious about radicalism: Many conservatives would agree that all great human tragedies begin as blasphemies.

So, 160 years later, it’s a very unrevolutionary crowd that attends Wagner operas at the annual festival he founded in the Bavarian town of Bayreuth. And in 2014, the festival’s music director Jonathan Meese was fired for his challenging use of political, social and sexual imagery: This, in a genre where incest is at the core of one of its foundational works.

As for Shaw, his socialist blasphemies of a hundred years ago have also been absorbed into today’s orthodoxy: How many conservative editors have thundered: “A government with the policy to rob Peter to pay Paul can be assured of the support of Paul,” quite unaware that Shaw said it first. (I know one.)

So maybe conservatives should be a little more broad-minded about what constitutes good art. Must we ban Salvador Dali from our walls because of his youthful dalliance with Communism, his post-war support of Franco, and his surrealist painting? Perhaps, but what I see in works like his Temptation of St. Anthony is a conservative Catholic admonition to resist the temptations of the flesh. Maybe that’s not what he intended but what the hell, beauty and political intent belong in the eye of the beholder.

The truth then, is that whenever one attempts to constrain conservative art within a narrow ideological compass of artist, subject matter or style, conservatives inevitably do what they want anyway, in pursuit of style, beauty and truth.

For, if conservatism has one great core value, it is freedom: Freedom in trade, in movement, in association, most certainly in speech and artistic expression.

Conservative buyers of art may lean to traditional forms; artists may choose to cater to that taste. But to believe that conservative art reaches its apex when it is indistinguishable from a photograph is to shut out vast opportunities for artistic expression and appreciation.

Is there any art that conservatives can call uniquely their own? Only this: art that is conservative is art that people buy with their own money.

When the Government of Canada decided in 1989 to buy Barnett Newman’s 1967 Voice of Fire painting for the National Gallery at a cost of $1.8 million, there was conservative outrage from coast to coast to coast. To many viewers, the giant canvas composed of three vertical coloured lines looked like the two-bit flag for some island tax haven. The populist conservative Reform Party had a field day attacking Brian Mulroney’s Red Tory Progressive Conservative government for its bad taste and reckless waste of taxpayers’ dollars. And then the National Gallery admitted it had initially hung the painting upside down, thereby proving the expert opinions of some 30 million art critics.

As Olivier Ballou noted in a recent C2C essay, there was a backstory to the painting that should have endeared it to conservatives.

But still. Art that nobody wants to pay for…that can only see the light of day through the agency of state granting agencies and the aesthetes who lobby them…then this art – good or bad, formal or modern – lacks the essential conservative value of free-market exchange.

It might still be art: the Canada Council has swans among its geese. But even the most beautiful bronze of Ronald Reagan shaking hands with Margaret Thatcher, if paid for by taxpayers, could never be classified as conservative art.

Whatever you think of McNaughton’s paint-by-numbers conservative propaganda, it sells. Fox News host Sean Hannity paid six figures for a McNaughton depiction of President Obama burning the U.S. Constitution.

Steven Colbert passed judgement on Hannity’s intellect – if not his artistic taste – by calling him a “televised bag of hammers.” And many “cool” people echo his scoffing.

But the point is, the exercise of choice in art, in a free market, is about as conservative as art gets.

A bit like our modest collection then, of colourful daubs and swatches purchased from a thoroughly capitalist Calgary dealer, with the fruits of our own enterprise.

“Nice conservative art,” we call it. We still don’t have the faintest idea what it’s meant to be. But that’s ok. Because we chose it.