Let us recap recent spring in Canada: governments locked down “their” citizens; police stopped other Canadians at some provincial borders; a few politicians forbade even drive-through church services. The result is a plunging economy paired with soaring government spending, both due to the Corona/Wuhan virus and reactions to the same. We will find out over the next year whether the government-mandated actions were superior to Sweden’s more voluntary model. While the call for social distancing always made sense, government responses to the virus in Canada and abroad mean it is overdue to ask if any fragment of conservatism as generally understood in the postwar world – that economic and individual liberties matter and predate the state – remains anywhere.

This is an especially acute question given that the federal Conservative Party will soon wrap up its leadership race. Its members (I am not one) will choose someone who should serve as a restraint on all the above and more. That person, and it looks to be either Erin O’Toole or Peter MacKay, will oppose the government across the aisle by necessary institutional design as a check on power. The more relevant question, however, is whether a Conservative Party led by either man will offer any alternative to contemporary liberalism, and will do so in a coherent, constructive fashion. Will the party’s new leader and others in the caucus be anchored in something beyond necessary but never-enough schemes to win power, or will the new Conservative leader simply swallow the assumptions of progressivism?

The answer from some corners is that those who favour limited government – whether regarding markets or other spheres of human affairs – should just give up, recognize that we’re not in the 1980s anymore, and that Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher are long dead and so too their ideas, be they economic or otherwise. As the argument goes, new problems require “new” remedies. Thus, as one example, one analyst thinks the way to deal with a tyrannical China is to lessen the importance of free trade and manage Canadian businesses from the top down, with the federal government creating a formal “industrial policy” as it’s called.

To be clear, new problems should indeed be addressed in today’s context. It is one thing, however, to protect an industry from modern-day Chinese espionage, or to avoid off-shoring fighter jet and warship production or government computer programs to a tyranny. It is quite another to continually recommend another version of ever-more political interference in ever-more aspects of the economy, interference which is already legion by any standard, and then to remain, deliberately and as a matter of long-term policy, hyper-Leviathan like governments became this spring.

The call to a new industrial policy is evidence of a fascination with bureaucratic-managerial-political tinkering from above and thus misses two core questions about what a modern conservative party might be.

The latter approach, and the thinking behind it, is not new, although both are touted as such. I have yet to live one month without some public policy group, columnist or government-appointed commission yet regurgitating the cliché arguments for more government-directed managerial interference in the economy, despite decades of failures in various attempts at industrial policy from the 1950s forward, notwithstanding peacetime conditions. Industrial policy has been around since Adam Smith attacked protectionism and mercantilism. It was opposite the public good in the 18th century and remains opposite the public good now. It also has a lot in common with a recent form of liberalism.

The call to a new industrial policy is evidence of a fascination with bureaucratic-managerial-political tinkering from above and thus misses two core questions about what a modern conservative party might be. First, in an always imperfect world, what actually organically works to help protect borders, promote community, deal with tyrants, create jobs and opportunity and lift people out of poverty? Second: Do citizens have rights that precede the existence of governments – natural rights as they are known? The second question is as critical as the first.

Defining and Thinking About Conservatism

Help on both questions comes from the American political philosopher, George F. Will. Will is most famous as a Pulitzer-prize-winning Washington Post columnist but before that wrote for National Review, the standard-bearer of thoughtful American conservatism under its founder, William F. Buckley, and ever since. In his latest book, The Conservative Sensibility, Will tackles the preceding questions in an American context, but any Canadian aware of our own history should welcome the discussion because conservatism, properly understood and defined, is a shared Anglo-American-English Canadian project.

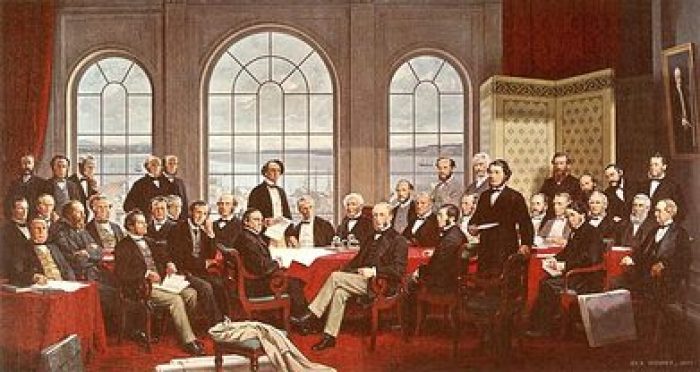

It has been a joint project since English landowners pushed back against King John in 1215 to protect their property rights, which resulted in the Magna Carta and which included the critical core principle that even the monarch was not above the law. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 further entrenched the principle that citizens and not leaders and governments were supreme, as did the 1776 American Revolution, which was a revolt not against the English tradition of limiting the state but a specific rebellion against a tyrannical monarch. Confederation in Canada in 1867 continued this project, as was clear in the thinking and debates which preceded Canadian nationhood. Canada’s founding fathers were concerned with questions of liberty even more so than America’s founders. To use one example, it was why the political leaders of colonial Canada abolished slavery half a century before Americans did.

Conservatives: Defenders of Classical Liberalism

That’s the joint Anglo-American-English Canadian project and one these days referred to in a general sense as conservatism. But it is also and better known by another name: classical liberalism. As Will writes, “America’s politics can be considered a tale of three liberalisms, the first of which, classical liberalism, teaches that the creative arena of human affairs is society, as distinct from government.”

Society for Will and other conservatives is not an institution, which is rather the point. Dating back to Edmund Burke’s thoughts in the late 1700s, this conception of society is that it is not one “thing” but is made up of the organic, everyday voluntary interactions and connections that result in and from family, gathering places like coffeehouses, churches, entrepreneurs, and free-thinking societies, among others. It includes every other imaginable freely-formed “club” whose adherents choose to focus on everything from “minor” amusements such as chess to other-world devotions such as faith, or groups formed for moral or political ends such as to abolish slavery or win suffrage for women.

Will describes two other types of liberalism. The first of these is “middle liberalism”, as he labels it, which is best exemplified by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s over-interference in the economy during the Great Depression. Roosevelt did more than enact a few, necessary and defensible programs for social support which on their own made sense. He supplemented political rights with economic rights, i.e., a “right” to certain economic outcomes as opposed to a more narrowly defined right of opportunity.

A third type of liberalism arose in the 1960s, “managerial liberalism.” This type, notes Will, “celebrates the role of intellectuals and other policy elites in rationalizing society from above, wielding the federal government and ‘science’ of public administration, meaning bureaucracy.” As Will notes elsewhere in The Conservative Sensibility, this third type of liberalism was not new but had its antecedent in the populist progressivism of the early 20th century.

The Illiberal Temptations of Progressives

That today’s third-type liberals once again call themselves progressives is more honest and accurate than using the “liberal” label, given that term once designated those who valued liberty and personal responsibility. Changed labels aside, the core problem with progressivism has always been its assumption of governmental/bureaucratic omniscience and managerial possibilities vis-à-vis the populations such elites rule over – that, and progressives’ belief in the perfectibility of men, women, and their world.

Such a combination tramples liberty in pursuit of some perfectionist end – whatever the flavour of the age happens to be. It explains why, in the early part of the last century, progressives pushed eugenics: a “clean” human race in their utopian (though, in this instance, shockingly immoral) vision did not include “defects” such as those with Down’s syndrome or even those whose behaviour progressives or their families deemed anti-social. The progressives of that era were happy to sterilize both types, and others besides, so that they could not reproduce. Quoting another author on the subject of early progressivism, David Bernstein, Will writes of how “Eugenics attracted progressives because, Bernstein notes, it was congenial to persons committed to ‘anti-individualism, efficiency, scientific expertise, and technocracy.”

Pro-Segregation Progressives

This control-freakish, anti-individual, illiberal approach to men, women and children also showed up in race relations around the same era. As the author points out, while a classical liberal in the era of segregation defended the right of blacks to live wherever they chose, based upon the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of property and liberty of contract, progressives once again deferred to their technocratic, manage-from-above impulse. They did so in the name of societal peace.

Thus, whatever their personal feelings about segregation, progressives defended restrictive real estate covenants that barred blacks from “white” neighbourhoods. As Will writes, “Progressives were committed to the principle of broad deference to a government’s definition of the collective good.” Problem: at the time, the government’s definition of the collective good favoured neighbourhood peace at nearly any price over individual liberties that might upset racists. Real estate covenants which segregated neighbourhoods, for example, were “justified as necessary for reducing racial friction, reducing the spread of communicable diseases, and protecting property values.”

At the core of the progressive assumption is not merely the hiring of a civil servant to process relief cheques during the Great Depression or now during a pandemic, but something invasive and limiting. Progressives’ faith in the manipulation of people has its origins in their preference for the “nurture” side of the “nurture or nature” question.

In other words, progressives sought to justify trampling the life, liberty and happiness of individual black Americans on the grounds of ostensibly greater, i.e., white majoritarian, societal peace. This was easier than to arrest belligerent, racist and sometimes murderous whites because the critical project for progressives was to manage such tensions from above rather than to protect individual liberties, which would have required more bravery and blood.

For a counter-example that preceded the progressive era (an example of actual liberalism), see Abraham Lincoln, who was willing to split the Republic asunder rather than give in any longer to the illiberals who trafficked in human flesh.

Liberty Matters and So Too Human Nature

At the core of the progressive assumption is not merely the hiring of a civil servant to process relief cheques during the Great Depression or now during a pandemic, but something invasive and limiting. Progressives’ faith in the manipulation of people has its origins in their preference for the “nurture” side of the “nurture or nature” question. As Will notes, “To the question, ‘What most determines the trajectory of individuals, nature or nurture?’ the progressives’ answer is that nature is negligible, or can be rendered so.”

Progressives are so attached to this belief that well-articulated evidence to the contrary unnerves them. In a Canadian context, an illuminating example was their reaction to the Jordan Peterson phenomenon. Peterson pointed out that for the vast majority of men and women, significant biological differences exist, which can lead to different choices. For example, Nordic European mothers still on average choose family and relationships over a drive to the executive suite, despite generous childcare policies that would help facilitate the latter choice. All Peterson did was point out that biology – human nature – matters, and can be observed in outcomes.

Will has throughout his career demonstrated that he cares for individual liberties and personal responsibility, and paying attention to nature matters because that combination and not managerial progressivism is what protects people. It is why, for example, the atheist Will defends religious freedom including distinct and often contrarian moral codes to be practised and preached. What matters is the protection of the minority’s liberties – blacks a century ago, religious minorities now, be they evangelical Christians or Muslims – and not the majority’s position when it infringes upon the same.

On economic realities, it is why, during the Cold War, Will consistently pointed out that it was anti-nature and anti-reality to organize a country’s economy on a command-and-control model. No regime can possibly predict the choices and behaviour of tens of millions of its citizens.

Start with Reality and then Think about Political Positions

The Conservative Sensibility is 600 pages and not a beach read. The American author covers everything from the legacy of Princeton University graduates (Will is one and the authoritarian progressive, Woodrow Wilson, was Princeton’s president before he presided over the American republic) to the thoughts of John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, the Federalist Papers, early and later constitutional skirmishes in America’s courts, economics, states’ rights, the Great Depression, Aristotle, Plato, and Karl Popper among much else.

Will’s thoughts are useful for Canadians because too often, Canadian small-c conservatives are treated to partisan preferences badly dressed up as political thought. Such analyses should ask whether the Anglo-American-English Canadian tradition of liberty matters. It does on questions of human nature and on the free exchange of goods and services in open markets without governments blunting supply and demand signals, which then destroy pricing signals. They should ask how to preserve such freedoms or, more accurately, how to restore them.

Instead of such reflective thinking, Canadians too often receive purely power-seeking calculations based on some political party’s reflexive, Hobbesian desire to win an election. For good ideas and policies to be implemented, to be sure, elections need to be won. But to be successful in the long-term – to deliver on a political promise – ideas and policies need to be anchored in economic, social, physical and other realities. That’s because reality – human nature, supply and demand, and the like – always “bites back” eventually. Designing a party platform without attention to hard realities is akin to designing a skyscraper without a proper foundation. It is why analysis of the sort which urges politicians to ape me-too progressivism or even quasi-Chinese practices on “running” an economy will end in economic and political failure.

The Lesson for conservative Conservatives: Avoid the Managerial State

Are there specific lessons from The Conservative Sensibility for actual conservatives within a party that bears the name but not necessarily the DNA? A few come to mind.

First, apply the principle of liberty (accompanied by its necessary siblings, opportunity and competition) to your own party. The current Conservative leadership contest is a case in point.

The Conservative Party’s mandarins decided early on in favour of a quick race with high barriers to entry via an early $300,000 entry fee. That combination virtually guaranteed that few who were not existing or former Members of Parliament could run. Only one of four current candidates, Leslyn Lewis, is not a current or former MP. It takes time and money to build profile in a large country with 37 million people. Instead, potential candidates would first need to raise $300,000 and then spend more time finding more money so they could one day reach out to existing party members and somehow find new ones.

This approach was a mistake because it limited both the political “gene pool” of prospective leaders and the leadership race’s potential to strengthen the party by attracting new members. And unless one thinks peak smarts and abilities exist only in 121 Members of Parliament, who amount to 0.0003 percent of the population (equivalent to a small village), the Conservative Party’s manage-from-top instinct has been its own worst enemy. Small wonder the contest has been mostly bereft of ideas or traction with the public at large – at the very time when an opposition party could have offered both, during a pandemic when non-herd thought is needed most.

Second and far more critically, as an aide to future public debates over ideas, crises and even an occasional election, rediscover the history of conservatism, which any thoughtful conservative today should equate with classical liberalism. By this, I mean the history of Edmund Burke and his cautiousness and also the core liberties that conservatives defended for decades and which, post-19th century, are grounded in English thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and crystallized in On Liberty. This also includes a commitment to personal responsibility.

Third, understand that the project of limiting interference from above is a potential vote-getter in an age of both renewed populism and hyper-active governments.

Analysis of the sort which urges politicians to ape me-too progressivism or even quasi-Chinese practices on “running” an economy will end in economic and political failure.

The limited government project has never been an anti-government project. But governments cannot manage everything from above because the attempt is both anti-reality on economic grounds, and illiberal and injurious to human freedom in methods when attempted, and that overreach is exactly what is occurring. If many Canadians now wonder whether governments have overreached in their pandemic orders, they will also soon begin to demand that some sense of proportion be restored on matters of individual freedom and matters that will soon affect their pocketbooks – stifling entrepreneurs and governments racking up debt which will drown all now alive in red ink as well as children and grandchildren.

Partisans should grasp that the conservative orientation – cautiousness about such an overreach – is about to revive. Moreover, the other part of conservatism, the conservative project since at least the 1960s, which has its antecedent in 19th century liberalism, is also about to become more relevant again: protecting liberties from modern liberals and progressives who are not only anti-reality when it comes to human nature but damage the natural freedoms necessary for a free and flourishing society. This is especially important in times such as these.

Mark Milke is a columnist and author of six books. His most recent is The Victim Cult: How the culture of blame hurts everyone and wrecks civilizations (C2C Journal’s review is here).