At times it is immigrants coming from societies devoid of freedom and democracy who most readily speak out against threats to free and open exchange. Because they have firsthand experience of living in an Orwellian society, they consider priceless what many native-born Canadians might take for granted. Thanks to the superhuman feats of my single mother, I arrived in Canada as an eight-year-old refugee from Iran. I was spared the worst existence under a brutal theocratic regime. Even as a young child, though, I still experienced and heard enough about the fate of family members left behind to make me kiss the soil of this land.

This background helps explain why now, as a lawyer, I cannot help experiencing an allergic reaction any time a subject is deemed taboo: unfit for or beyond public discussion. To me, that is the first indication that discussion must be had. This is even more so when the subject is unusual, novel and one which the courts have yet to fully adjudicate. Transgender rights are one of today’s taboos.

The transgender rights movement has made incredible gains and, as with other civil rights movements, it has forcefully asserted its presence. It now appears, however, that the only acceptable public position is wholesale adoption of all transgender demands. One iota of criticism can unleash the cancel mob. Yet this mob is not comprised exclusively of transgender people; my own experience suggests it is largely an aggressive and socio-economically privileged minority that shouts the loudest and patronizingly purports to speak on behalf of all transgender people.

I was the object of such wrath from members of my profession when I raised a flag on what I believe to be problems with a recently unveiled new policy in B.C.’s courts. It requires every person who comes before the Provincial or Supreme Court to announce their preferred gender pronouns at the beginning of every proceeding. This issue is not primarily about transgender rights. It is about the courts flirting dangerously close to compelling certain forms of speech from those who come before them. Compelled speech forces a person to say certain things, including things they may not believe. It is, therefore, even worse than restricting speech.

While I took the new preferred pronoun policy to be well-intentioned, I saw it as headed on a collision course with other established rights of parties and witnesses in civil and criminal proceedings. In January, I wrote an essay on the subject, which was accepted for online publication by Canadian Lawyer magazine. Within barely three days of its February 5, 2021 publication, it was taken down from the magazine’s site after something under 200 lawyers – out of the more than 130,000 licensed lawyers in Canada – as well as a number of law students and paralegals signed a letter alleging that my article was “legally inaccurate” and “deeply harmful” to transgender people. “We refuse to be pulled into a debate about the worth of trans and non-binary lives,” the letter reads. “The human rights of our colleagues are not something that should be debated. Put simply, this is not a ‘two-sides’ issue.”

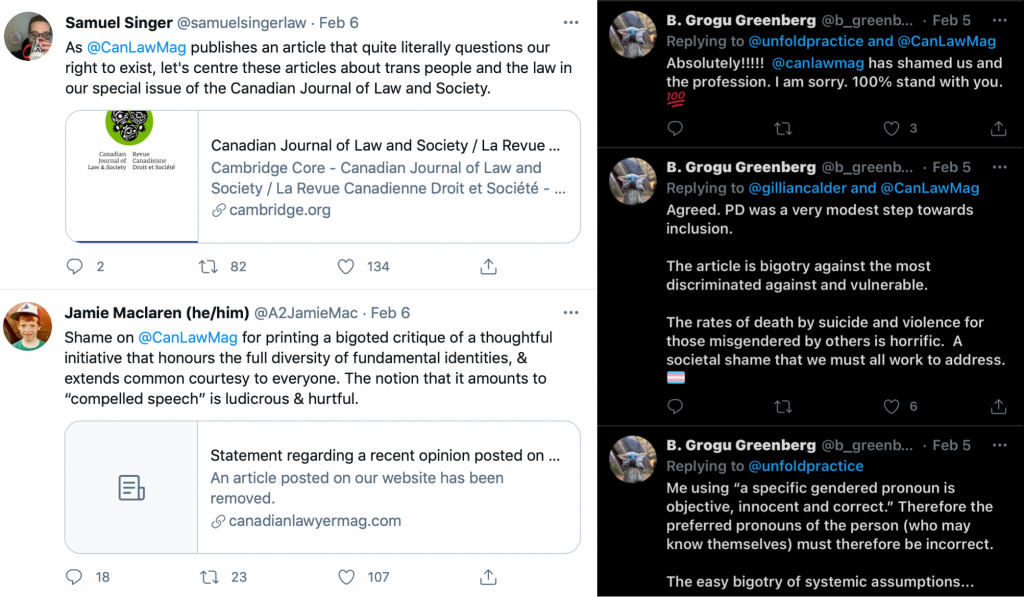

Among the letter’s signatories were three elected benchers of the Law Society of B.C.: Jamie MacLaren, Q.C., Brook Greenberg, Q.C., and Kevin Westell. MacLaren and Greenberg also disparaged me on social media; two of their tweets are reproduced in the adjoining space. (MacLaren later graciously downgraded his description of me as “hate-fuelled” to merely “bigoted.”)

Another tweet alleged that I was literally questioning trans individuals’ right to exist. My favourite tweet, however, was one from a condo lawyer in Ontario – because it clearly addressed the substance of my piece.

My esteemed fellow lawyers who signed the letter skipped the heavy lifting of rebutting my piece with legal analysis of their own, instead choosing name-calling, calumny and hyperbole. But while their voices seemed to represent the totality of legal opinion, this was not the case. I received dozens of private emails of support from lawyers and laypersons across the country and internationally. These notes will never see the light of day, however, because I will maintain their privacy. I can say that there was not a single hateful email.

In a happy irony, my article’s cancellation spurred coverage by print, broadcast and social media addressing my concerns with the policy, including by the Andrew Lawton Show, the Jamil Jivani Show, a National Post column and a Corriere column. The court of public opinion showed there still was much to debate.

Lawyers routinely debate and litigate the most controversial legal issues, such as abortion and euthanasia. Yet the brand-new issue of mandatory gender pronouns in court is to be off-limits before it is debated at all? I beg to differ. Transgender rights activists are entitled to advocate and pursue their interests, just like any other group. I would expect nothing less in a free and democratic society.

By the same token, no one group should claim that their beliefs are beyond challenge or debate. In a free and democratic society, everyone without exception has the right to criticize, dispute and reject whatever they may disagree with. Any pluralist society will always have to grapple with competing rights, interests and values. The legislatures and the courts must ultimately strike the balance, after considering full argument. Doing so in a fully informed way requires a full, open and reasoned debate free of calumny or the threat of retaliation. In my opinion, the B.C. Provincial and Supreme courts have failed to strike the balance and protect critical rights in their new policy mandating the use of preferred pronouns.

New Practice Directions from the British Columbia Supreme and Provincial Courts

On December 16, 2020, the B.C. Supreme and Provincial courts each issued new court directives, almost identical in wording. The Supreme Court’s version (PD 59) reads as follows:

This Practice Direction clarifies how parties and/or counsel can advise the Court, other parties, and counsel of their pronouns and form of address.

- At the beginning of any in-person or virtual proceeding when parties or counsel are introducing themselves, their client, a witness, or another person, they should provide the judge or justice with each person’s name, title (e.g., “Mr./Ms./Mx./Counsel Jones”) and the correct pronouns to be used in the proceeding.

- If a party or counsel do not provide this information in their introduction, they will be prompted by a court clerk to provide this information.

(Emphasis added.)

As reported in news releases, the directions from the Provincial and Supreme courts are principally aimed at making non-gender-conforming participants feel more comfortable in court by making everyone give their correct pronouns. But parties and lawyers were already free to make these assertions voluntarily known to the court at any time during proceedings. And in contrast to the mandatory nature of these new directions, the B.C. Court of Appeal in October 2019 had issued voluntary guidelines that simply ask parties to a court proceeding to “advise” the clerk of their name and their “preferred manner of address,” while remaining silent on pronouns, let alone “correct” pronouns that everyone must use.

No one group should claim that their beliefs are beyond challenge or debate. In a free and democratic society, everyone without exception has the right to criticize, dispute and reject whatever they may disagree with.

The directions from B.C.’s Provincial and Supreme courts were issued following guidance provided by the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Community (SOGIC) Section of the Canadian Bar Association’s B.C. chapter. The courts do not appear to have consulted with any other group of lawyers or members of the public. As its name suggests, SOGIC is overtly progressive in ideology and has declared its next lobbying issue to be gender-neutral courthouse bathrooms and barristers’ change rooms, and eradication of the gendered titles “My Lord” and “My Lady” for Supreme Court and Court of Appeal judges.

According to at least two recent media accounts of the new practice directions (available here and here), it is clear that the term “correct pronouns” actually refers to what are commonly called preferred gender pronouns. They express a subjective gender identity which may or may not accord with that person’s biological sex and which may not be permanent, in some instances evolving over time or even changing repeatedly for those who identify as non-binary or gender-fluid.

Adherents of subjective gender identity generally favour the eradication or at least the diminishment of the use of biological sex as the marker of gender division in society, in language and in sex-segregated spaces. They strive to uphold gender identity based on self-identification and self-declaration. Any reference to one’s biology is deemed to be insulting or worse. This view has gained traction in Western countries, but it is far from settled. The legal battles between gender identity and biological sex have been and continue to appear before Canadian courts and human rights tribunals on a variety of fronts; see, for example, here and here.

In short, the B.C. courts’ new practice directions are controversial. They will instigate clashes with long-established rights of parties and witnesses to give evidence in their own words, and with lawyers’ professional and ethical duties. Further, compelling an answer to the “pronoun question” is intrusive and can amount to a breach of privacy in substance if not in law. Finally, by transforming the contentious and sensitive issue of preferred pronouns into official policy, B.C.’s courts have signalled that they have taken a side in a larger socio-political debate between gender identity and biological sex. This damages the optics, if not the substance, of judicial impartiality and independence.

Compelled Speech

The B.C.’s courts new directions are not “law” as ordinarily understood, but they are an instruction from the court that must be followed under its inherent power to control its own processes. Litigants and practitioners are expected to comply with all court directions. Assuming the court clerk asks the “pronoun question” at the start of every proceeding, an answer must be given. The directions also imply that when someone has self-declared their pronouns, voluntarily or otherwise, other court participants must use those pronouns when speaking in the third person during the giving of evidence or conversations in court, and presumably in court documents as well. If these directions are put into practice consistently and enforced, it is difficult to describe the result as anything but compelled speech.

Some might argue that this is a non-issue because it is already settled via provincial human rights codes. Indeed, outside of court, these laws expressly protect against discrimination on gender identity and expression in prescribed contexts, namely publications, employment opportunities, tenancy agreements and the provision of public services, among other specified contexts. For example, if someone provides wedding photography to the public, they will very likely be unable to deny the service to a potential customer by relying on their religious freedom enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

None of the prescribed contexts of discrimination set out in provincial human rights codes specifically extend to in-court proceedings. Individuals come before the court in an adversarial context, and they must remain free to maintain untrammelled discretion on how they prosecute or defend their case, or express themselves as witnesses. A pronoun violation in court should not equate to an actionable act of discrimination pursuant to provincial human rights laws.

Failing to follow the new practice directions will likely be viewed by at least some judges as disrespectful or as improper conduct, and be punished accordingly using the impressive sanctions related to contempt of court. The problem remains, however, that other parties and witnesses still have rights of expression, conscience and religion based in the Charter. Who is to prevail? Does the individual with the preferred pronoun get the veto every time? And when a practice direction might be said to infringe on Charter rights, who would adjudicate any claim that they do? Why, the same courts.

Another issue is that lawyers must adhere to professional codes of conduct that require civility whether inside or outside the courtroom. Given the new directions, lawyers may be placed in a conflicted position wherein they are caught between adherence to professional codes of civility and their duties to their client and their legal position.

The examples below elucidate these legal conundrums.

Bad Conduct or Attestant’s Rights?

My critics have accused me of overblowing the threat posed by the new practice directions. They insist that the key provision doesn’t amount to compelled speech, and that nothing bad will come of it – only the benefits of recognizing differently-gendered people and making them feel comfortable in court.

A recent case in the UK, however, painfully demonstrates the potential for improper judicial intervention based on remarkably similar provisions to B.C.’s new court directions. The UK’s Judicial College, which trains the judiciary in England and Wales, publishes an Equal Treatment Bench Book whose introduction includes “guidance” suggesting that judges use preferred pronouns to show respect for gender identity.

In 2018 Maria MacLachlan, 61, was assaulted during a demonstration in a public park in Central London by a 26-year-old who on surveillance video appeared to be a male. When MacLachlan gave evidence at trial, the judge said that the “defendant wished to be referred to as a woman, so perhaps you could refer to her as ‘she’ for the purpose of the proceedings.” MacLachlan replied, “I’m used to thinking of this person who is a male as male.” MacLachlan said that she tried to comply with the judge’s instruction during the trial, but out of nervousness kept referring to the defendant as “he.”

The accused was convicted of assault and ordered to pay a fine of £150. The judge is reported to have described MacLachlan’s inability to use her assailant’s preferred pronouns as “bad grace.” This, in turn, reportedly became one of the reasons the judge withheld financial compensation from her.

In short, the victim of a physical assault was effectively punished by denial of rightful legal compensation because she struggled to show coerced “courtesy” to her assailant based on “guidance” that allegedly has no force of law. The court attempted to compel a witness to describe her evidence under oath in a way that was not her evidence. The court’s imposition of pronouns also obscured reality, since the assailant’s identity was implicated on video and because the gravity of the assault mattered. MacLachlan’s evidence was that she was assaulted by a grown biological male rather than a biological female, and the more serious the assault, the stiffer should be the penalty.

The Canadian context could well be different, but my concern remains the same: Who gets the veto over the speech used in our courts, and when? What if the party on the stand is, like MacLachlan, confused and upset? What if the person is a deeply religious individual and refuses the preferred pronouns based on grounds of conscience? What if they decline a particular preferred pronoun simply because they believe it doesn’t reflect the truth? There is no clear answer on when one right will trump the other. But to say that all rights are equally important in every context in which those rights are triggered is legally incorrect and simply not true when you look at how the legal system must grapple with conflicting rights on a daily basis.

The directions from B.C.’s Provincial and Supreme courts were issued following guidance provided by the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Community (SOGIC) Section of the Canadian Bar Association’s B.C. chapter. The courts do not appear to have consulted with any other group of lawyers or members of the public.

Ultimately, the decision on whether a preferred pronoun will be employed ought to rest with the attestant – that is to say, the person giving evidence under oath. That is not discrimination nor bigotry. Just because an attestant declines to use a preferred pronoun for a trans or binary person does not mean that person ceases to exist. Their existence cannot rise or fall based on how they are referred to in the third person in court when an attestant is giving their evidence under oath. Needless to say, the court’s priority in fashioning court directions should be to serve the purposes of truth-seeking, justice and procedural fairness for all parties, rather than providing emotional comfort to individuals.

Some of my critics have also attempted to rebut my original article by noting that there is already a form of compelled speech when we address the court with honorific titles such as “Your Honour,” “My Lady” or “My Lord.” But these instances are immaterial to the case at hand, and are used by all equally to signal everyone’s recognition of the court’s authority and legitimacy. In any case, some lawyers already refuse to use “My Lord” and are not sanctioned.

Threat to Lawyer’s Duty

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has held that the duty of resolute advocacy requires lawyers to stand strong in the face of harsh criticism from the public or the bar, and even the disapproval of the court, when advocating on their clients’ behalf. Nevertheless, the SCC does not advocate incivility. When assessing whether a lawyer’s behaviour warrants punishment by the law society for misconduct in court, care must be taken to set a sufficiently high threshold that will not chill the kind of fearless advocacy that is at times necessary to advance a client’s cause.

It follows that a lawyer ought never to be under any obligation to amend their language when doing so would go against their client’s legal position or instructions. Personally, I would have no problem using another lawyer’s preferred pronoun, nor that of their client, nor certainly that of my own client. If my client had a preferred pronoun, I would also request that everyone else respect their wishes. Voluntary courtesy is entirely different from coercing people to endorse a belief system that they may not agree with.

Asking the attestant to use a gender-neutral pronoun such as “the accused” or “the plaintiff/defendant” is a good idea when the issue of gender has nothing to do with the legal matters at play. In such instances, it amounts to a courtesy that does no harm. But it still must not be forced upon a witness, requiring them to mince their words, as that comes dangerously close to eroding their right to give evidence freely. In some instances, the issue of gender is material or even central to the case itself. In such instances, forcing a lawyer or witness to use a gender-neutral alternative may run counter to their legal strategy, position or the litigant’s very cause of action.

The accused was convicted of assault and ordered to pay a fine of £150. The judge is reported to have described the victim’s inability to use her assailant’s preferred pronouns as “bad grace”. This, in turn, reportedly became one of the reasons the judge withheld financial compensation from her.

The intersection between a lawyer’s professional duty to maintain courtesy, respect and decorum, and their duty of loyalty to their client’s cause may unfortunately conflict. The duties can clash in the same word – that personal pronoun. GivenSCC jurisprudence, it is well established that my duty, as a lawyer, to my client’s cause is paramount. I would prioritize that over affirming another’s subjective gender identity out of courtesy and respect, if there was a conflict between the two.

Even before the new court directions, the issue of obligatory preferred pronouns arose on a few occasions before the B.C. Supreme and Appeal courts. In A.M. v Dr. F, 2021 BCSC 32, a mother unsuccessfully tried to stop her 17-year-old child from having a double mastectomy in connection with the minor’s desire to transition to the masculine gender. During the proceeding, the minor’s lawyer requested that the minor be referred to using male pronouns. The presiding judge asked counsel for the mother whether he refused to respect the minor’s request.

The lawyer for the mother, Carey Linde, clarified that he meant no disrespect to the minor, but in the courtroom he was obliged to uphold his client’s position that she still had a daughter rather than a son. To do otherwise would force the mother to repeatedly affirm and normalize the position of her adversary, here the minor – the very issue that had brought her before the court. She wanted to keep having a daughter as opposed to a son. The mother did not testify in that case, although if she had, I suspect she would for the same reasons have also declined to use the minor’s preferred pronoun.

If a judge asks a lawyer, party or witness to use another’s preferred pronouns, the lawyer or litigant could easily see such request as a binding court order, to be obeyed fully and immediately, leading to fear of being in contempt of court or (for a lawyer) being hauled before the law society for conduct unbecoming a member. That would be bad enough. But what happens if a judge, in turn, misconstrues the common use of pronouns based on biological sex (and, in this case, the formal legal position of the mother) as malice, disrespect or insult? Neither a contempt of court charge nor a law society complaint by the other party’s lawyer is far-fetched. In any of these instances, one party’s ability to advance its case would be undermined.

One may ask why the mother and lawyer could simply not use a gender-neutral noun like “minor.” The answer is that their litigation strategy included repeatedly affirming the mother’s position that she has a daughter. Forcing the mother or her lawyer to use another word would stymy their advocacy of their case as they saw fit. Likewise, opposing counsel would never use the word “minor” as that would go against their strategy to affirm their client’s right to decide on this surgery on her own, without parental permission. Ultimately in A.M. v Dr. F, neither the mother nor her lawyer were penalized for referring to the minor with female pronouns in the court hearing.

If a judge asks a lawyer, party or witness to use another’s preferred pronouns, the lawyer or litigant could easily see such request as a binding court order, to be obeyed fully and immediately, leading to fear of being in contempt of court or (for a lawyer) being hauled before the law society for conduct unbecoming a member.

But the courts do not always practice such a “light” touch. Even before the recent practice directions, gender-dysphoric minors had applied to court for, among other things, orders compelling their parents to use the minors’ preferred pronouns when communicating with their child. In A.B. v C.D., 2020 BCCA 11, the court ordered the father to “acknowledge and refer to AB as male and employ male pronouns, both generally and with respect to any matters arising in these proceedings.” (The father was also subject to a publication ban and anonymity orders, and was recently imprisoned for breaching these as he sought to draw attention to the medical treatment of transgender minors.)

The court order on the father’s use of pronouns in A.B. v. C.D.was rooted in a section of the Family Law Act of B.C., called “conduct orders.” In this case, the order’s wording seemed to suggest that it applied tothein-court hearingin addition to outside of court. Applying the order this way was legally incorrect, in my view. In any event, it prejudiced the father in crafting his defence. It is unclear whether the conduct order also applied to the father’s counsel in court. If it did, it would have been a devastating infringement upon the lawyer’s duty to his client’s cause. This case ought to have been appealed.

Breach of Privacy Rights

The directives may, ironically, also have deleterious effects on those whom they are intended to help: transgender individuals, including people who are uncertain of, or struggling with, their gender identity. Not everyone wishes to have their pronouns – and thus their gender identity – announced in public. Asking for preferred pronouns that have not already been volunteered is akin to “outing” someone, and could occur against the person’s will.

Answering the question could also reveal something of their personal beliefs about themselves and, indirectly perhaps, their sexual orientation. Despite limitations on privacy rights in open court, it would seem prudent to avoid unjustified overreach into personal and sensitive details. The question of one’s gender identity is and ought to remain irrelevant to a court’s proceedings unless it is actually an issue in the litigation, in which case evidence and testimony will be presented.

Judicial Impartiality

The new court directions inadvertently damage the optics of judicial impartiality. The concern was eloquently put by Judge Stuart Kyle Duncan in United States of America vs. Varner, Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, January 15, 2020. In that case, a federal prisoner’s appeal included, among other things, a motion that the court refer to him using female pronouns, in person and in court documents. The court declined the request, and these were among its reasons:

“…If a court were to compel the use of particular pronouns at the invitation of litigants, it could raise delicate questions about judicial impartiality…Increasingly, federal courts today are asked to decide cases that turn on hotly-debated issues of sex and gender identity. [citations omitted] In cases like these, a court may have the most benign motives in honoring a party’s request to be addressed with pronouns matching his ‘deeply felt, inherent sense of [his] gender.’ [citations omitted] Yet in doing so, the court may unintentionally convey its tacit approval of the litigant’s underlying legal position. [citations omitted]. Even this appearance of bias, whether real or not, should be avoided.”

As we have seen, even prior to B.C.’s new court directions, minors in gender dysphoria cases were seeking court orders forcing their parents to use their preferred pronouns at all times, whether inside or outside the courtroom – even in the home. Parents fought against such orders without much success. Were such a request made now, can anyone honestly believe the parent would stand a fighting chance?

Conclusion

In order to adhere to their judicial oath, judges must be wholly independent. Individual judges are masters of their own courtrooms. Any hint that the courts are institutionally aligned or champion the interests of a particular civil rights movement can weaken the public’s perception that the courts are free from persuasion and influence by any special interest group. With the recent practice directions, the Honourable Chief Justice of the B.C. Supreme Court and Chief Judge of the B.C. Provincial Court have arguably told other independent judges how to conduct themselves in their own courtrooms, on an issue of public controversy that is far from settled or resolved.

By requiring all participants in court proceedings to state their pronouns, the courts of B.C. are affirming pronouns as identity markers of importance to every individual – regardless of whether the individuals concerned share this view. The new practice directions implicitly require each court participant to accept the position of gender activists that prioritizes subjective gender identity over biological identity. This remains a hotly debated issue in Canadian society, which the courts would be well advised to steer clear of.

No matter how well-meaning B.C.’s new directives might be, they present a dangerous flirtation with compelled speech in open court, risking privacy breaches, and exposing themselves to accusations of favouring one side in intense legal and political debates. One can only hope that the courts will think long and hard about the wisdom of this new direction.

Shahdin Farsai is a lawyer practising in Kelowna, B.C.