The evil that men do lives after them. The good is oft interred with their bones.

— William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

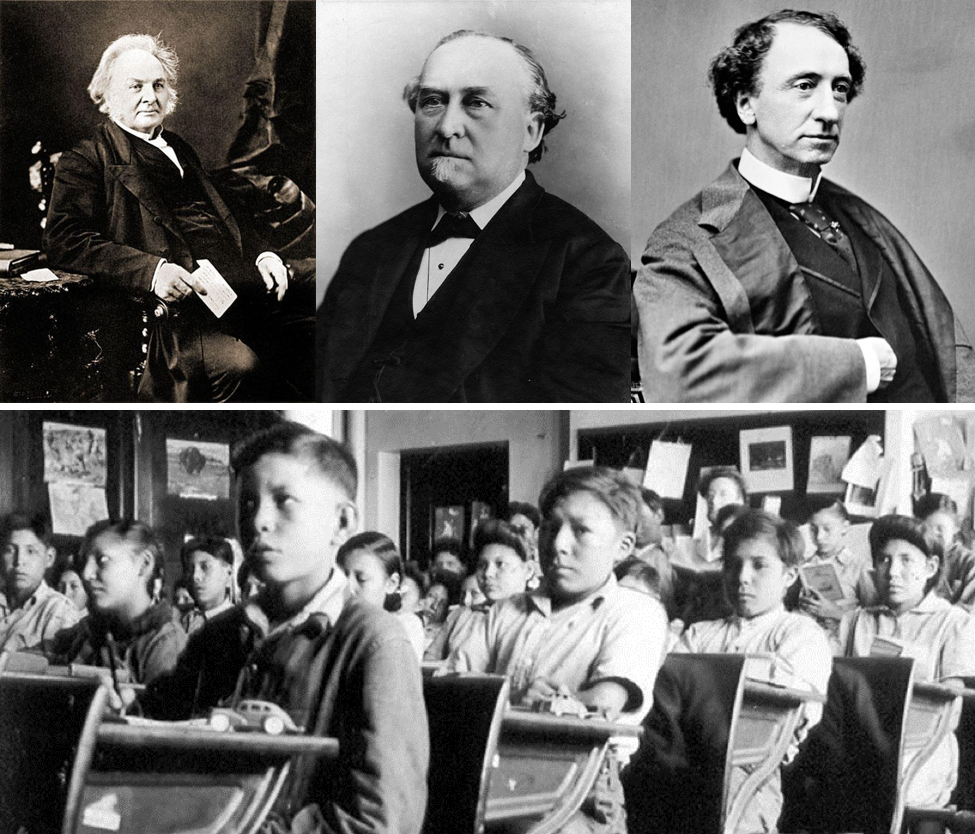

For Canadians with an interest in honest history, Mark Antony’s funeral oration of Julius Caesar set over 2,000 years ago seems truer than ever. Over the past several years many of our country’s most significant past figures have been toppled from their plinths, erased from city maps and struck from public records in a paroxysm of historical cleansing. Among the victims: Sir John A. Macdonald, Egerton Ryerson, Edward Cornwallis, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin, Matthew Baillie Begbie, Samuel de Champlain, General Jeffrey Amherst…the list goes on and on.

Whatever good these dead white men may have done in their lives – particularly their significant roles in creating modern Canada – has today been “interred with their bones.” Any single act or statement at odds with the purported values of contemporary Canada is sufficient to warrant their public condemnation followed by swift obliteration from our recognized past. The crucial test for many concerns an association, however remote or tangential, with Canada’s fraught Indian Residential School system.

Ryerson, for example, was long celebrated as the pioneer of free public schooling in English Canada. Yet a brief he wrote in 1847 offering his thoughts on what a government-run school system for native Canadians might look like – four decades before such a thing came into being – is now considered evidence of his participation in the many failures of residential schools in the 20th century. And reason enough to remove his name from Ryerson University in Toronto.

Similarly, Langevin was a key figure in French/English relations during the period leading to Confederation and in the new Dominion’s early years. As federal Minister of Public Works he was responsible for the construction of many residential schools, although not the underlying policy that animated them. Regardless, in 2017 Langevin was judged connected to the schools and his name quickly vaporized from one of Parliament Hill’s most significant public buildings.

Then there is Macdonald, once regarded as Canada’s greatest statesman and founder of our country. Today, he is described in the darkest possible terms: a purveyor of genocide and plotter of assimilation. Again, the case against him typically centres on residential schools and their now-discredited policy of mandatory attendance. This despite the fact mandatory attendance was not introduced until 1920, 27 years after his death, and was ever only half-heartedly enforced. Plus, Macdonald was a tireless and progressive supporter of Indigenous rights and wellbeing, as is amply documented by his historical record. But none of that matters. A single deed or word is now reason enough for cancellation.

Amidst all the current laments over colonialism and white supremacy, however, there is one dead white male from the previous century whose reputational trajectory has moved in the opposite direction. As the memories of his many peers lie in disgrace and tatters, that of Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, a senior public health official at the turn of the 20th century and heretofore a minor character in Canada’s historical record, is rising triumphant.

A New Hero for Our Times

Bryce today is widely feted as a “hero” for his efforts to improve residential schools. In 1907, as chief medical officer of health for the Department of Indian Affairs, he investigated the dismal health conditions at these schools in western Canada and issued an official report that received considerable public and political attention. Later, he tangled over further reforms with Duncan Campbell Scott, the imperious bureaucrat who ran Indian Affairs for several decades and is now widely regarded as a racist. Bryce was eventually sidelined in this struggle.

A mailbox Blackstock installed beside Bryce’s headstone has become a repository for fan mail from other present-day admirers. ‘Thank you for your courage and care,’ someone recently wrote to Bryce, who died in 1932. ‘You had great courage and spoke the truth,’ said another.

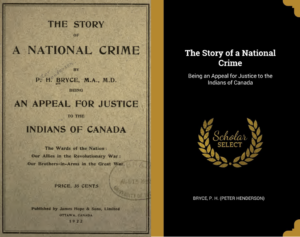

After retiring, however, he self-published the pamphlet The Story of a National Crime: An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada in 1922 in an attempt to bring renewed attention to the matter. For this, Bryce is now celebrated as an early “whistleblower.” It is a renaissance that has been driven largely by Indigenous scholars and activists.

Cindy Blackstock, a much-quoted Indigenous professor at McGill University, recently wrote in the Canadian Medical Association Journal that Bryce “stands as a hallmark of…moral conviction and courage.” Blackstock, who is also the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and a key figure in litigation over the federal government’s treatment of native children in the modern welfare system, presents herself as a relentless critic of Canadian Indigenous policy. Yet she appears to have adopted Bryce as something akin to a saviour figure.

Blackstock organized a well-publicized refurbishment of Bryce’s grave site in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery in 2015 and says she leaves spiritual offerings when she visits. She also claims to read aloud excerpts from recent court rulings at his graveside, presumably as a way of communing with his spirit. And a mailbox Blackstock installed beside Bryce’s headstone has become a repository for fan mail from other present-day admirers. “Thank you for your courage and care,” someone recently wrote to Bryce, who died in 1932. “You had great courage and spoke the truth,” said another.

A transcendental mailbox is not the only example of Bryce’s new-found celebrity. Three scholars, two of whom are Indigenous, wrote a lengthy paean to Bryce in The Globe and Mail this past summer. “Bryce’s work fell on refusing ears,” they explained. “We should listen to him now.” Yet another Indigenous scholar, Pam Palmater of Ryerson University, well-known for her acerbic views of white Canada, is equally laudatory of Bryce in the academic journal Aboriginal Policy Studies. “In the early 1900s, Dr. Peter Bryce exposed the genocidal practices of government-sanctioned residential schools, where healthy Indigenous children were purposefully exposed to children infected with tuberculosis, spreading the disease through the school population,” she wrote last year. (Her claims are untrue, but that seems beside the point.) The long-dead Bryce even makes regular appearances on social media; his picture was recently featured on CBC’s Instagram feed with the caption, “He tried to raise the alarm about residential school conditions in the early 1900s.”

To cap off Bryce’s remarkable rebirth, the historical organization Defining Moments Canada next year plans a national commemoration of Bryce’s 1922 pamphlet, now hailed as “The Bryce Report.” to mark its 100th anniversary. This slim 20-page volume, out of print for nearly a century, is available on Amazon for $24.50.

Bryce’s reputation has thus achieved a level of veneration and respect no other white Anglo-Saxon Protestant male from Canada’s distant past has reached in recent memory. That this elevation is almost entirely due to the efforts of Indigenous scholars and activists makes his ascent all the more remarkable. Such a curious state of affairs deserves a closer look. Can the facts of Bryce’s life sustain his current level of adoration? Can anyone’s?

The Man and His Times

Bryce was born in 1853 into a prosperous Presbyterian family in Mount Pleasant, a small town west of Hamilton, Ontario. He attended the University of Toronto where, among other degrees, he acquired a Bachelor of Medicine. He received several medals for exceptional achievement and in 1880 opened a medical practice in Guelph, Ontario. Two years later, Bryce received a political patronage appointment as secretary of the Ontario Board of Health and was later appointed deputy registrar of vital statistics. As such, Bryce frequently found himself at the forefront of the burgeoning field of public health.

Through most of the 1800s, deadly diseases such as typhoid, cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis (TB) and diphtheria wreaked havoc on urban populations around the world. These health threats were for centuries widely assumed to be caused by “miasma,” or bad air arising from decaying organic matter. Individuals were thought to be sickened by their environment rather than contact with infected individuals. Only after the pioneering work of scientists such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch was belief in miasma supplanted by germ theory, and the understanding that these diseases were spread by tiny particles of living matter through person-to-person contact.

As part of his provincial duties, Bryce was highly visible in promoting health-related measures, including the need for better municipal garbage, sewage and water treatment. And he showed decisive leadership when necessary. In 1895 he sought to quell a typhoid outbreak by ordering the closure of all private wells in the southwest Ontario city of Brantford and the provision of free water to those affected.

Bryce was also an early advocate of statistics as a tool for improving public health and was involved in the collection and tabulation of data on causes of death and disease outbreaks. In 1900, thanks to his rising reputation, he became the first Canadian appointed as president of the American Public Health Association.

Judging by his many appearances in the contemporary press, Bryce was also a stereotypical Victorian gentleman with wide-ranging, if somewhat idiosyncratic, interests and a strong desire for public attention. In 1882 he gave a lecture on hypnotism at the Canadian Institute and noted the technique’s particular effectiveness on “emotional persons and oftener in the female sex than in the male.” In 1897, speaking to the Women’s League about TB, he argued for the “total demolition” of infected houses. (We now know that many common disinfectants, including vinegar, effectively kill the tuberculosis bacterium, making demolition unnecessary.)

Bryce was particularly interested in the link between building design and disease, especially with respect to air flow and natural light. In The Globe in May 1898 he decried the layout of Toronto’s public schools, declaring the “ventilation, lighting, heating, floor and air space allowed each pupil to be totally inadequate.” Given recent experience with Covid-19, such opinions seem rather farsighted. As for his reasons, “The immediate effects of the foul air are to injure the nutrition of the child. The appetite and digestion are disordered, and every tissue and primarily the nervous system is affected,” he explained to Globe readers, mustering more conviction than evidence. Despite his outsized reputation today, Bryce was very much a man of his times.

Dr. Bryce Goes to Ottawa

In 1904 Bryce received another patronage appointment, this time from the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, as chief medical officer for the federal departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs. Bryce had no particular expertise with native issues and his initial duties consisted primarily of compiling an annual statistical report based on input from departmental staff across the country. At a time when health care in Canada was entirely privately funded and delivered, Indian Affairs employed over 200 full- and part-time medical personnel serving Indigenous reserves and schools in fulfilment of federal treaty obligations.

Bryce’s belief that inter-marriage (admixture) and assimilation into white society offered Indigenous people protection from disease and that the Chippewas’ health problems were related to their ‘moral development’ were commonly-held opinions among educated people of his time. Such positions today would obviously be met with outrage and charges of racism.

In his first departmental report in 1905, Bryce was struck by the great variation in death rates between native and non-native Canadians, a situation that set his inquiring, data-focused mind to work. Among non-natives, the reported annual death rate was 15 per thousand, yet on some reserves in western Canada it exceeded 70 per thousand – or 7 percent of the entire Indigenous population every year. For the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte in Ontario, however, the rate was a mere 7 per thousand – half the Canadian average. Clearly some reserves were experiencing terrible health outcomes, while others were not. What was going on?

To gain insight, Bryce compared the Six Nations Mohawks of the Grand River (death rate 18 per thousand) with the nearby Chippewas of Sarnia (52 per thousand). His conclusions, informed by the prevailing attitudes of his era and his own observations, strike a distinctly discordant note today:

“Perhaps there has been a greater admixture of white blood in the Six Nations…the real and essential difference is that the Chippewas have lived much by other work than farming available in Sarnia and on the river, while the lawlessness in the matter of liquor-selling, peculiar to the border, has helped to make the difference. It is primarily a difference in moral development, with its accompanying lagging behind in material advancement, both of which are chief factors in determining the health of any people.”

Bryce’s belief that inter-marriage (admixture) and assimilation into white society offered Indigenous people protection from disease and that the Chippewas’ health problems were related to their “moral development” were commonly-held opinions among educated people of his time. Such positions today would obviously be met with outrage and charges of racism. In his report the following year, Bryce again returned to the theme of assimilation, noting the “invaluable admixture of white blood with its inherited qualities in improving the health of native communities.”

The TB Problem

Bryce’s modern-day elevation by Indigenous scholars rests on setting aside his now-heretical views on native society and instead focusing on his work regarding health conditions in residential schools. While smallpox was initially the greatest threat to Indigenous people during the colonial period, an effective federal inoculation campaign wiped out the disease throughout Canada’s native communities by the turn of the 20th century.

During Bryce’s time, TB had become the predominant killer of Indigenous people. It is a slow-moving and insidious disease; over 90 percent of people infected with TB show no symptoms and are not contagious. Only once their immune system is weakened by another ailment such as a cold or the flu (with poverty a frequent accelerant) does the disease become active and highly contagious. An infected person gradually loses lung function and weight, wasting away over a period of up to a decade. Hence TB’s historical name of “consumption.”

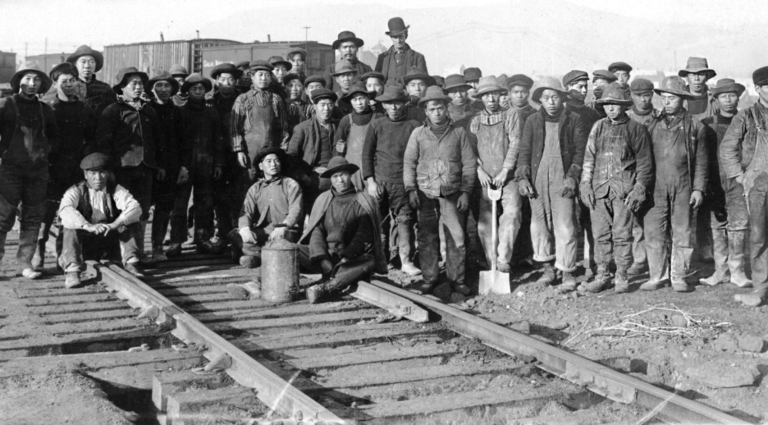

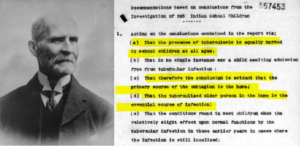

In 1907, amid growing concerns about reported high rates of TB at residential schools, Indian Affairs ordered Bryce to conduct a tour of native boarding schools across western Canada and report on what he found. He visited 35 schools in three months. And while there are several flaws in his statistical methods, Bryce’s observations delivered a devastating indictment of Canada’s residential school system as it operated in 1907.

According to Bryce’s data, of 31 students reported discharged from the File Hills residential school in Saskatchewan, “9 died at school” and another six died thereafter, for an observed mortality rate of nearly 50 percent. Overall, “of a total of 1,537 pupils reported upon, nearly 25 per cent are dead.” What Bryce found was undeniably grim. As for the reason, “everywhere the almost invariable cause of death given is tuberculosis,” he reported. Given that the health condition of most incoming students was recorded as “good,” Bryce reasonably surmised that the schools themselves were a major factor in the disease’s transmission. From his report:

“The defective sanitary condition of many schools, especially in the matter of ventilation have been the foci from which disease, especially tubercular, has spread, whether through direct infection from person to person, or indirectly through the infected dust of floors, school-rooms and dormitories.”

Bryce’s 1907 official report emphasized three areas for improvement: enhanced ventilation and floor space standards, better medical screening of students prior to entry into school and mandatory “calisthenics” (or physical exercise) for all students to bolster their overall health.

The Government’s Response

Bryce’s report was prepared and delivered to his superiors by June 1907, just a month after his return. Bryce’s reputation as a whistleblower partly rests on claims by his current supporters that this report was not formally released by his department due to its critical nature. According to the online entry on Bryce in the Canadian Encyclopedia, “The Department of Indian Affairs did not publish Bryce’s report. It was leaked to journalists, however, prompting calls for reform from across the country.”

The new 1911 school standards are thus directly traceable to Bryce’s three original observations. Despite what his many supporters may claim today, Bryce scored a policy hat trick. The new standards had an immediate and salutary effect on school facilities.

This is inaccurate. As a memo found by the author in the national archives (see page 28) reveals, copies of Bryce’s report were delivered to all Members of Parliament and Senators, as well as senior representatives of all churches involved in operation of native schools and, further, to the principal of every Indian boarding school in the country, with a request for comments.

Bad press: Despite frequent claims that Bryce’s 1907 findings were suppressed or ignored by the federal government, his report actually received widespread public and political attention, as this clipping from the Victoria Daily Colonist of November 16, 1907 attests.

Bad press: Despite frequent claims that Bryce’s 1907 findings were suppressed or ignored by the federal government, his report actually received widespread public and political attention, as this clipping from the Victoria Daily Colonist of November 16, 1907 attests. As for the political fallout, the report was debated in the House of Commons when the Conservative opposition grilled the government on Bryce’s finding of “defective sanitary conditions” at the schools. “The matter is of course one of very grave importance. It has been taken up with the authorities who are in direct charge,” Frank Oliver, the Minister of Indian Affairs, dutifully replied. Bryce’s report was also mentioned in many newspapers, including The Globe and Toronto Star. “The report is significant,” declared the Victoria Daily Coloniston November 16, 1907 under the headline “Indian Schools Deal Out Death.”

Beyond erroneous assertions that Bryce’s report was never publicly released, the surrounding mythology further claims that Ottawa deliberately ignored it, as Blackstock has alleged in an op-ed in Maclean’s.

In truth, Bryce’s 1907 report was handled as minister Oliver promised. Bryce’s troubling findings played a key role in setting the agenda for negotiations the very next year between Ottawa and the various churches operating residential schools. This process culminated with the signing of a new federal funding arrangement in 1911 that tied significant increases in the budget for native schooling to new, tougher building standards for the church-run schools.

The new contract was notable for its specific ventilation and air space requirements, setting the minimum at 500 cubic feet per student in dormitories and 250 cubic feet per student in classrooms. It also directed that no student should be admitted into a residential school “until, where practicable, a physician has reported that a child is in good health.” Finally, all teachers in residential schools were required to use the textbook Calisthenics and Games for “improving and strengthening the physical condition of the boys and girls.” The new 1911 standards are thus directly traceable to Bryce’s three original observations. Despite what his many supporters may claim today, Bryce scored a policy hat trick.

The new standards had an immediate and salutary effect on school facilities. At Marieval Indian Residential School on the Cowessess 73 Reserve in Saskatchewan, lately in the news as a result of the purported discovery of over 700 unmarked graves on its grounds, enrolment was temporarily curtailed in order to comply with the government’s new health rules. “According to the latest requirements of the department as to air space, our school will need to be enlarged to provide sufficient accommodation,” the school reported in 1912. A modern new wing was necessary to bring the school into compliance with regulations.

To meet its obligations arising from the 1911 agreement, the federal government’s budget for Indian education rose sharply from $321,988 in 1907 (see page 975) to $539,145 in 1911 (see page 443). This seems a stunning show of support for the residential school system, particularly given the modest nature of most federal budgets in the early 1900s. Unfortunately, the First World War derailed the department’s ambitious modernization plans and these increases soon disappeared. By 1922, however, Indian Affairs’ budget for Indigenous education was once again on the rise, hitting a record $1,360,000. And by this time, Ottawa had built or remodelled nearly 30 residential schools to the new, healthier standards advocated by Bryce.

A Focus on Reserves

During the ongoing federal-church negotiations, Indian Affairs in 1909 asked Bryce to look more closely at the source and spread of TB among students at residential and day schools. It had been accepted by Bryce and many others that the schools themselves were significant transmitters of the disease. From his 1906 annual report for Indian Affairs (which again expresses opinions about Indigenous society that would be considered scandalous today):

“That the prevalence of tuberculosis amongst the bands is…due directly to infection introduced by one member of a family into a small, often crowded, house, and there, as dried sputum collects on filthy floors and walls, is spread from one to another so certainly and at times so rapidly that one consumptive has in a single winter infected all the members of a household as certainly and rapidly as if he had had small-pox.

That from such houses infected children have been received into schools, notably the boarding and industrial schools, and in the school-room, but especially in the dormitories, frequently over-crowded and ill-ventilated, have been the agents of direct infection.” (Emphasis added.)

In 1909 Bryce and colleague J.D. Lafferty, also a medical doctor, carried out examinations on 243 children at eight native schools in the Calgary area. Their report (see page 253) stated that TB was present in all ages of children they examined, with excessive mortality displayed in pupils between 5 and 10 years old. Crucially, no child awaiting admission to school was found to be free from TB, leading Bryce and Lafferty to the conclusion “that the primary source of infection is in the home” and that “the tuberculized older person in the home is the essential source of the infection.”

A further and equally surprising result was that the age group at greatest risk of mortality, on reserve and off, was infants under the age of 1. As these youngsters had obviously not yet attended any school, the findings strongly suggested the source of TB was in the home.

Bryce and Lafferty’s assertion that family members on reserves, and not church-run, government-funded residential schools, were the true source of TB infections among Indigenous students was reinforced a decade later with the results of the first comprehensive Canadian TB screening study conducted in 1920. This Saskatchewan study employed a newly-invented skin test that could reveal even the dormant stage of TB.

The study sampled a cross-section of the population and found that, even among pre-school non-Indigenous children, 44 percent had TB. Among children at residential and on-reserve day schools, the average infection rate was a stunning 92.5 percent. A further and equally surprising result was that the age group at greatest risk of mortality, on reserve and off, was infants under the age of 1. As these youngsters had obviously not yet attended any school, the findings strongly suggested the source of TB was in the home.

(It should be noted that even today Indigenous Canadians living in remote areas continue to suffer vastly excessive rates of TB. Among non-native Canadians, the current rate is 0.6 per 100,000; among Indigenous Canadians it is 24, and specifically among Inuit 170.)

In the years following his 1909 study, Bryce used his annual reports for Indian Affairs to advocate for a shift in TB programs away from schools and towards reserves. He also continued to promote the idea that assimilation offered the best permanent solution to native health problems. In his 1912 report he again noted that reserves with the lowest rates of TB deaths were those that had integrated the customs of “white people and the unconscious assimilation of the ideas and practices of civilized communities.”

Bryce’s “Other” Recommendations

Bryce continued his regular work at Indian Affairs until 1914, when friction with his boss, the previously mentioned Duncan Campbell Scott, came to a head. According to Bryce’s self-published pamphlet, the reason for this conflict was Scott’s opposition to a set of additional recommendations Bryce had prepared on his own following his 1907 and 1909 reports and that he promoted internally in the department. As he would later explain in his post-retirement version of events, “The recommendations contained in the report were never published and the public knows nothing of them.”

In the current narrative that casts Bryce as heroic whistleblower, Scott has become the moustache-twirling, reform-thwarting villain. Beyond his lengthy career in Indian Affairs, Scott was also an accomplished artist and public intellectual. He was a well-known writer of fiction, plays and poetry, for which he is ranked among the famous “Poets of Confederation.” He also served as president of the Royal Society of Canada and held honorary doctorates from Queen’s University and the University of Toronto.

Today Scott is chiefly remembered as a racist bureaucrat who believed the purpose of the residential school system was to “kill the Indian in the child.” (While commonly attributed to him, this is actually a misquote. Scott did, however, say many comparable things, including that the goal of residential schools was to “get rid of the Indian problem.” What he appears to have meant was that he hoped natives would eventually become fully engaged participants in Canadian society.)

Bryce claims he made repeated remonstrances to Scott demanding that action be taken on his follow-up recommendations. In his own 1910 memo in reply, Scott laid out his objections to Bryce’s plan, arguing they were “impractical” and would shift the focus of residential schools from education to “a sanitorium system.” Co-author Lafferty also disagreed with Bryce. In March 1911, after Bryce felt he had been stonewalled by Scott, he went over his supervisor’s head to plead his case with deputy superintendent Frank Pedley, the highest non-elected official in the department, as well as Pedley’s boss Oliver, the federal Minister of Indian Affairs. From Bryce’s letter to Oliver:

“It is now over 9 months…and I have not received a single communication with reference to carrying out the suggestions of our report. Am I wrong in assuming that the vanity of Mr. D. C. Scott, growing out of his success at manipulating the mental activities of Mr. Pedley, has led him to the fatal deception of supposing that his cleverness will be equal to that of Prospero in calming any storm that may blow up from a Tuberculosis Association or any where else, since he knows that should he fail he has through memoranda on file placed the responsibility on Mr. Pedley and yourself.”

Setting aside the obscure Shakespearean reference, Bryce’s letter clearly put Oliver in a difficult position. He could not accept Bryce’s demands – which clearly imply incompetence on the part of one official and arrogance on another – without undermining his senior staff and the government’s management structure. In many organizations, “going over someone’s head” is a firing offence. In the end, no action was taken on Bryce’s demands. Then in 1913 Pedley resigned amid a departmental scandal and Scott took over as deputy superintendent, where he would remain until 1932.

With his rival Scott now firmly in control of the department, Bryce found himself on the outside. From 1914 to 1921, Bryce remained on the payroll of Indian Affairs, but he no longer wrote the annual health report. It appears he did no work at all for the department. Whatever the reason for this unusual arrangement, Bryce received seven years’ salary for no known effort. While he continued to work for the Department of the Interior, he was silent about residential schools throughout this time.

The Retired Whistleblower

In 1921 Bryce retired in a huff at age 68 after failing to get himself appointed deputy minister of the newly-created federal Department of Health. Clearly upset at how he had been treated, he returned to his concern about health conditions at residential schools. The result was The Story of a National Crime, his self-published 1922 pamphlet now hailed as a significant historical document worthy of centenary celebration.

As his present-day supporters claim, its 20 pages amply detail Bryce’s interest in native health and his opinion on the necessity for action, as well as listing his follow-up recommendations that were overruled by Scott. But anyone who takes the half-hour necessary to read the entire booklet cannot fail to notice that Bryce had other objectives beyond mere munificence.

The inescapable conclusion is that Bryce was a strong and outspoken supporter of compulsory education for all Indigenous students and that he preferred residential schools over convenient on-reserve day schools. These are not popular opinions today.

Nearly a quarter of the document is consumed with Bryce’s complaints about his severance package and what he perceives as shabby treatment by the bureaucracy. “I had a right to aspire…to the position of Deputy Minister of Health,” he grouses. It is, to put it briefly, a self-serving rant. Even Blackstock in her CMAJ hagiography admits that “Bryce’s words do betray a slight self-interest.” As historian John S. Milloy tells it in his book A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System 1879 to 1986, “Much of Bryce’s 1922 narrative is the self-interested tale of his failed ambitions in the Department and of his unsuccessful attempt to secure the appointment as first deputy minister of the Department of Health.”

Of course, many whistleblowers have complicated and overlapping motivations. If we are to judge Bryce on his status as significant source of information regarding government mismanagement or intransigence towards Indigenous issues, then what should really matter are the details, rather than his delivery method. So here, in Bryce’s own words from his 1922 pamphlet, are the recommendations he claims the government ignored to its shame:

- Greater school facilities [for native students], since only 30 per cent of the children of school age were in attendance;

- That boarding schools with farms attached be established near the home reserves of the pupils;

- That the government undertake the complete maintenance and control of the schools…and further it was recommended that as the Indians grow in wealth and intelligence they should pay at least part of the cost from their own funds;

- That the school studies be those of the curricula of the Province in which the schools are situated;

- …That the department provide for the management of the schools, through a Board of Trustees, one appointed from each church…;

- That Continuation schools be arranged for on the school farms…;

- That the health interests of the pupils be guarded by a proper medical inspection and that the local physicians be encouraged through the provision at each school of fresh air methods in the care and treatment of cases of tuberculosis. (Emphasis added.)

The list is at sharp odds with Bryce’s current reputation among Indigenous activists as a truth-telling “hero.” The first and second items would have required a tripling of the number of residential schools in Canada and the closure of most on-reserve day schools where most native children received their education. Although this list does not say so explicitly, it implicitly suggests the imposition of compulsory education long before such a thing was actually established by Scott.

In downplaying the issue of compulsory education, Bryce deliberately or inadvertently manipulated his own legacy by omitting several contentious recommendations from his earlier list that caused him so much grief with Scott. One of these explicitly stated “compulsory schooling should be enforced for Native children” and another called for sweeping reduction in day school operations in favour of greater use of residential schools.

The inescapable conclusion is that Bryce was a strong and outspoken supporter of compulsory education for all Indigenous students and that he preferred residential schools over convenient on-reserve day schools. These are not popular opinions today. Then there is the problematic third recommendation from the 1922 list, suggesting native families be made to pay for the privilege of sending their children to residential schools. Such a thing seems grotesquely humorous, given how Indigenous fans of Bryce such as Palmater routinely characterize the entire residential school system as “genocidal.”

It is uncertain whether Bryce’s recommendation that Ottawa assume complete control over the schools and relegate churches to an oversight role on a proposed national Board of Trustees would have been to the benefit of students. And while his expurgated list contains a few sensible suggestions, most are either unlikely to have made any noticeable difference and/or fall outside the competency of a chief medical officer.

Remember that Bryce had no authority or expertise in areas of funding, curriculum or organizational structure. And, as Scott noted in his 1910 memo, implementing Bryce’s ideas (including those omitted from the 1922 list) would have shifted the schools from educational institutions to health-care-focused operations under the guidance of the chief medical officer, namely Bryce. Beyond giving Bryce control of the entire school system, such a significant policy shift would have required legislative approval since it appeared to violate the federal government’s treaty obligations. All of this likely explains Scott’s refusal to accept Bryce’s follow-up report, regardless of any personal animosity.

Then again, what if Scott had accepted and Ottawa implemented Bryce’s recommendations? Indulging in a bit of counterfactual history, it seems inevitable that Bryce’s reputation today would be experiencing a very different arc. Instead of a brave whistleblower, he would likely be remembered as a deluded bureaucrat who put himself in charge, tripled the number of residential schools, forced all Indigenous kids to attend and then demanded that Indigenous parents pay for the privilege of sending their kids to school off-reserve.

Bryce would thus be regarded as a villain on par with Scott or Macdonald and an accomplice in, if not the architect of, the alleged federal policy of genocide. As such, Bryce would certainly not be receiving transcendental fan mail or the other accolades and attention currently directed his way. That he is widely regarded as a hero today seems the result of the very great stroke of luck that he was ignored in his time. There is considerable irony in recognizing how long-time foil Scott has become responsible for Bryce’s beneficent reputation today.

A Hero for Our Time?

Like all interesting and consequential figures from the past, Bryce was a complicated individual. He was in some ways a pioneer of public health. As chief medical officer for Indian Affairs, Bryce used modern statistical methods to understand and tackle the serious problems of Indigenous health. His 1907 inspection tour revealed disturbing evidence of high mortality rates and poor sanitation practices at the schools and his report brought public attention to bear on the issue. His observations were implemented in full and with reasonable dispatch by the federal government, with positive results.

Two years later, Bryce’s study of Calgary Indigenous students was equally revelatory and established that reserves were the ultimate source of TB infections. His attempts to bring greater attention to native health issues after retirement can be considered further to his credit. He clearly had a passion for Indigenous health at a time when few others did. For all this, Bryce deserves ample recognition today.

But despite the adulation heaped upon him today, Bryce was very much a man of his times. Much of his published work betrays the common prejudices and errors of his era, including the superiority of white culture and the benefits of assimilating natives into white society; many of his compatriots have been discredited and cancelled for similar sins.

If an accommodation can be made for Bryce – if his evil can be “interred with his bones” so that his good may live on – then surely a similar effort can be made for his many cancelled peers as well.

Further, the foundation of Bryce’s reputation as a heroic whistleblower appears misplaced, particularly given the attention paid to his official 1907 report. As for his heralded follow-up recommendations, a close inspection reveals them to be deeply flawed and largely unworkable; and his motivations for revealing them largely self-indulgent. In fact, long-time nemesis Scott appears to have done Bryce’s future reputation an enormous favour by refusing to accept them.

All of which brings us to the great mystery of Bryce’s current elevation to secular sainthood. Contrary to how most of his contemporaries have been treated, Bryce has been excused all his faults so that his other achievements can be celebrated. But surely his many present-day promoters, including academics such as Blackstock and Palmater, have read his 1922 pamphlet and other works and are aware of how discordant and problematic his recommendations, opinions and attitudes seem today.

So why have Bryce’s advocates chosen to celebrate his accomplishments in spite of evidence of his many past mistakes, in sharp contrast to how nearly every other significant character from Canada’s past has been treated in recent years? It is a singular puzzle. Perhaps Bryce’s disparate treatment is meant to offer white Canadians expiation through a single righteous figure. Or maybe it is intended to counter criticism that the popular approach to Canadian history is unrelentingly negative.

Then again, it is possible the chance to invent a narrative of a brave whistleblower attempting to shine a light on the federal government’s habitual disregard for Indigenous health proved so attractive it overwhelmed other concerns about veracity, consistency or principle. Regardless, if an accommodation can be made for Bryce – if his evil can be “interred with his bones” so that his good may live on – then surely a similar effort can be made for his many cancelled peers as well.

By all means, Canadians should reflect on the complex and occasionally inspiring story of Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce and assign credit where due to his achievements and good intentions. But in doing so, we should be prepared to extend that same understanding and indulgence to the rest of Canada’s now-darkened pantheon of historical figures – some of whom are far less compromised than Bryce. Canadians must learn to appreciate their history as it actually happened, regardless of whether that proves narratively or politically convenient.

Greg Piasetzki is a Toronto-based intellectual property lawyer with an interest in Canadian history.