Forgetfulness, and I would even say historical error, are essential in the creation of a nation.

— Ernest Renan, 19th century French historian and philosopher

What part of “Get out!” do Quebec’s English-speakers – aka anglophones, Anglos or les Anglais – not understand? A long succession of governments, separatist and nominally federalist alike, have been sending them a pretty clear message through increasingly repressive language legislation. The latest iteration is Bill 96, which was undergoing public hearings last month, meant to “further strengthen” the language of Molière. As usual, this means weakening English.

Among the Bill’s provisions are a renewed clampdown against English on commercial signs, extending French “certification” requirements to businesses with as few as 25 employees, stripping automatic bilingual status from municipalities whose English population has dropped below 50 percent, and fiddling with the number of students allowed in English colleges (ostensibly to assure a minimum number of spots for English speakers). Even less surprising is the creation of more bureaucracy, including a ministry for language and a “commissioner of the French language.” The latter would transmit language-related complaints directly to the province’s National Assembly. This additional layer of language bureaucracy will cost about $104 million – partly funded by equalization payments from taxpayers in the rest of Canada, of course.

Quebec’s government even had the temerity to insist that Bill 96 will protect English-language rights. When challenged on this subject, Simon Jolin-Barette, the minister responsible for the legislation, retorted that critics may not have read all 100 clauses in the 200-page text, saying that their rights were preserved in “the whole bill” and that verbal assurances he’d given are there “in black and white.” In other words, rest easy Anglos, if you can’t see your rights explicitly etched on a single tree it’s because they’re out in the forest somewhere. The situation can best be summed up by the accompanying vintage cartoon from the Montreal Gazette’s Aislin.

Such “complexities” could well escape the casual observer, while the overall situation might not even seem particularly noteworthy. Quebec is French after all, and whatever they do there is their business. Federal politicians were virtually mute in the months following Bill 96’s introduction in May, no doubt at least partly for fear of electoral consequences in the province. Even the opposition leaders essentially parroted the Prime Minister’s line that “Quebec has a special role to play in protecting French in Quebec.” It never hurts to repeat the province’s name in a sentence. The few critics, such as the Quebec Community Groups Network (an anglophone umbrella organization) and the Conseil du patronat du Québec (concerned about the bill’s impact on small businesses), have been swimming against the nationalist tide.

For students of the province and those who live or have lived there, the new legislation reflects a familiar pattern, the persistent aftershocks of political turmoil close to 60 years old. It’s a reminder that the province’s language wrangles are a not-quite-dead horse that can still be dragged out and flogged repeatedly for political advantage.

The Shadow of Wolfe

The Battle on the Plains of Abraham, fought on September 13, 1759, lasted about one hour. Some 4,400 British troops faced off against 3,400 French and Native allies on open ground outside the walls of Quebec. Contemporary accounts record that after two intense British musket volleys fired at close quarters, the French broke and ran. Both commanders, General James Wolfe and the Marquis de Montcalm, were mortally wounded. While the battle sealed the conquest of New France by Britain, the war has continued – to adapt von Clausewitz’s famous maxim – by different means, in society and politics.

At the Conquest New France was sparsely settled, with perhaps 50,000 inhabitants unevenly dotting a vast landmass. Most lived in the St. Lawrence lowlands along the tributaries of that great waterway, on flat land most suitable for agriculture. English settlement began in earnest after the American Revolution, with about 5,000 United Empire Loyalists – Americans who stuck with Great Britain and fled the nascent United States – settling in the Eastern Townships near the U.S. border, the Gaspéregion and northwest of Montreal.

To these were added an estimated 15,000 Americans who came north in the 1790s, lured by British land grants. These were areas unpopulated by Europeans, often hilly and agriculturally marginal land. Newcomers had to physically carve a life out for themselves, clearing the ancient forests by hand. The common stone fences of the Townships are mute testimony to the physical effort of digging out each rock and carrying, rolling or dragging it to be stacked at the borders of the fields. This, one might argue, constitutes a tie to the land.The pattern of settlement produced areas of predominantly English population, notably the Townships themselves, an area about twice the size of Prince Edward Island.

With the “Revenge of the Cradles,” Quebec’s population explosion in the 19th century, English-settled areas inside and outside Quebec soon saw a large influx of French-speakers. Even so, as late as the First World War, several regions had English majorities, notably parts of the Townships and Gaspé, Huntingdon and Pontiac counties. Even the city of Sherbrooke was still one-third English, while parts of Quebec City were up to 40 percent anglophone early in the last century.

The peak proportion of English speakers in Quebec, 25 percent, had already come and gone, having occurred in the 1840s. Not the 1960s or 70s, when language strife was at its peak, but over 100 years earlier.

Of course, it wasn’t so much the farmers of the Townships or the fishermen of Gaspéwho later drew the ire of Quebec nationalists. It was the reviled merchants of Montreal, the paleo-one-percenters of 19th century Quebec. Many of these businessmen arrived dirt-poor after the Conquest from England, Scotland and Ireland. While most Quebecois maintained their rural occupations, a small number of these immigrants, for better or worse, built the economy of Quebec and later the new country of Canada.

The fur trade, through the legendary Hudson’s Bay and upstart Northwest companies, brought the first torrent of wealth into Quebec. On that foundation was built the financial heart of Canada, St. James Street in Old Montreal. Montreal bankers financed the mills, mines and railways – most notably the CPR – that formed the base of the new country’s economy. Some of the associated imposing architecture still stands: the neo-classical Bank of Montreal building (1847) and art deco Aldred Building (1931) in the old financial district, the Sun Life Building on Dominion Square in Montreal – the largest building in the Commonwealth when constructed in 1931 – and Price House (1931) towering over the upper town in Quebec City. If the stones of these structures could speak, they’d just as likely speak English or even Gaelic as French.

All this said, the peak proportion of English speakers in Quebec, 25 percent, had already come and gone, having occurred in the 1840s. Not the 1960s or 70s, when language strife was at its peak, but over 100 years earlier. Even so, the pattern of cultural symbolism and political narratives set in the 19th century has proven extremely durable.

Spinning Resentment into Revolution

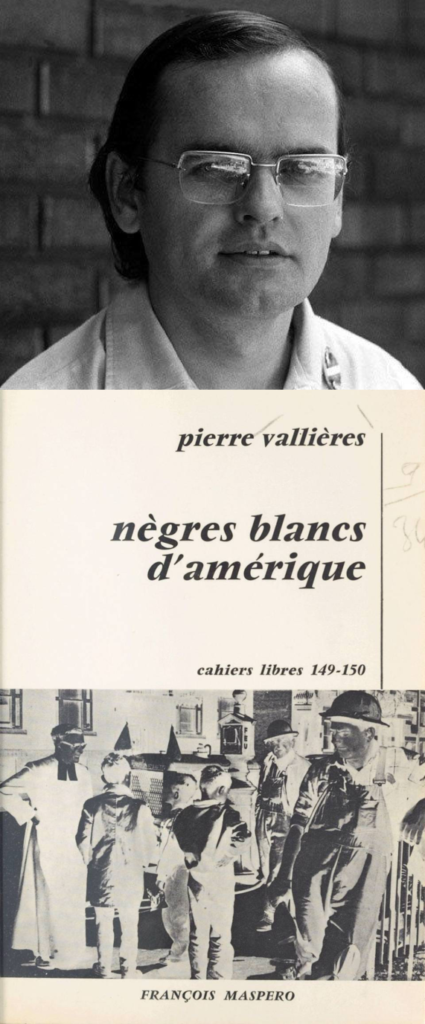

When writing his memoir and magnum opus, Nègres blancs d’Amérique, the Quebecois Marxist Pierre Vallières could not have known it would lead – indirectly and decades later – to the firing of Wendy Mesley. Perhaps he’d be smugly satisfied to know the veteran TV journalist and program host uttered the English title of his book in a staff meeting, only to be denounced and disciplined by the CBC. She retired this year.

Written in 1966, Nègres blancs captured the revolutionary Zeitgeist. It cast the lot of the Quebecois into by-now familiar terms – an oppressed group colonized by Anglo-American capitalists and requiring liberation via Marxist revolution. Anticipating today’s post-modern orthodoxy, Vallières further analyzed Quebec society on the basis of entrenched “power dynamics.” No less an authority than the then-unassailable New York Times placed the book alongside the writings of Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon and Che Guevara.

Linguistic and cultural animosity was now seen through a Marxist, oppressor-victim lens, and this narrative was increasingly accepted by violent revolutionaries and the political class alike. Terrorists of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) had been detonating bombs around Quebec since 1963, including an attack on the Montreal Stock Exchange – symbol of both capitalist and Anglo oppression – resulting in several deaths. Their campaign culminated in the kidnappings of the 1970 October Crisis and murder of provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte. Various separatist parties formed: the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale, the Ralliement National and Réné Lévesque’s Mouvement Souvraineté-Association – the latter two combining to form the Parti Québécois.

It’s fair to ask whether the “oppression” of French Quebeckers could realistically be shoehorned into a Marxist narrative and whether the violent upheavals were proportionate to the alleged historical injustices.

As with many divisive social movements, there was a kernel of truth in the overflowing feedbag of nativist grievances. The Anglo financial elite was no figment of their imagination. Denizens of Montreal’s Golden Square Mile, the collection of mansions at the foot of Mt. Royal, controlled most of Canada’s money. Some, like Sir Herbert Holt, the early 20th century’s richest Canadian, were as personally unsympathetic – reportedly boasting of his own business acumen during the Great Depression – as they were financially successful. Montrealers needed Holt’s electricity, gas and coal for light, cooking and heat at home; his trams to get to work; and his cigarettes, newspapers and theatres for what little free time remained.

Despite the conspicuous wealth of the few, the vast majority of Anglos were not bankers, industrialists or railway owners. They were common people, ‘colonials’ like their French neighbours, sharing the same hardships, modest lifestyles and generally limited horizons.

The 19th century was also the height of British imperialism, and its mores dominated much of the globe, not just Quebec. Unsurprisingly, the province’s cities had an outsized English flavour up to the First World War, even in Quebec City, and later still in Sherbrooke and Montreal. French residents often had to learn English just to get by, and in some Anglo-owned or -run organizations, it was reportedly forbidden for the workers to speak French.

And did some lower-class Anglos, basking in the reflected grandeur of the magnates and limited by unilingual Britishness, look down their noses at the French? Undoubtedly. To this day Quebecois families recount stories of some relative or other denied service in French somewhere, typically at Montreal’s iconic Eaton’s department store. While such real or apocryphal slights long fed the narrative of historical grievances, it’s hard to see why an ancestor’s bad retail experiences should cloud current social or political debate. But so they have.

On the other side of the ledger, the religion (and thereby education) and property rights of the Quebecois were guaranteed by the British Crown from 1774, 11 years after the Conquest. The Quebecois became politically active early on and soon had a stranglehold on provincial politics. In the Province of Canada, a rough amalgam of Quebec and Ontario from 1841 to Confederation, all but three of the Premiers of Canada East (Quebec) were French-speakers, the English premiers collectively serving less than two years. Since Confederation, four of Quebec’s 32 Premiers have had English surnames but they were all arguably francophones, together serving less than five years. And of course, the Quebecois have (in some cases literally) punched above their weight in Canadian politics, with their native sons serving as Prime Minister for 62 of the 121 years since 1900.

Despite the conspicuous wealth of the few, the vast majority of Anglos were not bankers, industrialists or railway owners. They were common people, “colonials” like their French neighbours, sharing the same hardships, modest lifestyles and generally limited horizons. There were disparities between English and French workers early on, but these had largely disappeared by the time of the 60s nationalist explosion.

As a percentage of Quebec’s total workforce in 1931, clerical, professional and managerial employees comprised 30 percent English and 12 percent French speakers. Fifty years later the figures were 40 percent and 29 percent, respectively. Similarly, in 1961 the average French male Montrealer made only 66 percent of his English counterpart’s wages or salary level; by 1980 – the year of the first separation referendum – he was making 88 percent as much.Behind these relative improvements for Quebecois workers lie complex changes in the types of work done, education and other factors, as French speakers were entering different parts of the economy. Similar strides were being made in the cultural realm, like French CBC radio and television.

Regardless, the much-coveted “C-suites,” as they’re known today, were an ongoing obsession for nationalists, and average Anglos became collateral damage. Starting during the Second World War, a key political initiative was the creation of the provincially-owned Hydro Quebec. This was accomplished entirely by expropriating private utilities, including assets once owned by the much-maligned Herbert Holt. These private companies were targeted due to their “inefficiency,” but it can be no coincidence that many of the owners and executives were Anglos. The last phase of this effort in the early 60s was led by Lévesque, then a Liberal cabinet minister.

As government had long been the domain of the francophone majority, the bureaucracy was already monolithically French. By the 70s non-French bureaucrats represented barely 1 percent of the total despite English-speakers still making up about 20 percent of Quebec’s population (reference available in print only; see page 16), and that hasn’t changed. The ratio now hovers around 0.9 percent. By contrast, Ontario Francophones are 4 percent of that province’s population but make up 8 percent of the provincial civil service. And while 20.6 percent of Canadians are French-speaking, over 26 percent of federal bureaucrats are francophones. Some years ago, when challenged with such numbers, a Parti Québécois minister – displaying singular self-awareness – remarked, “We really have no lessons to learn from the rest of Canada about welcoming or integrating people.”

With government well in hand and the private sector in its crosshairs, the province turned its attention to education and language policy. For students of this onslaught, the numbers of the various bills just roll off the tongue: 63, 22, 101, 178 and now 96. The first was introduced by Union Nationale education minister Jean-Guy Cardinal in 1969, to limit immigrant children’s access to an English education. Liberal Premier Robert Bourassa tried to forestall the nationalist tide with 1974’s Bill 22, making Quebec unilingual and French alone the language of government and the workplace (even as Canada was extending official bilingualism).

The election of the separatist Parti Québécois in 1976 brought the expansive Bill 101 three years later, majestically called “The Charter of the French Language,” It still casts a dark shadow over provincial politics today. The sweeping legislation was intended to “make French the language of government and law, as well as the normal and everyday language of work, instruction, communication, commerce and business.” The bill created “rights” in areas normally governed by the spontaneous interactions of civil society, namely:

(Article 3) The right of workers to carry on their activities in French,

(Article 4) The right of consumers to be informed and served in French.

Respectively, these could be termed the “Maudit Anglais foreman” and “Eaton’s saleslady” articles, meant to redress the longstanding, often very personal, resentments discussed above.

Aspects of the “Charter” were subjected to constitutional challenges, prompting minor modification by another Bourassa government through Bill 178 in 1988. Quebec’s language policy became a chimeric blend of Robespierre and Inspector Clouseau, plaguing the province’s minorities forevermore. Outsiders certainly found it bewildering, if not maddening.

Its authoritarianism became legion. One implementing organ was the Commission de Toponomie, which began practising on-the-ground historical revisionism, renaming (to French) geographic landmarks and places. Access to pre-university public education in English was severely restricted. Initially, children needed one parent to have been educated in a Quebec English school to be eligible (but, because this conflicted with Canada’s Constitution, it was watered down to an English-educated parent from anywhere in Canada). Consequently, many Quebec politicians (including separatists) sought out private schools, where their children could learn English just fine.

But above all, Bill 101 empowered the Office de la Langue Francaise, which became legendary (or infamous) as the “language police,” to enforce the law’s myriad provisions. This released the inner pencil-neck in many minor bureaucrats, who spanned the province with (literal) tape measures checking font sizes on signs, masqueraded as retail customers to test for “appropriate greetings,” and manned snitch lines to which the most linguistically-vexed citizens called in complaints on their unwitting neighbours.

A burning public policy question has enflamed Quebec for years, namely the use of the phrase ‘Bonjour/Hi.’ Debate has raged over banning this greeting from businesses and government offices. The Parti Québécois proposed a requirement that all customers, everywhere, be greeted only with a ‘warm bonjour.’

The current Bill 96 augments Bill 101 by unilaterally modifying the Canadian Constitution to declare Quebec a “nation,” and applying provincial language restrictions to federally-regulated private-sector workplaces (such as banks), covering an additional 135,000 Quebec workers that Bill 101 had not ensnared. Given that the Constitution isn’t changed every day, the reaction of federal politicians, or lack thereof, might concern some. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau went so far as to affirm Quebec’s right to edit the document, saying, “It is perfectly legitimate for a province to modify the section of the Constitution that applies specifically to them. (sic)” He further observed that Quebec’s unilingual status had “already been recognized.” In other words, if there could be anything less than a nothingburger, this would be it.

“Bonjour/Hi”

In 1960s Montreal there was a shop called International Fruit on St. Lawrence Blvd. near Pine Ave. The story goes that the owners were three men who didn’t much like each other, brought together by marrying a trio of sisters. The small space was typically jammed with hordes of immigrants jostling for the best produce. Other than the quality and selection, what made the store unique were the three corpulent men behind the counter. They would assiduously observe each group of customers in line and, as you came to the cash, greet you in whatever language they’d heard you speaking. “Is that all you’re getting?” “Find everything?” How old is the boy?” or similar questions would be asked in Magyar, Polish, German or Yiddish. No problem.

This is useful context for a burning public policy question that has enflamed Quebec for years, namely the use of the phrase “Bonjour/Hi.” Debate has raged over banning this greeting from businesses and government offices. The Parti Québécois proposed a requirement that all customers, everywhere, be greeted only with a “warm bonjour.” In response, the government promised to tackle the offending phrase, specifically the bit on the right side of the diagonal, citing concerning statistics from the provincial language police. Apparently, French-language greetings in Montreal “dropped from 84 to 75 percent between 2010 and 2017.” Shocking. Clearly, the days of International Fruit are long gone.

Quebec language policy is fuelled by the aforementioned personal and historical anxieties. Quebecois cultural extinction is a recurring theme, despite all evidence to the contrary. As recently as the 2018 election, Premier François Legault said that he “feared that his grandchildren would no longer speak French.” Quebec must be one of the few jurisdictions where demography is a solid career choice for new grads. Not a year goes by without a forensic analysis of linguistic numbers, particularly in the boroughs of Montreal. If a few hundred Anglos move from one suburb to another, headlines scream “Anglais en augmentant!” – English Increasing!

As Canada’s principal metropolis up to about 1970, with roughly 40 percent of its population not-native-French speakers, Montreal was and remains the main point of friction. Over the years, many Quebecois arriving from uniformly French regions must have been shocked to encounter so many unilingual anglophones, or Hassidic Jews for that matter. But the city’s organic development need not have symbolized a demographic time bomb. While the Montreal region is still about 40 percent non-French today, English in the rest of the province has been more or less extinguished. So the idea that “perdre la metropole” – losing Montreal – is either likely or, even if it happened, would cause some kind of demographic domino effect, is simply wrong. There is no way Sherbrooke will become majority English as it was 200 years ago.

That said, something about Montreal’s complexity just sticks in the craw of Quebec’s nationalists. Bill 101 mandated unilingual French signs to maintain the “French face” of the province. This deliberately hid the faces of Montreal’s remaining 40 percent. Years before “Bonjour/Hi,” the word “STOP” was removed from street corners, leaving “ARRÊT” (even though France itself uses “STOP”). Throughout the 60s and 70s, “STOP” signs were frequently spray-painted by nationalist vandals.

Montreal’s also been known for language segregation by neighbourhood or borough. Consequently, an itinerant French-speaker stumbling into an 80 percent English neighbourhood – or Chinatown – might be greeted in English. Not an obvious tragedy. These trivial everyday occurrences are apparently so offensive, however, that they must be extinguished by legislation and the “right” to a French greeting enforced.

“Bonjour/Hi” is actually a very humane compromise. Prior to its appearance, meeting a Montreal shopkeeper or cashier would often initiate a bizarre, hurried profiling dance to choose the appropriate greeting based on the neighbourhood or the customer’s appearance. Drab tweed = English; faux leopard-skin (perhaps accented with fur-topped white booties) = French. But why would French speakers be offended by “Hi” in the first place? Is it a distasteful reminder that there are non-French people around, an insult to “the nation,” the thin edge of the assimilationist wedge?

Such hypersensitivity and endless suspicion rightly astound English Canadians and reasonable people in general. But they are all-too familiar to immigrants from Eastern Europe or other areas of ethnic strife. In some important respects, modern Quebec is closer to 19th century Budapest than 21st century Western Europe or America. Historical grievances, many mythical and some demonstrably absurd, are taught in schools and preserved, to be dusted off for political use. For example, there is widespread belief in the “fact” that Quebec is a net contributor to Canada’s finances.

Another “subtle” Quebec cultural habit is to subject politicians to genealogical scrutiny so purists might sniff out the submerged influence of non-French ancestors. Pierre Elliott Trudeau was accused by nationalists of being “more Elliott than Trudeau,” and the Parti Québécois attempted to embarrass former Premier Jean Charest because he was baptised “John” rather than “Jean.” Charest weakly blamed an “Irish priest” for the error.

Had Rousseau delivered the identical remarks about English in, say, Zurich, his Swiss audience would have smiled and nodded appreciatively at the Canadian CEO’s compliment of their cosmopolitanism. In at least one way, Quebec will always remain a province.

No Quebecois, certainly none of prominence, ridicules these arcane attitudes and policies. Some astute observers, like Conrad Black, are angered that Quebec’s political class didn’t live up to the bargain implied by a bilingual Canada. But this is not what ethnic nationalists do. Quebec politicians and intellectuals had a choice as they asserted power from the 1950s onward. They could have employed some kind of collective Golden Rule, treating their minorities as they would themselves like to be treated. Instead they went for a good old-fashioned settling of scores as practised by ethnic nationalists everywhere.

Freed from the “English yoke,” they’d now give them some of their own medicine. Rather than promoting the common courtesy of learning the majority language, they legislated it and continue to do so. The retailer wouldn’t be left to figure out that serving Montreal’s francophone majority in their own language was simply good business, they’d be damned well fined into doing so.

Events seem to keep stoking Quebec’s linguistic dumpster fire, as with the recent imbroglio over Air Canada’s new president and CEO. Michael Rousseau had worked in Montreal for 14 years and recently stated that he was always able manage just fine without learning French. The revelation came in response to media questions after Rousseau’s maiden speech as Air Canada president to the Montreal Board of Trade – given almost entirely in English. Predictably, the merde hit the ventilateur.

Despite Rousseau’s attempted apology, tempers were still inflamed two weeks after the speech. Protesters demonstrated outside an Air Canada board meeting while Jean-Paul Perreault, president of Impératif français, called for mass resignations including “the entire board of Air Canada…the ministers of transport and official languages and the official languages commissioner.” The Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland also piled on, the former remarking that this was an “unacceptable situation” while the latter boldly instructed the national carrier to have “significant improvement” in Rousseau’s language facility “incorporated as one of his key performance goals.” Ouch. No matter that the Ontario-educated Rousseau had been named Canada’s CFO of the year in 2017.

Also no matter that had Rousseau delivered the identical remarks about English in, say, Zurich, his Swiss audience would have smiled and nodded appreciatively at the Canadian CEO’s compliment of their cosmopolitanism. In at least one way, Quebec will always remain a province. For many Quebecois it’s just more stupidity and tone-deafness from an Anglo executive, another insult to the entire province, Sir Herbert Holt all over again. But worse for some nationalists: couldn’t Rousseau, a native of Cornwall, Ontario, be that assimilated grandchild they all fear having? A harbinger of the dreaded demographic disaster?

Average Anglos enduring Quebec’s unending ethno-social catharsis are viewed the same way. The minimum wage saleswoman at Eaton’s was not just personally limited, or discourteous; she is an eternal symbol, a cog in the great machine oppressing Quebec. Even today, each individual Anglo could become a surrogate for the haughty landlord or manager of decades past.

As with minorities everywhere, they serve a dual purpose. They are obstacles on the shining path to the monocultural utopia, but also politically useful in rallying voters to the nationalist banner. The myths of the Quebec historical narrative are just too glorious not to be true. For separatists in particular, the one solution for much or all that ails the province – independence and unilingualism – is simple and neat. We know where the minorities sit in that equation.

Sorely Missed: One Pit Bill

In light of the linguistic and cultural vise applied to Quebec’s Anglophones since the 60s, it is remarkable how little resistance was offered by the minority, especially its leaders. One notable exception was William (Bill) Johnson, a respected journalist, author of several books and member of the Order of Canada. As president of Alliance Quebec, the province’s federally designated representative of anglophones, Johnson became an impassioned defender of English-speakers’ constitutional rights and sharp critic of the nationalist drumbeat.

Johnson was dubbed “Pit Bill” and vilified by Quebec nationalists and establishment Anglos alike, ostensibly for his confrontational style. In reality, Johnson was usually soft-spoken and highly personable; what actually enraged his critics was his habit of truthfully exposing the hypocrisy and illegality of nationalist policies. He became a one-man myth-buster, elegantly explaining how the nationalist narrative was based on slanted history wherein the anglophone was a convenient scapegoat, continuously trotted out to account for Quebec’s problems.

Conspicuous by their absence as defenders of minority rights were the scions of the Anglo establishment. By contrast, prominent Jewish Montrealers like acerbic novelist Mordecai Richler and filmmaker William Weintraub stepped up. The former drew nationalist ire for ridiculing the absurdities of the ever-expanding language restrictions, while the latter documented the achievements and decline of English Montreal. One can’t help but see the irony of these men, whose families likely fled persecution in Europe only to again be targeted in Quebec. Johnson passed away in 2020, having stepped away from Alliance Quebec in 2000. The organization folded in 2005, leaving a further leadership void amongst Quebec’s minorities.

Something that might have moderated the nationalist tide was one credible nationalist voice speaking up and calling foul on the stupidity and excesses. Of course, Trudeau and Charest didn’t count because they were genetically compromised. As it turned out, the entire Quebec political class, the cultural and intellectual elites – down to the last man and woman – were with the program. So universal is this creed that one simply can’t imagine a pure laine Quebecois questioning Vallière’s myth or, heaven forbid, lauding the contribution of English speakers, from clearing the wilderness to setting the foundations of Quebec’s economy.

The nationalist figure once touted as a linguistic “moderate” was Réné Lévesque. But while speaking to students at Scarborough College in 1968, Lévesque’s real views surfaced. This happened shortly after he formed the first movement advocating “sovereignty-association” with Canada (a form of soft separatism). When asked how the English minority would be treated in a hypothetically independent Quebec, he replied, “better than ‘our’ minorities have been treated elsewhere.” This was an allusion to French minorities outside Quebec being subject to provincial laws (beginning in the 1890s) restricting French in education and civil life.

But by the time Lévesque made these remarks, substantial reforms to these inequities were either completed or underway at the federal level and in many provinces. In fact, the late 60s marked a major point of divergence: French rights and services outside Quebec progressively improved while those of anglophones in Quebec diminished. This is what Conservative MP Scott Reid termed asymmetrical bilingualism, discussed in this C2C Journal article.

Most striking in Lévesque’s remarks was his seething resentment of what he called Quebec’s “privileged minority,” the “money group” in Montreal. His voice reached an angry crescendo in recounting a meeting with what could be called Ur-Laurentians, apparently including the grandson of a former Lieutenant General and the nephew of “Mr. McLaughlin,” then president of the Royal Bank. Incensed at the arrogance of “the money elite,” Lévesque suggested “the quicker they leave the better.”

Lévesque often called such people “Westmount Rhodesians,” a reference to the tiny white population that at the time still ran and essentially owned the future Zimbabwe. Lévesque frequently used this slur against the English business elite to bolster the colonial oppression myth, oppression that could only be solved through “liberation” from Canada.

Ultimately, the Anglo elite did follow their money down Hwy. 401, as Levesque hoped they would. In fact, the Anglo establishment largely swallowed the Westmount Rhodesians calumny, thereby test-driving the cultural capitulation that has increasingly characterized the Laurentian Elite.

Even that profound “victory” did not cool nationalist resentment, however, which was ultimately visited upon remaining English Quebeckers. During the rollout of Bill 101, Lévesque himself met occasionally with minority communities. One public meeting was at MacDonald-Cartier High School in the Montreal suburb of St. Hubert, where school board member Jim O’Donnell rose to ask the Premier a question. O’Donnell was a tall, barrel-chested Irish-Quebecker with hands like vintage baseball mitts. He’d been a Liberal organizer during the era of Maurice Duplessis, when Lévesque was still a Liberal, and had had bloody run-ins with Union Nationale thugs. This evening, O’Donnell’s question to Lévesque was simple: despite the unprecedented objectives of the language charter, couldn’t we just live and let live, get along the way we always had? Lévesque flashed his sardonic half smile, cigarette hanging in one corner of his mouth, shrugged and, in a rambling answer, said “No.” These changes were for real and forever.

Faith in the Liberals, the go-to party for Anglos since Trudeau the elder, has been repeatedly dashed. Quebec’s minorities have been thrown under the bus in search of Francophone votes, the vehicle occasionally circling around to run over them again, as with Justin Trudeau’s support of Bill 96.

In facing Quebecois nationalism and the assault on their rights, Quebec’s Anglos failed in two essential areas. Many – particularly community leaders – passively absorbed the oppressor-oppressed narrative advanced by radicals such as Vallières and accepted by francophone federalists and separatists alike. This acquiescence in their own delegitimization sapped their ability to stand up for English historical and cultural rights. Second, they fatally underestimated the inexhaustible power of nationalism itself to propel some Quebecois relentlessly toward a chimerical ethnic utopia, an Odyssey wherein any opposition could be justifiably crushed.

“Va-t’en/Bye-Bye”

There are many legends passed amongst English Quebeckers and the Anglo diaspora – the hundreds of thousands who’ve gone down the road since the 60s (by 2016, anglophones were down to less than 7.5 percent of Quebec’s population). Most have to do with hockey – which Stanley Cup team, from which decade, was really the best? – Montreal comfort food or the endless summer of Expo ’67.

One has to do with the Five Roses Flour sign in Montreal’s harbour. For decades, the giant red neon sign stood atop the tall brick building in the lower town, alternately flashing the words “FARINE” and “FLOUR.” That is until Bill 101, when “flour” was removed. The legend is that there is a large secret warehouse – unknown to the Office de la Langue Française – where the five two-storey-high letters are hidden. These, along with the thousands of illegal apostrophes removed from commercial signs, will be brought out and restored, one day, when the universe regains its balance and linguistic sanity returns.

Far more likely, unfortunately, is that Quebec politics and history will perpetuate the oppression myth and exaggerated demographic angst. There will always be political gain in “strengthening” French and strangling English.

Canadian realpolitik dictates that no federal party defend Quebec’s minorities. Faith in the Liberals, the go-to party for Anglos since Trudeau the elder, has been repeatedly dashed. Quebec’s minorities have been thrown under the bus in search of Francophone votes, the vehicle occasionally circling around to run over them again, as with Justin Trudeau’s support of Bill 96.

And Quebec’s “distinctiveness” is displayed in so many ways beyond language. They invent ever-more rights, including a veto over goods transiting the province. During the recent federal election, Premier Legault issued his “list of demands,” the message being, regardless of who wins, this is the minimum. Such behaviour will continue due to the raw calculus of electoral math as long as Quebec seats are needed for victory in federal elections. Even the effects of redistribution on the House of Commons due to westward-shifting population will be fought by Quebec, as with Legault’s recent agitation against the loss of a single Quebec seat.

The prospects for Quebec’s minorities are clear. Whether or not Quebec bans “Bonjour/Hi,” the message to Anglos is “Va-t’en/Bye-bye.”

John Weissenberger is a Calgary geologist, originally from Montreal, who speaks English, French and German.

Source of main image: The Canadian Press/Graham Hughes.